Organization:Manned Orbiting Laboratory

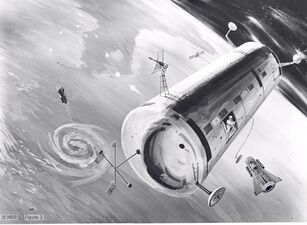

A 1967 conceptual drawing of the Gemini B reentry capsule separating from the MOL at the end of a mission | |

| Station statistics | |

|---|---|

| Crew | 2 |

| Mission status | Canceled |

| Mass | 14,476 kg (31,914 lb) |

| Length | 21.92 m (71.9 ft) |

| Diameter | 3.05 m (10.0 ft) |

| Pressurized volume | 11.3 m3 (399.1 cu ft) |

| Orbital inclination | polar or sun synchronous orbit |

| Days in orbit | 40 days |

| Configuration | |

Configuration of the Manned Orbital Laboratory | |

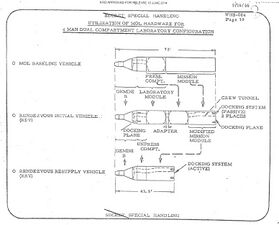

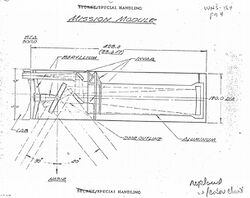

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL), originally referred to as the Manned Orbital Laboratory, was a never-flown part of the United States Air Force 's human spaceflight program, a successor to the canceled Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar military reconnaissance space plane project. The project was developed from several early Air Force and NASA concepts of crewed space stations to be used for reconnaissance purposes. MOL evolved into a single-use laboratory, with which crews would be launched on 40-day missions and return to Earth using a Gemini B spacecraft, derived from NASA's Project Gemini.

The MOL program was announced to the public on 10 December 1963 as an inhabited platform to prove the utility of putting people in space for military missions.[1] Astronauts selected for the program were later told of the reconnaissance mission for the program.[2] The contractor for the MOL was the Douglas Aircraft Company. The Gemini B was externally similar to NASA's Gemini spacecraft, although it underwent several modifications, including the addition of a circular hatch through the heat shield, which allowed passage between the spacecraft and the laboratory.[3]

MOL was canceled in 1969, during the height of the Apollo program, when it was shown that uncrewed reconnaissance satellites could achieve the same objectives much more cost-effectively. U.S. space station development was instead pursued with the civilian NASA Skylab (Apollo Applications Program) which flew in the mid-1970s.

In the 1970s, the Soviet Union launched three Almaz military space stations, similar in intent to the MOL, but cancelled the program in 1977 for the same reasons.

There is a MOL space suit on display at the Oklahoma City Science Museum, presumably never used.[4]

Planned operations

The MOL was planned to use a helium-oxygen atmosphere. It used a Gemini B spacecraft as a reentry vehicle.

The crew were to be launched using a Titan 3M with the stacked Gemini B and MOL, and returned to Earth in the Gemini B. They would conduct up to 40 days of military reconnaissance using large optics, cameras, and side-looking radar.

The USAF Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU) was developed for the MOL project. NASA chief astronaut Deke Slayton later speculated in his autobiography that the AMU may have been developed for MOL because the Air Force "thought they might have the chance to inspect somebody else's satellites."[5]

In response to the announcement of the MOL, the Soviet Union commissioned the development of its own military space station, Almaz. Three Almaz space stations flew as Salyut space stations, and the program also developed a military add-on used on Salyut 6 and Salyut 7.[6][7][8]

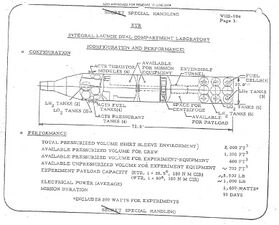

Specifications

- Crew: 2

- Maximum duration: 40 days

- Orbit: Sun synchronous or polar

- Length: 21.92 m (71.9 ft)

- Diameter: 3.05 m (10.0 ft)

- Habitable volume: 11.3 m3 (400 cu ft)

- Gross mass: 14,476 kg (31,914 lb)

- Payload: 2,700 kg (6,000 lb)

- Power: fuel cells or solar cells

- RCS system: N

2O

4/MMH - Reference:[9]

