Biology:Antibody–drug conjugate

Antibody–drug conjugates or ADCs are a class of biopharmaceutical drugs designed as a targeted therapy for treating cancer.[1] Unlike chemotherapy, ADCs are intended to target and kill tumor cells while sparing healthy cells. As of 2019, some 56 pharmaceutical companies were developing ADCs.[2]

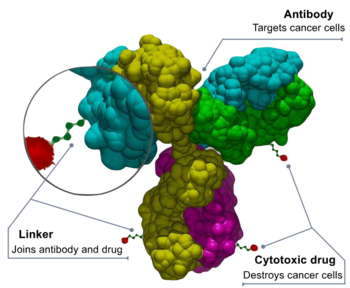

ADCs are complex molecules composed of an antibody linked to a biologically active cytotoxic (anticancer) payload or drug.[3] Antibody–drug conjugates are an example of bioconjugates and immunoconjugates.

ADCs combine the targeting properties of monoclonal antibodies with the cancer-killing capabilities of cytotoxic drugs, designed to discriminate between healthy and diseased tissue.[4][5]

Mechanism of action

An anticancer drug is coupled to an antibody that targets a specific tumor antigen (or protein) that, ideally, is only found in or on tumor cells. Antibodies attach themselves to the antigens on the surface of cancerous cells. The biochemical reaction that occurs upon attaching triggers a signal in the tumor cell, which then absorbs, or internalizes, the antibody together with the linked cytotoxin. After the ADC is internalized, the cytotoxin kills the cancer.[6] Their targeting ability was believed to limit side effects for cancer patients and give a wider therapeutic window than other chemotherapeutic agents, although this promise hasn't yet been realized in the clinic.

ADC technologies have been featured in many publications,[7][8] including scientific journals.

History

The idea of drugs that would target tumor cells and ignore others was conceived in 1900 by German Nobel laureate Paul Ehrlich; he described the drugs as a "magic bullet" due to their targeting properties.[2]

In 2001 Pfizer/Wyeth's drug Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (trade name: Mylotarg) was approved based on a study with a surrogate endpoint, through the accelerated approval process. In June 2010, after evidence accumulated showing no evidence of benefit and significant toxicity, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) forced the company to withdraw it.[9] It was reintroduced into the US market in 2017.[10]

Brentuximab vedotin (trade name: Adcetris, marketed by Seattle Genetics and Millennium/Takeda)[11] was approved for relapsed HL and relapsed systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (sALCL)) by the FDA on August 19, 2011 and received conditional marketing authorization from the European Medicines Agency in October 2012.

Trastuzumab emtansine (ado-trastuzumab emtansine or T-DM1, trade name: Kadcyla, marketed by Genentech and Roche) was approved in February 2013 for the treatment of people with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (mBC) who had received prior treatment with trastuzumab and a taxane chemotherapy.[12][13]

The European Commission approved Inotuzumab ozogamicin[14] as a monotherapy for the treatment of adults with relapsed or refractory CD22-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) on June 30, 2017 under the trade name Besponsa® (Pfizer/Wyeth),[15] followed on August 17, 2017 by the FDA.[16]

The first immunology antibody–drug conjugate (iADC), ABBV-3373,[17] showed an improvement in disease activity in a Phase 2a study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis[18] and a study with the second iADC, ABBV-154[19][20] to evaluate adverse events and change in disease activity in participants treated with subcutaneous injection of ABBV-154 is ongoing.[21]

In July 2018, Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited and Glycotope GmbH have inked a pact regarding the combination of Glycotope's investigational tumor-associated TA-MUC1 antibody gatipotuzumab and Daiichi Sankyo's proprietary ADC technology for developing gatipotuzumab antibody drug conjugate.[22]

In 2019 AstraZeneca agreed to pay up to US$6.9 billion to jointly develop DS-8201 with Japan's Daiichi Sankyo. It is intended to replace Herceptin for treating breast cancer. DS8201 carries eight payloads, compared to the usual four.[2]

Commercial products

Thirteen ADCs have received market approval by the FDA – all for oncotherapies. Belantamab mafodotin is in the process of being withdrawn from US marketing.

