Biology:Autobiographical memory

Autobiographical memory is a memory system consisting of episodes recollected from an individual's life, based on a combination of episodic (personal experiences and specific objects, people and events experienced at particular time and place) and semantic (general knowledge and facts about the world) memory.[1] It is thus a type of explicit memory.

Formation

Conway and Pleydell-Pearce (2000) proposed that autobiographical memory is constructed within a self-memory system (SMS), a conceptual model composed of an autobiographical knowledge base and the working self.[2]

Autobiographical knowledge base

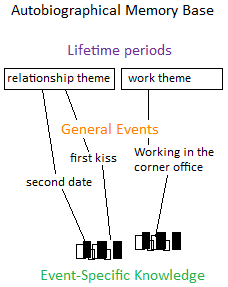

The autobiographical knowledge base contains knowledge of the self, used to provide information on what the self is, what the self was, and what the self can be.[3] This information is categorized into three broad areas: lifetime periods, general events, and event-specific knowledge.[2]

Lifetime periods are composed of general knowledge about a distinguishable and themed time in an individual's life. For example, the period spent at school (school theme), or entering the workforce (work theme). Lifetime periods have a distinct beginning and ending, but they are often fuzzy and overlap.[2] Lifetime periods contain thematic knowledge about the features of that period, such as the activities, relationships, and locations involved, as well as temporal knowledge about the duration of the period.[2] The thematic information in these periods can be used to group them together under broader themes, which can reflect personal attitudes or goals.[2] As an example, a lifetime period with the theme of "when I lost my job" could fall under the broader category of either "when everything went downhill for me" or "minor setbacks in my life."

General events are more specific than lifetime periods and encompass single representations of repeated events or a sequence of related events.[2] General events group into clusters with a common theme, so that when one memory of a general event is recalled, it cues the recall of other related events in memory. These clusters of memories often form around the theme of either achieving or failing to achieve personal goals.[2] Clusters of general events that fall under the category of "first-time" achievements or occasions seem to have a particular vividness, such as the first time kissing a romantic partner, or the first time going to a ball game.[4] These memories of goal-attainment pass on important information about the self, such as how easily a skill can be acquired, or an individual's success and failure rates for certain tasks.[2]

Event-specific knowledge (ESK) is vividly detailed information about individual events, often in the form of visual images and sensory-perceptual features.[2] The high levels of detail in ESK fade very quickly, though certain memories for specific events tend to endure longer.[5] Originating events (events that mark the beginning of a path towards long-term goals), turning points (events that re-direct plans from original goals), anchoring events (events that affirm an individuals beliefs and goals) and analogous events (past events that direct behaviour in the present) are all event specific memories that will resist memory decay.[5]

The sensory-perceptual details held in ESK, though short-lived, are a key component in distinguishing memory for experienced events from imagined events.[6] In the majority of cases, it is found that the more ESK a memory contains, the more likely the recalled event has actually been experienced.[6] Unlike lifetime periods and general events, ESK are not organized in their grouping or recall. Instead, they tend to simply 'pop' into the mind.[2] ESK is also thought to be a summary of the content of episodic memories, which are contained in a separate memory system from the autobiographical knowledge base.[3] This way of thinking could explain the rapid loss of event-specific detail, as the links between episodic memory and the autobiographical knowledge base are likewise quickly lost.[3]

These three areas are organized in a hierarchy within the autobiographical knowledge base and together make up the overall life story of an individual.[3] Knowledge stored in lifetime periods contain cues for general events, and knowledge at the level of general events calls upon event-specific knowledge.[2] When a cue evenly activates the autobiographical knowledge base hierarchy, all levels of knowledge become available and an autobiographical memory is formed.[2]

When the pattern of activation encompasses episodic memory, then autonoetic consciousness may result.[3] Autonoetic consciousness or recollective experience is the sense of "mental time travel" that is experienced when recalling autobiographical memories.[3] These recollections consist of a sense of self in the past and some imagery and sensory-perceptual details.[1] Autonoetic consciousness reflects the integration of parts of the autobiographical knowledge base and the working self.[3]

Working self

The working self, often referred to as just the 'self', is a set of active personal goals or self-images organized into goal hierarchies. These personal goals and self-images work together to modify cognition and the resulting behavior so an individual can operate effectively in the world.[1]

The working self is similar to working memory: it acts as a central control process, controlling access to the autobiographical knowledge base.[3] The working self manipulates the cues used to activate the knowledge structure of the autobiographical knowledge base and in this way can control both the encoding and recalling of specific autobiographical memories.[3]

The relationship between the working self and the autobiographical knowledge base is reciprocal. While the working self can control the accessibility of autobiographical knowledge, the autobiographical knowledge base constrains the goals and self-images of the working self within who the individual actually is and what they can do.[3]

Types

There are four main categories for the types of autobiographical memories:

- Biographical or Personal: These autobiographical memories often contain biographical information, such as where one was born or the names of one's parents.[1]

- Copies vs. Reconstructions: Copies are vivid autobiographical memories of an experience with a considerable amount of visual and sensory-perceptual detail. Such autobiographical memories have different levels of authenticity. Reconstructions are autobiographical memories that are not reflections of raw experiences, but are rebuilt to incorporate new information or interpretations made in hind-sight.[1]