Gallery

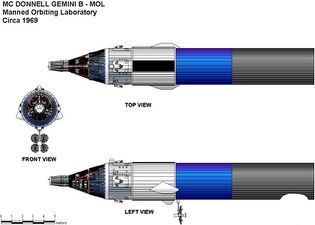

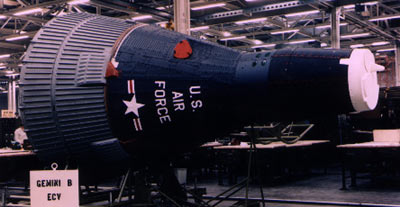

Gemini B

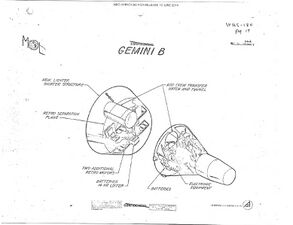

The Gemini capsule was redesigned for MOL and named Gemini B. Externally it was similar to Gemini, but featured a rear hatch for the crew to enter MOL and many specific systems.

Gemini B would be launched with the MOL space station. Once in orbit, the crew would power down the capsule and activate MOL. After about one month of space station operations, the crew would return to the Gemini B capsule, separate from the station and perform reentry. Gemini B had an autonomy of about 14 hours once detached from MOL.[10]

Changes from Gemini

- Systems designed for long term orbital storage (40 days)

- New cockpit layout and instruments[11]

- Helium-oxygen cabin atmosphere, instead of pure oxygen

- Larger heat shield to handle higher energy reentries from polar orbit

- No Orbit Attitude and Maneuvering System (OAMS); capsule orientation for re-entry was handled by the forward Re-entry Control System thrusters only; the laboratory had its own reaction control system for orientation.)

- Number of solid propellant retrorockets increased from four to six; these would be used as abort rockets in case of launch vehicle failure, as well as for deorbit

Reentry module specifications

- Crew: 2

- Maximum duration: 40 days

- Length: 3.35 m (11.0 ft)

- Diameter: 2.32 m (7 ft 7 in)

- Cabin volume: 2.55 m3 (90 cu ft)

- Gross mass: 1,983 kg (4,372 lb)

- RCS thrusters: 16 N × 98 N (3.6 lbf × 22.0 lbf)

- RCS impulse: 283 seconds (2.78 km/s)

- Electric system: 4 kWh (14 MJ)

- Battery: 180 A·h (648,000 C)

- Reference:[12]

Gallery

Gemini B prototype spacecraft (Gemini 2 capsule) used on only MOL test, on display at the Air Force Space and Missile Museum

Astronauts

- MOL Group 1 - November 1965

- Michael J. Adams USAF (1930–1967) – killed on X-15 flight, 15 November 1967

- Albert H. Crews Jr. USAF

- John L. Finley USN (1935–2006)

- Richard E. Lawyer USAF (1932–2005)

- Lachlan Macleay USAF

- Francis G. Neubeck USAF

- James M. Taylor USAF (1930–1970) – killed on T-38 flight, 4 September 1970

- Richard H. Truly USN – Pilot, Space Shuttle Enterprise ALT #2, STS-2; Commander: STS-8; Commander, Naval Space Command as a Vice Admiral; Administrator: NASA, 1989–1992

- MOL Group 2 - June 1966

- Karol J. Bobko USAF – Pilot, STS-6, Commander, STS-51-D, STS-51-J

- Robert L. Crippen USN – Pilot, STS-1, Commander, STS-7, STS-41-C, STS-41-G; Director, Kennedy Space Center, 1992–1995

- C. Gordon Fullerton USAF (1936–2013) – Pilot, Space Shuttle Enterprise ALT #1, STS-3, Commander, STS-51-F

- Henry W. Hartsfield, Jr. USAF (1933–2014) – Pilot, STS-4, Commander, STS-41-D, STS-61-A; Director, Human Exploration and Development of Space Independent Assurance

- Robert F. Overmyer USMC (1936–1996) – Pilot, STS-5, Commander: STS-51-B; killed in Cirrus crash, 22 March 1996

- MOL Group 3 - June 1967

- James A. Abrahamson USAF — Director: Strategic Defense Initiative as a Lieutenant General

- Robert T. Herres USAF (1932–2008) – Vice Chairman: Joint Chiefs of Staff as a General

