Social:Tajik language

| Tajik | |

|---|---|

| Tajiki Persian | |

| Тоҷикӣ (Tojikī, تاجيکى), форсии тоҷикӣ (Forsii Tojikī, فارسى تاجيکى) | |

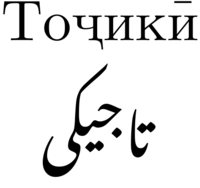

"Tojikī" written in Cyrillic script and Perso-Arabic script (Nastaʿlīq calligraphy) | |

| Native to | Tajikistan Uzbekistan |

| Region | Central Asia |

| Ethnicity | Tajiks |

Native speakers | 10.5 million (2022–2023)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Dialects |

|

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Rudaki Institute of Language and Literature |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | tg |

| ISO 639-1 | tgk |

| ISO 639-3 | tgk |

| Glottolog | taji1245[2] |

| Linguasphere | 58-AAC-ci |

Areas where Tajik speakers comprise a majority shown in dark purple, and areas where Tajik speakers comprise a sizeable minority shown in light purple[citation needed] | |

Template:Tajiks Tajik,[3][lower-alpha 1] Tajik Persian, Tajiki Persian,[lower-alpha 2] also called Tajiki, is the variety of Persian spoken in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan by ethnic Tajiks. It is closely related to neighbouring Dari of Afghanistan with which it forms a continuum of mutually intelligible varieties of the Persian language. Several scholars consider Tajik as a dialectal variety of Persian rather than a language on its own.[4][5][6] The issue of whether Tajik and Persian are to be considered two dialects of a single language or two discrete languages[7] has political aspects to it.[8]

By way of Early New Persian, Tajik, like Iranian Persian and Dari Persian, is a continuation of Middle Persian, the official administrative, religious and literary language of the Sasanian Empire (224–651 CE), itself a continuation of Old Persian, the language of the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC).[9][10][11][12]

Tajiki is one of the two official languages of Tajikistan, the other being Russian[13][14] as the official interethnic language. In Afghanistan, this language is less influenced by Turkic languages and is regarded as a form of Dari, which has co-official language status.[15] The Tajiki Persian of Tajikistan has diverged from Persian as spoken in Afghanistan and even more from that of Iran due to political borders, geographical isolation, the standardisation process and the influence of Russian and neighbouring Turkic languages. The standard language is based on the northwestern dialects of Tajik (region of the old major city of Samarqand), which have been somewhat influenced by the neighbouring Uzbek language as a result of geographical proximity. Tajik also retains numerous archaic elements in its vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammar that have been lost elsewhere in the Persophone world, in part due to its relative isolation in the mountains of Central Asia.

Name

Up to and including the nineteenth century, speakers in Afghanistan and Central Asia had no separate name for the language and simply regarded themselves as speaking Farsi, which is the endonym for the Persian language. The term Tajik derives from Persian, although it has been adopted by the speakers themselves.[16] For most of the 20th century, its name was rendered in the Russian spelling of Tadzhik.[17]

In 1989, with the growth in Tajik nationalism, a law was enacted declaring Tajik the state (national) language, with Russian being the official language (as throughout the Union).[18] In addition, the law officially equated Tajik with Persian, placing the word Farsi (the endonym for the Persian language) after Tajik. The law also called for a gradual reintroduction of the Perso-Arabic alphabet.[19][20][21]

In 1999, the word Farsi was removed from the state language law.[22]

Geographical distribution

Two major cities of Central Asia, Samarkand and Bukhara, are in present-day Uzbekistan, but are defined by a prominent native usage of Tajik language.[23] [24] Today, virtually all Tajik speakers in Bukhara are bilingual in Tajik and Uzbek. This Tajik–Uzbek bilingualism has had a strong influence on the phonology, morphology, and syntax of Bukharan Tajik.[25]

Tajiks are also found in large numbers in the Surxondaryo Region in the south and along Uzbekistan's eastern border with Tajikistan. Tajiki is still spoken by the majority of the population in Samarkand and Bukhara today although, as Richard Foltz has noted, their spoken dialects diverge considerably from the standard literary language and most cannot read it.[26]