- Specific vs. Generic: Specific autobiographical memories contain a detailed memory of a certain event (event-specific knowledge); generic autobiographical memories are vague and hold little detail other than the type of event that occurred. Repisodic autobiographical memories can also be categorized into generic memories, where one memory of an event is representative of a series of similar events.[1]

- Field vs. Observer: Autobiographical memories can be experienced from different perspectives. Field memories are memories recollected in the original perspective, from a first-person point of view. Observer memories are memories recollected from a perspective outside ourselves, a third-person point of view.[1] Typically, older memories are recollected through an observer perspective,[7] and observer memories are more often reconstructions while field memories are more vivid like copies.[1]

Autobiographical memories can also be differentiated into Remember vs. Know categories. The source of a remembered memory is attributed to personal experience. The source of a known memory is attributed to an external source, not personal memory. This can often lead to source-monitoring error, wherein a person may believe that a memory is theirs when the information actually came from an external source.[8]

Functions

Autobiographical memory serves three broad functions: directive, social, and self-representative.[9] A fourth function, adaptive, was proposed by Williams, Conway and Cohen (2008).[1]

The directive function of autobiographical memory uses past experiences as a reference for solving current problems and a guide for our actions in the present and the future.[1] Memories of personal experiences and the rewards and losses associated with them can be used to create successful models, or schemas, of behavior. which can be applied over many scenarios.[10] In instances where a problem cannot be solved by a generic schema, a more specific memory of an event can be accessed in autobiographical memory to give some idea of how to confront the new challenge.[1]

The social function of autobiographical memory develops and maintains social bonds by providing material for people to converse about.[9] Sharing personal memories with others is a way to facilitate social interaction.[1] Disclosing personal experiences can increase the intimacy level between people and reminiscing of shared past events strengthens pre-existing bonds.[1] The importance of this function can easily be seen in individuals with impaired episodic or autobiographical memory, where their social relationships suffer greatly as a result.[11]

Autobiographical memory performs a self-representative function by using personal memories to create and maintain a coherent self-identity over time.[1] This self-continuity is the most commonly referred to self-representative function of autobiographical memory.[9] A stable self-identity allows for evaluation of past experiences, known as life reflection, which leads to self-insight and often self-growth.[9]

Finally, autobiographical memory serves an adaptive function. Recalling positive personal experiences can be used to maintain desirable moods or alter undesirable moods.[11] This internal regulation of mood through autobiographical memory recall can be used to cope with negative situations and impart an emotional resilience.[1] The effects of mood on memory are explained in better detail under the Emotion section.

Memory Disorder

There are many sorts of amnesia, and by studying their different forms, it has become possible to observe apparent defects in individual subsystems of the brain's memory systems, and thus hypothesize their function in the normally working brain. Other neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease [12] can also affect memory and cognition. Hyperthymesia, or hyperthymestic syndrome, is a disorder that affects an individual's autobiographical memory, essentially meaning that they cannot forget small details that otherwise would not be stored.[13] SDAM is a severe autobiographical memory deficiency, but without amnesia.[14][15]

Memory perspectives

People often re-experience visual images when remembering events; one specific aspect of these images is their perspective.[16] Basically, there are two types of perspective:

- The field perspective is the type of autobiographical memory recalled from the field of perspective that occurred when the memory was encoded.[17] That is, the remembering person doesn't "see" themselves, they see the situation just as they saw it when it happened, through their own eyes. The field of view in such memories corresponds to that of the original situation.

- The observer perspective is an autobiographical memory recalled from an observer position, i.e. viewing the action as an outsider.[17] In other words, the remembering person "sees" the whole situation, with themselves in it. The event is viewed from an external vantage point. There is a wide variation in the spatial locations of this external vantage point, with the location of these perspectives depending on the event being recalled.[16]

The field and observer perspectives have also been described as "pre-reflective" and "reflective," respectively.[18] Different brain regions are activated by the pre-reflective and reflective perspectives.[18]

Moderators of perspective

Studies tested the prevalence of field and observer memories to determine which kind of memories occur at which times. Some of the moderators that change individuals' recalled perspectives are memory age, emotionality, and self-awareness.[17] Additionally, emotion and affect are associated with the field perspective's brain region, while complex cognitive processing is associated with the observer perspective's brain region.[18] The many factors that contribute to determining memory perspective are not affected by whether the recall of the memory was voluntary or involuntary.[19]

- Memory age is the amount of time that has passed since the event.[17] Memory age appears to be one of the most important determinants of perspective type. Recent memories are often experienced in the field perspective; as memory age increases, there is also an increase in the number of observer memories.[17] Perspective is most difficult to change in older memories, especially childhood memories.[17]

- Emotionality refers to the emotional state of the individual at the time that the memory is encoded.[17] Events that were relatively low in emotional experience are often remembered from a field perspective. Events higher in emotion are more likely to be remembered from an observer perspective.[17][20][21] When participants were asked to focus on feelings at retrieval of memories, they more often classified their memories as the field perspective.[4][17]

- Self-awareness refers to the reported amount of consciousness an individual had of themselves at the time of the event.[17] A higher level of self-awareness is often associated with observer memories instead of field memories.[4][failed verification][17]

