Chemistry:Gossypol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

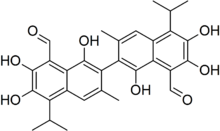

1,1′,6,6′,7,7′-Hexahydroxy-3,3′-dimethyl-5,5′-di(propan-2-yl)[2,2′-binaphthalene]-8,8′-dicarbaldehyde | |

| Identifiers | |

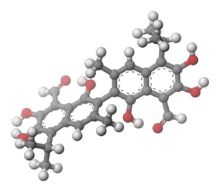

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C30H30O8 | |

| Molar mass | 518.562 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Brown solid |

| Density | 1.4 g/mL |

| Melting point | 177 to 182 °C (351 to 360 °F; 450 to 455 K) (decomposes) |

| Boiling point | 707 °C (1,305 °F; 980 K) |

| Hazards | |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Warning |

| H351 | |

| P201, P202, P281, P308+313, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Gossypol (/ˈɡɒsəpɒl/) is a natural phenol derived from the cotton plant (genus Gossypium). Gossypol is a phenolic aldehyde that permeates cells and acts as an inhibitor for several dehydrogenase enzymes. It is a yellow pigment. The structure exhibits atropisomerism, with the two enantiomers having different biochemical properties.[1]

Among other applications, it has been tested as a male oral contraceptive in China . In addition to its putative contraceptive properties, gossypol has also long been known to possess antimalarial properties.[2]

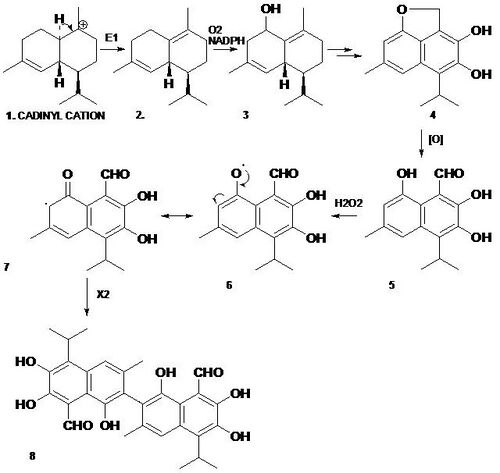

Biosynthesis

Gossypol is a terpenoid aldehyde which is formed metabolically through acetate via the isoprenoid pathway.[3] The sesquiterpene dimer undergoes a radical coupling reaction to form gossypol.[4] The biosynthesis begins when geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) are combined to make the sesquiterpene precursor farnesyl diphosphate (FPP). The cadinyl cation (1) is oxidized to 2 by (+)-δ-cadinene synthase. The (+)-δ-cadinene (2) is involved in making the basic aromatic sesquiterpene unit, homigossypol, by oxidation, which generates the 3 (8-hydroxy-δ-cadinene) with the help of (+)-δ-cadinene 8-hyroxylase. Compound 3 goes through various oxidative processes to make 4 (deoxyhemigossypol), which is oxidized by one electron into hemigossypol (5, 6, 7) and then undergoes a phenolic oxidative coupling, ortho to the phenol groups, to form gossypol (8).[5] The coupling is catalyzed by a hydrogen peroxide-dependent peroxidase enzyme, which results in the final product.[5]

Research

Contraception

A 1929 investigation in Jiangxi showed correlation between low fertility in males and use of crude cottonseed oil for cooking. The compound causing the contraceptive effect was determined to be gossypol.[6] In the 1970s, the Chinese government began researching the use of gossypol as a contraceptive. Their studies involved over 10,000 subjects, and continued for over a decade. They concluded that gossypol provided reliable contraception, could be taken orally as a tablet, and did not upset men's balance of hormones.