| Drug | Trade name | Maker | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin | Mylotarg | Pfizer/Wyeth | relapsed acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) |

| Brentuximab vedotin | Adcetris | Seattle Genetics, Millennium/Takeda | Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) |

| Trastuzumab emtansine | Kadcyla | Genentech, Roche | HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (mBC) following treatment with trastuzumab and a maytansinoid |

| Inotuzumab ozogamicin | Besponsa | Pfizer/Wyeth | relapsed or refractory CD22-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| Polatuzumab vedotin | Polivy | Genentech, Roche | relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)[23] |

| Enfortumab vedotin | Padcev | Astellas/Seattle Genetics | adult patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer who have received a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor, and a Pt-containing therapy[24] |

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan | Enhertu | AstraZeneca/Daiichi Sankyo | adult patients with unresectable or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer who have received two or more prior anti-HER2 based regimens[25] |

| Sacituzumab govitecan | Trodelvy | Immunomedics | adult patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) who have received at least two prior therapies for patients with relapsed or refractory metastatic disease[26] |

| Belantamab mafodotin | Blenrep | GlaxoSmithKline | multiple myeloma patients whose disease has progressed despite prior treatment with an immunomodulatory agent, proteasome inhibitor and anti-CD38 antibody[27] |

| Moxetumomab pasudotox | Lumoxiti | AstraZeneca | relapsed or refractory hairy cell leukemia (HCL) |

| Loncastuximab tesirine | Zynlonta | ADC Therapeutics | relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, DLBCL arising from low-grade lymphoma, and high-grade B-cell lymphoma) after two or more lines of systemic therapy |

| Tisotumab vedotin-tftv | Tivdak | Seagen Inc, Genmab | adult patients with recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer with disease progression on or after chemotherapy[28] |

| Mirvetuximab soravtansine | Elahere | ImmunoGen | treatment of adult patients with folate receptor alpha (FRα)-positive, platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer, who have received one to three prior systemic treatment regimens |

Components of an ADC

An antibody–drug conjugate consists of 3 components:[29][30] Antibody - targets the cancer cell surface and may also elicit a therapeutic response. Payload - elicits the desired therapeutic response. Linker - attaches the payload to the antibody and should be stable in circulation only releasing the payload at the desired target. Multiple approaches to conjugation have been developed for attachment to the antibody and reviewed.[31] DAR is the drug to antibody ratio and indicates the level of loading of the payload on the ADC.

Payloads

Many of the payloads for oncology ADCs (oADC) are natural product based [32] with some making covalent interactions with their target.[33] Payloads include the microtubulin inhibitors monomethyl auristatin A MMAE,[34] monomethyl auristatin F MMAF[35] and mertansine,[36] DNA binder calicheamicin[37] and topoisomerase 1 inhibitors SN-38[38] and exatecan[39] resulting in a renaissance for natural product total synthesis.[40] Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulators (GRM) represent to most active payload class for iADCs.[clarification needed] Approaches releasing marketed GRM molecules like dexamethasone[41][42] and budesonide[43] have been developed. Modified GRM molecules[44][45] have also been developed that enable the attachment of the linker with the term ADCidified describing the medicinal chemistry process of payload optimization to facilitate linker attachment.[46] Alternatives to small molecule payloads have also been investigated, for example, siRNA.[47]

Linkers

A stable link between the antibody and cytotoxic (anti-cancer) agent is a crucial aspect of an ADC.[48] A stable ADC linker ensures that less of the cytotoxic payload falls off before reaching a tumor cell, improving safety, and limiting dosages.

Linkers are based on chemical motifs including disulfides, hydrazones or peptides (cleavable), or thioethers (noncleavable). Cleavable and noncleavable linkers were proved to be safe in preclinical and clinical trials. Brentuximab vedotin includes an enzyme-sensitive cleavable linker that delivers the antimicrotubule agent monomethyl auristatin E or MMAE, a synthetic antineoplastic agent, to human-specific CD30-positive malignant cells. MMAE inhibits cell division by blocking the polymerization of tubulin. Because of its high toxicity MMAE cannot be used as a single-agent chemotherapeutic drug. However, MMAE linked to an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody (cAC10, a cell membrane protein of the tumor necrosis factor or TNF receptor) was stable in extracellular fluid. It is cleavable by cathepsin and safe for therapy. Trastuzumab emtansine is a combination of the microtubule-formation inhibitor mertansine (DM-1) and antibody trastuzumab that employs a stable, non-cleavable linker.