Cultural effects

Studies have shown that culture can affect the point of view autobiographical memory is recalled in. People living in Eastern cultures are more likely to recall memories through an observer point of view than those living in Western cultures.[22] Also, in Eastern cultures, situation plays a larger role in determining the perspective of memory recall than in Western cultures. For example, Easterners are more likely than Westerners to use observer perspective when remembering events where they are at the center of attention (like giving a presentation, having a birthday party, etc.).[23]

There are many reasons for these differences in autobiographical perspectives across cultures. Each culture has its own unique set of factors that affect the way people perceive the world around them, such as uncertainty avoidance, masculinity, and power distance.[23] While these various cultural factors contribute to shaping one's memory perspective, the biggest factor in shaping memory perspective is individualism.[23] One's sense of self is important in influencing whether autobiographical memories are recalled in the observer or field point of view. Western society has been found to be more individualistic, with people being more independent and stressing less importance on familial ties or the approval of others.[22] On the other hand, Eastern cultures are thought of as less individualistic, focusing more on acceptance and maintaining family relationships while focusing less on the individual self.[22]

The way people in different cultures perceive the emotions of the people around them also play a role in shaping the recall perspective of memories. Westerners are said to have a more "inside-out view" of the world, and unknowingly project their current emotions onto the world around them. This practice is called egocentric projection. For example, when a person is feeling guilty about something he did earlier, he will perceive the people around him as also feeling guilty.[22] On the other hand, Easterners have a more "outside-in view" of the world, perceiving the people around them as having complementary emotions to their own.[22] With an outside-in view, someone who was feeling guilt would imagine the people around them looking upon them with scorn or disgust. These different perceptions across cultures of how one is viewed by others lead to different amounts of field or observer recall.[22]

Effects of gender

Women on average report more memories in the observer perspective than men.[24] A theory for this phenomenon is that women are more conscious about their personal appearance than men.[24] According to objectification theory, social and cultural expectations have created a society where women are far more objectified than men.[24]

In situations where one's physical appearance and actions are important (for example, giving a speech in front of an audience), the memory of that situation will likely be remembered in the observer perspective.[24] This is due to the general trend that when the focus of attention in a person's memory is on themselves, they will likely see themselves from someone else's point of view. This is because, in "center-of-attention" memories, the person is conscious about the way they are presenting themselves and instinctively try to envision how others were perceiving them.[24]

Since women feel more objectified than men, they tend to be put in center-of-attention situations more often, which results in recalling more memories from the observer perspective. Studies also show that events with greater social interaction and significance produce more observer memories in women than events with low or no social interaction or significance.[24] Observer perspective in men was generally unaffected by the type of event.[24]

Effects of personal identity

Another theory of the visual perspective deals with the continuity or discontinuity of the self.[21] Continuity is seen as a way to connect and strengthen the past self to the current self and discontinuity is distanced from the self.[21] This theory breaks down the observer method (i.e. when an individual recalls memories as an observer) into two possibilities: the "dispassionate observer" and the "salient self".[21]

- In the dispassionate observer's view, the field perspective is used when an individual has continuity with the self (their present idea of their self matches the self they were in the past) whereas the observer perspective is used for discontinuity or inauthenticity of the self (when the remembered self is not the same as the present self).[25]

- People who picture their past self as different or conflicting with their current self often recall memories of their old self using the observer perspective.[25] People who have undergone some kind of change often look upon their past self (before the change) as if they were a completely different person.[25] These drastic personal changes include things like graduating, getting over an addiction, entering or leaving prison, getting diagnosed with cancer, losing weight, and any other major life events.[25] There is a split between the present self that is remembering and the past self that is remembered.[25]

- In the salient self's view the observer has the opposite pattern: if an individual perceives continuity with the self (old self matches new self), they would approach this with an observer perspective, contrasted to having discontinuity or incongruence (old self does not match new self) that would be approached with the field perspective.[21]

Thus, the visual perspective employed for continuous and discontinuous memories is the opposite for each view.[21]

People who use observer perspective to remember their old self tend to believe that they are less likely to revert to their old self.[26] When a person recalls memories from the observer perspective, it helps preserve their self-image and self-esteem.[26] Remembering a traumatic or embarrassing event from an observer perspective helps detach that person from that negative event, as if they were not the one experiencing it, but rather someone else.[26] Given the distancing nature of observer perspective, it also results in a worse sense of self-continuity.[26]

Effects of trauma

Events high in emotional content, such as stressful situations (ex: fighting in the Vietnam War), are likely to be recalled using observer perspective, while memories low in emotional content (ex: driving to work) are likely to be recalled using field perspective.[20]

The main reason for this is probably that the observer perspective distances the person from the traumatic event, allowing them to recall the specifics and details of the event without having to relive the feelings and emotions.[27] The observer perspective tends to focus more on one's physical appearance, along with the spatial relations and peripheral details of the scene, which allows people to remember the specifics and important facts of their traumatic experience, without reliving most of the pain.[25] The field perspective, on the other hand, focuses on the physical and psychological feelings experienced at the time of the event. For many people, it can be too difficult to use this perspective to recall the event.[27]

Clinical psychologists have found that the observer perspective acts like a psychological "buffer" to decrease the stress an individual feels when recalling a difficult memory.[21] This is especially seen in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[21] When patients with PTSD were asked to recall their traumatic experience, 89 percent of those who used observer perspective to recall the traumatic event said they did so because it was emotionally easier and spared them from reliving the horror of their traumatic event.[27] Although this is a useful coping mechanism, some argue that effective treatment of PTSD requires the patient to re-experience the emotions and fear from that traumatic event so that it can be processed into something less distressing.[27] Peter Lang and other researchers have hypothesized that the short-term relief the observer perspective provides may actually impede long-term recovery from PTSD.[27]

