Biology:Papaya

| Papaya | |

|---|---|

| |

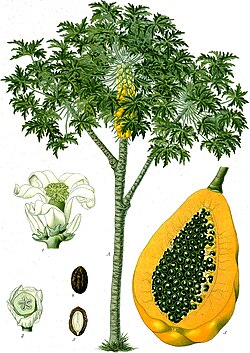

| Plant and fruit, from Koehler's Medicinal-Plants (1887) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Brassicales |

| Family: | Caricaceae |

| Genus: | Carica |

| Species: | C. papaya

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carica papaya | |

The papaya (/pəˈpaɪə/, US: /pəˈpɑːjə/), papaw, (/pəˈpɔː/[3]) or pawpaw (/ˈpɔːpɔː/[3])[4] is the plant species Carica papaya, one of the 21 accepted species in the genus Carica of the family Caricaceae.[5] It was first domesticated in Mesoamerica, within modern-day southern Mexico and Central America.[6][7] It is grown in several countries in regions with a tropical climate. In 2020, India produced 42% of the world's supply of papayas.

Etymology

The word papaya derives from Arawak via Spanish.[8] and is also the name for the plant. The name papaw or pawpaw is used alternatively for the fruit only in some regions.[6][9]

Description

The papaya is a small, sparsely branched tree, usually with a single stem growing from 5 to 10 m (16 to 33 ft) tall, with spirally arranged leaves confined to the top of the trunk. The lower trunk is conspicuously scarred where leaves and fruit were borne. The leaves are large, 50–70 cm (20–28 in) in diameter, deeply palmately lobed, with seven lobes. All plant parts contain latex in articulated laticifers.[10]

Flowers

Papayas are dioecious. The flowers are five-parted and highly dimorphic; the male flowers have the stamens fused to the petals. There are two different types of papaya flowers. The female flowers have a superior ovary and five contorted petals loosely connected at the base.[11]:235

Male and female flowers are borne in the leaf axils; the male flowers are in multiflowered dichasia, and the female ones are in few-flowered dichasia.[citation needed] The pollen grains are elongated and approximately 35 microns in length.[citation needed] The flowers are sweet-scented, open at night, and wind- or insect-pollinated.[10][12][13]

Fruit

The fruit is a large berry about 15–45 cm (6–17 3⁄4 in) long and 10–30 cm (4–11 3⁄4 in) in diameter.[10]:88 It is ripe when it feels soft (as soft as a ripe avocado or softer), its skin has attained an amber to orange hue and along the walls of the large central cavity are attached numerous black seeds.[14]

Mature tree with unripe fruit in Kinshasa

| NCBI genome ID | 513 |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | diploid |

| Genome size | 372 million bp |

| Number of chromosomes | 36 |

| Year of completion | 2014 |

Chemistry

Papaya skin, pulp, and seeds contain a variety of phytochemicals, including carotenoids and polyphenols,[15] as well as benzyl isothiocyanates and benzyl glucosinates, with skin and pulp levels that increase during ripening.[16] The carotenoids, lutein and beta-carotene, are prominent in the yellow skin, while lycopene is dominant in the red flesh (table).[17] Papaya seeds also contain the cyanogenic substance prunasin.[18] The green fruit contains papain,[6] a cysteine protease enzyme used to tenderize meat (see below).

Distribution and habitat

Native to tropical America, papaya originates from southern Mexico and Central America.[6][10][7] Papaya is also considered native to southern Florida, introduced by predecessors of the Calusa no later than AD 300.[19] Spaniards introduced papaya to the Old World in the 16th century.[6] Papaya cultivation is now nearly pantropical, spanning Hawaii, central Africa, India, and Australia.[6]

Wild populations of papaya are generally confined to naturally disturbed tropical forests.[7] Papaya is found in abundance on Everglades hammocks following major hurricanes, but is otherwise infrequent.[19] In the rain forests of southern Mexico, papaya thrives and reproduces quickly in canopy gaps while dying off in the mature closed-canopy forests.[7]