Official statistics in Uzbekistan state that the Tajik community comprises 5% of the nation's total population.[27] However, these numbers do not include ethnic Tajiks who, for a variety of reasons, choose to identify themselves as Uzbeks in population census forms.[28]

During the Soviet "Uzbekisation" supervised by Sharof Rashidov, the head of the Uzbek Communist Party, Tajiks had to choose either to stay in Uzbekistan and get registered as Uzbek in their passports or leave the republic for the less-developed agricultural and mountainous Tajikistan.[29] The "Uzbekisation" movement ended in 1924.[30]

In Tajikistan Tajiks constitute 80% of the population and the language dominates in most parts of the country. Some Tajiks in Gorno-Badakhshan in southeastern Tajikistan, where the Pamir languages are the native languages of most residents, are bilingual. Tajiks are the dominant ethnic group in Northern Afghanistan as well and are also the majority group in scattered pockets elsewhere in the country, particularly urban areas such as Kabul, Mazar-i-Sharif, Kunduz, Ghazni, and Herat. Tajiks constitute between 25% and 35% of the total population of the country. In Afghanistan, the dialects spoken by ethnic Tajiks are written using the Persian alphabet and referred to as Dari, along with the dialects of other groups in Afghanistan such as the Hazaragi and Aimaq dialects. Approximately 48%-58% of Afghan citizens are native speakers of Dari.[31] A large Tajik-speaking diaspora exists due to the instability that has plagued Central Asia in recent years, with significant numbers of Tajiks found in Russia, Kazakhstan, and beyond. This Tajik diaspora is also the result of the poor state of the economy of Tajikistan and each year approximately one million men leave Tajikistan to gain employment in Russia.[32]

Dialects

Tajik dialects can be approximately split into the following groups:

- Northern dialects (Northern Tajikistan, Bukhara, Samarkand, Kyrgyzstan, and the Varzob valley region of Dushanbe).[33]

- Central dialects (dialects of the upper Zarafshan Valley)[33]

- Southern dialects (South and East of Dushanbe, Kulob, and the Rasht region of Tajikistan)[33]

- Southeastern dialects (dialects of the Darvoz region and the Amu Darya near Rushon)[33]

The dialect used by the Bukharan Jews of Central Asia is known as the Bukhori dialect and belongs to the northern dialect grouping. It is chiefly distinguished by the inclusion of Hebrew terms, principally religious vocabulary, and historical use of the Hebrew alphabet. Despite these differences, Bukhori is readily intelligible to other Tajik speakers, particularly speakers of northern dialects.

A very important moment in the development of the contemporary Tajik, especially of the spoken language, is the tendency in changing its dialectal orientation. The dialects of Northern Tajikistan were the foundation of the prevalent standard Tajik, while the Southern dialects did not enjoy either popularity or prestige. Now all politicians and public officials make their speeches in the Kulob dialect, which is also used in broadcasting.[34]

Phonology

Vowels

The table below lists the six vowel phonemes in standard, literary Tajik. Letters from the Tajik Cyrillic alphabet are given first, followed by IPA transcription. Local dialects frequently have more than the six seen below.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | и ӣ /i/ | у /u/ | |

| Mid | е /e̞/ | ӯ /ɵ̞/ (/o̞/) | |

| Open | а /a/ | о /ɔ/ | |

In northern and Uzbek dialects, classical /o̞/ has shifted forward in the mouth to /ɵ̞/. In central and southern dialects, classical /o̞/ has shifted upward and merged into /u/.[36] In the Zarafshon dialect, earlier /u/ has shifted to /y/ or /ʊ/, however /u/ from earlier /ɵ/ remained (possibly due to influence from Yaghnobi).[37]

The open back vowel has varyingly been described as mid-back [o̞],[38][39] [ɒ],[40] [ɔ][8] and [ɔː].[41] It is analogous to standard Persian â (long a). However, it is standardly not a back vowel.[42]

The vowel ⟨Ӣ ӣ⟩ usually represents a stressed /i/ at the end of a word. However, not all instances of ⟨Ӣ ӣ⟩ are stressed, as can be seen with the second person singular suffix -ӣ remaining unstressed.

The vowels /i/, /u/ and /a/ may be reduced to [ə] in unstressed syllables.