Methods of study

Diaries

Memory can be inaccurate and critical details of a raw experience can be forgotten or re-imagined.[28] The diary method of study circumvents these issues by having groups of participants keep a diary over a period of weeks or months, during which they record the details of everyday events that they judge to be memorable. In this way a record of true autobiographical memories can be collected.[28]

These true autobiographical memories can then be presented to the participants at a later date in a recognition test, often in comparison to falsified diary entries or 'foils'.[28] The results from these studies can give us information about the level of detail retained in autobiographical memory over time, and if certain features of an event are more salient and memorable in autobiographical memory.[28][29]

A study performed by Barclay and Wellman (1986) included two types of foils in their recognition task: ones that were entirely false and ones that were the original diary entry with a few details altered.[29] Against the false foils, participants were found to be highly accurate at recognizing their true entries (at an average rate of 95%) and false foils were only judged as true 25% of the time.[29] However, when judging between true diary entries and the altered foils, the altered foils were incorrectly judged as true 50% of the time.[29] Barclay and Wellman theorized this was due to the tendency to group similar or repeated autobiographical memories into generic memories or schemas, and thus diary entries that seemed familiar enough to fit into these schemas would be judged as true.[29]

Memory probe

Originally devised by Galton (1879), the memory probe method uses a list of words as cues to bring to mind autobiographical memories, which the participant then tries to describe in as much detail as possible.[30][31] The answers can then be analyzed in order to gain a better understanding as to how recall of autobiographical memory works, especially in cases dealing with brain damage or amnesia.[32]

Recent studies have used non-verbal cues for memory, such as visual images, music[33] or odours. Chu and Downes (2002) found ample evidence that odour cues are particularly good at cueing autobiographical memories.[34] Odour-cued memories for specific events were more detailed and more emotionally loaded than those for verbal, visual, or non-related odour cues.[34]

Emotion

Emotion affects the way autobiographical memories are encoded and retrieved. Emotional memories are reactivated more, they are remembered better and have more attention devoted to them.[35] Through remembering our past achievements and failures, autobiographical memories affect how we perceive and feel about ourselves.[36]

Positive

Positive autobiographical memories contain more sensory and contextual details than negative and neutral memories.[35] People high in self-esteem recall more details for memories where the individual displayed positive personality traits than memories dealing with negative personality traits.[36] People with high self-esteem also devoted more resources to encoding these positive memories over negative memories.[36] In addition, it was found that people high in self-esteem reactivate positive memories more often than people with low self-esteem, and reactivate memories about other people's negative personality traits more often to maintain their positive self-image.[36]

Positive memories appear to be more resistant to forgetting. All memories fade, and the emotions linked with them become less intense over time.[37] However, this fading effect is seen less with positive memories than with negative memories, leading to a better remembrance of positive memories.[37]

As well, recall of autobiographical memories that are important in defining ourselves differs depending on the associated emotion. Past failures seem farther away than past achievements, regardless if the actual length of time is the same.[36]

Negative

Negative memories generally fade faster than positive memories of similar emotional importance and encoding period.[37] This difference in retention period and vividness for positive memories is known as the fading affect bias.[38] In addition, coping mechanisms in the mind are activated in response to a negative event, which minimizes the stress and negative events experienced.[38]

While it seems adaptive to have negative memories fade faster, sometimes it may not be the case. Remembering negative events can prevent us from acting overconfident or repeating the same mistake, and we can learn from them in order to make better decisions in the future.[36]

However, increased remembering of negative memories can lead to the development of maladaptive conditions. The effect of mood-congruent memory, wherein the mood of an individual can influence the mood of the memories they recall, is a key factor in the development of depressive symptoms for conditions such as dysphoria or major depressive disorder.[39]

Dysphoria: Individuals with mild to moderate Dysphoria show an abnormal trend of the fading effect bias. The negative memories of dysphoric individuals did not fade as quickly relative to control groups, and positive memories faded slightly faster.[38] In severely dysphoric individuals the fading affect bias was exacerbated; negative memories faded more slowly and positive memories faded more quickly than non-dysphoria individuals.[38]

Unfortunately, this effect is not well understood. One possible explanation suggests that, in relation to mood-congruent memory theory, the mood of the individual at the time of recall rather than the time of encoding has a stronger effect on the longevity of negative memories.[38] If this is the case, further studies should hopefully show that changes in mood state will produce changes in the strength of the fading affect bias.[38]

Depression: Depression impacts the retrieval of autobiographical memories. Adolescents with depression tend to rate their memories as more accurate and vivid than never-depressed adolescents, and the content of recollection is different.[40]

Individuals with depression encounter trouble remembering specific personal past events, and instead recall more general events (repeated or recurring events).[41] Specific memory recall can further be inhibited by significant psychological trauma occurring in comorbidity.[40] When a specific episodic memory is recalled by an individual with depression, details for the event are almost non-existent and instead purely semantic knowledge is reported.[42]

