Double counting (proof technique)

In combinatorics, double counting, also called counting in two ways, is a combinatorial proof technique for showing that two expressions are equal by demonstrating that they are two ways of counting the size of one set. In this technique, which (van Lint Wilson) call "one of the most important tools in combinatorics",[1] one describes a finite set from two perspectives leading to two distinct expressions for the size of the set. Since both expressions equal the size of the same set, they equal each other.

Examples

Multiplication (of natural numbers) commutes

This is a simple example of double counting, often used when teaching multiplication to young children. In this context, multiplication of natural numbers is introduced as repeated addition, and is then shown to be commutative by counting, in two different ways, a number of items arranged in a rectangular grid. Suppose the grid has [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] rows and [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] columns. We first count the items by summing [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] rows of [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] items each, then a second time by summing [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] columns of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] items each, thus showing that, for these particular values of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ n \times m = m \times n }[/math].

Forming committees

One example of the double counting method counts the number of ways in which a committee can be formed from [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] people, allowing any number of the people (even zero of them) to be part of the committee. That is, one counts the number of subsets that an [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-element set may have. One method for forming a committee is to ask each person to choose whether or not to join it. Each person has two choices – yes or no – and these choices are independent of those of the other people. Therefore there are [math]\displaystyle{ 2\times 2\times \cdots 2 = 2^n }[/math] possibilities. Alternatively, one may observe that the size of the committee must be some number between 0 and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]. For each possible size [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math], the number of ways in which a committee of [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] people can be formed from [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] people is the binomial coefficient [math]\displaystyle{ {n \choose k}. }[/math] Therefore the total number of possible committees is the sum of binomial coefficients over [math]\displaystyle{ k=0,1,2,\dots,n }[/math]. Equating the two expressions gives the identity [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{k=0}^n {n \choose k} = 2^n, }[/math] a special case of the binomial theorem. A similar double counting method can be used to prove the more general identity[2] [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{k=d}^n {n\choose k}{k\choose d} = 2^{n-d}{n\choose d} }[/math]

Handshaking lemma

Another theorem that is commonly proven with a double counting argument states that every undirected graph contains an even number of vertices of odd degree. That is, the number of vertices that have an odd number of incident edges must be even. In more colloquial terms, in a party of people some of whom shake hands, an even number of people must have shaken an odd number of other people's hands; for this reason, the result is known as the handshaking lemma.

To prove this by double counting, let [math]\displaystyle{ d(v) }[/math] be the degree of vertex [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math]. The number of vertex-edge incidences in the graph may be counted in two different ways: by summing the degrees of the vertices, or by counting two incidences for every edge. Therefore [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_v d(v) = 2e }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] is the number of edges. The sum of the degrees of the vertices is therefore an even number, which could not happen if an odd number of the vertices had odd degree. This fact, with this proof, appears in the 1736 paper of Leonhard Euler on the Seven Bridges of Königsberg that first began the study of graph theory.

Counting trees

What is the number [math]\displaystyle{ T_n }[/math] of different trees that can be formed from a set of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] distinct vertices? Cayley's formula gives the answer [math]\displaystyle{ T_n=n^{n-2} }[/math]. (Aigner Ziegler) list four proofs of this fact; they write of the fourth, a double counting proof due to Jim Pitman, that it is "the most beautiful of them all."[3]

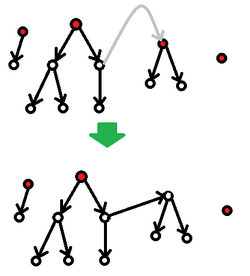

Pitman's proof counts in two different ways the number of different sequences of directed edges that can be added to an empty graph on [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] vertices to form from it a rooted tree. The directed edges point away from the root. One way to form such a sequence is to start with one of the [math]\displaystyle{ T_n }[/math] possible unrooted trees, choose one of its [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] vertices as root, and choose one of the [math]\displaystyle{ (n-1)! }[/math] possible sequences in which to add its [math]\displaystyle{ n-1 }[/math] (directed) edges. Therefore, the total number of sequences that can be formed in this way is [math]\displaystyle{ T_n n(n-1)! = T_n n! }[/math].[3]