Consonants

The Tajik language contains 24 consonants, 16 of which form contrastive pairs by voicing: [б/п] [в/ф] [д/т] [з/с] [ж/ш] [ҷ/ч] [г/к] [ғ/х].[35] The table below lists the consonant phonemes in standard, literary Tajik. Letters from the Tajik Cyrillic alphabet are given first, followed by IPA transcription.

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post-alv./ Palatal |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | м /m/ | н /n/ | |||||

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | п /p/ | т /t/ | ч /tʃ/ | к /k/ | қ /q/ | ъ /ʔ/ |

| voiced | б /b/ | д /d/ | ҷ /dʒ/ | г /ɡ/ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | ф /f/ | с /s/ | ш /ʃ/ | х /χ/ | ҳ /h/ | |

| voiced | в /v/ | з /z/ | ж /ʒ/ | ғ /ʁ/ | |||

| Approximant | л /l/ | й /j/ | |||||

| Trill | р /r/ | ||||||

At least in the dialect of Bukhara, ⟨Ч ч⟩ and ⟨Ҷ ҷ⟩ are pronounced /tɕ/ and /dʑ/ respectively, with ⟨Ш ш⟩ and ⟨Ж ж⟩ also being /ɕ/ and /ʑ/.[43]

Word stress

Word stress generally falls on the first syllable in finite verb forms and on the last syllable in nouns and noun-like words.[35] Examples of where stress does not fall on the last syllable are adverbs like: бале (bale, meaning "yes") and зеро (zero, meaning "because"). Stress also does not fall on enclitics, nor on the marker of the direct object.

Grammar

The word order of Tajiki Persian is subject–object–verb. Tajik Persian grammar is similar to the classical Persian grammar (and the grammar of modern varieties such as Iranian Persian).[44] The most notable difference between classical Persian grammar and Tajik Persian grammar is the construction of the present progressive tense in each language. In Tajik, the present progressive form consists of a present progressive participle, from the verb истодан, istodan, 'to stand' and a cliticised form of the verb -acт, -ast, 'to be'.[8]

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

In Iranian Persian, the present progressive form consists of the verb دار, dār, 'to have' followed by a conjugated verb in either the simple present tense, the habitual past tense or the habitual past perfect tense.[45]

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

Nouns

Nouns are not marked for grammatical gender, although they are marked for number.

Two forms of grammatical number exist in Tajik, singular and plural. The plural is marked by either the suffix -ҳо -ho or -он -on (with contextual variants -ён -yon and -гон -gon), although Arabic loan words may use Arabic forms. There is no definite article, but the indefinite article exists in the form of the number "one" як yak and -е -e, the first positioned before the noun and the second joining the noun as a suffix. When a noun is used as a direct object, it is marked by the suffix -ро -ro, e.g., Рустамро задам Rustam-ro zadam 'I hit Rustam'. This direct object suffix is added to the word after any plural suffixes. The form -ро can be literary or formal. In older forms of the Persian language, -ро could indicate both direct and indirect objects and some phrases used in modern Persian and Tajik have maintained this suffix on indirect objects, as seen in the following example: Худоро шукр Xudo-ro šukr 'Thank God'). Modern Persian does not use the direct object marker as a suffix on the noun, but rather, as a stand-alone morpheme.[35]

Prepositions

| Tajik | English |

|---|---|

| аз (az) | from, through, across |

| ба (ba) | to |

| бар (bar) | on, upon, onto |

| бе (be) | without |

| бо (bo) | with |

| дар (dar) | at, in |

| то (to) | up to, as far as, until |

| чун (čun) | like, as |

Vocabulary

Tajik is conservative in its vocabulary, retaining numerous terms that have long since fallen into disuse in Iran and Afghanistan, such as арзиз arziz 'tin' and фарбеҳ farbeh 'fat'. Most modern loan words in Tajik come from Russian as a result of the position of Tajikistan within the Soviet Union. The vast majority of these Russian loanwords which have entered the Tajik language through the fields of socioeconomics, technology and government, where most of the concepts and vocabulary of these fields have been borrowed from the Russian language. The introduction of Russian loanwords into the Tajik language was largely justified under the Soviet policy of modernisation and the necessary subordination of all languages to Russian for the achievement of a Communist state.[46] Vocabulary also comes from the geographically close Uzbek language and, as is usual in Islamic countries, from Arabic. Since the late 1980s, an effort has been made to replace loanwords with native equivalents, using either old terms that had fallen out of use or coined terminology (including from Iranian Persian). Many of the coined terms for modern items such as гармкунак garmkunak 'heater' and чангкашак čangkašak 'vacuum cleaner' differ from their Afghan and Iranian equivalents, adding to the difficulty in intelligibility between Tajik and other forms of Persian.

