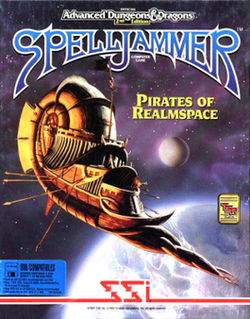

Software:Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace

| Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace | |

|---|---|

Cover art by Erik Olson | |

| Developer(s) | Cybertech |

| Publisher(s) | Strategic Simulations |

| Producer(s) | George MacDonald |

| Designer(s) | Al Escudero |

| Writer(s) | Al Brown Rick E. White |

| Composer(s) | Peter Grisdale Mark McGough |

| Series | Gold Box |

| Platform(s) | MS-DOS |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing, adventure, tactical role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace is a video game for MS-DOS released by Strategic Simulations in 1992. It is a Dungeons & Dragons PC video game using the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, Second Edition rules, and the Spelljammer setting. Spelljammer was programmed and designed by Cybertech Systems.[1]

Plot

In the game, the player captains a ship and crew within the Spelljammer universe. The player can ship goods from planet to planet for a fee and take on simple missions including delivering people and goods, destroying pirates, and guarding the space lanes. As the player completes missions, the player's character gains reputation points, eventually gaining enough points to be asked to help rid Realmspace of a terrible danger. This mission leads to the simple plot in the game.

Gameplay

Spelljammers are magic ships that fly through "wildspace" to various planets. All the planets and wildspace for a system are contained in a Crystal Sphere. Outside the Crystal Sphere is the Phlogiston, also known as the "flow". Holes in the Crystal Sphere allow the flow to shine through, appearing as stars on planets. Spelljamming ships cannot enter the Phlogiston.

Game mechanics

The game starts the player with a 5th level D&D character. The available classes are: Clerics, Fighters, Paladins, Rangers, Mages, and Thieves. There are three main parts to the game: (1) docked at a planet, (2) in space travel and ship-to-ship combat, and (3) on-board personal combat. When at a planet, various text menus allow the player to buy and sell cargo, repair and upgrade their ship, buy and sell character equipment, and seek missions. A rudimentary trade system allows players to make money shipping goods from planet to planet, and some key planets have more options for ship repairs and equipment. In space, the player can travel from planet to planet, or simply point the ship in any direction and go. Real-time ship-to-ship combat using ballistae and catapults takes place in a simple 3D view. The player can steer the ship to aim the weapons at enemies, and to try to avoid enemy missiles. The occasional meteor storm is a minor hazard while spelljamming.

One little-used feature programmed into the game is the ability to crash the player's ship into the Crystal Sphere. Normally "space" is shown as black, but if a player is patient and continues towards the Crystal Sphere, space would turn dark grey, light grey, the stars would spread out, and eventually the ship will crash into the Crystal Sphere.

The player can bring the ship close to an enemy ship, board, and do turn based hand-to-hand combat on a simple isometric map. A full range of spells and weapons is available, and ships are crewed by a wide range of humans and monsters. In the turn-based combat system, the player controls the ship's officers, and the computer controls the regular crew and the enemies. The turn-based combat engine supports spell effects and animations on the map, for example a "stinking cloud" that persists for multiple turns.

Development

Initial phase

Al Escudero was a successful game designer with a couple of commercial titles under his belt working out of Vancouver, Canada in 1990. Escudero had started design work on a space battle game for Strategic Simulations, Inc. (SSI), and put in a few months of effort before SSI decided to kill the project. Design work continued for as long as it did because the decision to kill the project did not trickle down to the level of management Escudero was dealing with for two months after upper management killed the project. To make up for the loss of time and money, SSI quickly found another project for Escudero – Spelljammer.

Escudero designed the ship to ship combat and came up with the idea of using a 2D map, then using the distance between ships to scale the size of the ship's bitmap and display it in a simple 3D view on one plane. He then designed the basic layout of all menus, the overall look and feel of the turn based hand-to-hand combat, and most other key parts of the game. At this time Cybertech Systems was actually just Escudero in his basement. Lead programmer Alex Russell was acquainted with him because he went to high-school with Russell's younger brother. Russell had done a couple of small porting jobs for Escudero in the past. Another programmer named David "Zoid" Kirsch worked on the game for a couple of months. As Russell had only been programming business systems up to now, Zoid's knowledge of PC hardware was valuable at the start of the project.