The lack of remembered detail especially affects positive memories; generally people remember positive events with more detail than negative events, but the reverse is seen in those with depression.[41] Negative memories will seem more complex and the time of occurrence will be more easily remembered than positive and neutral events.[35] This may be explained by mood congruence theory, as depressed individuals remember negatively charged memories during frequent negative moods.[42] Depressed adults also tend to actively rehearse negative memories, which increases their retention period and vividness.[42]

Another explanation may be the tendency for individuals suffering from depression to separate themselves from their positive memories and focus more on evidence that supports their current negative self-image to keep it intact.[41] Depressed adults also recall positive memories from an observer perspective rather than a field perspective, where they appear as a spectator rather than a participant in their own memory.[42]

Finally, the autobiographical memory differences may be attributed to a smaller posterior hippocampal volume in any individuals going through cumulative stress.[43]

Effects of age

Temporal components

Memory changes with age; the temporal distribution of autobiographical memories across the lifespan, as modelled by Rubin, Wetzler, and Nebes (1986),[44] is separated into three components:

- Childhood or infantile amnesia

- The retention function (recency effect)

- The reminiscence bump

Infantile amnesia concerns memories from very early childhood, before age 6; very few memories before age 3 are available. The retention function is the recollection of events in the first 20 to 30 most recent years of an individual's life. This results in more memories for events closest to the present, a recency effect. Finally, there is the reminiscence bump occurring after around age 40, marked by an increase in the retrieval of memories from ages 10 to 30. For adolescents and young adults the reminiscence bump and the recency effect coincide.[44][45]

Age effects

Autobiographical memory demonstrates only minor age differences, but distinctions between semantic versus episodic memories in older adults compared with younger people have been found.

Episodic to semantic shift

Piolino, Desgranges, Benali, and Eustache (2002) investigated age effects on autobiographical memory using an autobiographical questionnaire that distinguished between the recall of semantic and episodic memory. They proposed a transition from episodic to semantic memory in autobiographical memory recollection with increased age. Using four groups of adults aged 40–79, Piolino and colleagues found evidence for a greater decline in episodic memories with longer retention intervals and a more substantial age-related decline in recall of episodic memory than semantic memory. They also found support for the three components of autobiographical memory, as modeled by David Rubin and colleagues.[45]

Semanticizing memories, generalizing episodic memories by removing the specific temporal and spatial contexts, makes memories more persistent than age-sensitive episodic memories. Recent memories (retention interval) are episodic. Older memories are semanticized, becoming more resilient (reminiscence bump).[45] Semantic memories are less sensitive to age effects. Over time, autobiographical memories may consist more of general information than specific details of a particular event or time. In one study where participants recalled events from five life periods, older adults concentrated more on semantic details which were not tied to a distinct temporal or spatial context. Younger participants reported more episodic details such as activities, locations, perceptions, and thoughts. Even when probed for contextual details, older adults still reported more semantic details compared with younger adults.[46]

Voluntary versus involuntary memories

Research on autobiographical memory has focused on voluntary memories, memories that are deliberately recalled; nevertheless, research has evidenced differential effects of age on involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memory. One study found that fewer involuntary and voluntary memories were reported by older adults compared with younger adults. The voluntary memories of older adults were not as specific and were not recalled as quickly as those of younger adults. There was no consistent distinction between involuntary memories for younger and older adults.[47]

Positivity effect

Several studies have shown a positivity effect for autobiographical memories in older adults. One study found a positivity bias for involuntary memories, where younger adults did not rate their involuntary memories as positively as did older adults. Voluntary memories did not show this difference.[47] Another study found a reminiscence bump for adults in their 20s for happy involuntary memories but not for unhappy involuntary memories. Happy involuntary memories were also more than twice as frequent as unhappy involuntary memories. In older participants, a bump for memories reported as most important and happy was found. The saddest and most traumatic memories showed a declining retention function.[48] The positivity bias could reflect an emphasis on emotional-regulation goals in older adults.[49]

Accuracy

Judging the veracity of autobiographical memories can be a source of difficulty. However, it is important to be able to verify the accurateness of autobiographical memories in order to study them.

Vividness

The vividness of the memory can increase one's belief in the veracity of the memory but not as strongly as spatial context.[50] Some memories are extremely vivid. For the person recalling vivid memories of personal significance, these memories appear to be more accurate than everyday memories. These memories have been termed flashbulb memories. However, flashbulb memories may not be any more accurate than everyday memories when evaluated objectively. In one study, both flash bulb memories of 9/11 and everyday memories deteriorated over time; however, reported vividness, recollection and belief in accuracy of flashbulb memories remained high.[51]

False memories

False memories often do not have as much visual imagery as true memories.[50] In one study comparing the characteristics of true and false autobiographical memories, true memories were reported to be wealthier in "recollective experience" or providing many details of the originally encoded event, by participants and observers. The participants engaging in recall reported true memories as being more important, emotionally intense, less typical, and having clearer imagery. True memories were generally reported to have a field perspective versus an observer perspective. An observer perspective was more prominent in false memories. True memories provided more information, including details about the consequences following the recalled event. However, with repeated recollection, false memories may become more like true memories and acquire greater detail.[52]

False memory syndrome is a controversial condition in which people demonstrate conviction for vivid but false personal memories.[53] False memories and confabulation, reporting events that did not occur, may reflect errors in source-monitoring. Confabulation can be a result of brain damage, but it can also be provoked by methods employed in memory exploration.