Ecology

Viruses

Papaya ringspot virus is a well-known virus within plants in Florida.[6] The first signs of the virus are yellowing and vein-clearing of younger leaves and mottling yellow leaves. Infected leaves may obtain blisters, roughen, or narrow, with blades sticking upwards from the middle of the leaves. The petioles and stems may develop dark green greasy streaks and, in time, become shorter. The ringspots are circular, C-shaped markings that are a darker green than the fruit. In the later stages of the virus, the markings may become gray and crusty. Viral infections impact growth and reduce the fruit's quality. One of the biggest effects that viral infections have on papaya is taste. As of 2010, the only way to protect papaya from this virus is genetic modification.[20]

The papaya mosaic virus destroys the plant until only a small tuft of leaves is left. The virus affects both the leaves of the plant and the fruit. Leaves show thin, irregular, dark-green lines around the borders and clear areas around the veins. The more severely affected leaves are irregular and linear in shape. The virus can infect the fruit at any stage of its maturity. Fruits as young as two weeks old have been spotted with dark-green ringspots about 1 inch (25 mm) in diameter. Rings on the fruit are most likely seen on either the stem end or the blossom end. In the early stages of the ringspots, the rings tend to be many closed circles, but as the disease develops, the rings increase in diameter consisting of one large ring. The difference between the ringspot and the mosaic viruses is the ripe fruit in the ringspot has a mottling of colors, and the mosaic does not.[21]

Fungi and oomycetes

The fungus anthracnose is known to attack papaya, especially mature fruits. The disease starts small with very few signs, such as water-soaked spots on ripening fruits. The spots become sunken, turn brown or black, and may get bigger. In some of the older spots, the fungus may produce pink spores. The fruit ends up being soft and having an off flavor because the fungus grows into the fruit.[22]

The fungus powdery mildew occurs as a superficial white presence on the leaf's surface, which is easily recognized. Tiny, light yellow spots begin on the lower surfaces of the leaf as the disease starts to make its way. The spots enlarge, and white powdery growth appears on the leaves. The infection usually appears at the upper leaf surface as white fungal growth. Powdery mildew is not as severe as other diseases.[23]

The fungus-like oomycete Phytophthora causes damping-off, root rot, stem rot, stem girdling, and fruit rot. Damping-off happens in young plants by wilting and death. The spots on established plants start as white, water-soaked lesions at the fruit and branch scars. These spots enlarge and eventually cause death. The disease's most dangerous feature is the fruit's infection, which may be toxic to consumers.[22] The roots can also be severely and rapidly infected, causing the plant to brown and wilt away, collapsing within days.

Pests

The papaya fruit fly lays its eggs inside of the fruit, possibly up to 100 or more eggs.[6] The eggs usually hatch within 12 days when they begin to feed on seeds and interior parts of the fruit. When the larvae mature, usually 16 days after being hatched, they eat their way out of the fruit, drop to the ground, and pupate in the soil to emerge within one to two weeks later as mature flies. The infected papaya turns yellow and drops to the ground after the papaya fruit fly infestation.[22]

The two-spotted spider mite is a 0.5-mm-long brown or orange-red or a green, greenish-yellow translucent oval pest. They all have needle-like piercing-sucking mouthparts and feed by piercing the plant tissue with their mouthparts, usually on the underside of the plant. The spider mites spin fine threads of webbing on the host plant, and when they remove the sap, the mesophyll tissue collapses, and a small chlorotic spot forms at the feeding sites. The leaves of the papaya fruit turn yellow, gray, or bronze. If the spider mites are not controlled, they can cause the death of the fruit.[22]

The papaya whitefly lays yellow, oval eggs that appear dusted on the undersides of the leaves. They eat papaya leaves, therefore damaging the fruit. There, the eggs developed into flies in three stages called instars. The first instar has well-developed legs and is the only mobile immature life stage. The crawlers insert their mouthparts in the lower surfaces of the leaf when they find it suitable and usually do not move again in this stage. The next instars are flattened, oval, and scale-like. In the final stage, the pupal whiteflies are more convex, with large, conspicuously red eyes.[22]

Papayas are one of the most common hosts for fruit flies like A. suspensa, which lay their eggs in overripe or spoiled papayas. The larvae of these flies then consume the fruit to gain nutrients until they can proceed into the pupal stage. This parasitism has led to extensive economic costs for nations in Central America.[24]

