Physics:Radioactive decay

| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

| Nucleus · Nucleons (p, n) · Nuclear matter · Nuclear force · Nuclear structure · Nuclear reaction |

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is considered radioactive. Three of the most common types of decay are alpha, beta, and gamma decay. The weak force is the mechanism that is responsible for beta decay, while the other two are governed by the electromagnetism and nuclear force.[1]

Radioactive decay is a stochastic (i.e., random) process at the level of single atoms. According to quantum theory, it is impossible to predict when a particular atom will decay, regardless of how long the atom has existed.[2][3][4] However, for a significant number of identical atoms, the overall decay rate can be expressed as a decay constant or as half-life. The half-lives of radioactive atoms have a huge range; from nearly instantaneous to far longer than the age of the universe.

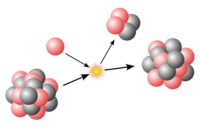

The decaying nucleus is called the parent radionuclide (or parent radioisotope[note 1]), and the process produces at least one daughter nuclide. Except for gamma decay or internal conversion from a nuclear excited state, the decay is a nuclear transmutation resulting in a daughter containing a different number of protons or neutrons (or both). When the number of protons changes, an atom of a different chemical element is created.

There are 28 naturally occurring chemical elements on Earth that are radioactive, consisting of 34 radionuclides (six elements have two different radionuclides) that date before the time of formation of the Solar System. These 34 are known as primordial nuclides. Well-known examples are uranium and thorium, but also included are naturally occurring long-lived radioisotopes, such as potassium-40.

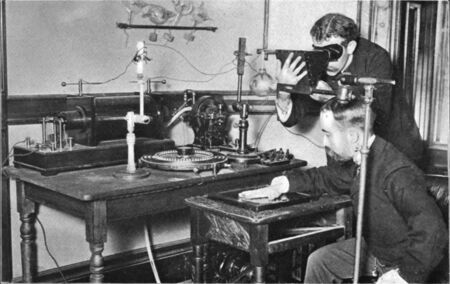

History of discovery

Radioactivity was discovered in 1896 by scientists Henri Becquerel and Marie Skłodowska-Curie, while working with phosphorescent materials.[5][6][7][8][9] These materials glow in the dark after exposure to light, and Becquerel suspected that the glow produced in cathode ray tubes by X-rays might be associated with phosphorescence. He wrapped a photographic plate in black paper and placed various phosphorescent salts on it. All results were negative until he used uranium salts. The uranium salts caused a blackening of the plate in spite of the plate being wrapped in black paper. These radiations were given the name "Becquerel Rays".

It soon became clear that the blackening of the plate had nothing to do with phosphorescence, as the blackening was also produced by non-phosphorescent salts of uranium and by metallic uranium. It became clear from these experiments that there was a form of invisible radiation that could pass through paper and was causing the plate to react as if exposed to light.

At first, it seemed as though the new radiation was similar to the then recently discovered X-rays. Further research by Becquerel, Ernest Rutherford, Paul Villard, Pierre Curie, Marie Curie, and others showed that this form of radioactivity was significantly more complicated. Rutherford was the first to realize that all such elements decay in accordance with the same mathematical exponential formula. Rutherford and his student Frederick Soddy were the first to realize that many decay processes resulted in the transmutation of one element to another. Subsequently, the radioactive displacement law of Fajans and Soddy was formulated to describe the products of alpha and beta decay.[10][11]

The early researchers also discovered that many other chemical elements, besides uranium, have radioactive isotopes. A systematic search for the total radioactivity in uranium ores also guided Pierre and Marie Curie to isolate two new elements: polonium and radium. Except for the radioactivity of radium, the chemical similarity of radium to barium made these two elements difficult to distinguish.

Marie and Pierre Curie's study of radioactivity is an important factor in science and medicine. After their research on Becquerel's rays led them to the discovery of both radium and polonium, they coined the term "radioactivity"[12] to define the emission of ionizing radiation by some heavy elements.[13] (Later the term was generalized to all elements.) Their research on the penetrating rays in uranium and the discovery of radium launched an era of using radium for the treatment of cancer. Their exploration of radium could be seen as the first peaceful use of nuclear energy and the start of modern nuclear medicine.[12]

Early health dangers

The dangers of ionizing radiation due to radioactivity and X-rays were not immediately recognized.

X-rays

The discovery of X‑rays by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895 led to widespread experimentation by scientists, physicians, and inventors. Many people began recounting stories of burns, hair loss and worse in technical journals as early as 1896. In February of that year, Professor Daniel and Dr. Dudley of Vanderbilt University performed an experiment involving X-raying Dudley's head that resulted in his hair loss. A report by Dr. H.D. Hawks, of his suffering severe hand and chest burns in an X-ray demonstration, was the first of many other reports in Electrical Review.[14]

Other experimenters, including Elihu Thomson and Nikola Tesla, also reported burns. Thomson deliberately exposed a finger to an X-ray tube over a period of time and suffered pain, swelling, and blistering.[15] Other effects, including ultraviolet rays and ozone, were sometimes blamed for the damage,[16] and many physicians still claimed that there were no effects from X-ray exposure at all.[15]

Despite this, there were some early systematic hazard investigations, and as early as 1902 William Herbert Rollins wrote almost despairingly that his warnings about the dangers involved in the careless use of X-rays were not being heeded, either by industry or by his colleagues. By this time, Rollins had proved that X-rays could kill experimental animals, could cause a pregnant guinea pig to abort, and that they could kill a foetus. He also stressed that "animals vary in susceptibility to the external action of X-light" and warned that these differences be considered when patients were treated by means of X-rays.[citation needed]

Radioactive substances

However, the biological effects of radiation due to radioactive substances were less easy to gauge. This gave the opportunity for many physicians and corporations to market radioactive substances as patent medicines. Examples were radium enema treatments, and radium-containing waters to be drunk as tonics. Marie Curie protested against this sort of treatment, warning that "radium is dangerous in untrained hands".[17] Curie later died from aplastic anaemia, likely caused by exposure to ionizing radiation. By the 1930s, after a number of cases of bone necrosis and death of radium treatment enthusiasts, radium-containing medicinal products had been largely removed from the market (radioactive quackery).

Radiation protection

Only a year after Röntgen's discovery of X rays, the American engineer Wolfram Fuchs (1896) gave what is probably the first protection advice, but it was not until 1925 that the first International Congress of Radiology (ICR) was held and considered establishing international protection standards. The effects of radiation on genes, including the effect of cancer risk, were recognized much later. In 1927, Hermann Joseph Muller published research showing genetic effects and, in 1946, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his findings.

