Biology:Antibody-dependent enhancement

Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), sometimes less precisely called immune enhancement or disease enhancement, is a phenomenon in which binding of a virus to suboptimal antibodies enhances its entry into host cells, followed by its replication.[1][2] The suboptimal antibodies can result from natural infection or from vaccination. ADE may cause enhanced respiratory disease, but is not limited to respiratory disease.[3] It has been observed in HIV, RSV virus and Dengue virus and is monitored for in vaccine development.[4]

Technical description

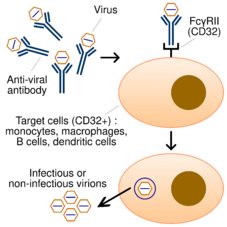

In ADE, antiviral antibodies promote viral infection of target immune cells by exploiting the phagocytic FcγR or complement pathway.[5] After interaction with a virus, the antibodies bind Fc receptors (FcR) expressed on certain immune cells or complement proteins. FcγRs bind antibodies via their fragment crystallizable region (Fc).

The process of phagocytosis is accompanied by virus degradation, but if the virus is not neutralized (either due to low affinity binding or targeting to a non-neutralizing epitope), antibody binding may result in virus escape and, therefore, more severe infection. Thus, phagocytosis can cause viral replication and the subsequent death of immune cells. Essentially, the virus “deceives” the process of phagocytosis of immune cells and uses the host's antibodies as a Trojan horse.

ADE may occur because of the non-neutralizing characteristic of an antibody, which binds viral epitopes other than those involved in host-cell attachment and entry. It may also happen when antibodies are present at sub-neutralizing concentrations (yielding occupancies on viral epitopes below the threshold for neutralization),[6][7] or when the strength of antibody-antigen interaction is below a certain threshold.[8][9] This phenomenon can lead to increased viral infectivity and virulence.

ADE can occur during the development of a primary or secondary viral infection, as well as with a virus challenge after vaccination.[1][10][11] It has been observed mainly with positive-strand RNA viruses, including flaviviruses such as dengue, yellow fever, and Zika;[12][13][14] alpha- and betacoronaviruses;[15] orthomyxoviruses such as influenza;[16] retroviruses such as HIV;[17][18][19] and orthopneumoviruses such as RSV.[20][21][22] The viruses that cause it frequently share common features such as antigenic diversity, replication ability, or ability to establish persistence in immune cells.[1]

The mechanism that involves phagocytosis of immune complexes via the FcγRII/CD32 receptor is better understood compared to the complement receptor pathway.[23][24][25] Cells that express this receptor are represented by monocytes, macrophages, and some categories of dendritic cells and B-cells. ADE is mainly mediated by IgG antibodies,[24] but IgM[26] and IgA antibodies[18][19] have also been shown to trigger it.

COVID-19

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, ADE was observed in animal studies of laboratory rodents with vaccines for SARS-CoV, the virus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). (As of January 2022), there have been no observed incidents with vaccines for COVID-19 in trials with nonhuman primates, in clinical trials with humans, or following the widespread use of approved vaccines.[27][28][29][30][31]

Influenza

Prior receipt of 2008–09 TIV (Trivalent Inactivated Influenza Vaccine) was associated with an increased risk of medically attended pH1N1 illness during the spring-summer 2009 in Canada. The occurrence of bias (selection, information) or confounding cannot be ruled out. Further experimental and epidemiological assessment is warranted. Possible biological mechanisms and immunoepidemiologic implications are considered.[32]

Natural infection and the attenuated vaccine induce antibodies that enhance the update of the homologous virus and H1N1 virus isolated several years later, demonstrating that a primary influenza A virus infection results in the induction of infection enhancing antibodies.[33]

ADE was suspected in infections with influenza A virus subtype H7N9, but knowledge is limited.

