Weierstrass elliptic function

In mathematics, the Weierstrass elliptic functions are elliptic functions that take a particularly simple form. They are named for Karl Weierstrass. This class of functions is also referred to as ℘-functions and they are usually denoted by the symbol ℘, a uniquely fancy script p. They play an important role in the theory of elliptic functions, i.e., meromorphic functions that are doubly periodic. A ℘-function together with its derivative can be used to parameterize elliptic curves and they generate the field of elliptic functions with respect to a given period lattice.

Motivation

A cubic of the form , where are complex numbers with , cannot be rationally parameterized.[1] Yet one still wants to find a way to parameterize it.

For the quadric ; the unit circle, there exists a (non-rational) parameterization using the sine function and its derivative the cosine function: Because of the periodicity of the sine and cosine is chosen to be the domain, so the function is bijective.

In a similar way one can get a parameterization of by means of the doubly periodic -function and its derivative, namely via . This parameterization has the domain , which is topologically equivalent to a torus.[2]

There is another analogy to the trigonometric functions. Consider the integral function It can be simplified by substituting and : That means . So the sine function is an inverse function of an integral function.[3]

Elliptic functions are the inverse functions of elliptic integrals. In particular, let: Then the extension of to the complex plane equals the -function.[4] This invertibility is used in complex analysis to provide a solution to certain nonlinear differential equations satisfying the Painlevé property, i.e., those equations that admit poles as their only movable singularities.[5]

Definition

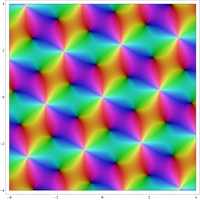

Let be two complex numbers that are linearly independent over and let be the period lattice generated by those numbers. Then the -function is defined as follows:

This series converges locally uniformly absolutely in the complex torus .

It is common to use and in the upper half-plane as generators of the lattice. Dividing by maps the lattice isomorphically onto the lattice with . Because can be substituted for , without loss of generality we can assume , and then define . With that definition, we have .

Properties

- is a meromorphic function with a pole of order 2 at each period in .

- is a homogeneous function in that:

- is an even function. That means for all , which can be seen in the following way:

- The second last equality holds because . Since the sum converges absolutely this rearrangement does not change the limit.

- The derivative of is given by:[6]

- and are doubly periodic with the periods and .[6] This means: It follows that and for all .

Laurent expansion

Let . Then for the -function has the following Laurent expansion where for are so called Eisenstein series.[6]

Differential equation

Set and . Then the -function satisfies the differential equation[6] This relation can be verified by forming a linear combination of powers of and to eliminate the pole at . This yields an entire elliptic function that has to be constant by Liouville's theorem.[6]

Invariants

The coefficients of the above differential equation and are known as the invariants. Because they depend on the lattice they can be viewed as functions in and .

The series expansion suggests that and are homogeneous functions of degree and . That is[7] for .

If and are chosen in such a way that , and can be interpreted as functions on the upper half-plane .

Let . One has:[8] That means g2 and g3 are only scaled by doing this. Set and As functions of , and are so called modular forms.

The Fourier series for and are given as follows:[9] where is the divisor function and is the nome.

Modular discriminant

The modular discriminant is defined as the discriminant of the characteristic polynomial of the differential equation as follows: The discriminant is a modular form of weight . That is, under the action of the modular group, it transforms as where with .[10]

Note that where is the Dedekind eta function.[11]

For the Fourier coefficients of , see Ramanujan tau function.

The constants e1, e2 and e3

, and are usually used to denote the values of the -function at the half-periods. They are pairwise distinct and only depend on the lattice and not on its generators.[12]

, and are the roots of the cubic polynomial and are related by the equation: Because those roots are distinct the discriminant does not vanish on the upper half plane.[13] Now we can rewrite the differential equation: That means the half-periods are zeros of .

The invariants and can be expressed in terms of these constants in the following way:[14] , and are related to the modular lambda function:

Relation to Jacobi's elliptic functions

For numerical work, it is often convenient to calculate the Weierstrass elliptic function in terms of Jacobi's elliptic functions.

The basic relations are:[15] where and are the three roots described above and where the modulus k of the Jacobi functions equals and their argument w equals

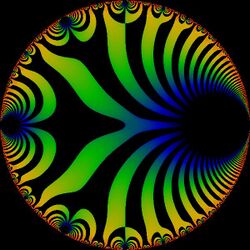

Relation to Jacobi's theta functions

The function can be represented by Jacobi's theta functions: where is the nome and is the period ratio .[16] This also provides a very rapid algorithm for computing .