Another way to count these edge sequences is to consider adding the edges one by one to an empty graph, and to count the number of choices available at each step. If one has added a collection of [math]\displaystyle{ n-k }[/math] edges already, so that the graph formed by these edges is a rooted forest with [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] trees, there are [math]\displaystyle{ n(k-1) }[/math] choices for the next edge to add: its starting vertex can be any one of the [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] vertices of the graph, and its ending vertex can be any one of the [math]\displaystyle{ k-1 }[/math] roots other than the root of the tree containing the starting vertex. Therefore, if one multiplies together the number of choices from the first step, the second step, etc., the total number of choices is [math]\displaystyle{ \prod_{k=2}^{n} n(k-1) = n^{n-1} (n-1)! = n^{n-2} n!. }[/math] Equating these two formulas for the number of edge sequences results in Cayley's formula: [math]\displaystyle{ \displaystyle T_n n!=n^{n-2}n! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \displaystyle T_n=n^{n-2}. }[/math] As Aigner and Ziegler describe, the formula and the proof can be generalized to count the number of rooted forests with [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] trees, for any [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math].[3]

See also

Additional examples

- Vandermonde's identity, another identity on sums of binomial coefficients that can be proven by double counting.[4]

- Square pyramidal number. The equality between the sum of the first [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] square numbers and a cubic polynomial can be shown by double counting the triples of numbers [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] is larger than either of the other two numbers.

- Lubell–Yamamoto–Meshalkin inequality. Lubell's proof of this result on set families is a double counting argument on permutations, used to prove an inequality rather than an equality.

- Erdős–Ko–Rado theorem, an upper bound on intersecting families of sets, proven by Gyula O. H. Katona using a double counting inequality.[3]

- Proofs of Fermat's little theorem. A divisibility proof by double counting: for any prime [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] and natural number [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], there are [math]\displaystyle{ A^p-A }[/math] length-[math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] words over an [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]-symbol alphabet having two or more distinct symbols. These may be grouped into sets of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] words that can be transformed into each other by circular shifts; these sets are called necklaces. Therefore, [math]\displaystyle{ A^p-A=p\cdot{} }[/math](number of necklaces) and is divisible by [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math].[4]

- Proofs of quadratic reciprocity. A proof by Eisenstein derives another important number-theoretic fact by double counting lattice points in a triangle.

Related topics

- Bijective proof. Where double counting involves counting one set in two ways, bijective proofs involve counting two sets in one way, by showing that their elements correspond one-for-one.

- The inclusion–exclusion principle, a formula for the size of a union of sets that may, together with another formula for the same union, be used as part of a double counting argument.

Notes

References

- Aigner, Martin; Ziegler, Günter M. (1998), Proofs from THE BOOK, Springer-Verlag. Double counting is described as a general principle on page 126; Pitman's double counting proof of Cayley's formula is on pp. 145–146; Katona's double counting inequality for the Erdős–Ko–Rado theorem is pp. 214–215.

- Euler, L. (1736), "Solutio problematis ad geometriam situs pertinentis", Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae 8: 128–140, http://math.dartmouth.edu/~euler/docs/originals/E053.pdf. Reprinted and translated in Biggs, N. L.; Lloyd, E. K.; Wilson, R. J. (1976), Graph Theory 1736–1936, Oxford University Press.

- Garbano, M. L.; Malerba, J. F.; Lewinter, M. (2003), "Hypercubes and Pascal's triangle: a tale of two proofs", Mathematics Magazine 76 (3): 216–217, doi:10.2307/3219324.

- Joshi, Mark (2015), "Double Counting", Proof Patterns, Springer International Publishing, pp. 11–17, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-16250-8_2

- Klavžar, Sandi (2006), "Counting hypercubes in hypercubes", Discrete Mathematics 306 (22): 2964–2967, doi:10.1016/j.disc.2005.10.036.

- van Lint, Jacobus H.; Wilson, Richard M. (2001), A Course in Combinatorics, Cambridge University Press, p. 4, ISBN 978-0-521-00601-9.

|