The second ICR was held in Stockholm in 1928 and proposed the adoption of the röntgen unit, and the International X-ray and Radium Protection Committee (IXRPC) was formed. Rolf Sievert was named chairman, but a driving force was George Kaye of the British National Physical Laboratory. The committee met in 1931, 1934, and 1937.

After World War II, the increased range and quantity of radioactive substances being handled as a result of military and civil nuclear programs led to large groups of occupational workers and the public being potentially exposed to harmful levels of ionising radiation. This was considered at the first post-war ICR convened in London in 1950, when the present International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) was born.[18] Since then the ICRP has developed the present international system of radiation protection, covering all aspects of radiation hazards.

In 2020, Hauptmann and other 15 international researchers of eight nations, among which: Institutes of Biostatistics, Registry Research, Centers of Cancer Epidemiology, Radiation Epidemiology, and then also U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI), International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and Radiation Effects Research Foundation of Hiroshima studied definitively through meta-analysis the damage resulting from the "low doses" that have afflicted the populations of survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and also in numerous accidents of nuclear plants that have occurred in the world. These scientists reported, in JNCI Monographs: Epidemiological Studies of Low Dose Ionizing Radiation and Cancer Risk, that the new epidemiological studies directly support excess cancer risks from low-dose ionizing radiation.[19] In 2021, Italian researcher Venturi reported the first correlations between radio-caesium and pancreatic cancer with the role of caesium in biology and in pancreatitis and in diabetes of pancreatic origin.[20]

Units

The International System of Units (SI) unit of radioactive activity is the becquerel (Bq), named in honor of the scientist Henri Becquerel. One Bq is defined as one transformation (or decay or disintegration) per second.

An older unit of radioactivity is the curie, Ci, which was originally defined as "the quantity or mass of radium emanation in equilibrium with one gram of radium (element)".[21] Today, the curie is defined as 3.7×1010 disintegrations per second, so that 1 curie (Ci) = 3.7×1010 Bq. For radiological protection purposes, although the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission permits the use of the unit curie alongside SI units,[22] the European Union European units of measurement directives required that its use for "public health ... purposes" be phased out by 31 December 1985.[23]

The effects of ionizing radiation are often measured in units of gray for mechanical or sievert for damage to tissue.

Types

Radioactive decay results in a reduction of summed rest mass, once the released energy (the disintegration energy) has escaped in some way. Although decay energy is sometimes defined as associated with the difference between the mass of the parent nuclide products and the mass of the decay products, this is true only of rest mass measurements, where some energy has been removed from the product system. This is true because the decay energy must always carry mass with it, wherever it appears (see mass in special relativity) according to the formula E = mc2. The decay energy is initially released as the energy of emitted photons plus the kinetic energy of massive emitted particles (that is, particles that have rest mass). If these particles come to thermal equilibrium with their surroundings and photons are absorbed, then the decay energy is transformed to thermal energy, which retains its mass.

Decay energy, therefore, remains associated with a certain measure of the mass of the decay system, called invariant mass, which does not change during the decay, even though the energy of decay is distributed among decay particles. The energy of photons, the kinetic energy of emitted particles, and, later, the thermal energy of the surrounding matter, all contribute to the invariant mass of the system. Thus, while the sum of the rest masses of the particles is not conserved in radioactive decay, the system mass and system invariant mass (and also the system total energy) is conserved throughout any decay process. This is a restatement of the equivalent laws of conservation of energy and conservation of mass.

Alpha, beta and gamma decay

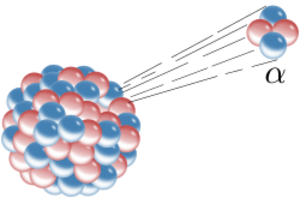

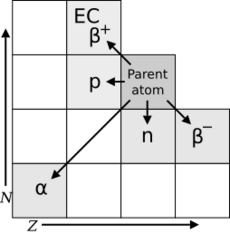

Early researchers found that an electric or magnetic field could split radioactive emissions into three types of beams. The rays were given the names alpha, beta, and gamma, in increasing order of their ability to penetrate matter. Alpha decay is observed only in heavier elements of atomic number 52 (tellurium) and greater, with the exception of beryllium-8 (which decays to two alpha particles). The other two types of decay are observed in all the elements. Lead, atomic number 82, is the heaviest element to have any isotopes stable (to the limit of measurement) to radioactive decay. Radioactive decay is seen in all isotopes of all elements of atomic number 83 (bismuth) or greater. Bismuth-209, however, is only very slightly radioactive, with a half-life greater than the age of the universe; radioisotopes with extremely long half-lives are considered effectively stable for practical purposes.

In analysing the nature of the decay products, it was obvious from the direction of the electromagnetic forces applied to the radiations by external magnetic and electric fields that alpha particles carried a positive charge, beta particles carried a negative charge, and gamma rays were neutral. From the magnitude of deflection, it was clear that alpha particles were much more massive than beta particles. Passing alpha particles through a very thin glass window and trapping them in a discharge tube allowed researchers to study the emission spectrum of the captured particles, and ultimately proved that alpha particles are helium nuclei. Other experiments showed beta radiation, resulting from decay and cathode rays, were high-speed electrons. Likewise, gamma radiation and X-rays were found to be high-energy electromagnetic radiation.

The relationship between the types of decays also began to be examined: For example, gamma decay was almost always found to be associated with other types of decay, and occurred at about the same time, or afterwards. Gamma decay as a separate phenomenon, with its own half-life (now termed isomeric transition), was found in natural radioactivity to be a result of the gamma decay of excited metastable nuclear isomers, which were in turn created from other types of decay. Although alpha, beta, and gamma radiations were most commonly found, other types of emission were eventually discovered. Shortly after the discovery of the positron in cosmic ray products, it was realized that the same process that operates in classical beta decay can also produce positrons (positron emission), along with neutrinos (classical beta decay produces antineutrinos).

Electron capture

In electron capture, some proton-rich nuclides were found to capture their own atomic electrons instead of emitting positrons, and subsequently, these nuclides emit only a neutrino and a gamma ray from the excited nucleus (and often also Auger electrons and characteristic X-rays, as a result of the re-ordering of electrons to fill the place of the missing captured electron). These types of decay involve the nuclear capture of electrons or emission of electrons or positrons, and thus acts to move a nucleus toward the ratio of neutrons to protons that has the least energy for a given total number of nucleons. This consequently produces a more stable (lower energy) nucleus.