Professionals such as therapists, police and lawyers must be aware of the malleability of memory and be wary of techniques that might promote false memory generation.[54]

Neuroanatomy

Neural networks

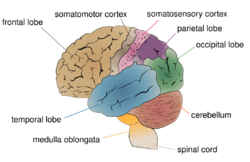

The autobiographical memory knowledge base is distributed through neural networks in the frontal, temporal and occipital lobes. The most abstract or conceptual knowledge is represented in frontal and anterior temporal networks, possibly bilaterally. Sensory and perceptual details of specific events are represented in posterior temporal and occipital networks, predominantly in the right cortex.[55]

A "core" neural network composed of the left medial and ventrolateral prefrontal cortices, medial and lateral temporal cortices, temporoparietal junction, posterior cingulate cortex, and cerebellum[56] are consistently identified as activated regions in at least half of the current imaging studies on autobiographical memory. A "secondary" neural network composed of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, superior medial cortex, superior lateral cortex, anterior cingulate, medial orbitofrontal, temporopolar and occipital cortices, thalamus and amygdala[56] can be identified as active regions in a quarter to a third of imaging studies on autobiographical memory. Regions of the brain that are reported infrequently, in less than a quarter of autobiographical memory imaging studies, include the frontal eye fields, motor cortex, medial and lateral parietal cortices, fusiform gyrus, superior and inferior lateral temporal cortices, insula, basal ganglia and brain stem.[56]

These widespread activation patterns suggest that a number of varying domain-specific processes unique to re-experiencing phenomena, such as emotional and perceptual processes, and domain-general processes, such as attention and memory, are necessary for successful autobiographical memory retrieval.[citation needed]

Construction and retrieval

Autobiographical memories are initially constructed in left prefrontal neural networks. As a memory forms over time, activation then transitions to right posterior networks where it remains at a high level while the memory is held in the mind.[55]

Networks in the left frontal lobe in the dorsolateral cortex and bilaterally in the prefrontal cortex become active during autobiographical memory retrieval. These regions are involved with reconstructive mnemonic processes and self-referential processes, both integral to autobiographical memory retrieval. There is a complex pattern of activation over time of retrieval of detailed autobiographical memories that stimulates brain regions used not only in autobiographical memory, but feature in other memory tasks and other forms of cognition as well.[clarification needed] It is the specific pattern in its totality that distinguishes autobiographical cognition from other forms of cognition.[55]

Maintenance of a detailed memory

Autobiographical memory maintenance is predominantly observed as changing patterns of activity within posterior sensory regions; more specifically, occipitotemporal regions of the right hemisphere.[55]

Individual differences

Autobiographical memory may differ greatly between individuals. A condition named highly superior autobiographical memory is one extreme, in which a person might recall vividly almost every day of their life (usually from around the age of 10). On the other extreme is severely deficient autobiographical memory where a person cannot relive memories from their lives, although this does not affect their everyday functioning.[57][58]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Williams, H. L., Conway, M. A., & Cohen, G. (2008). Autobiographical memory. In G. Cohen & M. A. Conway (Eds.), Memory in the Real World (3rd ed., pp. 21-90). Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 Conway, M. A.; Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. (2000). "The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system". Psychological Review 107 (2): 261–288. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.107.2.261. PMID 10789197.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Conway, M. A. (2005). "Memory and the self". Journal of Memory and Language 53 (4): 594–628. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2005.08.005.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Robinson, J. A. (1992). First experience memories: Contexts and function in personal histories. In M. A. Conway, D. C. Rubin, H. Spinnler, & W. A. Wager (Eds.), Theoretical perspectives on autobiographical memory (pp. 223-239). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Pillemer, D. B. (2001). "Momentous events and the life story". Review of General Psychology 5 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.123.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Johnson, M. K.; Foley, M. A.; Suengas, A. G.; Raye, C. L. (1988). "Phenomenal characteristics of memories for perceived and imagined autobiographical events". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 117 (4): 371–376. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.117.4.371. PMID 2974863.

- ↑ Piolino, P.Expression error: Unrecognized word "etal". (2006). "Autobiographical memory, autonoetic consciousness, and self-perspective in aging". Psychology and Aging 21 (3): 510–525. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.510. PMID 16953713.

- ↑ Hyman, I. E. Jr.; Gilstrap, L. L.; Decker, K.; Wilkinson, C. (1998). "Manipulating remember and know judgements of autobiographical memories: An investigation of false memory creation". Applied Cognitive Psychology 12 (4): 371–386. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0720(199808)12:4<371::aid-acp572>3.0.co;2-u.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Bluck, S.; Alea, N.; Haberman, T.; Rubin, D. C. (2005). "A tale of three functions: The self-reported uses of autobiographical memory". Social Cognition 23 (1): 91–117. doi:10.1521/soco.23.1.91.59198.

- ↑ Pillemer, D. B. (2003). "Directive functions of autobiographical memory: The guiding power of the specific episode". Memory 11 (2): 193–202. doi:10.1080/741938208. PMID 12820831.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Robinson, J. A.; Swanson, K. L. (1990). "Autobiographical memory: The next phase". Applied Cognitive Psychology 4 (4): 321–335. doi:10.1002/acp.2350040407.