However, gossypol also had serious flaws. The studies also discovered an abnormally high rate (0.75%) of hypokalemia (low blood potassium levels) among subjects.[6][7] Hypokalemia causes symptoms of fatigue, muscle weakness, and at its most extreme, paralysis. In addition, about 7% of subjects reported effects on their digestive systems,[6] about 12% had increased fatigue, some subjects experienced impotence or reduced libido, and 9.9% became irreversibly infertile, apparently associated with longer treatment and greater total dose of gossypol.[6] Most subjects recovered after stopping treatment and taking potassium supplements. The same study showed taking potassium supplements during gossypol treatment did not prevent hypokalemia in primates.[7] The potassium deficiency may also be a result of the Chinese diet or genetic predisposition.[7]

In the mid-1990s, the Brazilian pharmaceutical company Hebron announced plans to market a low-dose gossypol pill called Nofertil, but the pill never came to market. Its release was indefinitely postponed due to unacceptably high rates of permanent infertility.[citation needed] 5% to 25% of the men remained azoospermic up to a year after stopping treatment.[7]

Researchers have suggested gossypol might make a good noninvasive alternative to surgical vasectomy.[8]

In 1986, in conjunction with the Chinese Ministry of Public Health and the Rockefeller Foundation, the World Health Organization formalized a decision to discontinue research into gossypol as a male contraceptive drug.[9] In addition to the other side effects, the WHO researchers were concerned about gossypol's toxicity: the -1">50 in primates is less than 10 times the contraceptive dose,[7] creating a small therapeutic window. This report effectively ended further studies of gossypol as a temporary contraceptive, but research into using it as an alternative to vasectomy continues in Austria, Brazil, Chile, China, the Dominican Republic, and Nigeria.

Toxicity

Food and animal agricultural industries must manage cotton-derivative product levels to avoid toxicity. For example, only ruminant microflora can digest gossypol, and then only to a certain level, and cottonseed oil must be refined. Genetically engineered cotton plants that contain little gossypol in the seed may still contain the compound in the stems and leaves.[10]

References

- ↑ Beise, Chase L.; Dowd, Michael K.; Reilly, Peter J. (2005). "Conformational analysis of gossypol and its derivatives by molecular mechanics". Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM 730 (1–3): 51–58. doi:10.1016/j.theochem.2005.05.010. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cbe_pubs/26.

- ↑ Dodou, Kalliopi (2005-10-28). "Investigations on gossypol: past and present developments" (in en). Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 14 (11): 1419–1434. doi:10.1517/13543784.14.11.1419. ISSN 1354-3784. PMID 16255680.

- ↑ Burgos, M.; Ito, S.; Segal, J. S.; Tran, T. P. (1997). "Effect of Gossypol on Ultrastructure of Spisula Sperm". The Biological Bulletin 193 (2): 228–229. doi:10.1086/BBLv193n2p228. PMID 28575607.

- ↑ Heinstein, P. F.; Herman, L. D.; Tove, B. S.; Smith, H. F. (1970). "Biosynthesis of Gossypol". Journal of Biological Chemistry 245 (18): 4658–4665. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)62845-5. PMID 4318479.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Dewick, P. M. (2008). Medicinal Natural Product: A Biosynthetic Approach (3rd ed.). ISBN 978-0-470-74167-2. https://www.dmt-nexus.com/doc/Medicinal%20Natural%20Products%20-%20A%20Biosynthetic%20Approach.pdf.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 YU, ZONG-HAN; CHAN, HSIAO CHANG (1998). "Gossypol as a male antifertility agent - why studies should have been continued". International Journal of Andrology 21 (1): 2–7. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2605.1998.00091.x. ISSN 0105-6263. PMID 9639145.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "Gossypol". 2011-07-27. http://malecontraceptives.org/methods/gossypol.php.

- ↑ Coutinho, F. M. (2002). "Gossypol: a contraceptive for men". Contraception 65 (4): 259–263. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(02)00294-9. PMID 12020773.

- ↑ Waites, G. M. H.; Wang, C.; Griffin, P. D. (1998). "Gossypol: Reasons for its failure to be accepted as a safe, reversible male antifertility drug". International Journal of Andrology 21 (1): 8–12. April 1998. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2605.1998.00092.x. ISSN 0105-6263. PMID 9639146.

- ↑ "Seeding Hope for Millions" (in en-US). 2018-10-16. https://today.tamu.edu/2018/10/16/edible-cottonseed-research-at-texas-am-receives-usda-approval/.

External links

|