A hypothetical process of positron capture, analogous to electron capture, is theoretically possible in antimatter atoms, but has not been observed, as complex antimatter atoms beyond antihelium are not experimentally available.[24] Such a decay would require antimatter atoms at least as complex as beryllium-7, which is the lightest known isotope of normal matter to undergo decay by electron capture.[25]

Nucleon emission

Shortly after the discovery of the neutron in 1932, Enrico Fermi realized that certain rare beta-decay reactions immediately yield neutrons as an additional decay particle, so called beta-delayed neutron emission. Neutron emission usually happens from nuclei that are in an excited state, such as the excited 17O* produced from the beta decay of 17N. The neutron emission process itself is controlled by the nuclear force and therefore is extremely fast, sometimes referred to as "nearly instantaneous". Isolated proton emission was eventually observed in some elements. It was also found that some heavy elements may undergo spontaneous fission into products that vary in composition. In a phenomenon called cluster decay, specific combinations of neutrons and protons other than alpha particles (helium nuclei) were found to be spontaneously emitted from atoms.

More exotic types of decay

Other types of radioactive decay were found to emit previously seen particles but via different mechanisms. An example is internal conversion, which results in an initial electron emission, and then often further characteristic X-rays and Auger electrons emissions, although the internal conversion process involves neither beta nor gamma decay. A neutrino is not emitted, and none of the electron(s) and photon(s) emitted originate in the nucleus, even though the energy to emit all of them does originate there. Internal conversion decay, like isomeric transition gamma decay and neutron emission, involves the release of energy by an excited nuclide, without the transmutation of one element into another.

Rare events that involve a combination of two beta-decay-type events happening simultaneously are known (see below). Any decay process that does not violate the conservation of energy or momentum laws (and perhaps other particle conservation laws) is permitted to happen, although not all have been detected. An interesting example discussed in a final section, is bound state beta decay of rhenium-187. In this process, the beta electron-decay of the parent nuclide is not accompanied by beta electron emission, because the beta particle has been captured into the K-shell of the emitting atom. An antineutrino is emitted, as in all negative beta decays.

If energy circumstances are favorable, a given radionuclide may undergo many competing types of decay, with some atoms decaying by one route, and others decaying by another. An example is copper-64, which has 29 protons, and 35 neutrons, which decays with a half-life of 12.7004(13) hours.[26] This isotope has one unpaired proton and one unpaired neutron, so either the proton or the neutron can decay to the other particle, which has opposite isospin. This particular nuclide (though not all nuclides in this situation) is more likely to decay through beta plus decay (61.52(26)%[26]) than through electron capture (38.48(26)%[26]). The excited energy states resulting from these decays which fail to end in a ground energy state, also produce later internal conversion and gamma decay in almost 0.5% of the time.

List of decay modes

Decay chains and multiple modes

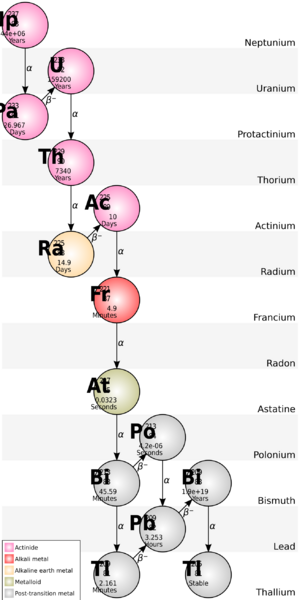

The daughter nuclide of a decay event may also be unstable (radioactive). In this case, it too will decay, producing radiation. The resulting second daughter nuclide may also be radioactive. This can lead to a sequence of several decay events called a decay chain (see this article for specific details of important natural decay chains). Eventually, a stable nuclide is produced. Any decay daughters that are the result of an alpha decay will also result in helium atoms being created.

Some radionuclides may have several different paths of decay. For example, 35.94(6)%[26] of bismuth-212 decays, through alpha-emission, to thallium-208 while 64.06(6)%[26] of bismuth-212 decays, through beta-emission, to polonium-212. Both thallium-208 and polonium-212 are radioactive daughter products of bismuth-212, and both decay directly to stable lead-208.

Occurrence and applications

According to the Big Bang theory, stable isotopes of the lightest three elements (H, He, and traces of Li) were produced very shortly after the emergence of the universe, in a process called Big Bang nucleosynthesis. These lightest stable nuclides (including deuterium) survive to today, but any radioactive isotopes of the light elements produced in the Big Bang (such as tritium) have long since decayed. Isotopes of elements heavier than boron were not produced at all in the Big Bang, and these first five elements do not have any long-lived radioisotopes. Thus, all radioactive nuclei are, therefore, relatively young with respect to the birth of the universe, having formed later in various other types of nucleosynthesis in stars (in particular, supernovae), and also during ongoing interactions between stable isotopes and energetic particles. For example, carbon-14, a radioactive nuclide with a half-life of only 5700(30) years,[26] is constantly produced in Earth's upper atmosphere due to interactions between cosmic rays and nitrogen.

Nuclides that are produced by radioactive decay are called radiogenic nuclides, whether they themselves are stable or not. There exist stable radiogenic nuclides that were formed from short-lived extinct radionuclides in the early Solar System.[28][29] The extra presence of these stable radiogenic nuclides (such as xenon-129 from extinct iodine-129) against the background of primordial stable nuclides can be inferred by various means.

Radioactive decay has been put to use in the technique of radioisotopic labeling, which is used to track the passage of a chemical substance through a complex system (such as a living organism). A sample of the substance is synthesized with a high concentration of unstable atoms. The presence of the substance in one or another part of the system is determined by detecting the locations of decay events.

On the premise that radioactive decay is truly random (rather than merely chaotic), it has been used in hardware random-number generators. Because the process is not thought to vary significantly in mechanism over time, it is also a valuable tool in estimating the absolute ages of certain materials. For geological materials, the radioisotopes and some of their decay products become trapped when a rock solidifies, and can then later be used (subject to many well-known qualifications) to estimate the date of the solidification. These include checking the results of several simultaneous processes and their products against each other, within the same sample. In a similar fashion, and also subject to qualification, the rate of formation of carbon-14 in various eras, the date of formation of organic matter within a certain period related to the isotope's half-life may be estimated, because the carbon-14 becomes trapped when the organic matter grows and incorporates the new carbon-14 from the air. Thereafter, the amount of carbon-14 in organic matter decreases according to decay processes that may also be independently cross-checked by other means (such as checking the carbon-14 in individual tree rings, for example).