- ↑ Acosta, Sandra Antonieta. (2011). Multivariate Anti-inflammatory Approaches to Rescue Neurogenesis and Cognitive function in Aged Animals. OCLC 781835583. http://worldcat.org/oclc/781835583.

- ↑ Marshall, Jessica. "Forgetfulness is key to a healthy mind" (in en-US). https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19726431-600-forgetfulness-is-key-to-a-healthy-mind/.

- ↑ "What is SDAM ?". https://sdamstudy.weebly.com/what-is-sdam.html.

- ↑ Palombo, D. J.; Alain, C.; Söderlund, H.; Khuu, W.; Levine, B. (2015). "Severely deficient autobiographical memory (SDAM) in healthy adults: A new mnemonic syndrome". Neuropsychologia 72: 105–118. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.04.012. PMID 25892594. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25892594/.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Rice, Heather J.; Rubin, David C. (September 2011). "Remembering from any angle: The flexibility of visual perspective during retrieval". Consciousness and Cognition 20 (3): 568–577. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2010.10.013. PMID 21109466.

- ↑ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 17.10 Nigro, Georgia; Neisser, Ulric (October 1983). "Point of view in personal memories". Cognitive Psychology 15 (4): 467–482. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(83)90016-6.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Tagini, Angela; Raffone, Antonino (September 2009). "The 'I' and the 'Me' in self-referential awareness: a neurocognitive hypothesis". Cognitive Processing 11 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1007/s10339-009-0336-1. PMID 19763648.

- ↑ Mace, John H.; Atkinson, Elizabeth; Moeckel, Christopher H.; Torres, Varinia (Jan–Feb 2011). "Accuracy and perspective in involuntary autobiographical memory". Applied Cognitive Psychology 25 (1): 20–28. doi:10.1002/acp.1634.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Rubin, David (1995). Remembering Our Past: Studies in Autobiographical Memory. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9780521657235. https://books.google.com/books?id=jwxVKrn6u9cC&q=memory+field+observer+view&pg=PA89.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 Sutin, A. R. (2008). "Autobiographical memory as a dynamic process: Autobiographical memory mediates basic tendencies and characteristic adaptations". Journal of Research in Personality 42 (4): 1060–1066. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2007.10.002.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Cohen, D.; Gunz, A. (1 January 2002). "As Seen by the Other ... : Perspectives on the Self in the Memories and Emotional Perceptions of Easterners and Westerners". Psychological Science 13 (1): 55–59. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00409. PMID 11892778.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Martin, Maryanne; Jones, Gregory V. (September 2012). "Individualism and the field viewpoint: Cultural influences on memory perspective". Consciousness and Cognition 21 (3): 1498–1503. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2012.04.009. PMID 22673375.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 Huebner, David M.; Fredrickson, Barbara L. (1999). "Gender Differences in Memory Perspectives: Evidence for Self-Objectification in Women". Sex Roles 41 (5/6): 459–467. doi:10.1023/A:1018831001880.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Libby, Lisa K.; Eibach, Richard P. (February 2002). "Looking back in time: Self-concept change affects visual perspective in autobiographical memory.". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82 (2): 167–179. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.2.167. PMID 11831407.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Libby, Lisa K.; Eibach, Richard P.; Gilovich, Thomas (January 2005). "Here's Looking at Me: The Effect of Memory Perspective on Assessments of Personal Change.". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88 (1): 50–62. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.50. PMID 15631574.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 McIsaac, H. K.; Eich, E. (1 April 2004). "Vantage Point in Traumatic Memory". Psychological Science 15 (4): 248–253. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00660.x. PMID 15043642.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Conway, M. A.; Collins, A. F.; Gathercole, S. E.; Anderson, S. J. (1996). "Recollections of true and false autobiographical memories". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 125 (1): 69–95. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.125.1.69.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 Barclay, C. R.; Wellman, H. M. (1986). "Accuracies and inaccuracies in autobiographical memories". Journal of Memory and Language 25 (1): 93–103. doi:10.1016/0749-596x(86)90023-9.

- ↑ Galton, F (1879). "Psychometric experiments". Brain 2 (2): 149–162. doi:10.1093/brain/2.2.149.

- ↑ Rubin, D. C. (Ed.). (1986) Autobiographical memory. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Zola-Morgan, S.; Cohen, N. J.; Squire, L. R. (1983). "Recall of remote episodic memory in amnesia". Neuropsychologia 21 (5): 487–500. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(83)90005-2. PMID 6646401.

- ↑ Platz, Friedrich; Kopiez, Reinhard; Hasselhorn, Johannes; Wolf, Anna (2015). "The impact of song-specific age and affective qualities of popular songs on music-evoked autobiographical memories (MEAMs)". Musicae Scientiae 19 (4): 327–349. doi:10.1177/1029864915597567. http://msx.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/07/31/1029864915597567.abstract.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Chu, S.; Downes, J. J. (2002). "Proust nose best: Odors are better cues of autobiographical memory". Memory and Cognition 30 (4): 511–518. doi:10.3758/bf03194952. PMID 12184552.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 D'Argembeau, A.; Comblain, C.; Van der Linden, M. (2003). "Phenomenal characteristics of autobiographical memories for positive, negative, and neutral events". Applied Cognitive Psychology 17 (3): 281–294. doi:10.1002/acp.856.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 D'Argembeau, A.; Van der Linden, M. (2008). "Remembering pride and shame: Self-enhancement and the phenomenology of autobiographical memory". Memory 16 (5): 538–547. doi:10.1080/09658210802010463. PMID 18569682. http://orbi.ulg.ac.be/jspui/handle/2268/3574.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Walker, W. R.; Vogl, R. J.; Thompson, C. P. (1997). "Autobiographical memory: Unpleasantness fades faster than pleasantness over time". Applied Cognitive Psychology 11 (5): 399–413. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0720(199710)11:5<399::aid-acp462>3.3.co;2-5.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 Walker, W. R.; Skowronski, J.; Gibbons, J.; Vogl, R.; Thompson, C. (2003). "On the emotions that accompany autobiographical memories: Dysphoria disrupts the fading affect bias". Cognition & Emotion 17 (5): 703–723. doi:10.1080/02699930302287.

