Medicine:Constrictive pericarditis

| Constrictive pericarditis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pericarditis - constrictive[1] |

| |

| Constrictive pericarditis is defined by a fibrotic (thickened) pericardium. | |

| Symptoms | Fatigue[1] |

| Causes | Tuberculosis, Heart surgery[1] |

| Diagnostic method | CT scan, MRI[1] |

| Treatment | Diuretic, Antibiotics[1] |

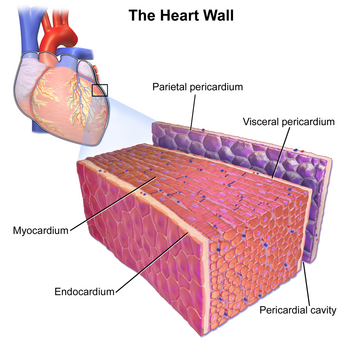

Constrictive pericarditis is a condition characterized by a thickened, fibrotic pericardium, limiting the heart's ability to function normally.[1] In many cases, the condition continues to be difficult to diagnose and therefore benefits from a good understanding of the underlying cause.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of constrictive pericarditis are consistent with the following: fatigue, swollen abdomen, difficulty breathing (dyspnea), swelling of legs and general weakness. Related conditions are bacterial pericarditis, pericarditis and pericarditis after a heart attack.[1]

Causes

The cause of constrictive pericarditis in the developing world are idiopathic in origin, though likely infectious in nature. In regions where tuberculosis is common, it is the cause in a large portion of cases.[3] Causes of constrictive pericarditis include:

- Tuberculosis[4]

- Incomplete drainage of purulent pericarditis[4]

- Fungal and parasitic infections[4]

- Chronic pericarditis[4]

- Postviral pericarditis[4]

- Postsurgical[4]

- Following MI, post-myocardial infarction[4]

- In association with pulmonary asbestos[5]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiological characteristics of constrictive pericarditis are due to a thickened, fibrotic pericardium that forms a non-compliant shell around the heart. This shell prevents the heart from expanding when blood enters it. As pressure on the heart increases, the stroke volume decreases as a result of a reduction in the diastolic expansion in the chambers. [6] This results in significant respiratory variation in blood flow in the chambers of the heart.[7]

During inspiration, pressure in the thoracic cavity decreases but is not relayed to the left atrium, subsequently a reduction in flow to the left atrium and ventricle happens. During diastole, less blood flow in left ventricle allows for more room for filling in right ventricle and therefore a septal shift occurs.[8]

During expiration, the amount of blood entering the left ventricle will increase, allowing the interventricular septum to bulge towards the right ventricle, decreasing the right heart ventricular filing.[9]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis is often difficult to make. In particular, restrictive cardiomyopathy has many similar clinical features to constrictive pericarditis, and differentiating them in a particular individual is often a diagnostic dilemma.[10]

- Chest X-Ray - pericardial calcification (common but not specific), pleural effusions are common findings.[11]

- Echocardiography - the principal echographic finding is changes in cardiac chamber volume.[11]

- CT and MRI - CT scan is useful in assessing the thickness of pericardium, calcification, and ventricular contour. Cardiac MRI may find pericardial thickening and pericardial-myocardial adherence. Ventricular septum shift during breathing can also be found using cardiac MRI. Late gadolinium enhancement can show enhancement of the pericardium due to fibroblast proliferation and neovascularization.[9]

- BNP blood test - tests for the existence of the cardiac hormone brain natriuretic peptide, which is only present in restrictive cardiomyopathy but not in constrictive pericarditis[12]

- Conventional cardiac catheterization[13]

- Physical examination - can reveal clinical features including Kussmaul's sign and a pericardial knock.[13]

Treatment

The definitive treatment for constrictive pericarditis is pericardial stripping, which is a surgical procedure where the entire pericardium is peeled away from the heart. This procedure has significant risk involved,[14] with mortality rates of 6% or higher in major referral centers.[15]

A poor outcome is almost always the result after a pericardiectomy is performed for constrictive pericarditis whose origin was radiation-induced, further some patients may develop heart failure post-operatively.[16]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Contrictive pericarditis". NIH. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001103.htm.

- ↑ Schwefer, Markus; Aschenbach, Rene; Heidemann, Jan; Mey, Celia; Lapp, Harald (September 2009). "Constrictive pericarditis, still a diagnostic challenge: comprehensive review of clinical management". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 36 (3): 502–510. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.03.004. PMID 19394850.

- ↑ Dunn, Brian (2013). Manual of cardiovascular medicine (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 653. ISBN 978-1-4511-3160-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=ruhJv1tM-CUC&q=tuberculosis+causes+constrictive+pericarditis&pg=PA653. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "Constritive pericarditis". MedScape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/157096-overview#showall.

- ↑ Lloyd, Joseph (2013). Mayo Clinic cardiology : concise textbook (4th ed.). Oxford: Mayo Clinic Scientific Press/Oxford University Press. p. 718. ISBN 978-0-199915712. https://books.google.com/books?id=WSCRAAAAQBAJ&q=pulmonary+asbestos++constrictive+pericarditis&pg=PA718. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Yadav NK, Siddique MS. Constrictive Pericarditis. [Updated 2022 May 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459314/

- ↑ Crouch, Michael A. (2010). Cardiovascular pharmacotherapy : a point-of-care guide. Bethesda, Md.: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. p. 376. ISBN 978-1-58528-215-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=U5MZBgAAQBAJ&q=constrictive+pericarditis+mechanism&pg=PT388. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Camm, Demosthenes G. Katritsis, Bernard J. Gersh, A. John (2013). Clinical cardiology : current practice guidelines (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-19-968528-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=1ZjrAQAAQBAJ&q=constrictive+pericarditis+definition&pg=PA388. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Welch, Terrence D.; Oh, Jae K. (November 2017). "Constrictive Pericarditis" (in en). Cardiology Clinics 35 (4): 539–549. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2017.07.007. PMID 29025545.

- ↑ "Restrictive pericarditis". MedScape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/153062-differential.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Imaging in Constrictive pericarditis". MedScape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/348883-overview.

- ↑ Semrad, Michal (2014). Cardiovascular Surgery. Charles University. p. 114. ISBN 978-80-246-2465-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=VaVxBgAAQBAJ&q=BNP+blood+test+constrictive+pericarditis&pg=PA114. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Khandaker, Masud H.; Espinosa, Raul E.; Nishimura, Rick A.; Sinak, Lawrence J.; Hayes, Sharonne N.; Melduni, Rowlens M.; Oh, Jae K. (June 2010). "Pericardial Disease: Diagnosis and Management". Mayo Clinic Proceedings 85 (6): 572–593. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0046. PMID 20511488.

- ↑ "Chronic constrictive tuberculous pericarditis: risk factors and outcome of pericardiectomy". Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 10 (6): 701–6. 2006. PMID 16776460.

- ↑ "Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: a clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic evaluation of two surgical techniques". Ann Thorac Surg 81 (2): 522–9. 2006. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.08.009. PMID 16427843.

- ↑ Greenberg, Barry H. (2007). Congestive heart failure (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 410. ISBN 978-0-7817-6285-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=PV8A8282d2EC&q=constrictive+pericarditis+treatment&pg=PA410. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

Further reading

- Hoit, B. D. (25 June 2002). "Management of Effusive and Constrictive Pericardial Heart Disease". Circulation 105 (25): 2939–2942. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000019421.07529.C5. PMID 12081983. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/105/25/2939.long. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

ja:心膜炎#慢性収縮性心膜炎

|