The availability of better and more stable linkers has changed the function of the chemical bond. The type of linker, cleavable or noncleavable, lends specific properties to the cytotoxic drug. For example, a non-cleavable linker keeps the drug within the cell. As a result, the entire antibody, linker and cytotoxic (anti-cancer) agent enter the targeted cancer cell where the antibody is degraded into an amino acid. The resulting complex – amino acid, linker and cytotoxic agent – is considered to be the active drug. In contrast, cleavable linkers are detached by enzymes in the cancer cell. The cytotoxic payload can then escape from the targeted cell and, in a process called "bystander killing", attack neighboring cells.[49]

Another type of cleavable linker, currently in development, adds an extra molecule between the cytotoxin and the cleavage site. This allows researchers to create ADCs with more flexibility without changing cleavage kinetics. Researchers are developing a new method of peptide cleavage based on Edman degradation, a method of sequencing amino acids in a peptide.[50] Also under development are site-specific conjugation (TDCs)[51] and novel conjugation techniques[52][53] to further improve stability and therapeutic index, α emitting immunoconjugates,[54] antibody-conjugated nanoparticles[55] and antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates.[56]

Anything Drug Conjugates

As the antibody–drug conjugate field has matured, a more accurate definition of ADC is now Anything-Drug Conjugate. Alternatives for the antibody targeting component now include multiple smaller antibody fragments[57] like diabodies,[58] Fab,[59] scFV,[60] and bicyclic peptides.[61]

Research

Non-natural amino acids

The first generation uses linking technologies that conjugate drugs non-selectively to cysteine or lysine residues in the antibody, resulting in a heterogeneous mixture. This approach leads to suboptimal safety and efficacy and complicates optimization of the biological, physical and pharmacological properties.[51] Site-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids generates a site for controlled and stable attachment. This enables the production of homogeneous ADCs with the antibody precisely linked to the drug and controlled ratios of antibody to drug, allowing the selection of a best-in-class ADC.[51] An Escherichia coli-based open cell-free synthesis (OCFS) allows the synthesis of proteins containing site-specifically incorporated non-natural amino acids and has been optimized for predictable high-yield protein synthesis and folding. The absence of a cell wall allows the addition of non-natural factors to the system to manipulate transcription, translation and folding to provide precise protein expression modulation.[62]

Other disease areas

The majority of ADCs under development or in clinical trials are for oncological and hematological indications.[63] This is primarily driven by the inventory of monoclonal antibodies, which target various types of cancer. However, some developers are looking to expand the application to other important disease areas.[64][65][66]

See also

- Antibody-oligonucleotide conjugate

- Immune stimulating antibody conjugate

- Small molecule drug conjugate

References

- ↑ "Antibody–drug conjugates for cancer therapy: The technological and regulatory challenges of developing drug-biologic hybrids". Biologicals 43 (5): 318–32. September 2015. doi:10.1016/j.biologicals.2015.05.006. PMID 26115630. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1045105615000500.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Matsuyama, Kanoko (2019-06-11). "Drug to replace chemotherapy may reshape cancer care". https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/drug-to-replace-chemotherapy-may-reshape-cancer-care-1.1271773.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick-Dimond, Patricia F. (March 9, 2010). "Antibody-Drug Conjugates Stage a Comeback". GEN: Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. https://www.genengnews.com/insights/antibody-drug-conjugates-stage-a-comeback/.

- ↑ "Antibody-targeted chemotherapy with CMC-544: a CD22-targeted immunoconjugate of calicheamicin for the treatment of B-lymphoid malignancies". Blood 103 (5): 1807–14. March 2004. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-07-2466. PMID 14615373.

- ↑ "Maturing antibody–drug conjugate pipeline hits 30". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 12 (5): 329–32. May 2013. doi:10.1038/nrd4009. PMID 23629491.

- ↑ "Immunoconjugates containing novel maytansinoids: promising anticancer drugs". Cancer Research 52 (1): 127–31. January 1992. PMID 1727373.

- ↑ "A One-Two Punch". The New York Times. May 31, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/01/business/a-new-class-of-cancer-drugs-may-be-less-toxic.html?pagewanted=all.

- ↑ "Ferrying a Drug Into a Cancer Cell". The New York Times. June 3, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2012/06/02/health/research/Ferrying-a-Drug-Into-a-Cancer-Cell.html?src=tp&smid=fb-share.