Szilard–Chalmers effect

The Szilard–Chalmers effect is the breaking of a chemical bond as a result of a kinetic energy imparted from radioactive decay. It operates by the absorption of neutrons by an atom and subsequent emission of gamma rays, often with significant amounts of kinetic energy. This kinetic energy, by Newton's third law, pushes back on the decaying atom, which causes it to move with enough speed to break a chemical bond.[30] This effect can be used to separate isotopes by chemical means.

The Szilard–Chalmers effect was discovered in 1934 by Leó Szilárd and Thomas A. Chalmers.[31] They observed that after bombardment by neutrons, the breaking of a bond in liquid ethyl iodide allowed radioactive iodine to be removed.[32]

Origins of radioactive nuclides

Radioactive primordial nuclides found in the Earth are residues from ancient supernova explosions that occurred before the formation of the Solar System. They are the fraction of radionuclides that survived from that time, through the formation of the primordial solar nebula, through planet accretion, and up to the present time. The naturally occurring short-lived radiogenic radionuclides found in today's rocks, are the daughters of those radioactive primordial nuclides. Another minor source of naturally occurring radioactive nuclides are cosmogenic nuclides, that are formed by cosmic ray bombardment of material in the Earth's atmosphere or crust. The decay of the radionuclides in rocks of the Earth's mantle and crust contribute significantly to Earth's internal heat budget.

Rates

The decay rate, or activity, of a radioactive substance is characterized by the following time-independent parameters:

- The half-life, t1/2, is the time taken for the activity of a given amount of a radioactive substance to decay to half of its initial value.

- The decay constant, λ "lambda", the reciprocal of the mean lifetime (in s−1), sometimes referred to as simply decay rate.

- The mean lifetime, τ "tau", the average lifetime (1/e life) of a radioactive particle before decay.

Although these are constants, they are associated with the statistical behavior of populations of atoms. In consequence, predictions using these constants are less accurate for minuscule samples of atoms.

In principle a half-life, a third-life, or even a (1/√2)-life, can be used in exactly the same way as half-life; but the mean life and half-life t1/2 have been adopted as standard times associated with exponential decay.

Those parameters can be related to the following time-dependent parameters:

- Total activity (or just activity), A, is the number of decays per unit time of a radioactive sample.

- Number of particles, N, in the sample.

- Specific activity, a, is the number of decays per unit time per amount of substance of the sample at time set to zero (t = 0). "Amount of substance" can be the mass, volume or moles of the initial sample.

These are related as follows:

where N0 is the initial amount of active substance — substance that has the same percentage of unstable particles as when the substance was formed.

Mathematics

Universal law

The mathematics of radioactive decay depend on a key assumption that a nucleus of a radionuclide has no "memory" or way of translating its history into its present behavior. A nucleus does not "age" with the passage of time. Thus, the probability of its breaking down does not increase with time but stays constant, no matter how long the nucleus has existed. This constant probability may differ greatly between one type of nucleus and another, leading to the many different observed decay rates. However, whatever the probability is, it does not change over time. This is in marked contrast to complex objects that do show aging, such as automobiles and humans. These aging systems do have a chance of breakdown per unit of time that increases from the moment they begin their existence.

Aggregate processes, like the radioactive decay of a lump of atoms, for which the single-event probability of realization is very small but in which the number of time-slices is so large that there is nevertheless a reasonable rate of events, are modelled by the Poisson distribution, which is discrete. Radioactive decay and nuclear particle reactions are two examples of such aggregate processes.[33] The mathematics of Poisson processes reduce to the law of exponential decay, which describes the statistical behaviour of a large number of nuclei, rather than one individual nucleus. In the following formalism, the number of nuclei or the nuclei population N, is of course a discrete variable (a natural number)—but for any physical sample N is so large that it can be treated as a continuous variable. Differential calculus is used to model the behaviour of nuclear decay.

One-decay process

Consider the case of a nuclide A that decays into another B by some process A → B (emission of other particles, like electron neutrinos νe and electrons e− as in beta decay, are irrelevant in what follows). The decay of an unstable nucleus is entirely random in time so it is impossible to predict when a particular atom will decay. However, it is equally likely to decay at any instant in time. Therefore, given a sample of a particular radioisotope, the number of decay events −dN expected to occur in a small interval of time dt is proportional to the number of atoms present N, that is[34]

Particular radionuclides decay at different rates, so each has its own decay constant λ. The expected decay −dN/N is proportional to an increment of time, dt:

The negative sign indicates that N decreases as time increases, as the decay events follow one after another. The solution to this first-order differential equation is the function:

where N0 is the value of N at time t = 0, with the decay constant expressed as λ[34]

We have for all time t:

where Ntotal is the constant number of particles throughout the decay process, which is equal to the initial number of A nuclides since this is the initial substance.

If the number of non-decayed A nuclei is:

then the number of nuclei of B (i.e. the number of decayed A nuclei) is

The number of decays observed over a given interval obeys Poisson statistics. If the average number of decays is ⟨N⟩, the probability of a given number of decays N is[34]

Chain-decay processes

Chain of two decays

Now consider the case of a chain of two decays: one nuclide A decaying into another B by one process, then B decaying into another C by a second process, i.e. A → B → C. The previous equation cannot be applied to the decay chain, but can be generalized as follows. Since A decays into B, then B decays into C, the activity of A adds to the total number of B nuclides in the present sample, before those B nuclides decay and reduce the number of nuclides leading to the later sample. In other words, the number of second generation nuclei B increases as a result of the first generation nuclei decay of A, and decreases as a result of its own decay into the third generation nuclei C.[35] The sum of these two terms gives the law for a decay chain for two nuclides:

The rate of change of NB, that is dNB/dt, is related to the changes in the amounts of A and B, NB can increase as B is produced from A and decrease as B produces C.

Re-writing using the previous results:

The subscripts simply refer to the respective nuclides, i.e. NA is the number of nuclides of type A; NA0 is the initial number of nuclides of type A; λA is the decay constant for A – and similarly for nuclide B. Solving this equation for NB gives:

In the case where B is a stable nuclide (λB = 0), this equation reduces to the previous solution:

as shown above for one decay. The solution can be found by the integration factor method, where the integrating factor is eλBt. This case is perhaps the most useful since it can derive both the one-decay equation (above) and the equation for multi-decay chains (below) more directly.