Cultivation

Papaya plants grow in three sexes: male, female, and hermaphrodite. The male produces only pollen, never fruit. The female produces small, inedible fruits unless pollinated. The hermaphrodite can self-pollinate since its flowers contain both male stamens and female ovaries. Almost all commercial papaya orchards contain only hermaphrodites.[13]

Originally from southern Mexico (particularly Chiapas and Veracruz), Central America, northern South America, and southern Florida[6][19] the papaya is now cultivated in most tropical countries. In cultivation, it grows rapidly, fruiting within three years. It is, however, highly frost-sensitive, limiting its production to tropical climates. Temperatures below −2 °C (29 °F) are greatly harmful, if not fatal. In Florida, California, and Texas, growth is generally limited to the southern parts of those states. It prefers sandy, well-drained soil, as standing water can kill the plant within 24 hours.[25]

Cultivars

Two kinds of papayas are commonly grown. One has sweet, red, or orange flesh, and the other has yellow flesh; in Australia , these are called "red papaya" and "yellow papaw," respectively.[26] Either kind, picked green, is called a "green papaya."[citation needed]

The large-fruited, red-fleshed 'Maradol,' 'Sunrise,' and 'Caribbean Red' papayas often sold in U.S. markets are commonly grown in Mexico and Belize.[6][27]

In 2011, Philippine researchers reported that by hybridizing papaya with Vasconcellea quercifolia, they had developed papaya resistant to papaya ringspot virus (PRV),[28] part of a long line of attempts to transfer resistance from Vasconcellea species into papaya.[29]

Genetically engineered cultivars

Carica papaya was the first transgenic fruit tree to have its genome sequenced.[30] In response to the papaya ringspot virus outbreak in Hawaii in 1998, genetically altered papaya were approved and brought to market (including 'SunUp' and 'Rainbow' varieties.) Varieties resistant to PRV have some DNA of this virus incorporated into the plant's DNA.[31][32] As of 2010, 80% of Hawaiian papaya plants were genetically modified. The modifications were made by University of Hawaii scientists, who made the modified seeds available to farmers without charge.[33][34]

In transgenic papaya, resistance is produced by inserting the viral coat protein gene into the plant's genome. Doing so seems to cause a similar protective reaction in the plant to cross-protection, which involves using an attenuated virus to protect against a more dangerous strain. Conventional varieties of transgenic papaya has reduced resistance against heterologous (not closely related to the coat gene source) strains, forcing different localities to develop their own transgenic varieties. As of 2016, one transgenic line appears able to deal with three different heterologous strains in addition to its source.[35][29]

| Papaya production – 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Country | (millions of tonnes) |

| 6.0 | |

| 1.3 | |

| 1.2 | |

| 1.1 | |

| 1.0 | |

| World | 13.9 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations [36] | |

Production

In 2020, global production of papayas was 13.9 million tonnes, led by India with 43% of the world total (table). Global papaya production grew significantly over the early 21st century, mainly as a result of increased production in India and demand by the United States.[37] The United States is the largest consumer of papaya worldwide.[12]

In South Africa papaya orchards yield up to 100 tons of fruit per hectare.[38]

Toxicity

Papaya releases a latex fluid when not ripe, possibly causing irritation and an allergic reaction in some people. Because the enzyme papain acts as an allergen in sensitive individuals,[39] meat that has been tenderized with it may induce an allergic reaction.[6]

Composition

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 179 kJ (43 kcal) |

10.82 g | |

| Sugars | 7.82 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.7 g |

0.26 g | |

0.47 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 6% 47 μg3% 274 μg89 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 2% 0.023 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.027 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 2% 0.357 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 4% 0.191 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 10% 38 μg |

| Vitamin C | 75% 62 mg |

| Vitamin E | 2% 0.3 mg |

| Vitamin K | 2% 2.6 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 2% 20 mg |

| Iron | 2% 0.25 mg |

| Magnesium | 6% 21 mg |

| Manganese | 2% 0.04 mg |

| Phosphorus | 1% 10 mg |

| Potassium | 4% 182 mg |

| Sodium | 1% 8 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.08 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 88 g |

| Lycopene | 1828 µg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Raw papaya pulp contains 88% water, 11% carbohydrates, and negligible fat and protein (table). In a 100-g amount, papaya fruit provides 43 kilocalories and is a significant source of vitamin C (75% of the Daily Value, DV) and a moderate source of folate (10% DV), but otherwise has a low content of nutrients (see table).