- ↑ "FDA: Pfizer Voluntarily Withdraws Cancer Treatment Mylotarg from U.S. Market". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/safetyinformation/safetyalertsforhumanmedicalproducts/ucm216458.htm.

- ↑ "Approved Drugs > FDA Approves Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin for CD33-positive AML". Silver Spring, USA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 1 September 2017. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm574518.htm.

- ↑ "Brentuximab vedotin (SGN35)"]. ADC Review/Journal of Antibody-drug Conjugates. http://adcreview.com/brentuximab-vedotin-sgn35/.

- ↑ "FDA Approves Genentech's Kadcyla® (Ado-Trastuzumab Emtansine), the First Antibody-Drug Conjugate for Treating Her2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer". Genentech. http://www.gene.com/media/press-releases/14347/2013-02-22/fda-approves-genentechs-kadcyla-ado-tras.

- ↑ "Ado-trastuzumab emtansine". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.. http://www.cancer.gov/drugdictionary/?CdrID=564399.

- ↑ "Inotuzumab ozogamicin (drug description)". ADC Review/Journal of Antibody-drug Conjugates. https://adcreview.com/inotuzumab-ozogamicin-cmc-544-drug-description/.

- ↑ "BESPONSA® Approved in the EU for Adult Patients with Relapsed or Refractory B-cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". 30 June 2017. http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170630005265/en/BESPONSA%C2%AE-Approved-EU-Adult-Patients-Relapsed-Refractor.

- ↑ "U.S. FDA Approves Inotuzumab Ozogamicin for Treatment of Patients with R/R B-cell precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". ADC Review/Journal of Antibody-drug Conjugates. August 17, 2017. https://adcreview.com/news/u-s-fda-approves-inotuzumab-ozogamicin-treatment-patients-rr-b-cell-precursor-acute-lymphoblastic-leukemia/.

- ↑ "Discovery of ABBV-3373, an Anti-TNF Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator Immunology Antibody Drug Conjugate". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 65 (23): 15893-15934. Dec 2022. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01579. PMID 36394224.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT03823391 for "A Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Efficacy of ABBV-3373 in Participants With Moderate to Severe Rheumatoid Arthritis" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ "Optimization of Drug-Linker to Enable Long-term Storage of Antibody-Drug Conjugate for Subcutaneous Dosing". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 66 (13): 9161-9173. Jul 2023. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00794. PMID 37379257.

- ↑ "Discovery of ABBV-154, an anti-TNF Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator Immunology Antibody-Drug Conjugate (iADC)". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 66 (17): 12544-12558. Sep 2023. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c01174. PMID 37656698.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT04888585 for "Study to Evaluate Adverse Events and Change in Disease Activity in Participants Between 18 to 75 Years of Age Treated With Subcutaneous (SC) Injections of ABBV-154 for Moderately to Severely Active Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ "Antibody Drug Conjugate Market Size, Share, Trends, Growth Analysis Report, Application Immunotherapy, Business Opportunity Industry, Future Trends Forecast - 2023 |". September 24, 2019. https://www.medgadget.com/2019/09/antibody-drug-conjugate-market-size-share-trends-growth-analysis-report-application-immunotherapy-business-opportunity-industry-future-trends-forecast-2023.html.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the (2019-06-10). "FDA approves first chemoimmunotherapy regimen for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma" (in en). https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-chemoimmunotherapy-regimen-patients-relapsed-or-refractory-diffuse-large-b-cell.

- ↑ "FDA grants accelerated approval to enfortumab vedotin-ejfv for metastatic urothelial cancer" (in en). 2019-12-18. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-enfortumab-vedotin-ejfv-metastatic-urothelial-cancer.

- ↑ "FDA approves new treatment option for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer who have progressed on available therapies" (in en). 2019-12-20. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-treatment-option-patients-her2-positive-breast-cancer-who-have-progressed-available.

- ↑ "FDA Approves New Therapy for Triple Negative Breast Cancer That Has Spread, Not Responded to Other Treatments" (in en). 2020-04-22. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-therapy-triple-negative-breast-cancer-has-spread-not-responded-other-treatments.

- ↑ "FDA granted accelerated approval to belantamab mafodotin-blmf for multiple myeloma" (in en). 2020-08-06. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-granted-accelerated-approval-belantamab-mafodotin-blmf-multiple-myeloma.