Dengue

The most widely known ADE example occurs with dengue virus.[34] Dengue is a single-stranded positive-polarity RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae. It causes disease of varying severity in humans, from dengue fever (DF), which is usually self-limited, to dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome, either of which may be life-threatening.[35] It is estimated that as many as 390 million individuals contract dengue annually.[36]

ADE may follow when a person who has previously been infected with one serotype becomes infected months or years later with a different serotype, producing higher viremia than in first-time infections. Accordingly, while primary (first) infections cause mostly minor disease (dengue fever) in children, re-infection is more likely to be associated with dengue hemorrhagic fever and/or dengue shock syndrome in both children and adults.[37]

Dengue encompasses four antigenically different serotypes (dengue virus 1–4).[38] In 2013 a fifth serotype was reported.[39] Infection induces the production of neutralizing homotypic immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies that provide lifelong immunity against the infecting serotype. Infection with dengue virus also produces some degree of cross-protective immunity against the other three serotypes.[40] Neutralizing heterotypic (cross-reactive) IgG antibodies are responsible for this cross-protective immunity, which typically persists for a period of months to a few years. These heterotypic titers decrease over long time periods (4 to 20 years).[41] While heterotypic titers decrease, homotypic IgG antibody titers increase over long time periods. This could be due to the preferential survival of long-lived memory B cells producing homotypic antibodies.[41]

In addition to neutralizing heterotypic antibodies, an infection can also induce heterotypic antibodies that neutralize the virus only partially or not at all.[42] The production of such cross-reactive, but non-neutralizing antibodies could enable severe secondary infections. By binding to but not neutralizing the virus, these antibodies cause it to behave as a "trojan horse",[43][44][45] where it is delivered into the wrong compartment of dendritic cells that have ingested the virus for destruction.[46][47] Once inside the white blood cell, the virus replicates undetected, eventually generating high virus titers and severe disease.[48]

A study conducted by Modhiran et al.[49] attempted to explain how non-neutralizing antibodies down-regulate the immune response in the host cell through the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Toll-like receptors are known to recognize extra- and intracellular viral particles and to be a major basis of the cytokines' production. In vitro experiments showed that the inflammatory cytokines and type 1 interferon production were reduced when the ADE-dengue virus complex bound to the Fc receptor of THP-1 cells. This can be explained by both a decrease of Toll-like receptor production and a modification of its signaling pathway. On the one hand, an unknown protein induced by the stimulated Fc receptor reduces Toll-like receptor transcription and translation, which reduces the capacity of the cell to detect viral proteins. On the other hand, many proteins (TRIF, TRAF6, TRAM, TIRAP, IKKα, TAB1, TAB2, NF-κB complex) involved in the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway are down-regulated, which led to a decrease in cytokine production. Two of them, TRIF and TRAF6, are respectively down-regulated by 2 proteins SARM and TANK up-regulated by the stimulated Fc receptors.

One example occurred in Cuba, lasting from 1977 to 1979. The infecting serotype was dengue virus-1. This epidemic was followed by outbreaks in 1981 and 1997. In those outbreaks; dengue virus-2 was the infecting serotype. 205 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome occurred during the 1997 outbreak, all in people older than 15 years. All but three of these cases were demonstrated to have been previously infected by dengue virus-1 during the first outbreak.[50] Furthermore, people with secondary infections with dengue virus-2 in 1997 had a 3-4 fold increased probability of developing severe disease than those with secondary infections with dengue virus-2 in 1981.[41] This scenario can be explained by the presence of sufficient neutralizing heterotypic IgG antibodies in 1981, whose titers had decreased by 1997 to the point where they no longer provided significant cross-protective immunity.

HIV-1

ADE of infection has also been reported in HIV. Like dengue virus, non-neutralizing level of antibodies have been found to enhance the viral infection through interactions of the complement system and receptors.[51] The increase in infection has been reported to be over 350 fold which is comparable to ADE in other viruses like dengue virus.[51] ADE in HIV can be complement-mediated or Fc receptor-mediated. Complements in the presence of HIV-1 positive sera have been found to enhance the infection of the MT-2 T-cell line. The Fc-receptor mediated enhancement was reported when HIV infection was enhanced by sera from HIV-1 positive guinea pig enhanced the infection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells without the presence of any complements.[52] Complement component receptors CR2, CR3 and CR4 have been found to mediate this Complement-mediated enhancement of infection.[51][53] The infection of HIV-1 leads to activation of complements. Fragments of these complements can assist viruses with infection by facilitating viral interactions with host cells that express complement receptors.[54] The deposition of complement on the virus brings the gp120 protein close to CD4 molecules on the surface of the cells, thus leading to facilitated viral entry.[54] Viruses pre-exposed to non-neutralizing complement system have also been found to enhance infections in interdigitating dendritic cells. Opsonized viruses have not only shown enhanced entry but also favorable signaling cascades for HIV replication in interdigitating dendritic cells.[55]