Chain of any number of decays

For the general case of any number of consecutive decays in a decay chain, i.e. A1 → A2 ··· → Ai ··· → AD, where D is the number of decays and i is a dummy index (i = 1, 2, 3, ...D), each nuclide population can be found in terms of the previous population. In this case N2 = 0, N3 = 0, ..., ND = 0. Using the above result in a recursive form:

The general solution to the recursive problem is given by Bateman's equations:[36]

Alternative modes

In all of the above examples, the initial nuclide decays into just one product.[37] Consider the case of one initial nuclide that can decay into either of two products, that is A → B and A → C in parallel. For example, in a sample of potassium-40, 89.3% of the nuclei decay to calcium-40 and 10.7% to argon-40. We have for all time t:

which is constant, since the total number of nuclides remains constant. Differentiating with respect to time:

defining the total decay constant λ in terms of the sum of partial decay constants λB and λC:

Solving this equation for NA:

where NA0 is the initial number of nuclide A. When measuring the production of one nuclide, one can only observe the total decay constant λ. The decay constants λB and λC determine the probability for the decay to result in products B or C as follows:

because the fraction λB/λ of nuclei decay into B while the fraction λC/λ of nuclei decay into C.

Corollaries of laws

The above equations can also be written using quantities related to the number of nuclide particles N in a sample;

- The activity: A = λN.

- The amount of substance: n = N/NA.

- The mass: m = Mn = MN/NA.

where NA = 6.02214076×1023 mol−1[38] is the Avogadro constant, M is the molar mass of the substance in kg/mol, and the amount of the substance n is in moles.

Decay timing: definitions and relations

Time constant and mean-life

For the one-decay solution A → B:

the equation indicates that the decay constant λ has units of t−1, and can thus also be represented as 1/τ, where τ is a characteristic time of the process called the time constant.

In a radioactive decay process, this time constant is also the mean lifetime for decaying atoms. Each atom "lives" for a finite amount of time before it decays, and it may be shown that this mean lifetime is the arithmetic mean of all the atoms' lifetimes, and that it is τ, which again is related to the decay constant as follows:

This form is also true for two-decay processes simultaneously A → B + C, inserting the equivalent values of decay constants (as given above)

into the decay solution leads to:

Half-life

A more commonly used parameter is the half-life T1/2. Given a sample of a particular radionuclide, the half-life is the time taken for half the radionuclide's atoms to decay. For the case of one-decay nuclear reactions:

the half-life is related to the decay constant as follows: set N = N0/2 and t = T1/2 to obtain

This relationship between the half-life and the decay constant shows that highly radioactive substances are quickly spent, while those that radiate weakly endure longer. Half-lives of known radionuclides vary by almost 54 orders of magnitude, from more than 2.25(9)×1024 years (6.9×1031 sec) for the very nearly stable nuclide 128Te, to 8.6(6)×10−23 seconds for the highly unstable nuclide 5H.[26]

The factor of ln(2) in the above relations results from the fact that the concept of "half-life" is merely a way of selecting a different base other than the natural base e for the lifetime expression. The time constant τ is the e −1 -life, the time until only 1/e remains, about 36.8%, rather than the 50% in the half-life of a radionuclide. Thus, τ is longer than t1/2. The following equation can be shown to be valid:

Since radioactive decay is exponential with a constant probability, each process could as easily be described with a different constant time period that (for example) gave its "(1/3)-life" (how long until only 1/3 is left) or "(1/10)-life" (a time period until only 10% is left), and so on. Thus, the choice of τ and t1/2 for marker-times, are only for convenience, and from convention. They reflect a fundamental principle only in so much as they show that the same proportion of a given radioactive substance will decay, during any time-period that one chooses.

Mathematically, the nth life for the above situation would be found in the same way as above—by setting N = N0/n, t = T1/n and substituting into the decay solution to obtain

Example for carbon-14

Carbon-14 has a half-life of 5700(30) years[26] and a decay rate of 14 disintegrations per minute (dpm) per gram of natural carbon.

If an artifact is found to have radioactivity of 4 dpm per gram of its present C, we can find the approximate age of the object using the above equation:

where:

Changing rates

The radioactive decay modes of electron capture and internal conversion are known to be slightly sensitive to chemical and environmental effects that change the electronic structure of the atom, which in turn affects the presence of 1s and 2s electrons that participate in the decay process. A small number of nuclides are affected.[39] For example, chemical bonds can affect the rate of electron capture to a small degree (in general, less than 1%) depending on the proximity of electrons to the nucleus. In 7Be, a difference of 0.9% has been observed between half-lives in metallic and insulating environments.[40] This relatively large effect is because beryllium is a small atom whose valence electrons are in 2s atomic orbitals, which are subject to electron capture in 7Be because (like all s atomic orbitals in all atoms) they naturally penetrate into the nucleus.

In 1992, Jung et al. of the Darmstadt Heavy-Ion Research group observed an accelerated β− decay of 163Dy66+. Although neutral 163Dy is a stable isotope, the fully ionized 163Dy66+ undergoes β− decay into the K and L shells to 163Ho66+ with a half-life of 47 days.[41]

Rhenium-187 is another spectacular example. 187Re normally undergoes beta decay to 187Os with a half-life of 41.6 × 109 years,[42] but studies using fully ionised 187Re atoms (bare nuclei) have found that this can decrease to only 32.9 years.[43] This is attributed to "bound-state β− decay" of the fully ionised atom – the electron is emitted into the "K-shell" (1s atomic orbital), which cannot occur for neutral atoms in which all low-lying bound states are occupied.[44]

A number of experiments have found that decay rates of other modes of artificial and naturally occurring radioisotopes are, to a high degree of precision, unaffected by external conditions such as temperature, pressure, the chemical environment, and electric, magnetic, or gravitational fields.[45] Comparison of laboratory experiments over the last century, studies of the Oklo natural nuclear reactor (which exemplified the effects of thermal neutrons on nuclear decay), and astrophysical observations of the luminosity decays of distant supernovae (which occurred far away so the light has taken a great deal of time to reach us), for example, strongly indicate that unperturbed decay rates have been constant (at least to within the limitations of small experimental errors) as a function of time as well.[citation needed]