In the table below, Persian refers to the standard language of Iran, which differs somewhat from the Dari Persian of Afghanistan. Two other Iranian languages, Pashto and Kurdish (Kurmanji), have also been included for comparative purposes.

| Tajik | моҳ moh |

нав nav |

модар modar |

хоҳар xohar |

шаб šab |

бинӣ binī |

се se |

сиёҳ siyoh |

сурх surx |

зард zard |

сабз sabz |

гург gurg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other Iranian languages | ||||||||||||

| Persian | ماه māh |

نَو naw now |

مادَر mādar |

خْواهَر xāhar |

شَب šab |

بِینِی bīnī |

سِه sē se |

سِياه siyāh |

سُرْخ surx sorx |

زَرْد zard |

سَبْز sabz |

گُرْگ gurg gorg |

| Pashto | مْیاشْت myâsht |

نٙوَی نٙوَے nəway |

مور mor |

خور xor |

ښْپَه shpa |

پوزَه poza |

دْرې dre |

تور tor |

سُور sur |

زْیَړ zyaṛ |

شِين، زٙرْغُون shin, zərghun |

لېوٙه لېوۀ lewə |

| Kurdish (Kurmanji) | meh | nû | dê | xwîşk | şev | poz | sisê, sê | reş | sor | zer | kesk | gur |

| Kurdish (Sorani) | mang | nwê | dayik | xoşk | şew | lût | sê | reş | sûr | zerd | sewz | gurg |

| Other Indo-European languages | ||||||||||||

| English | month | new | mother | sister | night | nose | three | black | red | yellow | green | wolf |

| Armenian | ամիս amis |

նոր nor |

մայր mayr |

քույր k'uyr |

գիշեր gišer |

քիթ k'it' |

երեք yerek' |

սև sev |

կարմիր karmir |

դեղին deġin |

կանաչ kanač |

գայլ gayl |

| Sanskrit | मास māsa |

नव nava |

मातृ mātr̥ |

स्वसृ svasr̥ |

नक्त nakta |

नास nāsa |

त्रि tri |

श्याम śyāma |

रुधिर rudhira |

पीत pīta |

हरित harita |

वृक vr̥ka |

| Russian | месяц mesjac |

новый novyj |

мать matʹ |

сестра sestra |

ночь nočʹ |

нос nos |

три tri |

чёрный čërnyj |

красный, рыжий krasnyj, ryžij |

жёлтый žëltyj |

зелёный zelënyj |

волк volk |

Writing system

In Tajikistan and other countries of the former Soviet Union, Tajik Persian is currently written in the Cyrillic script, although it was written in the Latin script beginning in 1928 and the Arabic alphabet prior to 1928. In the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic, the use of the Latin script was later replaced in 1939 by the Cyrillic script.[47] The Tajik alphabet added six additional letters to the Cyrillic script inventory and these additional letters are distinguished in the Tajik orthography by the use of diacritics.[48]

History

According to many scholars, the New Persian language (which subsequently evolved into the Persian forms spoken in Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan) developed in Transoxiana and Khorasan, in what are today parts of Afghanistan, Iran, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. While the New Persian language was descended primarily from Middle Persian, it also incorporated substantial elements of other Iranian languages of ancient Central Asia, such as Sogdian.

Following the Islamic conquest of Iran and most of Central Asia in the 8th century AD, Arabic for a time became the court language and Persian and other Iranian languages were relegated to the private sphere. In the 9th century AD, following the rise of the Samanids, whose state was centered around the cities of Bukhoro (Buxoro), Samarqand and Herat and covered much of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and northeastern Iran, New Persian emerged as the court language and swiftly displaced Arabic.