HIV-1 has also shown enhancement of infection in HT-29 cells when the viruses were pre-opsonized with complements C3 and C9 in seminal fluid. This enhanced rate of infection was almost 2 times greater than infection of HT-29 cells with the virus alone.[56] Subramanian et al., reported that almost 72% of serum samples out of 39 HIV-positive individuals contained complements that were known to enhance the infection. They also suggested that the presence of neutralizing antibody or antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity-mediating antibodies in the serum contains infection-enhancing antibodies.[57] The balance between the neutralizing antibodies and infection-enhancing antibodies changes as the disease progresses. During advanced stages of the disease, the proportion of infection-enhancing antibodies are generally higher than neutralizing antibodies.[58] Increase in viral protein synthesis and RNA production have been reported to occur during the complement-mediated enhancement of infection. Cells that are challenged with non-neutralizing levels of complements have been found to have accelerated release of reverse transcriptase and viral progeny.[59] The interaction of anti-HIV antibodies with non-neutralizing complement exposed viruses also aid in binding of the virus and the erythrocytes which can lead to the more efficient delivery of viruses to the immune-compromised organs.[53]

ADE in HIV has raised questions about the risk of infections to volunteers who have taken sub-neutralizing levels of vaccine just like any other viruses that exhibit ADE. Gilbert et al., in 2005 reported that there was no ADE of infection when they used the rgp120 vaccine in phase 1 and 2 trials.[60] It has been emphasized that much research needs to be done in the field of the immune response to HIV-1, information from these studies can be used to produce a more effective vaccine.

Mechanism

Interaction of a virus with antibodies must prevent the virus from attaching to the host cell entry receptors. However, instead of preventing infection of the host cell, this process can facilitate viral infection of immune cells, causing ADE.[1][5] After binding the virus, the antibody interacts with Fc or complement receptors expressed on certain immune cells. These receptors promote virus-antibody internalization by the immune cells, which should be followed by the virus destruction. However, the virus might escape the antibody complex and start its replication cycle inside the immune cell avoiding the degradation.[5][26] This happens if the virus is bound to a low-affinity antibody.

Different virus serotypes

There are several possibilities to explain the phenomenon of enhancing intracellular virus survival:

1) Antibodies against a virus of one serotype binds to a virus of a different serotype. The binding is meant to neutralize the virus from attaching to the host cell, but the virus-antibody complex also binds to the Fc-region antibody receptor (FcγR) on the immune cell. The cell internalizes the virus for programmed destruction but the virus avoids it and starts its replication cycle instead.[61]

2) Antibodies against a virus of one serotype binds to a virus of a different serotype, activating the classical pathway of the complement system. The complement cascade system binds C1Q complex attached to the virus surface protein via the antibodies, which in turn bind C1q receptor found on cells, bringing the virus and the cell close enough for a specific virus receptor to bind the virus, beginning infection.[26] This mechanism has been shown for Ebola virus in vitro[62] and some flaviviruses in vivo.[26]

Conclusion

When an antibody to a virus is unable to neutralize the virus, it forms sub-neutralizing virus-antibody complexes. Upon phagocytosis by macrophages or other immune cells, the complex may release the virus due to poor binding with the antibody. This happens during acidification and eventual fusion of the phagosome[63][64] with lysosomes.[65] The escaped virus begins its replication cycle within the cell, triggering ADE.[1][5][6]

See also

- Original antigenic sin

- Vaccine adverse event

- Other ways in which antibodies can (unusually) make an infection worse instead of better

- Blocking antibody, which can be either good or bad, depending on circumstances

- Hook effect, most relevant to in vitro tests but known to have some in vivo relevances

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Antibody-dependent enhancement of virus infection and disease". Viral Immunology 16 (1): 69–86. 2003. doi:10.1089/088282403763635465. PMID 12725690.

- ↑ "Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Viral Infections". Dynamics of Immune Activation in Viral Diseases. 19. Springer. January 2019. e31–e38. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-1045-8_2. ISBN 978-981-15-1044-1.

- ↑ "Learning from the past: development of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 19 (3): 211–219. March 2021. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00462-y. ISSN 1740-1526. PMID 33067570.