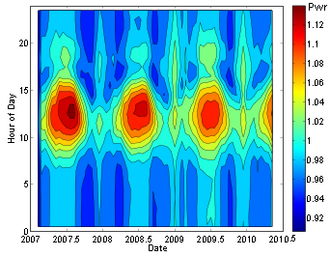

Recent results suggest the possibility that decay rates might have a weak dependence on environmental factors. It has been suggested that measurements of decay rates of silicon-32, manganese-54, and radium-226 exhibit small seasonal variations (of the order of 0.1%).[46][47][48] However, such measurements are highly susceptible to systematic errors, and a subsequent paper[49] has found no evidence for such correlations in seven other isotopes (22Na, 44Ti, 108Ag, 121Sn, 133Ba, 241Am, 238Pu), and sets upper limits on the size of any such effects. The decay of radon-222 was once reported to exhibit large 4% peak-to-peak seasonal variations (see plot),[50] which were proposed to be related to either solar flare activity or the distance from the Sun, but detailed analysis of the experiment's design flaws, along with comparisons to other, much more stringent and systematically controlled, experiments refute this claim.[51]

GSI anomaly

An unexpected series of experimental results for the rate of decay of heavy highly charged radioactive ions circulating in a storage ring has provoked theoretical activity in an effort to find a convincing explanation. The rates of weak decay of two radioactive species with half lives of about 40 s and 200 s are found to have a significant oscillatory modulation, with a period of about 7 s.[52] The observed phenomenon is known as the GSI anomaly, as the storage ring is a facility at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Darmstadt, Germany . As the decay process produces an electron neutrino, some of the proposed explanations for the observed rate oscillation invoke neutrino properties. Initial ideas related to flavour oscillation met with skepticism.[53] A more recent proposal involves mass differences between neutrino mass eigenstates.[54]

Theoretical basis

The neutrons and protons that constitute nuclei, as well as other particles that approach close enough to them, are governed by several interactions. The nuclear force (also known as residual strong force), not observed at the familiar macroscopic scale, is the most powerful force over subatomic distances. The electrostatic force is almost always significant, and, in the case of beta decay, the weak nuclear force is also involved.

The combined effects of these forces produces a number of different phenomena in which energy may be released by rearrangement of particles in the nucleus, or else the change of one type of particle into others. These rearrangements and transformations may be hindered energetically so that they do not occur immediately. In certain cases, random quantum vacuum fluctuations are theorized to promote relaxation to a lower energy state (the "decay") in a phenomenon known as quantum tunneling. Radioactive decay half-life of nuclides has been measured over timescales of 54 orders of magnitude, from 8.6(6)×10−23 seconds (for hydrogen-5) to 7.10(28)×1031 seconds (for tellurium-128).[26] The limits of these timescales are set by the sensitivity of instrumentation only, and there are no known natural limits to how brief[citation needed] or long a decay half-life for radioactive decay of a radionuclide may be.

The decay process, like all hindered energy transformations, may be analogized by a snowfield on a mountain. While friction between the ice crystals may be supporting the snow's weight, the system is inherently unstable with regard to a state of lower potential energy. A disturbance would thus facilitate the path to a state of greater entropy; the system will move towards the ground state, producing heat, and the total energy will be distributable over a larger number of quantum states thus resulting in an avalanche. The total energy does not change in this process, but, because of the second law of thermodynamics, avalanches have only been observed in one direction and that is toward the "ground state" — the state with the largest number of ways in which the available energy could be distributed.

Such a collapse (a gamma-ray decay event) requires a specific activation energy. For a snow avalanche, this energy comes as a disturbance from outside the system, although such disturbances can be arbitrarily small. In the case of an excited atomic nucleus decaying by gamma radiation in a spontaneous emission of electromagnetic radiation, the arbitrarily small disturbance is theorized to come from quantum vacuum fluctuations.[55]

A radioactive nucleus (or any excited system in quantum mechanics) is unstable, and can, thus, spontaneously stabilize to a less-excited system. The resulting transformation alters the structure of the nucleus and results in the emission of either a photon or a high-velocity particle that has mass (such as an electron, alpha particle, or other type).[56]

Hazard warning signs

-

The trefoil symbol used to warn of presence of radioactive material or ionising radiation

-

2007 ISO radioactivity hazard symbol intended for IAEA Category 1, 2 and 3 sources defined as dangerous sources capable of death or serious injury[57]

-

One of several dangerous goods transport classification signs for radioactive materials

See also

- Actinides in the environment

- Background radiation

- Chernobyl disaster

- Crimes involving radioactive substances

- Decay chain

- Decay correction

- Fallout shelter

- Geiger counter

- Induced radioactivity

- Lists of nuclear disasters and radioactive incidents

- National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements

- Nuclear engineering

- Nuclear pharmacy

- Nuclear physics

- Nuclear power

- Nuclear chain reaction

- Particle decay

- Poisson process

- Radiation therapy

- Radioactive contamination

- Radioactivity in biology

- Radiometric dating

- Transient equilibrium

Notes

- ↑ Radionuclide is the more correct term, but radioisotope is also used. The difference between isotope and nuclide is explained at Isotope § Isotope vs. nuclide.

References

Inline

- ↑ "Radioactivity: Weak Forces". EDP Sciences. https://www.radioactivity.eu.com/site/pages/Weak_Forces.htm.

- ↑ Stabin, Michael G. (2007). "3". in Stabin, Michael G. Radiation Protection and Dosimetry: An Introduction to Health Physics. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-49983-3. ISBN 978-0-387-49982-6. https://cds.cern.ch/record/1105894.

- ↑ Best, Lara; Rodrigues, George; Velker, Vikram (2013). "1.3". Radiation Oncology Primer and Review. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62070-004-4.

- ↑ Loveland, W.; Morrissey, D.; Seaborg, G.T. (2006). Modern Nuclear Chemistry. Wiley-Interscience. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-471-11532-8. Bibcode: 2005mnc..book.....L.

- ↑ Mould, Richard F. (1995). A century of X-rays and radioactivity in medicine : with emphasis on photographic records of the early years (Reprint. with minor corr ed.). Bristol: Inst. of Physics Publ.. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7503-0224-1.

- ↑ Henri Becquerel (1896). "Sur les radiations émises par phosphorescence". Comptes Rendus 122: 420–421. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k30780/f422.chemindefer.