- Robert H. Lawrence, Jr. USAF (1935–1967) – Killed in training accident, 8 December 1967

- Donald H. Peterson USAF (1933-2018) – Mission specialist: STS-6

Flight schedule

Completed

- 1966 November 3 - MOL mockup and refurbished Gemini 2 capsule launched uncrewed as OPS 0855

Proposed

- 1970 December 1 - MOL 1 - First uncrewed Gemini-B/Titan IIIM qualification flight (Gemini-B flown alone, without an active MOL)

- 1971 June 1 - MOL 2 - Second uncrewed Gemini-B/Titan 3M qualification flight (Gemini-B flown alone, without an active MOL)

- 1972 February 1 - MOL 3 - A crew of two (James M. Taylor, Albert H. Crews) would have spent thirty days in orbit

- 1972 November 1 - MOL 4 - Second crewed mission

- 1973 August 1 - MOL 5 - Third crewed mission

- 1974 May 1 - MOL 6 - Fourth crewed MOL mission. All Navy crew composed of Richard H. Truly and Robert Crippen

- 1975 February 1 - MOL 7 - Fifth crewed MOL

Operational MOLs were to be launched on Titan IIIM rockets from Vandenberg AFB SLC-6 and Cape Canaveral AFS LC-40.[citation needed]

Development

Test Flight

Test flight OPS 0855 for MOL was launched on 3 November 1966 at 13:50:42 UTC on a Titan IIIC-9 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Launch Complex 40. The flight consisted of a MOL mockup built from a Titan II propellant tank, and the refurbished capsule from the Gemini 2 mission as a prototype Gemini B spacecraft.

After the Gemini B prototype separated for a sub-orbital reentry, the MOL mockup continued into orbit and released three satellites. A hatch installed in the Gemini's heat shield—intended to provide access to the MOL during crewed operations—was tested during the capsule's reentry. The Gemini capsule was recovered near Ascension Island in the South Atlantic by the USS La Salle after a flight of 33 minutes.

The Gemini no.2 capsule used in the only flight of the MOL program is on display at the Air Force Space and Missile Museum at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station .[13] A test article at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, is the Gemini B spacecraft (sometimes confused with Blue Gemini). It is recognized by its distinctive "US Air Force" written on the side, and the circular hatch cut through the heat shield.[14]

KH-10

Starting in 1965 a large optical system was added to the spacecraft for military reconnaissance. This camera system was codenamed Dorian and given the designation KH-10. The project was canceled on 10 June 1969 before any operational flights occurred.

The KH-10 intended for the MOL program was succeeded by the uncrewed KH-11 Kennan, which launched in 1976 as the Soviet Union was winding down its crewed space reconnaissance program. The KH-11 is said to have achieved the goal of 3-inch (76 mm) imaging resolution and introduced video transmission of images back to Earth.[2]

Cancellation

A few months after MOL development began, the program also began developing an unmanned version, replacing the crew compartment with several film reentry vehicles. MOL program director Bernard Schriever commissioned a report in May 1966 examining humans' usefulness on the station. The report concluded that they would be useful in several ways, but implied that the program would always need to justify the cost and difficulty of manned MOL versus the unmanned version.[15]

MOL was canceled on 10 June 1969 with the first projected flight three years away. Between 1965 and 1969, MOL's projected cost rose from $1.5 billion to $3 billion while the Vietnam War took larger portions of the defense budget. While Defense Secretary Melvin R. Laird and the Joint Chiefs of Staff strongly supported the station, Central Intelligence Agency head Richard Helms did not support the project because he feared that the death of a MOL astronaut might ground launches and thus damage the nation's satellite reconnaissance program. President Richard Nixon and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger agreed to the Bureau of the Budget's proposal to cancel MOL,[16] as it was determined the capabilities of uncrewed spy satellites met or exceeded the capabilities of crewed MOL missions.

Al Crews said in 2015 that when he saw high-resolution photographs from KH-8 Gambit 3, first launched a few months after the 1966 report, he knew that manned MOL would be canceled.[15] NASA offered those MOL astronauts 35 years of age and under the opportunity to transfer to its astronaut program. Seven of the 14 astronauts were 35 or younger and took the offer, becoming NASA Astronaut Group 7: Future NASA Administrator Richard H. Truly, Karol J. Bobko, Robert Crippen, C. Gordon Fullerton, Henry W. Hartsfield, Robert F. Overmyer, and Donald H. Peterson. All flew on the Space Shuttle.