- ↑ "Seagen and Genmab Announce FDA Accelerated Approval for TIVDAK™ (tisotumab vedotin-tftv) in Previously Treated Recurrent or Metastatic Cervical Cancer". Businesswire. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210920005921/en/.

- ↑ "Advances in Antibody-Drug Conjugate Design: Current Clinical Landscape and Future Innovations". SLAS Discov 25 (8): 843–868. March 2020. doi:10.1177/2472555220912955. PMID 28303026.

- ↑ "Antibody-Drug Conjugates: A Comprehensive Review". Mol Cancer Res 18 (1): 3–19. January 2020. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-0582. PMID 31659006.

- ↑ "Recent developments in chemical conjugation strategies targeting native amino acids in proteins and their applications in antibody–drug conjugates". Chem Sci 12 (41): 13613–13647. October 2021. doi:10.1039/D1SC02973H. PMID 34760149.

- ↑ "Natural products as exquisitely potent cytotoxic payloads for antibody- drug conjugates". Curr Top Med Chem 14 (24): 2822–2834. 2015. doi:10.2174/1568026615666141208111253. PMID 30879472.

- ↑ "Chapter One - Covalent binders in drug discovery". Progress Med Chem 58 (24): 2822–2834. March 2019. doi:10.1016/bs.pmch.2018.12.002. PMID 25487009.

- ↑ "The discovery and development of brentuximab vedotin for use in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma". Nat Biotechnol 30 (7): 631–637. July 2012. doi:10.1038/nbt.2289. PMID 22781692.

- ↑ "Belantamab mafodotin for the treatment of multiple myeloma". Drugs of Today 57 (11): 653–663. November 2021. doi:10.1358/dot.2021.57.11.3319146. PMID 34821879.

- ↑ "Trastuzumab Emtansine for Residual Invasive HER2-Positive Breast Cancer". N Engl J Med 380 (7): 617–628. February 2019. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1814017. PMID 0516102.

- ↑ "Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute myeloid leukemia". Leukemia 31 (9): 1855–1868. June 2017. doi:10.1038/leu.2017.187. PMID 28607471.

- ↑ "Sacituzumab Govitecan-hziy in Refractory Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer". N Engl J Med 380 (8): 741–751. February 2019. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1814213. PMID 30786188.

- ↑ "DS-8201a, A Novel HER2-Targeting ADC with a Novel DNA Topoisomerase I Inhibitor, Demonstrates a Promising Antitumor Efficacy with Differentiation from T-DM1". Clin Cancer Res 22 (20): 5097–5108. October 2016. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2822. PMID 27026201.

- ↑ "The Role of Organic Synthesis in the Emergence and Development of Antibody-Drug Conjugates as Targeted Cancer Therapies". Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 58 (33): 11206–11241. August 2019. doi:10.1002/anie.201903498. PMID 31012193.

- ↑ "Targeting the Hemoglobin Scavenger receptor CD163 in Macrophages Highly Increases the Anti-inflammatory Potency of Dexamethasone". Mol Ther 20 (8): 1550–1558. August 2012. doi:10.1038/mt.2012.103. PMID 22643864.

- ↑ "Antibody-Directed Glucocorticoid Targeting to CD163 in M2-type Macrophages Attenuates Fructose-Induced Liver Inflammatory Changes". Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 4: 50–61. March 2017. doi:10.1016/j.omtm.2016.11.004. PMID 28344991.

- ↑ "Novel Phosphate Modified Cathepsin B Linkers: Improving Aqueous Solubility and Enhancing Payload Scope of ADCs". Bioconjug Chem 27 (9): 2081–2088. September 2016. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00337. PMID 27469406.

- ↑ "Development of Anti-CD74 Antibody-Drug Conjugates to Target Glucocorticoids to Immune Cells". Bioconjug Chem 29 (7): 2357–2369. July 2018. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00312. PMID 29923706.

- ↑ "Development of Novel Glucocorticoids for Use in Antibody-Drug Conjugates for the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases". J Med Chem 64 (16): 11958–11971. August 2021. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00541. PMID 34378927.

- ↑ "Design and Development of Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator Agonists as Immunology Antibody-Drug Conjugate (iADC) Payloads". J Med Chem 65 (6): 4500–4533. February 2022. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c02099. PMID 35133822.

- ↑ "Antibody-drug therapeutic conjugates: Potential of antibody-siRNAs in cancer therapy". J Cell Physiol 234 (10): 16724–16738. August 2019. doi:10.1002/jcp.28490. PMID 30908646.