- ↑ Comptes Rendus 122: 420 (1896), translated by Carmen Giunta. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ↑ Henri Becquerel (1896). "Sur les radiations invisibles émises par les corps phosphorescents". Comptes Rendus 122: 501–503. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k30780/f503.item.

- ↑ Comptes Rendus 122: 501–503 (1896), translated by Carmen Giunta. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ↑ Kasimir Fajans, "Radioactive transformations and the periodic system of the elements". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, Nr. 46, 1913, pp. 422–439

- ↑ Frederick Soddy, "The Radio Elements and the Periodic Law", Chem. News, Nr. 107, 1913, pp. 97–99

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 L'Annunziata, Michael F. (2007). Radioactivity: Introduction and History. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science. pp. 2. ISBN 9780080548883.

- ↑ Petrucci, Ralph H.; Harwood, William S.; Herring, F. Geoffrey (2002). General chemistry (8th ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 1025. ISBN 0-13-014329-4.

- ↑ Sansare, K.; Khanna, V.; Karjodkar, F. (2011). "Early victims of X-rays: a tribute and current perception". Dentomaxillofacial Radiology 40 (2): 123–125. doi:10.1259/dmfr/73488299. ISSN 0250-832X. PMID 21239576.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Ronald L. Kathern and Paul L. Ziemer, he First Fifty Years of Radiation Protection, physics.isu.edu". http://www.physics.isu.edu/radinf/50yrs.htm.

- ↑ Hrabak, M.; Padovan, R.S.; Kralik, M.; Ozretic, D.; Potocki, K. (July 2008). "Nikola Tesla and the Discovery of X-rays". RadioGraphics 28 (4): 1189–92. doi:10.1148/rg.284075206. PMID 18635636.

- ↑ Rentetzi, Maria (7 November 2017). "Marie Curie and the perils in radium". Physics Today. doi:10.1063/PT.6.4.20171107a. https://physicstoday.scitation.org/do/10.1063/PT.6.4.20171107a/full/. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ↑ Clarke, R.H.; J. Valentin (2009). "The History of ICRP and the Evolution of its Policies". Annals of the ICRP. ICRP Publication 109 39 (1): 75–110. doi:10.1016/j.icrp.2009.07.009. http://www.icrp.org/docs/The%20History%20of%20ICRP%20and%20the%20Evolution%20of%20its%20Policies.pdf. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ↑ Daniels, M. (2020). "Epidemiological Studies of Low-Dose Ionizing Radiation and Cancer: Summary Bias Assessment and Meta-Analysis.". J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 56 (July 1): 188–200. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgaa010. ISSN 1434-6001. PMID 32657347.

- ↑ Venturi, Sebastiano (January 2021). "Cesium in Biology, Pancreatic Cancer, and Controversy in High and Low Radiation Exposure Damage—Scientific, Environmental, Geopolitical, and Economic Aspects" (in en). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (17): 8934. doi:10.3390/ijerph18178934. PMID 34501532.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ↑ Rutherford, Ernest (6 October 1910). "Radium Standards and Nomenclature". Nature 84 (2136): 430–431. doi:10.1038/084430a0. Bibcode: 1910Natur..84..430R. https://archive.org/details/nature841910lock.

- ↑ 10 CFR 20.1005. US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. 2009. https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/cfr/part020/part020-1005.html.

- ↑ The Council of the European Communities (1979-12-21). "Council Directive 80/181/EEC of 20 December 1979 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to Unit of measurement and on the repeal of Directive 71/354/EEC". http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31980L0181:EN:NOT.

- ↑ "Radioactive Decay". http://chemed.chem.purdue.edu/genchem/topicreview/bp/ch23/modes.php#fission.

- ↑ "CH103 – CHAPTER 3: Radioactivity and Nuclear Chemistry – Chemistry" (in en-US). https://wou.edu/chemistry/courses/online-chemistry-textbooks/ch103-allied-health-chemistry/ch103-chapter-3-radioactivity/.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 26.6 26.7 26.8 Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (March 2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear physics properties \ast" (in en). Chinese Physics C 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae. ISSN 1674-1137.

- ↑ Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties". Chinese Physics C 45 (3). doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae. https://www-nds.iaea.org/amdc/ame2020/NUBASE2020.pdf.

- ↑ Clayton, Donald D. (1983). Principles of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-226-10953-4. https://archive.org/details/principlesofstel0000clay.

- ↑ "John H. Reynolds, Physics: Berkeley". The University of California, Berkeley. 2007. http://content.cdlib.org/xtf/view?docId=hb1r29n709&doc.view=content&chunk.id=div00061&toc.depth=1&brand=oac&anchor.id=0.

- ↑ "Szilard-Chalmers effect - Oxford Reference" (in en). https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100548450.

- ↑ Szilard, Leó; Chalmers, Thomas A. (1934). "Chemical separation of the radioactive element from its bombarded isotope in the Fermi effect". Nature 134 (3386): 462. doi:10.1038/134462b0. Bibcode: 1934Natur.134..462S.

- ↑ Harbottle, Garman; Sutin, Norman (1959-01-01), Emeléus, H. J.; Sharpe, A. G., eds. (in en), The Szilard-Chalmers Reaction in Solids, Advances in Inorganic Chemistry and Radiochemistry, 1, Academic Press, pp. 267–314, doi:10.1016/S0065-2792(08)60256-3, ISBN 9780120236015, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065279208602563, retrieved 2020-03-19

- ↑ Leo, William R. (1992). "Ch. 4". Statistics and the treatment of experimental data (Techniques for Nuclear and Particle Physics Experiments ed.). Springer-Verlag. https://ned.ipac.caltech.edu/level5/Leo/Stats2_2.html.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Patel, S.B. (2000). Nuclear physics: an introduction. New Delhi: New Age International. pp. 62–72. ISBN 978-81-224-0125-7.

- ↑ Introductory Nuclear Physics, K.S. Krane, 1988, John Wiley & Sons Inc, ISBN 978-0-471-80553-3

- ↑ Cetnar, Jerzy (May 2006). "General solution of Bateman equations for nuclear transmutations". Annals of Nuclear Energy 33 (7): 640–645. doi:10.1016/j.anucene.2006.02.004.

- ↑ K.S. Krane (1988). Introductory Nuclear Physics. John Wiley & Sons Inc. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-471-80553-3.