- ↑ "Why ADE Hasn't Been a Problem With COVID Vaccines" (in en). 2021-03-16. https://www.medpagetoday.com/special-reports/exclusives/91648.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "The role of IgG Fc receptors in antibody-dependent enhancement". Nature Reviews. Immunology 20 (10): 633–643. October 2020. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-00410-0. PMID 32782358.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Viral Infections". Dynamics of Immune Activation in Viral Diseases. 19. Springer. January 2019. e31–e38. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-1045-8_2. ISBN 978-981-15-1044-1.

- ↑ "Neutralization of Virus Infectivity by Antibodies: Old Problems in New Perspectives". Advances in Biology 2014: 1–24. 2014-09-09. doi:10.1155/2014/157895. PMID 27099867.

- ↑ "The potential danger of suboptimal antibody responses in COVID-19". Nature Reviews. Immunology 20 (6): 339–341. June 2020. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0321-6. PMID 32317716.

- ↑ "Medical Countermeasures Analysis of 2019-nCoV and Vaccine Risks for Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE)". SSRN Working Paper Series. 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3546070. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ↑ "Antibody-Dependent Cellular Phagocytosis in Antiviral Immune Responses". Frontiers in Immunology 10: 332. 2019. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00332. PMID 30873178.

- ↑ "Viral-Induced Enhanced Disease Illness". Frontiers in Microbiology 9: 2991. 2018-12-05. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02991. PMID 30568643.

- ↑ "Dengue viruses are enhanced by distinct populations of serotype cross-reactive antibodies in human immune sera". PLOS Pathogens 10 (10): e1004386. October 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004386. PMID 25275316.

- ↑ "Modulation of Dengue/Zika Virus Pathogenicity by Antibody-Dependent Enhancement and Strategies to Protect Against Enhancement in Zika Virus Infection". Frontiers in Immunology 9: 597. 2018. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00597. PMID 29740424.

- ↑ "Yellow fever vaccine". Vaccines (6 ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2012. pp. 870–968. ISBN 9781455700905.

- ↑ "Antibody-dependent infection of human macrophages by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus". Virology Journal 11 (1): 82. May 2014. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-11-82. PMID 24885320.

- ↑ "Antibody-dependent enhancement of influenza disease promoted by increase in hemagglutinin stem flexibility and virus fusion kinetics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116 (30): 15194–15199. July 2019. doi:10.1073/pnas.1821317116. PMID 31296560. Bibcode: 2019PNAS..11615194W.

- ↑ "Enhancing antibodies in HIV infection". Parasitology 115 (7): S127-40. 1997. doi:10.1017/s0031182097001819. PMID 9571698.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Modulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of human monocytes by IgA". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 172 (3): 855–8. September 1995. doi:10.1093/infdis/172.3.855. PMID 7658082.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "High prevalence of serum IgA HIV-1 infection-enhancing antibodies in HIV-infected persons. Masking by IgG". Journal of Immunology 154 (11): 6163–73. June 1995. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.154.11.6163. PMID 7751656.

- ↑ "In Vitro Enhancement of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection by Maternal Antibodies Does Not Explain Disease Severity in Infants". Journal of Virology 91 (21). November 2017. doi:10.1128/JVI.00851-17. PMID 28794038.

- ↑ "Antibody-dependent enhancement of respiratory syncytial virus infection by sera from young infants". Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology 1 (6): 670–7. November 1994. doi:10.1128/CDLI.1.6.670-677.1994. PMID 8556519.

- ↑ "Neutralizing and enhancing activities of human respiratory syncytial virus-specific antibodies". Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology 3 (3): 280–6. May 1996. doi:10.1128/CDLI.3.3.280-286.1996. PMID 8705669.

- ↑ "Host Range and Tissue Tropisms: Antibody-Dependent Mechanisms" (in en). Concepts in Viral Pathogenesis. New York, NY: Springer. 1984. pp. 117–122. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-5250-4_17. ISBN 978-1-4612-5250-4.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "The role of IgG Fc receptors in antibody-dependent enhancement". Nature Reviews. Immunology 20 (10): 633–643. October 2020. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-00410-0. PMID 32782358.

