Tubular neighborhood

This article includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (August 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In mathematics, a tubular neighborhood of a submanifold of a smooth manifold is an open set around it resembling the normal bundle.

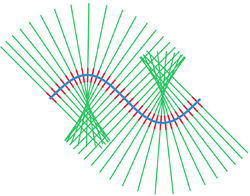

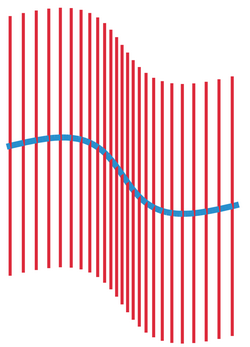

The idea behind a tubular neighborhood can be explained in a simple example. Consider a smooth curve in the plane without self-intersections. On each point on the curve draw a line perpendicular to the curve. Unless the curve is straight, these lines will intersect among themselves in a rather complicated fashion. However, if one looks only in a narrow band around the curve, the portions of the lines in that band will not intersect, and will cover the entire band without gaps. This band is a tubular neighborhood.

In general, let S be a submanifold of a manifold M, and let N be the normal bundle of S in M. Here S plays the role of the curve and M the role of the plane containing the curve. Consider the natural map

- [math]\displaystyle{ i : N_0 \to S }[/math]

which establishes a bijective correspondence between the zero section [math]\displaystyle{ N_0 }[/math] of N and the submanifold S of M. An extension j of this map to the entire normal bundle N with values in M such that [math]\displaystyle{ j(N) }[/math] is an open set in M and j is a homeomorphism between N and [math]\displaystyle{ j(N) }[/math] is called a tubular neighbourhood.

Often one calls the open set [math]\displaystyle{ T = j(N), }[/math] rather than j itself, a tubular neighbourhood of S, it is assumed implicitly that the homeomorphism j mapping N to T exists.

Normal tube

A normal tube to a smooth curve is a manifold defined as the union of all discs such that

- all the discs have the same fixed radius;

- the center of each disc lies on the curve; and

- each disc lies in a plane normal to the curve where the curve passes through that disc's center.

Formal definition

Let [math]\displaystyle{ S \subseteq M }[/math] be smooth manifolds. A tubular neighborhood of [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is a vector bundle [math]\displaystyle{ \pi: E \to S }[/math] together with a smooth map [math]\displaystyle{ J : E \to M }[/math] such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ J \circ 0_E = i }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] is the embedding [math]\displaystyle{ S \hookrightarrow M }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ 0_E }[/math] the zero section

- there exists some [math]\displaystyle{ U \subseteq E }[/math] and some [math]\displaystyle{ V \subseteq M }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ 0_E[S] \subseteq U }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ S \subseteq V }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ J\vert_U : U \to V }[/math] is a diffeomorphism.

The normal bundle is a tubular neighborhood and because of the diffeomorphism condition in the second point, all tubular neighborhood have the same dimension, namely (the dimension of the vector bundle considered as a manifold is) that of [math]\displaystyle{ M. }[/math]

Generalizations

Generalizations of smooth manifolds yield generalizations of tubular neighborhoods, such as regular neighborhoods, or spherical fibrations for Poincaré spaces.

These generalizations are used to produce analogs to the normal bundle, or rather to the stable normal bundle, which are replacements for the tangent bundle (which does not admit a direct description for these spaces).

See also

- Parallel curve (aka offset curve)

- Tube lemma

References

- Raoul Bott, Loring W. Tu (1982). Differential forms in algebraic topology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90613-4.

- Morris W. Hirsch (1976). Differential Topology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90148-5.

- Waldyr Muniz Oliva (2002). Geometric Mechanics. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-44242-1.

|