Relation to elliptic curves

Consider the embedding of the cubic curve in the complex projective plane

where is a point lying on the line at infinity . For this cubic there exists no rational parameterization, if .[1] In this case it is also called an elliptic curve. Nevertheless there is a parameterization in homogeneous coordinates that uses the -function and its derivative :[17]

Now the map is bijective and parameterizes the elliptic curve .

is an abelian group and a topological space, equipped with the quotient topology.

It can be shown that every Weierstrass cubic is given in such a way. That is to say that for every pair with there exists a lattice , such that

and .[18]

The statement that elliptic curves over can be parameterized over , is known as the modularity theorem. This is an important theorem in number theory. It was part of Andrew Wiles' proof (1995) of Fermat's Last Theorem.

Addition theorem

The addition theorem states[19] that if and do not belong to , then This states that the points and are collinear, the geometric form of the group law of an elliptic curve.

This can be proven[20] by considering constants such that Then the elliptic function has a pole of order three at zero, and therefore three zeros whose sum belongs to . Two of the zeros are and , and thus the third is congruent to .

Alternative form

The addition theorem can be put into the alternative form, for :[21]

As well as the duplication formula:[21]

Proofs

This can be proven from the addition theorem shown above. The points and are collinear and lie on the curve . The slope of that line is So , , and all satisfy a cubic where is a constant. This becomes Thus which provides the wanted formula

A direct proof is as follows.[22] Any elliptic function can be expressed as: where is the Weierstrass sigma function and are the respective zeros and poles in the period parallelogram. Considering the function as a function of , we have Multiplying both sides by and letting , we have , so

By definition the Weierstrass zeta function: therefore we logarithmically differentiate both sides with respect to obtaining: Once again by definition thus by differentiating once more on both sides and rearranging the terms we obtain Knowing that has the following differential equation and rearranging the terms one gets the wanted formula

Typography

The Weierstrass's elliptic function is usually written with a rather special, lower case script letter ℘, which was Weierstrass's own notation introduced in his lectures of 1862–1863.[footnote 1] It should not be confused with the normal mathematical script letters P: 𝒫 and 𝓅.

In computing, the letter ℘ is available as \wp in TeX. In Unicode the code point is U+2118 ℘ SCRIPT CAPITAL P, with the more correct alias weierstrass elliptic function.[footnote 2] In HTML, it can be escaped as ℘ or ℘.

| Preview | Template:Charmap/showcharTemplate:Charmap/showcharTemplate:Charmap/showcharTemplate:Charmap/showchar | |

|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | SCRIPT CAPITAL P / WEIERSTRASS ELLIPTIC FUNCTION | |

| Encodings | decimal | hex |

| Unicode | 8472 0 0 0 | U+2118 |

| UTF-8 | 226 132 152 0 0 0 | E2 84 98 00 00 00 |

| Numeric character reference | ℘ |

℘ |

| Named character reference | ℘ | |

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ This symbol was also used in the version of Weierstrass's lectures published by Schwarz in the 1880s. The first edition of A Course of Modern Analysis by E. T. Whittaker in 1902 also used it.[23]

- ↑ The Unicode Consortium has acknowledged two problems with the letter's name: the letter is in fact lowercase, and it is not a "script" class letter, like U+1D4C5 𝓅 MATHEMATICAL SCRIPT SMALL P, but the letter for Weierstrass's elliptic function. Unicode added the alias as a correction.[24][25]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hulek, Klaus. (2012) (in German), Elementare Algebraische Geometrie : Grundlegende Begriffe und Techniken mit zahlreichen Beispielen und Anwendungen (2., überarb. u. erw. Aufl. 2012 ed.), Wiesbaden: Vieweg+Teubner Verlag, p. 8, ISBN 978-3-8348-2348-9

- ↑ Rolf Busam (2006) (in German), Funktionentheorie 1 (4., korr. und erw. Aufl ed.), Berlin: Springer, p. 259, ISBN 978-3-540-32058-6

- ↑ Jeremy Gray (2015) (in German), Real and the complex: a history of analysis in the 19th century, Cham, p. 71, ISBN 978-3-319-23715-2

- ↑ Rolf Busam (2006) (in German), Funktionentheorie 1 (4., korr. und erw. Aufl ed.), Berlin: Springer, p. 294, ISBN 978-3-540-32058-6

- ↑ Ablowitz, Mark J.; Fokas, Athanassios S. (2003). Complex Variables: Introduction and Applications. Cambridge University Press. p. 185. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511791246. ISBN 978-0-521-53429-1.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Apostol, Tom M. (1976) (in German), Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory, New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 11, ISBN 0-387-90185-X

- ↑ Apostol, Tom M. (1976). Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 14. ISBN 0-387-90185-X. OCLC 2121639.