Declassification

In 2005, two MH-7 training space suits from the MOL program were discovered in a locked room in the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Launch Complex 5 museum on Cape Canaveral.[17] In July 2015, the National Reconnaissance Office declassified over 800 files and photos related to the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program.[18]

In 2019, the National Reconnaissance Office produced a book by historian Courtney V.K. Homer about the MOL program. Titled Spies in Space, the book is based upon the trove of documents released by the NRO and with interviews Ms. Homer conducted with six of the MOL astronauts: Richard Truly, Bob Crippen, Al Crews, Karol Bobko, Lachlan Macleay, and James Abrahamson. It can be downloaded as a free PDF from the NRO’s website. [19]

In fiction

In the 2016 novel Blue Darker Than Black by Mike Jenne, the MOL program is secretly transferred from the Air Force to the United States Navy after its official cancellation in 1969. The Navy launches an ocean surveillance MOL in July 1972. Two Air Force Blue Gemini astronauts fly a rescue mission to the MOL after its crew is incapacitated by the August 4, 1972 solar storm.[20]

See also

- Manned Orbital Development System

- Polyus - Soviet orbital weapons platform

References

- ↑ "Air Force to Develop Manned Orbiting Laboratory" (PDF) (Press release). Department of Defence. 10 December 1963.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "NOVA: Astrospies". PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/astrospies/program.html. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ↑ Slayton & Cassutt 1994, p. 249.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Slayton & Cassutt 1994, p. 174.

- ↑ "The Almaz program". Russian Space Web. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110514000112/http://www.russianspaceweb.com/almaz.html. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ↑ Wade, Mark. "Almaz". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20101119184429/http://astronautix.com/project/almaz.htm. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ↑ Grahn, Sven. "The Almaz Space Station Program". Sven's Space Place. http://www.svengrahn.pp.se/histind/Almprog/almprog.htm. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ↑ "MOL". Astronautix.com. http://www.astronautix.com/m/mol.html.

- ↑ http://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/gemini-b.htm

- ↑ http://www.space1.com/pdf/news1096.pdf

- ↑ "Gemini B RM". Astronautix.com. http://www.astronautix.com/g/geminibrm.html.

- ↑ "Gemini Capsule". Air Force Space & Missile Museum. http://www.afspacemuseum.org/displays/GeminiCapsule/. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ↑ "Gemini Spacecraft". National Museum of the US Air Force. 7 March 2007. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150302112233/http://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=551. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Day, Dwayne A. (2018-03-19). "The Space Review: The measure of a man: Evaluating the role of astronauts in the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program (part 1)". http://www.thespacereview.com/article/3456/1.

- ↑ Heppenheimer, T. A. (1998). The Space Shuttle Decision. NASA. pp. 204–205. SP-4221. OCLC 40305626. https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4221/contents.htm.

- ↑ Nutter, Ashley (2 June 2005). "Suits for Space Spies". NASA.gov. http://www.nasa.gov/vision/space/features/found_mol_spacesuits.html. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ↑ "Index, Declassified Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) Records". National Reconnaissance Office. http://www.nro.gov/Freedom-of-Information-Act-FOIA/Declassified-Records/Special-Collections/MOL/. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ↑ https://www.nro.gov/Portals/65/documents/history/csnr/programs/Spies_In_Space-Reflections_on_MOL_web.pdf?ver=2019-07-11-135535-820×tamp=1562867746595

- ↑ Jenne, Mike (2016). Blue Darker Than Black. Yucca Publishing. ISBN 978-1-63158-066-6.

Bibliography

- Slayton, Donald K. "Deke"; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle (1st ed.). New York: Forge. p. 249. ISBN 0-312-85503-6. OCLC 29845663. https://archive.org/details/dekeusmannedspac00slay/page/249.

External links

- MOL at Encyclopedia Astronautica

- Declassified MOL files by the National Reconnaissance Office

- SSLV-5 No. 9 Post Firing Flight Test Report (Final Evaluation Report) and MOL-EFT Final Flight Test Report (Summary)

- Winfrey, David (16 November 2015). "The last spacemen: MOL and what might have been". The Space Review. http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2866/1.