Physics:Uranium-235

Uranium metal highly enriched in uranium-235 | |

| General | |

|---|---|

| Symbol | 235U |

| Names | uranium-235, U-235 |

| Protons | 92 |

| Neutrons | 143 |

| Nuclide data | |

| Natural abundance | 0.72% |

| Half-life | 703800000 years |

| Parent isotopes | 235Pa 235Np 239Pu |

| Decay products | 231Th |

| Isotope mass | 235.0439299 u |

| Spin | 7/2− |

| Excess energy | 40914.062±1.970 keV |

| Binding energy | 1783870.285±1.996 keV |

| Decay modes | |

| Decay mode | Decay energy (MeV) |

| Alpha | 4.679 |

| Isotopes of Chemistry:uranium Complete table of nuclides | |

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nature as a primordial nuclide.

Uranium-235 has a half-life of 703.8 million years. It was discovered in 1935 by Arthur Jeffrey Dempster. Its fission cross section for slow thermal neutrons is about 584.3±1 barns.[1] For fast neutrons it is on the order of 1 barn.[2] Most neutron absorptions induce fission, though a minority result in the formation of uranium-236.[citation needed]

Fission properties

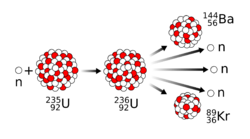

The fission of one atom of uranium-235 releases 202.5 MeV (3.24×10−11 J) inside the reactor. That corresponds to 19.54 TJ/mol, or 83.14 TJ/kg.[3] Another 8.8 MeV escapes the reactor as anti-neutrinos. When 23592U nuclei are bombarded with neutrons, one of the many fission reactions that it can undergo is the following (shown in the adjacent image):

Heavy water reactors and some graphite moderated reactors can use natural uranium, but light water reactors must use low enriched uranium because of the higher neutron absorption of light water. Uranium enrichment removes some of the uranium-238 and increases the proportion of uranium-235. Highly enriched uranium (HEU), which contains an even greater proportion of uranium-235, is sometimes used in the reactors of nuclear submarines, research reactors and nuclear weapons.

If at least one neutron from uranium-235 fission strikes another nucleus and causes it to fission, then the chain reaction will continue. If the reaction continues to sustain itself, it is said to be critical, and the mass of 235U required to produce the critical condition is said to be a critical mass. A critical chain reaction can be achieved at low concentrations of 235U if the neutrons from fission are moderated to lower their speed, since the probability for fission with slow neutrons is greater. A fission chain reaction produces intermediate mass fragments which are highly radioactive and produce further energy by their radioactive decay. Some of them produce neutrons, called delayed neutrons, which contribute to the fission chain reaction. The power output of nuclear reactors is adjusted by the location of control rods containing elements that strongly absorb neutrons, e.g., boron, cadmium, or hafnium, in the reactor core. In nuclear bombs, the reaction is uncontrolled and the large amount of energy released creates a nuclear explosion.

Nuclear weapons

The Little Boy gun-type atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, was made of highly enriched uranium with a large tamper. The nominal spherical critical mass for an untampered 235U nuclear weapon is 56 kilograms (123 lb),[4] which would form a sphere 17.32 centimetres (6.82 in) in diameter. The material must be 85% or more of 235U and is known as weapons grade uranium, though for a crude and inefficient weapon 20% enrichment is sufficient (called weapon(s)-usable). Even lower enrichment can be used, but this results in the required critical mass rapidly increasing. Use of a large tamper, implosion geometries, trigger tubes, polonium triggers, tritium enhancement, and neutron reflectors can enable a more compact, economical weapon using one-fourth or less of the nominal critical mass, though this would likely only be possible in a country that already had extensive experience in engineering nuclear weapons. Most modern nuclear weapon designs use plutonium-239 as the fissile component of the primary stage;[5][6] however, HEU (highly enriched uranium, in this case uranium that is 20% or more 235U) is frequently used in the secondary stage as an ignitor for the fusion fuel.