New Persian became the lingua franca of Central Asia for centuries, although it eventually lost ground to the Chaghatai language in much of its former domains as a growing number of Turkic tribes moved into the region from the east. Since the 16th century AD, Tajik has come under increasing pressure from neighbouring Turkic languages. Once spoken in areas of Turkmenistan, such as Merv, Tajik is today virtually non-existent in that country. Uzbek has also largely replaced Tajik in most areas of modern Uzbekistan – the Russian Empire in particular implemented Turkification among Tajiks in Ferghana and Samarqand, replacing the dominant language in those areas with Uzbek.[49] Nevertheless, Tajik persisted in pockets, notably in Samarqand, Bukhoro and Surxondaryo Region, as well as in much of what is today Tajikistan.

The creation of the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic within the Soviet Union in 1929 helped to safeguard the future of Tajik, as it became an official language of the republic alongside Russian. Still, substantial numbers of Tajik speakers remained outside the borders of the republic, mostly in the neighbouring Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, which created a source of tension between Tajiks and Uzbeks. Neither Samarqand nor Bukhoro was included in the nascent Tajik SSR, despite their immense historical importance in Tajik history. After the creation of the Tajik SSR, a large number of ethnic Tajiks from the Uzbek SSR migrated there, particularly to the region of the capital, Dushanbe, exercising a substantial influence in the republic's political, cultural and economic life. The influence of this influx of ethnic Tajik immigrants from the Uzbek SSR is most prominently manifested in the fact that literary Tajik is based on their northwestern dialects of the language, rather than the central dialects that are spoken by the natives in the Dushanbe region and adjacent areas.

After the fall of the Soviet Union and Tajikistan's independence in 1991, the government of Tajikistan has made substantial efforts to promote the use of Tajik in all spheres of public and private life. Tajik is gaining ground among the once-Russified upper classes and continues its role as the vernacular of the majority of the country's population. There has been a rise in the number of Tajik publications. Increasing contact with media from Iran and Afghanistan, after decades of isolation under the Soviets, as well as governmental orientation toward a "Persianisation" of the language have brought closer Tajik and the other Persian dialects.

See also

- Academy of Persian Language and Literature

- Bukhori Judeo-Tajik dialect

- Iranian peoples

- Iranian studies

- List of Persian poets and authors

- List of Tajik musicians

- Tajik alphabet

- Surudi Milli

- Help:IPA/Persian

References

- Notes

- Citations

- ↑ Template:E28

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Tajik". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/taji1245.

- ↑ "Tajik". http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=tgk.

- ↑ Lazard, G. 1989

- ↑ Halimov 1974: 30–31

- ↑ Gafforov 1979: 33

- ↑ Studies pertaining to the association between Tajik and Persian include Amanova (1991), Kozlov (1949), Lazard (1970), Rozenfel'd (1961) and Wei-Mintz (1962). The following papers/presentations focus on specific aspects of Tajik and their historical modern Persian counterparts: Cejpek (1956), Jilraev (1962), Lorenz (1961, 1964), Murav'eva (1956), Murav'eva and Rubinl!ik (1959), Ostrovskij (1973) and Sadeghi (1991).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Ido, Shinji; Mahmoodi-Bakhtiari, Behrooz (2023). Tajik Linguistics. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9783110622799. ISBN 978-3-11-062279-9.

- ↑ Lazard, Gilbert (1975), The Rise of the New Persian Language.

- ↑ in Frye, R. N., The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 4, pp. 595–632, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Frye, R. N., "Darī", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Brill Publications, CD version

- ↑ Richard Foltz, A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East, London: Bloomsbury, 2nd ed., 2023, pp. 2–5.

- ↑ "The status of the Russian language in Tajikistan remains unchanged – Rahmon". RIA – RIA.ru. 22 October 2009. https://ria.ru/culture/20091022/190107839.html.

- ↑ "В Таджикистане русскому языку вернули прежний статус". Lenta.ru. http://lenta.ru/news/2011/06/09/russian.

- ↑ Library, International and Area Studies. "LibGuides: Dari Language: Language History" (in en). https://guides.library.illinois.edu/c.php?g=347570&p=2349642.

- ↑ Ben Walter, Gendering Human Security in Afghanistan in a Time of Western Intervention (Routledge 2017), p. 51: for more details, see the article on Tajik people.