- ↑ Watkins, P.C.; Vache, K.; Vernay, S.P.; Muller, S. (1996). "Unconscious mood-congruent memory bias in depression". Journal of Abnormal Psychology 105 (1): 34–41. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.105.1.34. PMID 8666709.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Kuyken, W.; Howell, R. (2006). "Facets of autobiographical memory in adolescents with major depressive disorder and never-depressed controls". Cognition & Emotion 20 (3): 466–487. doi:10.1080/02699930500342639. PMID 26529216.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Bergouignan, L.Expression error: Unrecognized word "etal". (2008). "Field perspective deficit for positive memories characterizes autobiographical memory in euthymic depressed patients". Behaviour Research and Therapy 46 (3): 322–333. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2007.12.007. PMID 18243159.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Lemogne, C.; Piolino, P.; Friszer, S.; Claret, A.; Girault, N.; Jouvent, R.; Allilaire, J.; Fossati, P. (2006). "Episodic autobiographical memory in depression: Specificity, autonoetic consciousness, and self perspective". Consciousness and Cognition 15 (2): 258–268. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2005.07.005. PMID 16154765.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer Affects Both the Hippocampus Volume and the Episodic Autobiographical Memory Retrieval.". PLOS ONE 6 (10): e25349. 2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025349. PMID 22016764. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...625349B.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Rubin, D. C.; Schulkind, M. (1997). "The distribution of autobiographical memories across the lifespan". Memory & Cognition 25 (6): 859–866. doi:10.3758/bf03211330. PMID 9421572.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Piolino, P.; Desgranges, B.; Benali, K.; Eustache, F. (2002). "Episodic and semantic remote autobiographical memory in aging". Memory 10 (4): 239–257. doi:10.1080/09658210143000353. PMID 12097209.

- ↑ Levine, B.; Svoboda, E.; Hay, J. F.; Winocur, G.; Moscovitch, M. (2002). "Aging and autobiographical memory: Dissociating episodic from semantic retrieval". Psychology and Aging 17 (4): 677–689. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.17.4.677. PMID 12507363.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Schlagman, S.; Kliegel, M.; Schulz, J.; Kvavilashvili, L. (2009). "Differential effects of age on involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memory". Psychology and Aging 24 (2): 397–411. doi:10.1037/a0015785. PMID 19485657.

- ↑ Berntsen, D.; Rubin, D. C. (2002). "Emotionally charged autobiographical memories across the life span: The recall of happy, sad, traumatic, and involuntary memories". Psychology and Aging 17 (4): 636–652. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.17.4.636. PMID 12507360.

- ↑ Mather, M.; Carstensen, L. L. (2005). "Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory". Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9 (10): 496–502. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. PMID 16154382.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Rubin, D. C.; Schrauf, R. W.; Greenberg, D. L. (2003). "Belief and recollection of autobiographical memories". Memory and Cognition 31 (6): 887–901. doi:10.3758/bf03196443. PMID 14651297.

- ↑ Talarico, J. M.; Rubin, D. C. (2003). "Confidence, not consistency, characterizes flashbulb memories". Psychological Science 14 (5): 455–461. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.02453. PMID 12930476.

- ↑ Heaps, C. M.; Nash, M. (2001). "Comparing recollective experience in true and false autobiographical memories". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 27 (4): 920–930. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.27.4.920. PMID 11486925.

- ↑ Boakes, J (1995). "False memory syndrome". The Lancet 346 (8982): 1048–1049. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91736-5. PMID 7564781.

- ↑ Johnson, M. K.; Raye, C. L. (1998). "False memories and confabulation.". Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2 (4): 137–145. doi:10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01152-8. PMID 21227110.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 Conway, M.A.; Pleydell-Pearce, C.W.; Whitecross, S.E. (2001). "The neuroanatomy of autobiographical memory: a slow cortical potential study of autobiographical memory retrieval". Journal of Memory and Language 45 (3): 493–524. doi:10.1006/jmla.2001.2781.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Svoboda, E.; McKinnon, M.C.; Levine, B. (2006). "The functional neuroanatomy of autobiographical memory: a meta-analysis". Neuropsychologia 44 (12): 2189–2208. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.05.023. PMID 16806314.

- ↑ nscinews.wordpress.com/2018/06/17/highly-superior-and-severely-deficient-autobiographical-memory/

- ↑ Palombo, Daniela J.; Sheldon, Signy; Levine, Brian (2018). "Individual Differences in Autobiographical Memory". Trends in Cognitive Sciences 22 (7): 583–597. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2018.04.007. PMID 29807853.