- ↑ "Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody–drug conjugates". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 16 (5): 315–337. May 2017. doi:10.1038/nrd.2016.268. PMID 28303026.

- ↑ "Cell killing by antibody–drug conjugates". Cancer Letters 255 (2): 232–40. October 2007. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2007.04.010. PMID 17553616.

- ↑ "New method of peptide cleavage based on Edman degradation". Molecular Diversity 17 (3): 605–11. August 2013. doi:10.1007/s11030-013-9453-y. PMID 23690169.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 "Synthesis of site-specific antibody–drug conjugates using unnatural amino acids". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (40): 16101–6. October 2012. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211023109. PMID 22988081. Bibcode: 2012PNAS..10916101A.

- ↑ "Self-hydrolyzing maleimides improve the stability and pharmacological properties of antibody–drug conjugates". Nature Biotechnology 32 (10): 1059–62. October 2014. doi:10.1038/nbt.2968. PMID 25194818.

- ↑ "CBTF: new amine-to-thiol coupling reagent for preparation of antibody conjugates with increased plasma stability". Bioconjugate Chemistry 26 (2): 197–200. February 2015. doi:10.1021/bc500610g. PMID 25614935.

- ↑ "Alpha-particle emitting 213Bi-anti-EGFR immunoconjugates eradicate tumor cells independent of oxygenation". PLOS ONE 8 (5): e64730. 2013. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064730. PMID 23724085. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...864730W.

- ↑ "Antibody-conjugated nanoparticles for therapeutic applications". Current Medicinal Chemistry 19 (19): 3103–27. 2012. doi:10.2174/092986712800784667. PMID 22612698.

- ↑ "Antibody-Oligonucleotide Conjugates as Therapeutic, Imaging, and Detection Agents". Bioconjugate Chemistry 30 (10): 2483–2501. October 2019. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00306. PMID 31339691.

- ↑ "Current strategies for the discovery and bioconjugation of smaller, targetable drug conjugates tailored for solid tumor therapy". Expert Opin Drug Discov 16 (6): 613–624. June 2021. doi:10.1080/17460441.2021.1858050. PMID 33275475.

- ↑ "Improved Inhibition of Tumor Growth by Diabody-Drug Conjugates via Half-Life Extension". Bioconjug Chem 30 (4): 1232–1243. April 2019. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00170. PMID 30912649.

- ↑ "Site-Specific Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Triple Variable Domain Fab Format". Biomolecules 10 (5): 764. May 2020. doi:10.3390/biom10050764. PMID 32422893.

- ↑ "Site-Specific Conjugation of Auristatins onto Engineered scFv Using Second Generation Maleimide to Target HER2-positive Breast Cancer in Vitro". Bioconjug Chem 29 (11): 3516–3521. November 2018. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00668. PMID 30352511.

- ↑ "BT7480, a novel fully synthetic Bicycle tumor-targeted immune cell agonist™ (Bicycle TICA™) induces tumor localized CD137 agonism". J Immunother Cancer 9 (11): e002883. November 2021. doi:10.1136/jitc-2021-002883. PMID 34725211.

- ↑ "Microscale to manufacturing scale-up of cell-free cytokine production--a new approach for shortening protein production development timelines". Biotechnology and Bioengineering 108 (7): 1570–8. July 2011. doi:10.1002/bit.23103. PMID 21337337.

- ↑ "Antibody–drug conjugates for the treatment of cancer". Chemical Biology & Drug Design 81 (1): 113–21. January 2013. doi:10.1111/cbdd.12085. PMID 23253133.

- ↑ "Novel antibody-antibiotic conjugate eliminates intracellular S. aureus". Nature 527 (7578): 323–8. November 2015. doi:10.1038/nature16057. PMID 26536114. Bibcode: 2015Natur.527..323L.

- ↑ "Ambrx Collaborates with Merck to Design and Develop Biologic Drug Conjugates" (Press Release). http://www.ambrx.com/about-ambrx/06-18-2012.aspx.

- ↑ Pushing the Envelope: Advancement of ADCs Outside of Oncology In: Tumey L. (eds) Antibody-Drug Conjugates, Humana, New York, NY. Methods Mol Biol. 2078. 2020. pp. 23–36. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-9929-3_2.

|