Uses

Culinary

The unripe green fruit is often eaten cooked due to its latex content. It is commonly eaten raw in Vietnam and Thailand. The ripe fruit of the papaya is usually eaten raw, without skin or seeds.[6] The black seeds of the papaya are edible and have a sharp, spicy taste.[6]

The raw fruit can be ripened by placing it in the sun. The young leaves, flowers, and stems can be prepared by boiling with water changes.[40]

Southeast Asia

Green papaya is used in Southeast Asian cooking, both raw and cooked. In some parts of Asia, the young leaves of the papaya are steamed and eaten like spinach.

In Myanmar, the unripe papaya are cut into slices and dipped into sour, fermented, or spicy seasonings and dips. In Myanmar and Thai recipes, the unripe papaya are cut into thinner slices to make papaya salad.[41] The reason the unripe papaya is used is because of the firmer and crunchier texture.

Papayas became a part of Filipino cuisine after being introduced to the islands via the Manila galleons.[42][43] Unripe or nearly ripe papayas (with orange flesh but still hard and green) are julienned and are commonly pickled into atchara, which is ubiquitous as a side dish to salty dishes.[44] Nearly ripe papayas can also be eaten fresh as ensaladang papaya (papaya salad) or cubed and eaten dipped in vinegar or salt. Green papaya is also a common ingredient or filling in various savory dishes such as okoy, tinola, ginataan, lumpia, and empanada, especially in the cuisines of northern Luzon.[45][46][47]

In Indonesian cuisine, the unripe green fruits and young leaves are boiled for use as part of lalab salad, while the flower buds are sautéed and stir-fried with chilies and green tomatoes as Minahasan papaya flower vegetable dish.

In Lao and Thai cuisine, unripe green papayas are used to make a type of spicy salad known in Laos as tam maak hoong and in Thailand as som tam. It is also used in Thai curries, such as kaeng som.

Green papaya is a traditional main ingredient of tinola in the Philippines .

South America

In Brazil and Paraguay, the unripe fruits are used to make sweets or preserves.[citation needed]

Papain

Both green papaya fruit and its latex are rich in papain,[6] a cysteine protease used for tenderizing meat and other proteins, as practiced currently by indigenous Americans, people of the Caribbean region, and the Philippines .[6] It is now included as a component in some powdered meat tenderizers.[6] Papaya is not suitable for gelatin-based desserts because the enzymatic properties of papain prevent gelatin from setting.[48]

Traditional medicine

In traditional medicine, papaya leaves have been believed useful as a treatment for malaria,[49] an abortifacient, a purgative, or smoked to relieve asthma.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ Contreras, A. (2016). "Carica papaya". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T20681422A20694916. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/20681422/20694916. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ↑ "Carica papaya L.". U.S. National Plant Germplasm System. 9 May 2011. https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomydetail.aspx?9147.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Papaw". Collins Dictionary. n.d.. http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/american/papaw?showCookiePolicy=true.

- ↑ In North America, papaw or pawpaw usually means the plant belonging to the Annonaceae family or its fruit. Ref.: Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (2009), published in United States.

- ↑ "Carica L.". World Flora Consortium. 2022. http://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-4000006717#children.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 Morton, Julia F. (1987). "Papaya; In: Fruits of Warm Climates". Purdue University Center for New Crops and Plant Products. pp. 336–346. http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/papaya_ars.html.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Chávez-Pesqueira, Mariana; Núñez-Farfán, Juan (1 December 2017). "Domestication and Genetics of Papaya: A Review". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 5. doi:10.3389/fevo.2017.00155.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "papaya". Online Etymology Dictionary. https://www.etymonline.com/?term=papaya. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "papaw". Online Etymology Dictionary. https://www.etymonline.com/?term=papaw. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Heywood, V.H.; Brummitt, R.K.; Culham, A.; Seberg, O. (2007). Flowering plant families of the world. Firefly Books. ISBN 9781554072064.