- ↑ "Antibody-dependent enhancement of viral infection: molecular mechanisms and in vivo implications". Reviews in Medical Virology 13 (6): 387–98. 2003. doi:10.1002/rmv.405. PMID 14625886.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 "Complement receptor mediates enhanced flavivirus replication in macrophages". The Journal of Experimental Medicine 158 (1): 258–63. July 1983. doi:10.1084/jem.158.1.258. PMID 6864163.

- ↑ Hotez, Peter J.; Bottazzi, Maria Elena (27 January 2022). "Whole Inactivated Virus and Protein-Based COVID-19 Vaccines". Annual Review of Medicine 73 (1): 55–64. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-042420-113212. ISSN 0066-4219. PMID 34637324.

- ↑ "Why ADE Hasn't Been a Problem With COVID Vaccines". www.medpagetoday.com. 16 March 2021. https://www.medpagetoday.com/special-reports/exclusives/91648.

- ↑ Haynes, Barton F.; Corey, Lawrence; Fernandes, Prabhavathi; Gilbert, Peter B.; Hotez, Peter J.; Rao, Srinivas; Santos, Michael R.; Schuitemaker, Hanneke et al. (4 November 2020). "Prospects for a safe COVID-19 vaccine". Science Translational Medicine 12 (568): eabe0948. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abe0948. ISSN 1946-6242. PMID 33077678.

- ↑ "Consensus summary report for CEPI/BC March 12-13, 2020 meeting: Assessment of risk of disease enhancement with COVID-19 vaccines". Vaccine 38 (31): 4783–4791. June 2020. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.064. PMID 32507409.

- ↑ "Prospects for a safe COVID-19 vaccine". Science Translational Medicine 12 (568): eabe0948. 2020-10-19. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abe0948. PMID 33077678.

- ↑ "Association between the 2008-09 seasonal influenza vaccine and pandemic H1N1 illness during Spring-Summer 2009: four observational studies from Canada". PLOS Medicine 7 (4): e1000258. April 2010. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000258. PMID 20386731.

- ↑ "Primary influenza A virus infection induces cross-reactive antibodies that enhance uptake of virus into Fc receptor-bearing cells". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 169 (1): 200–3. January 1994. doi:10.1093/infdis/169.1.200. PMID 8277183.

- ↑ "Model of antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue infection | Learn Science at Scitable". https://www.nature.com/scitable/content/model-of-antibody-dependent-enhancement-of-dengue-22403433/.

- ↑ "Role of dendritic cells in antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection". Journal of Virology 82 (8): 3939–51. April 2008. doi:10.1128/JVI.02484-07. PMID 18272578.

- ↑ "A rapid immunization strategy with a live-attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine elicits protective neutralizing antibody responses in non-human primates". Frontiers in Immunology 5 (2014): 263. 15 September 2014. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00263. PMID 24926294.

- ↑ "The complexity of antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection". Viruses 2 (12): 2649–62. December 2010. doi:10.3390/v2122649. PMID 21994635.

- ↑ "Dengue virus selectively induces human mast cell chemokine production". Journal of Virology 76 (16): 8408–19. August 2002. doi:10.1128/JVI.76.16.8408-8419.2002. PMID 12134044.

- ↑ "Tropical medicine. Surprising new dengue virus throws a spanner in disease control efforts". Science 342 (6157): 415. October 2013. doi:10.1126/science.342.6157.415. PMID 24159024. Bibcode: 2013Sci...342..415N.

- ↑ "Efficacy of three chloroquine-primaquine regimens for treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria in Colombia". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 75 (4): 605–9. October 2006. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2006.75.605. PMID 17038680.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 "Neutralizing antibodies after infection with dengue 1 virus". Emerging Infectious Diseases 13 (2): 282–6. February 2007. doi:10.3201/eid1302.060539. PMID 17479892.

- ↑ "Monoclonal antibody-mediated enhancement of dengue virus infection in vitro and in vivo and strategies for prevention". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (22): 9422–7. May 2007. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703498104. PMID 17517625. Bibcode: 2007PNAS..104.9422G.

- ↑ "A Trojan Horse mechanism for the spread of visna virus in monocytes". Virology 147 (1): 231–6. November 1985. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(85)90246-6. PMID 2998068.

- ↑ "Activation of terminally differentiated human monocytes/macrophages by dengue virus: productive infection, hierarchical production of innate cytokines and chemokines, and the synergistic effect of lipopolysaccharide". Journal of Virology 76 (19): 9877–87. October 2002. doi:10.1128/JVI.76.19.9877-9887.2002. PMID 12208965.