- ↑ "Foreign Social Science Bibliographies: Series P-92". 1965. https://books.google.com/books?id=nswoAAAAMAAJ&dq=%22Tadzhik+language%22&pg=PA267.

- ↑ In 1990 the Russian language was declared as the official language of USSR and the constituent republics had rights to declare additional state languages within their jurisdictions. See Article 4 of the Law on Languages of Nations of USSR. (in Russian)

- ↑ ed. Ehteshami 2002, p. 219.

- ↑ ed. Malik 1996, p. 274.

- ↑ Banuazizi & Weiner 1994, p. 33.

- ↑ Siddikzoda, Sukhail (August 2002). "Tajik Language: Farsi or Not Farsi?". Media Insight Central Asia (27). http://www.cimera.org/files/camel/en/27e/MICA27E-Siddikzoda.pdf.

- ↑ B. Rezvani: "Ethno-territorial conflict and coexistence in the Caucasus, Central Asia and Fereydan. Appendix 4: Tajik population in Uzbekistan" ([1]). Dissertation. Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, University of Amsterdam. 2013

- ↑ Paul Bergne: The Birth of Tajikistan. National Identity and the Origins of the Republic. International Library of Central Asia Studies. I.B. Tauris. 2007. Pg. 106

- ↑ Ido, Shinji (2014). "Bukharan Tajik". Journal of the International Phonetic Association 44 (1): 87–102. doi:10.1017/S002510031300011X.

- ↑ Foltz, Richard (2023). A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East, 2nd edition. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-7556-4964-8.

- ↑ Uzbekistan. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency (December 13, 2007). Retrieved on 2007-12-26.

- ↑ See for example the Country report on Uzbekistan, released by the United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor here.

- ↑ Rahim Masov, The History of the Clumsy Delimitation, Irfon Publ. House, Dushanbe, 1991 (in Russian). English translation: The History of a National Catastrophe, transl. Iraj Bashiri, 1996.

- ↑ Rahim Masov. (1996)The History of a National Catastrophe Bashiri Working Papers on Central Asia and Iran

- ↑ "Afghanistan v. Languages". Ch. M. Kieffer. Encyclopædia Iranica, online ed.. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/afghanistan-v-languages. "Persian (2) is the language most spoken in Afghanistan. The native tongue of twenty-five percent of the population ..."

- ↑ "Tajikistan's missing men | Tajikistan | al Jazeera". http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/101east/2013/07/201372393525174524.html.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Windfuhr, Gernot. "Persian and Tajik." The Iranian Languages. New York, NY: Routledge, 2009. 421

- ↑ E.K. Sobirov (Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences). On learning the vocabulary of the Tajik language in modern times, p. 115.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Khojayori, Nasrullo, and Mikael Thompson. Tajiki Reference Grammar for Beginners. Washington, DC: Georgetown UP, 2009.

- ↑ A Beginners' Guide to Tajiki by Azim Baizoyev and John Hayward, Routledge, London and New York, 2003, p. 3

- ↑ Novák, Ľubomír (2013). Problem of Archaism and Innovation in the Eastern Iranian Languages (PhD dissertation). Prague: Univerzita Karlova v Praze, filozofická fakulta. https://www.academia.edu/4896441. Retrieved 2024-07-05.

- ↑ Lazard, G. 1956

- ↑ Perry, J. R. (2005)

- ↑ Nakanishi, Akira, Writing Systems of the World

- ↑ Korotkow, M. (2004)

- ↑ Standard Tajik phonology by Shinji Ido, Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, 2023

- ↑ Ido, Shinji. 2014. Illustrations of the IPA: Bukharan Tajik. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 44. 87–102. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Perry, J. R. 2005

- ↑ Windfuhr, Gernot. Persian Grammar: History and State of Its Study. De Gruyter, 1979. Trends in Linguistics. State-Of-The-Art Reports.

- ↑ Marashi, Mehdi; Jazayery, Mohammad Ali (1994). Persian Studies in North America: Studies in Honor of Mohammad Ali Jazayery. Bethesda, MD: Iranbooks. ISBN 9780936347356.

- ↑ Windfuhr, Gernot. "Persian and Tajik." The Iranian Languages. New York, NY: Routledge, 2009. 420.