- ↑ Ronse De Craene, L.P. (2010). Floral diagrams: an aid to understanding flower morphology and evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49346-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=24p-LgWPA50C.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Papayas". Western Institute for Food Safety & Security, University of California at Davis. 2016. https://www.wifss.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Papayas_PDF.pdf.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Chia, C. L.; Manshardt, Richard M. (October 2001). "Why Some Papaya Plants Fail to Fruit". Fruits and Nuts (College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawaii at Manoa): 1–2. http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/F_N-5.pdf. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "papaya | Description, Cultivation, Uses, & Facts" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/plant/papaya.

- ↑ Rivera-Pastrana, D.M.; Yahia, E.M.; González-Aguilar, G.A. (2010). "Phenolic and carotenoid profiles of papaya fruit (Carica papaya L.) and their contents under low-temperature storage". J Sci Food Agric 90 (14): 2358–65. doi:10.1002/jsfa.4092. PMID 20632382. Bibcode: 2010JSFA...90.2358R.

- ↑ Rossetto, M.R.; Oliveira do Nascimento, J.R.; Purgatto, E.; Fabi, J.P.; Lajolo, F.M.; Cordenunsi, B.R. (2008). "Benzylglucosinolate, benzyl isothiocyanate, and myrosinase activity in papaya fruit during development and ripening". J Agric Food Chem 56 (20): 9592–9. doi:10.1021/jf801934x. PMID 18826320.

- ↑ Shen, Yan Hong; Yang, Fei Ying; Lu, Bing Guo; Zhao, Wan Wan; Jiang, Tao; Feng, Li; Chen, Xiao Jing; Ming, Ray (2019-01-16). "Exploring the differential mechanisms of carotenoid biosynthesis in the yellow peel and red flesh of papaya". BMC Genomics 20 (1): 49. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-5388-0. ISSN 1471-2164. PMID 30651061.

- ↑ Seigler, D.S.; Pauli, G.F.; Nahrstedt, A.; Leen, R. (2002). "Cyanogenic allosides and glucosides from Passiflora edulis and Carica papaya". Phytochemistry 60 (8): 873–82. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00170-x. PMID 12150815. Bibcode: 2002PChem..60..873S.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Ward, Daniel (2011). "Papaya". The Palmetto. https://regionalconservation.org/ircs/pdf/Ward_2011.pdf. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ↑ "Papaya ringspot virus". 2010. https://www.ars.usda.gov/research/publications/publication/?seqNo115=231839.

- ↑ Hine, B.R.; Holtsmann, O.V.; Raabe, R.D. (July 1965). "Disease of papaya in Hawaii". http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/B-136.pdf.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Mossler, M.A.; Crane, J. (2008). "Florida crop/pest management profile: papaya". University of Florida. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/PI/PI05300.pdf.

- ↑ "Powdery mildew of papaya in Hawaii". June 2012. http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/PD-90.pdf.

- ↑ Sivinski, J.M.; Calkins, C.O.; Baranowski, R.; Harris, D.; Brambila, J.; Diaz, J.; Burns, R.E.; Holler, T. et al. (April 1996). "Suppression of a Caribbean Fruit Fly (Anastrepha suspensa(Loew) Diptera: Tephritidae) Population through Augmented Releases of the ParasitoidDiachasmimorpha longicaudata(Ashmead) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae)". Biological Control 6 (2): 177–185. doi:10.1006/bcon.1996.0022. ISSN 1049-9644.

- ↑ Boning, Charles R. (2006). Florida's Best Fruiting Plants: Native and Exotic Trees, Shrubs, and Vines. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc.. pp. 166–167.

- ↑ "Papaya Varieties". Papaya Australia. 2015. http://australianpapaya.com.au/about/varieties/.

- ↑ Sagon, Candy (13 October 2004). "Maradol Papaya". Market Watch (13 Oct 2004) (The Washington Post). https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A26970-2004Oct12.html.