- ↑ "2018 CODATA Value: Avogadro constant". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?na. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- ↑ Emery, G T (December 1972). "Perturbation of Nuclear Decay Rates" (in en). Annual Review of Nuclear Science 22 (1): 165–202. doi:10.1146/annurev.ns.22.120172.001121. ISSN 0066-4243. Bibcode: 1972ARNPS..22..165E. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.ns.22.120172.001121. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ↑ Wang, B. (2006). "Change of the 7Be electron capture half-life in metallic environments". The European Physical Journal A 28 (3): 375–377. doi:10.1140/epja/i2006-10068-x. ISSN 1434-6001. Bibcode: 2006EPJA...28..375W.

- ↑ Jung, M. (1992). "First observation of bound-state β− decay". Physical Review Letters 69 (15): 2164–2167. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.2164. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 10046415. Bibcode: 1992PhRvL..69.2164J.

- ↑ Smoliar, M.I.; Walker, R.J.; Morgan, J.W. (1996). "Re-Os ages of group IIA, IIIA, IVA, and IVB iron meteorites". Science 271 (5252): 1099–1102. doi:10.1126/science.271.5252.1099. Bibcode: 1996Sci...271.1099S.

- ↑ Bosch, F. (1996). "Observation of bound-state beta minus decay of fully ionized 187Re: 187Re–187Os Cosmochronometry". Physical Review Letters 77 (26): 5190–5193. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.5190. PMID 10062738. Bibcode: 1996PhRvL..77.5190B.

- ↑ Bosch, F. (1996). "Observation of bound-state β– decay of fully ionized 187Re:187Re-187Os Cosmochronometry". Physical Review Letters 77 (26): 5190–5193. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.5190. PMID 10062738. Bibcode: 1996PhRvL..77.5190B.

- ↑ Emery, G.T. (1972). "Perturbation of Nuclear Decay Rates". Annual Review of Nuclear Science 22: 165–202. doi:10.1146/annurev.ns.22.120172.001121. Bibcode: 1972ARNPS..22..165E.

- ↑ "The mystery of varying nuclear decay". Physics World. 2 October 2008. http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/36108.

- ↑ Jenkins, Jere H.; Fischbach, Ephraim (2009). "Perturbation of Nuclear Decay Rates During the Solar Flare of 13 December 2006". Astroparticle Physics 31 (6): 407–411. doi:10.1016/j.astropartphys.2009.04.005. Bibcode: 2009APh....31..407J.

- ↑ Jenkins, J.H.; Fischbach, Ephraim; Buncher, John B.; Gruenwald, John T.; Krause, Dennis E.; Mattes, Joshua J. (2009). "Evidence of correlations between nuclear decay rates and Earth–Sun distance". Astroparticle Physics 32 (1): 42–46. doi:10.1016/j.astropartphys.2009.05.004. Bibcode: 2009APh....32...42J.

- ↑ Norman, E.B.; Browne, Edgardo; Shugart, Howard A.; Joshi, Tenzing H.; Firestone, Richard B. (2009). "Evidence against correlations between nuclear decay rates and Earth–Sun distance". Astroparticle Physics 31 (2): 135–137. doi:10.1016/j.astropartphys.2008.12.004. Bibcode: 2009APh....31..135N. http://donuts.berkeley.edu/papers/EarthSun.pdf. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ↑ Sturrock, P.A.; Steinitz, G.; Fischbach, E.; Javorsek, D.; Jenkins, J.H. (2012). "Analysis of gamma radiation from a radon source: Indications of a solar influence". Astroparticle Physics 36 (1): 18–25. doi:10.1016/j.astropartphys.2012.04.009. ISSN 0927-6505. Bibcode: 2012APh....36...18S.

- ↑ Pommé, S.; Lutter, G.; Marouli, M.; Kossert, K.; Nähle, O. (2018-01-01). "On the claim of modulations in radon decay and their association with solar rotation" (in en). Astroparticle Physics 97: 38–45. doi:10.1016/j.astropartphys.2017.10.011. ISSN 0927-6505. Bibcode: 2018APh....97...38P.

- ↑ "High-resolution measurement of the time-modulated orbital electron capture and of the β+ decay of hydrogen-like 142Pm60+ ions". Physics Letters B 726 (4–5): 638–645. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2013.09.033. ISSN 0370-2693. Bibcode: 2013PhLB..726..638K.

- ↑ Giunti, Carlo (2009). "The GSI Time Anomaly: Facts and Fiction". Nuclear Physics B: Proceedings Supplements 188: 43–45. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysbps.2009.02.009. ISSN 0920-5632. Bibcode: 2009NuPhS.188...43G.

- ↑ Gal, Avraham (2016). "Neutrino Signals in Electron-Capture Storage-Ring Experiments". Symmetry 8 (6): 49. doi:10.3390/sym8060049. ISSN 2073-8994. Bibcode: 2016Symm....8...49G.

- ↑ Discussion of the quantum underpinnings of spontaneous emission, as first postulated by Dirac in 1927

- ↑ Noboru Takigawa and Kouhei Washiyama (2017) Fundamentals of Nuclear Physics Springer

- ↑ IAEA news release Feb 2007

General

- "Radioactivity", Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. December 18, 2006

- Radio-activity by Ernest Rutherford Phd, Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition

External links

- The Lund/LBNL Nuclear Data Search – Contains tabulated information on radioactive decay types and energies.

- Nomenclature of nuclear chemistry

- Specific activity and related topics.

- The Live Chart of Nuclides – IAEA

- Interactive Chart of Nuclides

- Health Physics Society Public Education Website

Beach, Chandler B., ed (1914). "Becquerel Rays". The New Student's Reference Work. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

Beach, Chandler B., ed (1914). "Becquerel Rays". The New Student's Reference Work. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.- Annotated bibliography for radioactivity from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Stochastic Java applet on the decay of radioactive atoms by Wolfgang Bauer

- Stochastic Flash simulation on the decay of radioactive atoms by David M. Harrison

- "Henri Becquerel: The Discovery of Radioactivity", Becquerel's 1896 articles online and analyzed on BibNum [click 'à télécharger' for English version].

- "Radioactive change", Rutherford & Soddy article (1903), online and analyzed on Bibnum [click 'à télécharger' for English version].

|

![2007 ISO radioactivity hazard symbol intended for IAEA Category 1, 2 and 3 sources defined as dangerous sources capable of death or serious injury[57]](/wiki/images/thumb/3/35/Logo_iso_radiation.svg/120px-Logo_iso_radiation.svg.png)