Biology:Thaumatin

| Thaumatin family | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Thaumatin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00314 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001938 | ||||||||

| SMART | SM00205 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00286 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1thu / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 168 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1aun | ||||||||

| CDD | cd09215 | ||||||||

| Membranome | 1336 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Thaumatin I | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | Thm1 | ||||||

| PDB | 1RQW (ECOD) | ||||||

| UniProt | P02883 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Thaumatin II | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | Thm2 | ||||||

| PDB | 3wou (ECOD) | ||||||

| UniProt | P02884 | ||||||

| |||||||

Thaumatin (also known as talin) is a low-calorie sweetener and flavor modifier. The protein is often used primarily for its flavor-modifying properties and not exclusively as a sweetener.[3]

The thaumatins were first found as a mixture of proteins isolated from the katemfe fruit (Thaumatococcus daniellii) (Marantaceae) of West Africa. Although very sweet, thaumatin's taste is markedly different from sugar's. The sweetness of thaumatin builds very slowly. Perception lasts a long time, leaving a liquorice-like aftertaste at high concentrations. Thaumatin is highly water soluble, stable to heating, and stable under acidic conditions.

Biological role

Thaumatin production is induced in katemfe in response to an attack upon the plant by viroid pathogens. Several members of the thaumatin protein family display significant in vitro inhibition of hyphal growth and sporulation by various fungi. The thaumatin protein is considered a prototype for a pathogen-response protein domain. This thaumatin domain has been found in species as diverse as rice and Caenorhabditis elegans. Thaumatins are pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, which are induced by various agents ranging from ethylene to pathogens themselves, and are structurally diverse and ubiquitous in plants:[4] They include thaumatin, osmotin, tobacco major and minor PR proteins, alpha-amylase/trypsin inhibitor, and P21 and PWIR2 soybean and wheat leaf proteins. The proteins are involved in systematically-acquired stress resistance and stress responses in plants, although their precise role is unknown.[4] Thaumatin is an intensely sweet-tasting protein (on a molar basis about 100,000 times as sweet as sucrose[5]) found in the fruit of the West African plant Thaumatococcus daniellii: it is induced by attack by viroids, which are single-stranded unencapsulated RNA molecules that do not code for protein. The thaumatin protein I consists of a single polypeptide chain of 207 residues.

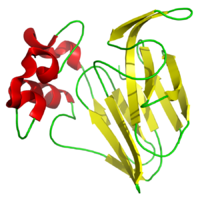

Like other PR proteins, thaumatin is predicted to have a mainly beta structure, with a high content of beta-turns and little helix.[4] Tobacco cells exposed to gradually increased salt concentrations develop a greatly increased tolerance to salt, due to the expression of osmotin,[6] a member of the PR protein family. Wheat plants attacked by barley powdery mildew express a PR protein (PWIR2), which results in resistance against that infection.[7] The similarity between this PR protein and other PR proteins and the maize alpha-amylase/trypsin inhibitor has suggested that PR proteins may act as some form of inhibitor.[7]

Within West Africa, the katemfe fruit has been locally cultivated and used to flavour foods and beverages for some time. The fruit's seeds are encased in a membranous sac, or aril, that is the source of thaumatin. In the 1970s, Tate and Lyle began extracting thaumatin from the fruit. In 1990, researchers at Unilever reported the isolation and sequencing of the two principal proteins found in thaumatin, which they dubbed thaumatin I and thaumatin II. These researchers were also able to express thaumatin in genetically engineered bacteria.

Thaumatin has been approved as a sweetener in the European Union (E957), Israel, and Japan . In the United States , it is generally recognized as safe as a flavouring agent (FEMA GRAS 3732) but not as a sweetener.

Crystallization

Since thaumatin crystallizes very quickly and easily in the presence of tartrate ions, thaumatin-tartrate mixtures are frequently used as model systems to study protein crystallization. The solubility of thaumatin, its crystal habit, and mechanism of crystal formation are dependent upon the chirality of precipitant used. When crystallized with L- tartrate, thaumatin forms bipyramidal crystals and displays a solubility that increases with temperature; with D- and meso-tartrate, it forms stubby and prismatic crystals and displays a solubility that decreases with temperature.[9] This suggests control of precipitant chirality may be an important factor in protein crystallization in general.