- ↑ Siar, S. V.; Beligan, G. A.; Sajise, A. J. C.; Villegas, V. N.; Drew, R. A. (2011). "Papaya ringspot virus resistance in Carica papaya via introgression from Vasconcellea quercifolia". Euphytica (SpringerLink) 181 (2): 159–168. doi:10.1007/s10681-011-0388-z.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Ordaz-Pérez, Daniela; Gámez-Vázquez, Josué; Hernández-Ruiz, Jesús; Espinosa-Trujillo, Edgar; Rivas-Valencia, Patricia; Castro-Montes, Ivonne (2 September 2017). "Resistencia de Vasconcellea cauliflora al Virus de la mancha anular de la papaya-potyvirus (PRSV-P) y su introgresión en Carica papaya". Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología, Mexican Journal of Phytopathology 35 (3). doi:10.18781/r.mex.fit.1703-4.

- ↑ Borrell (2008). "Papaya genome project bears fruit". Ugr.es. doi:10.1038/news.2008.772. https://www.nature.com/news/2008/080423/full/news.2008.772.html.

- ↑ "Genetically Altered Papayas Save the Harvest". mhhe.com. http://www.mhhe.com/biosci/pae/botany/botany_map/articles/article_03.html.

- ↑ "Hawaiipapaya.com". Hawaiipapaya.com. http://www.hawaiipapaya.com/rainbow.htm.

- ↑ Ronald, Pamela and McWilliams, James (14 May 2010) Genetically Engineered Distortions The New York Times, accessed 1 October 2012

- ↑ "TF5". http://www.harc-hspa.com/publications/TF5.pdf.

- ↑ Mishra, Ritesh; Gaur, Rajarshi Kumar; Patil, Basavaprabhu L. (2016). "Current Knowledge of Viruses Infecting Papaya and Their Transgenic Management". Plant Viruses: Evolution and Management. pp. 189–203. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-1406-2_11. ISBN 978-981-10-1405-5.

- ↑ "Papaya production in 2020; Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2022. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC.

- ↑ "An Overview of Global Papaya Production, Trade, and Consumption". Electronic Data Information Source, University of Florida. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fe913.

- ↑ Botha, Linda (16 March 2021). "Growing papayas: Easy to produce, tricky to market". Farmer's Weekly. https://www.farmersweekly.co.za/crops/fruit-and-nuts/growing-papayas-easy-to-produce-tricky-to-market/.

- ↑ "Papain". National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health. 27 April 2019. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/9369.

- ↑ United States Department of the Army (2009) (in en-US). The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 75. ISBN 978-1-60239-692-0. OCLC 277203364. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/277203364.

- ↑ "Burmese Papaya Salad (Myanmar Food)". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B-gsBsCAwHw.

- ↑ Alonso, Nestor (15 September 2009). "First Taste Of Mexican Cuisine". PhilStar Global. https://www.philstar.com/cebu-lifestyle/2009/09/15/505123/first-taste-mexican-cuisine.

- ↑ "Champorado and the Manila Galleon Trade". http://www.arianabautista.com/arianaeatslumpia/champorado.

- ↑ "Achara". 4 December 2014. https://www.sbs.com.au/food/recipes/achara.

- ↑ "The green papaya in Filipino cuisine". http://glossaryoffilipinofood.blogspot.com/2015/08/the-green-papaya-in-filipino-cuisine.html.

- ↑ "What to eat in Philippines?". 26 October 2017. https://foodyoushouldtry.com/eat-philippines-best-philippine-cuisine/.

- ↑ "Green Papaya Recipe". https://www.vegetarianyums.com/green-papaya-recipe.html.

- ↑ Donna Pierce (2006-01-18). "Papaya". The Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2006-01-18-0601180220-story.html.

- ↑ Titanji, V.P.; Zofou, D.; Ngemenya, M.N. (2008). "The Antimalarial Potential of Medicinal Plants Used for the Treatment of Malaria in Cameroonian Folk Medicine". African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 5 (3): 302–321. PMID 20161952.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

Wikidata ☰ Q34887 entry

|