| Source | Average energy released [MeV][3] |

|---|---|

| Instantaneously released energy | |

| Kinetic energy of fission fragments | 169.1 |

| Kinetic energy of prompt neutrons | 4.8 |

| Energy carried by prompt γ-rays | 7.0 |

| Energy from decaying fission products | |

| Energy of β− particles | 6.5 |

| Energy of delayed γ-rays | 6.3 |

| Energy released when those prompt neutrons which do not (re)produce fission are captured | 8.8 |

| Total energy converted into heat in an operating thermal nuclear reactor | 202.5 |

| Energy of anti-neutrinos | 8.8 |

| Sum | 211.3 |

Natural decay chain

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{r} \ce{^{235}_{92}U -\gt [\alpha][7.038 \times 10^8 \ \ce y] {^{231}_{90}Th} -\gt [\beta^-][25.52 \ \ce h] {^{231}_{91}Pa} -\gt [\alpha][3.276 \times 10^4 \ \ce y] {^{227}_{89}Ac}} \begin{Bmatrix} \ce{-\gt [98.62\% \beta^-][21.773 \ \ce y] {^{227}_{90}Th} -\gt [\alpha][18.718 \ \ce d]} \\ \ce{-\gt [1.38\% \alpha][21.773 \ \ce y] {^{223}_{87}Fr} -\gt [\beta^-][21.8 \ \ce{min}]} \end{Bmatrix} \ce{^{223}_{88}Ra -\gt [\alpha][11.434 \ \ce d] {^{219}_{86}Rn}} \\ \ce{^{219}_{86}Rn -\gt [\alpha][3.96 \ \ce s] {^{215}_{84}Po}} \begin{Bmatrix} \ce{-\gt [99.99\% \alpha][1.778 \ \ce{ms}] {^{211}_{82}Pb} -\gt [\beta^-][36.1 \ \ce{min}]} \\ \ce{-\gt [2.3\times 10^{-4}\% \beta^-][1.778 \ \ce{ms}] {^{215}_{85}At} -\gt [\alpha][0.10 \ \ce{ms}]} \end{Bmatrix} \ce{^{211}_{83}Bi} \begin{Bmatrix} \ce{-\gt [99.73\% \alpha][2.13 \ \ce{min}] {^{207}_{81}Tl} -\gt [\beta^-][4.77 \ \ce{min}]} \\ \ce{-\gt [0.27\% \beta^-][2.13 \ \ce{min}] {^{211}_{84}Po} -\gt [\alpha][0.516 \ \ce s]} \end{Bmatrix} \ce{^{207}_{82}Pb_{(stable)}} \end{array} }[/math]

Uses

Uranium-235 has many uses such as fuel for nuclear power plants and in nuclear weapons such as nuclear bombs. Some artificial satellites, such as the SNAP-10A and the RORSATs were powered by nuclear reactors fueled with uranium-235.[7][8]

References

- ↑ "#Standard Reaction: 235U(n,f)". IAEA. https://www-nds.iaea.org/standards/Data/standards-235U_xs-data.txt.

- ↑ ""Some Physics of Uranium", UIC.com.au". http://www.uic.com.au/uicphys.htm.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nuclear fission and fusion, and neutron interactions, National Physical Laboratory Archive.

- ↑ "FAS Nuclear Weapons Design FAQ". https://fas.org/nuke/intro/nuke/design.htm.

- ↑ Nuclear Weapon Design. Federation of American Scientists. https://fas.org/nuke/intro/nuke/design.htm. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- ↑ Miner, William N.; Schonfeld, Fred W. (1968). "Plutonium". in Clifford A. Hampel. The Encyclopedia of the Chemical Elements. New York (NY): Reinhold Book Corporation. p. 541. https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofch00hamp.

- ↑ Schmidt, Glen (February 2011). "SNAP Overview – radium-219 – general background". American Nuclear Society. http://anstd.ans.org/NETS2011/Documents/Presentations/Opening%20Dinner%20SNAP%2010A%20Schmidt.pdf.

- ↑ "RORSAT (Radar Ocean Reconnaissance Satellite)". daviddarling.info. http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/R/RORSAT.html.

External links

- Table of Nuclides.

- DOE Fundamentals handbook: Nuclear Physics and Reactor theory Vol. 1 , Vol. 2 .

- Radionuclide Basics: Uranium |US EPA

- NLM Hazardous Substances Databank – Uranium, Radioactive

- "The Miracle of U-235", Popular Mechanics, January 1941—one of the earliest articles on U-235 for the general public

| Lighter: uranium-234 |

Uranium-235 is an isotope of uranium |

Heavier: uranium-236 |

| Decay product of: protactinium-235 neptunium-235 plutonium-239 |

Decay chain of uranium-235 |

Decays to: thorium-231 |

|