Characteristics

As a food ingredient, thaumatin is considered to be safe for consumption.[10][11] In a chewing gum production plant, thaumatin has been identified as an allergen. Switching from using powdered thaumatin to liquid thaumatin reduced symptoms among affected workers. Additionally, eliminating contact with powdered gum arabic (a known allergen) resulted in the disappearance of symptoms in all affected workers.[12]

Thaumatin interacts with human TAS1R3 receptor to produce a sweet taste. The interacting residues are specific to old world monkeys and apes (including humans); only these animals can perceive it as sweet.[13]

See also

- Curculin, a sweet protein from Malaysia with taste-modifying activity

- Miraculin, a protein from West Africa with taste-modifying activity

- Monellin, a sweet protein found in West Africa

- Stevia, a non-nutritive sweetener up to 150 times sweeter than sugar

- Lugduname, a sweetening agent up to 300,000 times sweeter than sugar

References

- ↑ "Automatic generation of protein structure cartoons with Pro-origami". Bioinformatics 27 (23): 3315–6. December 2011. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr575. PMID 21994221.

- ↑ DeLano Scientific LLC. (2004). Cartoon Representations.

- ↑ "Thaumatin: a natural flavor ingredient". Low-Calories Sweeteners: Present and Future. World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics. 85. 1999. pp. 129–32. doi:10.1159/000059716. ISBN 3-8055-6938-6.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Nucleotide sequence of an osmotin-like cDNA induced in tomato during viroid infection". Plant Molecular Biology 20 (6): 1199–202. December 1992. doi:10.1007/BF00028909. PMID 1463856.

- ↑ "Cloning of cDNA encoding the sweet-tasting plant protein thaumatin and its expression in Escherichia coli". Gene 18 (1): 1–12. April 1982. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(82)90050-6. PMID 7049841.

- ↑ "Molecular Cloning of Osmotin and Regulation of Its Expression by ABA and Adaptation to Low Water Potential". Plant Physiology 90 (3): 1096–101. July 1989. doi:10.1104/pp.90.3.1096. PMID 16666857.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "A wheat glutathione-S-transferase gene with transposon-like sequences in the promoter region". Plant Molecular Biology 16 (6): 1089–91. June 1991. doi:10.1007/BF00016083. PMID 1650615.

- ↑ "Microgravity protein crystallization". npj Microgravity 1: 15010. 2015. doi:10.1038/npjmgrav.2015.10. PMID 28725714.

- ↑ "Effects of Protein Purity and Precipitant Stereochemistry on the Crystallization of Thaumatin". Crystal Growth & Design 8 (12): 4200–4207. 2008. doi:10.1021/cg800616q.

- ↑ "Safety evaluation of thaumatin (Talin protein)". Food and Chemical Toxicology 21 (6): 815–23. December 1983. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(83)90218-1. PMID 6686588.

- ↑ "Thaumatin: a natural flavour ingredient". World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics 85: 129–32. 1999. doi:10.1159/000059716. ISBN 3-8055-6938-6. PMID 10647344.

- ↑ "Thaumatin and gum arabic allergy in chewing gum factory workers". American Journal of Industrial Medicine 60 (7): 664–669. July 2017. doi:10.1002/ajim.22729. PMID 28543634.

- ↑ "Five amino acid residues in cysteine-rich domain of human T1R3 were involved in the response for sweet-tasting protein, thaumatin". Biochimie 95 (7): 1502–5. July 2013. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2013.01.010. PMID 23370115.

Further reading

- "The Sweetest Thing". 31 March 2015. https://proteinswebteam.github.io/interpro-blog/2015/03/31/The-sweetest-thing/.

- Alternative sweeteners. New York: M. Dekker, Inc. 1986. ISBN 0-8247-7491-4.

- Thaumatin. Boca Raton: CRC Press. 1994. ISBN 0-8493-5196-0.

External links

|