Artwork

Escudero worked on the art for the game, doing most of the planets, tiles, and much other minor art. Russell also did artwork, doing a few scenes used when at ports, and decorations for menus. They also used a black and white video camera (colour camera was much too expensive for the budget they were working on) and a RGB colour wheel to digitise models, both scale and human, to use for the game. An Amiga was used for digitisation. The Amiga could write to standard PC floppy disks, and Deluxe Paint on the Amiga would write files that PC Deluxe paint could read. Deluxe Paint, and Deluxe Paint Animation were used for 90% of the art. Three freelance artists drew the bulk of the ships and a few ports. Each ship required eight hand drawn pictures, one for each of eight rotations. These eight pictures were then scaled as required for the semi 3D used in ship to ship combat. A 30-second Cybertech introduction of a door opening took four hours to render on a 486, and over 24 hours on a 386.

Cybertech hired a model builder to build one ship, but while this had good results it turned out the model builder could not turn a profit at the price they could pay for a custom model. The asteroids in the game were digitized rocks from Escudero's backyard. A few people in full armor from the local SCA (Society for Creative Anachronism), as well as friends in costumes were digitized as well.

Programming

Russell did 90% of the programming. This was back before the widespread use of the internet, so personal contacts in the local game programming industry, and a good local book store were very important sources of information. 256 colors and 320x200 pixels was chosen for the video mode because it was simple to program, looked good, and would be faster to process a smaller number of pixels with many colors, than many pixels with only 16 colors. This was way before 3D cards – everything was done in software. Most of the game was written in C, except for all the graphic primitives which were written in x86 assembler.

A menu system was written, but not a menu editor. All menus were hard-coded C structures, requiring a full recompile to see a menu change. The over-head turn based combat system had a very good editor written for it. Each ship in the game had its own map. And the semi 3D engine was written. SSI provided the sound library. There were no standards so each common sound card had to be supported. The other interesting routine was the movie player. It looked at a series of computer pictures, found and stored the differences and stored them as compressed blocks. Cybertech hired an assembly whiz to write the de-compressor. Russell wrote everything else from scratch. The team used some of Zoid's ideas, but none of his code made it into the final game.

Music was created by two of Russell's friends, Mark McGough and Peter Grisdale, who were also musicians as well as computer programmers. They already had MIDI equipment and did the music for a copy of the game and a credit listing.

Final phase

Russell later recalled: "We sent game builds down to SSI using a state of the art 9600 baud modem and Zmodem. It took about 3 hours to send down 2 megs of updates, and involved calling voice first, arranging for who would auto-answer (SSI so they could pay the phone bill!), and crossing your fingers".

Development took slightly over a year. The first six months of work was done in Escudero's kitchen. Then SSI called up and said they were coming up to visit. Since Escudero did not want to look like a low budget outfit he quickly rented a small office, where development was finished. After Spelljammer was finished, Escudero was instrumental in developing a multi-line BBS called Ice Online that ran a custom coded MUD. This turned out to be a quite successful enterprise that would eventually take up the whole floor of the building the original small office was in. EA eventually bought out Ice Online, took all the key employees and closed down the BBS.

Reception

Computer Gaming World liked the boarding combat but criticized the bugs and long load times, concluding that the game "is a product with a good deal of promise, thwarted by an unfortunate number of defects". It recommended the game to "AD&D role-playing stalwarts who can look past the problems, but as to the rest of the gaming public, SJammer is still a few updates away from being a product worth playing".[1] The magazine warned that the "grandiose claims" SSI made about the game and Legends of Valour threatened the company's "long-standing reputation for quality".[2] According to GameSpy, it was a "nice try, but a so-called "Gold Box" game everyone can easily miss".[3]

James Trunzo reviewed Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace in White Wolf #37 (July/Aug., 1993) and stated that "The game certainly isn't all bad. It has some new looks, some new encounter types and a smoother icon-based interface. However, the sum of the parts don't add up to a great gaming experience. If you're a big Spelljammer fan, you'll probably want to give the game a try. Otherwise, invest in some of S.S.I.'s better products."[4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 James, Jeff (March 1993). "SSI's Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace". Computer Gaming World (Golden Empire Publications, Inc.) 104: 62–64. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1993&pub=2&id=104.

- ↑ Miller, Chuck (May 1993). "SSI Introduces U.S. Gamers to Legends of Valour". Computer Gaming World: 42. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1993&pub=2&id=106. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ↑ "A History of D&D Video Games - Part II". Game Spy. August 16, 2004. http://pc.gamespy.com/articles/539/539300p4.html.

- ↑ Trunzo, James (July–August 1993). "The Silicon Dungeon". White Wolf Magazine (37): 65. https://imgur.com/a/vYdlufI.

External links

- Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace at Beyond the Moons (the official Spelljammer website)

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

- Spelljammer: Pirates of Realmspace can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

- Review in PC World

|