- ↑ Windfuhr, Gernot. "Persian and Tajik." The Iranian Languages. New York, NY: Routledge, 2009. 423.

- ↑ Kirill Nourzhanov; Christian Bleuer (8 October 2013). Tajikistan: A Political and Social History. ANU E Press. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-1-925021-16-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=nR6oAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA22.

- Sources

- Baizoyev, Azim; Hayward, John (2004). A beginner's guide to Tajiki. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-31597-2. https://archive.org/details/BeginnerTajik. (includes a Tajiki-English Dictionary)

- Foltz, Richard (2023). A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East, 2nd edition. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7556-4964-8.

- Ido, Shinji (2005). Tajik. München: Lincom Europa. ISBN 3-89586-316-5.

- Korotow, Michael (2004). Tadschikisch Wort für Wort. Bielefeld: Reise Know-How Verlag Peter Rump. ISBN 3-89416-347-X.

- Khojayori, Nasrullo; Thompson, Mikael (2009). Tajiki Reference Grammar for Beginners. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-58901-269-1.

- Lazard, G. (1956). "Caractères distinctifs de la langue tadjik". Bulletin de la Société Linguistique de Paris 52: 117–186.

- Lazard, G. (1989). "Le Persan". in Schmitt, Rüdiger. Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum. Wiesbaden.

- Perry, J. R. (2005). A Tajik Persian Reference Grammar. Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-04-14323-8.

- Marashi, Mehdi, ed (January 1994). Persian studies in North America: Studies in honor of Mohammad Ali Jazayery. Bethesda, MD: Iranbooks. ISBN 978-0-936347-35-6.

- Nazarzoda, Saĭfiddin; Sanginov, Ahmadjon; Karimov, Said; Sulton, Mirzo Hasani (2008) (in tg). Farhangi tafsiri zaboni tojikī. Dushanbe.

- Nazarzoda, Saĭfiddin; Sanginov, Ahmadjon; Karimov, Said; Sulton, Mirzo Hasani (2008) (in tg). Farhangi tafsiri zaboni tojikī. 1. Dushanbe. ISBN 978-99947-715-7-8. https://archive.org/details/farhangitafsirii01naza/.

- Nazarzoda, Saĭfiddin; Sanginov, Ahmadjon; Karimov, Said; Sulton, Mirzo Hasani (2008) (in tg). Farhangi tafsiri zaboni tojikī. 2. Dushanbe. ISBN 978-99947-715-5-4. https://archive.org/details/farhangitafsirii02naza/.

- Rastorgueva, V (1963). A Short Sketch of Tajik Grammar. Mouton. ISBN 0-933070-28-4.

- Windfuhr, Gernot (1979). Persian Grammar: History and State of Its Study. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-9027977748.

- Windfuhr, Gernot (1987). "Persian". in Comrie, B.. The World's Major Languages. pp. 523–546.

- Windfuhr, Gernot (2009). "Persian and Tajik". The Iranian Languages. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1131-4.

Further reading

- Foltz, Richard (2023). A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East, 2nd edition. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7556-4964-8.

- Ido, Shinji (2014). "Bukharan Tajik". Journal of the International Phonetic Association 44 (1): 87–102. doi:10.1017/S002510031300011X.

- John Perry. TAJIK ii. TAJIK PERSIAN (Encyclopædia Iranica)

- Bahriddin Aliev and Aya Okawa. TAJIK iii. COLLOQUIAL TAJIKI IN COMPARISON WITH PERSIAN OF IRAN (Encyclopædia Iranica)

External links

| Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination | тоҷикӣ edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Tajik |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Tajik. |

- Tajiki Cyrillic to Persian alphabet converter

- A Worldwide Community for Tajiks

- Tajik Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- BBC news in Tajik

- English-Tajik-Russian Dictionary

- Free Online Tajik Dictionary

- Welcome to Tajikistan

- Численность населения Республики Таджикистан на 1 января 2015 года. Сообщение Агентства по статистике при Президенте Республики Таджикистан

- намоишгоҳи "Китоби Душанбе". A news clip about a Dushanbe book exhibition, with examples of various members of the public speaking Tajiki.

Template:Persian language Template:Languages of Tajikistan Template:Languages of Uzbekistan

|