- ↑ Apostol, Tom M. (1976) (in German), Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory, New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 14, ISBN 0-387-90185-X

- ↑ Apostol, Tom M. (1990). Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 20. ISBN 0-387-97127-0. OCLC 20262861.

- ↑ Apostol, Tom M. (1976). Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 50. ISBN 0-387-90185-X. OCLC 2121639.

- ↑ Chandrasekharan, K. (Komaravolu), 1920- (1985). Elliptic functions. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 122. ISBN 0-387-15295-4. OCLC 12053023.

- ↑ Busam, Rolf (2006) (in German), Funktionentheorie 1 (4., korr. und erw. Aufl ed.), Berlin: Springer, p. 270, ISBN 978-3-540-32058-6

- ↑ Apostol, Tom M. (1976) (in German), Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory, New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 13, ISBN 0-387-90185-X

- ↑ K. Chandrasekharan (1985) (in German), Elliptic functions, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, p. 33, ISBN 0-387-15295-4

- ↑ Korn GA, Korn TM (1961). Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers. New York: McGraw–Hill. pp. 721.

- ↑ Reinhardt, W. P.; Walker, P. L. (2010), "Weierstrass Elliptic and Modular Functions", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F. et al., NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-19225-5, http://dlmf.nist.gov/23.6.E7

- ↑ Hulek, Klaus. (2012) (in German), Elementare Algebraische Geometrie : Grundlegende Begriffe und Techniken mit zahlreichen Beispielen und Anwendungen (2., überarb. u. erw. Aufl. 2012 ed.), Wiesbaden: Vieweg+Teubner Verlag, p. 12, ISBN 978-3-8348-2348-9

- ↑ Hulek, Klaus. (2012) (in German), Elementare Algebraische Geometrie : Grundlegende Begriffe und Techniken mit zahlreichen Beispielen und Anwendungen (2., überarb. u. erw. Aufl. 2012 ed.), Wiesbaden: Vieweg+Teubner Verlag, p. 111, ISBN 978-3-8348-2348-9

- ↑ Watson; Whittaker (1927), A course in modern analysis (4 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 440–441

- ↑ Watson; Whittaker (1927), A course in modern analysis (4 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 440–441

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Rolf Busam (2006) (in German), Funktionentheorie 1 (4., korr. und erw. Aufl ed.), Berlin: Springer, p. 286, ISBN 978-3-540-32058-6

- ↑ Akhiezer (1990), Elements of the theory of elliptic functions, AMS, pp. 40–41

- ↑ teika kazura (2017-08-17), The letter ℘ Name & origin?, MathOverflow, https://mathoverflow.net/q/278130, retrieved 2018-08-30

- ↑ "Known Anomalies in Unicode Character Names". Unicode Technical Note #27. Unicode, Inc.. 2017-04-10. http://unicode.org/notes/tn27/.

- ↑ "NameAliases-10.0.0.txt". Unicode, Inc.. 2017-05-06. https://www.unicode.org/Public/10.0.0/ucd/NameAliases.txt.

- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene Ann, eds (1983). "Chapter 18". Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. Applied Mathematics Series. 55 (Ninth reprint with additional corrections of tenth original printing with corrections (December 1972); first ed.). Washington D.C.; New York: United States Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards; Dover Publications. pp. 627. LCCN 65-12253. ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0. http://www.math.sfu.ca/~cbm/aands/page_627.htm.

- N. I. Akhiezer, Elements of the Theory of Elliptic Functions, (1970) Moscow, translated into English as AMS Translations of Mathematical Monographs Volume 79 (1990) AMS, Rhode Island ISBN 0-8218-4532-2

- Tom M. Apostol, Modular Functions and Dirichlet Series in Number Theory, Second Edition (1990), Springer, New York ISBN 0-387-97127-0 (See chapter 1.)

- K. Chandrasekharan, Elliptic functions (1980), Springer-Verlag ISBN 0-387-15295-4

- Konrad Knopp, Funktionentheorie II (1947), Dover Publications; Republished in English translation as Theory of Functions (1996), Dover Publications ISBN 0-486-69219-1

- Serge Lang, Elliptic Functions (1973), Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-04162-6

- E. T. Whittaker and G. N. Watson, A Course of Modern Analysis, Cambridge University Press, 1952, chapters 20 and 21

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Weierstrass elliptic functions", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/w097450

- Weierstrass's elliptic functions on Mathworld.

- Chapter 23, Weierstrass Elliptic and Modular Functions in DLMF (Digital Library of Mathematical Functions) by W. P. Reinhardt and P. L. Walker.

- Weierstrass P function and its derivative implemented in C by David Dumas

|