- ↑ "Fatal dengue encephalitis". The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 36 (1): 200–2. January 2005. PMID 15906668. http://www.tm.mahidol.ac.th/seameo/2005_36_1/33-3352.pdf.

- ↑ "Dengue virus life cycle: viral and host factors modulating infectivity". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 67 (16): 2773–86. August 2010. doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0357-z. PMID 20372965.

- ↑ "Dengue: a continuing global threat". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 8 (12 Suppl): S7-16. December 2010. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2460. PMID 21079655.

- ↑ "Cross-reacting antibodies enhance dengue virus infection in humans". Science 328 (5979): 745–8. May 2010. doi:10.1126/science.1185181. PMID 20448183. Bibcode: 2010Sci...328..745D.

- ↑ "Subversion of innate defenses by the interplay between DENV and pre-existing enhancing antibodies: TLRs signaling collapse". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases (PLOS ONE) 4 (12): e924. December 2010. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000924. PMID 21200427.

- ↑ "Dr. Guzman et al. Respond to Dr. Vaughn". American Journal of Epidemiology 152 (9): 804. 2000. doi:10.1093/aje/152.9.804.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 "Extensive complement-dependent enhancement of HIV-1 by autologous non-neutralising antibodies at early stages of infection". Retrovirology 8: 16. March 2011. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-8-16. PMID 21401915.

- ↑ HIV and the pathogenesis of AIDS. Wiley-Blackwell. 2007. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-55581-393-2.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "The good and evil of complement activation in HIV-1 infection". Cellular & Molecular Immunology 7 (5): 334–40. September 2010. doi:10.1038/cmi.2010.8. PMID 20228834.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 "Antibody-dependent and antibody-independent complement-mediated enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in a human, Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B-lymphocytic cell line". Journal of Virology 65 (1): 541–5. January 1991. doi:10.1128/JVI.65.1.541-545.1991. PMID 1845908.

- ↑ "Opsonization of HIV with complement enhances infection of dendritic cells and viral transfer to CD4 T cells in a CR3 and DC-SIGN-dependent manner". Journal of Immunology 178 (2): 1086–95. January 2007. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1086. PMID 17202372.

- ↑ "Opsonization of HIV-1 by semen complement enhances infection of human epithelial cells". Journal of Immunology 169 (6): 3301–6. September 2002. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3301. PMID 12218150.

- ↑ "Comparison of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific infection-enhancing and -inhibiting antibodies in AIDS patients". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 40 (6): 2141–6. June 2002. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.6.2141-2146.2002. PMID 12037078.

- ↑ "Traitors of the immune system-enhancing antibodies in HIV infection: their possible implication in HIV vaccine development". Vaccine 26 (24): 3078–85. June 2008. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.028. PMID 18241961.

- ↑ "Complement-mediated antibody-dependent enhancement of HIV-1 infection requires CD4 and complement receptors". Virology 175 (2): 600–4. April 1990. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(90)90449-2. PMID 2327077.

- ↑ "Correlation between immunologic responses to a recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine and incidence of HIV-1 infection in a phase 3 HIV-1 preventive vaccine trial". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 191 (5): 666–77. March 2005. doi:10.1086/428405. PMID 15688279.

- ↑ "Antibody-dependent enhancement of viral infection: molecular mechanisms and in vivo implications". Reviews in Medical Virology 13 (6): 387–98. 2003. doi:10.1002/rmv.405. PMID 14625886.

- ↑ "Antibody-dependent enhancement of Ebola virus infection". Journal of Virology 77 (13): 7539–44. July 2003. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.13.7539-7544.2003. PMID 12805454.

- ↑ "Phagosome maturation: going through the acid test". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 9 (10): 781–95. October 2008. doi:10.1038/nrm2515. PMID 18813294.

- ↑ "The kinetics of phagosome maturation as a function of phagosome/lysosome fusion and acquisition of hydrolytic activity". Traffic 6 (5): 413–20. May 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00284.x. PMID 15813751.

- ↑ "Dengue virus compartmentalization during antibody-enhanced infection". Scientific Reports 7 (1): 40923. January 2017. doi:10.1038/srep40923. PMID 28084461. Bibcode: 2017NatSR...740923O.

|