Biology:Chacaicosaurus

| Chacaicosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

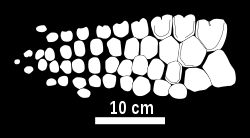

| Illustration of the partial forelimb articulated as preserved | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Ichthyosauria |

| Node: | †Neoichthyosauria |

| Genus: | †Chacaicosaurus Fernández, 1994 |

| Species: | †C. cayi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Chacaicosaurus cayi Fernández, 1994

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Chacaicosaurus is a genus of neoichthyosaurian ichthyosaur known from the Middle Jurassic of Argentina . The single known specimen of this genus was excavated from the Los Molles Formation in Neuquén Province, and is housed at the Museo Olsacher under the specimen number MOZ 5803. This specimen consists of a skull, forelimb, some vertebrae, and some additional postcranial elements. The genus was named by Marta Fernández in 1994, and contains a single species, Chacaicosaurus cayi, making it the first named distinctive ichthyosaur from the Bajocian stage. It is a medium-sized ichthyosaur with a very long snout, which bears a ridge running along each side. The forelimbs of Chacaicosaurus are small and contain four main digits.

Different authors have classified Chacaicosaurus in different ways; some consider it a thunnosaur closely related to the ophthalmosaurids, others instead place it outside of Thunnosauria, often near Hauffiopteryx. However, as it is very similar to Stenopterygius, some researchers instead classify it within that genus as S. cayi, a placement originally suggested by Fernández in 2007. The only known specimen of Chacaicosaurus appears to be an adult based on the shape of its limb bones. Chacaicosaurus inhabited open marine waters which it shared with the ophthalmosaurid ichthyosaur Mollesaurus as well as a plesiosaur, a thalattosuchian, and various invertebrates.

History of discovery

In 1990, Zulma Gasparini led an excavation team from the Museo Olsacher and the Museo de La Plata that operated in the Neuquén Basin of Argentina in Patagonia. They recovered a partial skeleton of an ichthyosaur from the Chacaico Sur locality of the Los Molles Formation, in Zapala Department, Neuquén Province. This specimen, given the number MOZ (standing for Museo Olsacher) 5803, includes a complete but damaged skull, six vertebrae, one bone from the shoulder girdle,[1] the upper end of a humerus (upper arm bone), an articulated forelimb, the upper end of a femur (thighbone), and some additional phalanges (digit bones).[2]

Marta S. Fernández named the new genus and species Chacaicosaurus cayi in 1994 to contain MOZ 5803, which serves as its holotype and is the only known specimen of the genus. The name of the genus is derived from the name of the Chacaico Sur locality and sauros, Greek for "lizard", while that of the species refers to the Mapuche sea god Cay.[2] Very few fossils of ichthyosaurs from the Aalenian to Bathonian stages of the Middle Jurassic are known, compared to the glut of Early Jurassic ichthyosaur material that has been discovered. C. cayi was the first valid ichthyosaur from this time interval to be named, with all previously named species based on remains to poor to be distinctive. Further ichthyosaurs of this time have since been found, including Mollesaurus periallus from the same time and place as Chacaicosaurus and the Aalenian German Stenopterygius aaleniensis.[3][2][1]

Description

Chacaicosaurus is a medium-sized ichthyosaur based on the size of its skull;[2] it appears to be significantly larger than Stenopterygius.[1] The long-snouted skulls of ichthyosaurs housed enlarged eyes. The limbs of ichthyosaurs were modified into rigid flippers, and the bodies of Jurassic ichthyosaurs were streamlined and spindle-shaped, with very short necks. A downward bend in the tail supported a crescentic tail fin, and a dorsal fin constructed of soft tissue was present on the back.[4][5]

Skull

The skull of the holotype measures 98 centimeters (3 ft 3 in) long, while its mandible (lower jaw bones) is 99 centimeters (3 ft 3 in) long. The skull bears a narrow snout which, characteristically, is heavily elongated, making up 80% of the skull's length, gradually sloping to a point at its front. Uniquely among ichthyosaurs, the snout bears elongate, rounded ridges that run longitudinally along the premaxillae and nasals, with one ridge on each side. The cranial proportions of Chacaicosaurus are similar to those of other long-snouted ichthyosaurs, such as Eurhinosaurus, though unlike that genus Chacaicosaurus does not have an overbite. Unusually, adult Chacaicosaurus appear to have either had very reduced teeth or been toothless.[2]

The enlarged external nares (openings for the nostrils) of Chacaicosaurus each measure about 10 centimeters (3.9 in) long, and are not positioned especially close to the orbits (eye openings). The orbits of Chacaicosaurus are very poorly preserved, so their size is unclear. In the description of the genus, Fernández estimated the sclerotic ring (the ring of bony plates supporting the eyeball) to have had a diameter of around 13 centimeters (5.1 in). She considered this to also be a reasonable rough approximation of the width of the orbit, thus concluding that Chacaicosaurus had especially small orbits.[2] While Ryosuke Motani also stated that the orbits were small in 1999,[6] Michael Maisch and Andreas Matzke in 2000 instead considered the orbits to be especially large.[7]

The wide basioccipital (rear lower braincase bone) of Chacaicosaurus lacks a peg-like projection on its front end. The surfaces on the basioccipital for articulation with two pairs of other braincase bones, the opisthotics and stapedes, are both angled towards the top of the skull, with the latter pair reclined. The occipital condyle, the knob on the back of the skull for the articulation of the spinal column, is clearly demarcated from the rest of the basioccipital. The occipital condyle is not especially large, taking up relatively little of the rear face of the basioccipital, with additional bone surface extending outwards and beneath it.[2]

Postcranial skeleton

The first cervical (neck) vertebra, the atlas, bears a triangular site for articulation with the skull, and has a prominent keel running along the middle of its underside. The cervical centra (vertebral bodies) bear deep depressions where they articulated with the neural arches, with the diapophyses (upper pairs of processes articulating with the ribs) positioned at the same height as these facets. The transverse processes (sideways projections on the vertebrae) are extensive.[2] The interclavicle (a shoulder bone positioned between the collarbones) is very wide at its center, from where the sideways and backwards projections originate.[1]

The narrow forelimbs of Chacaicosaurus are rather small compared to its skull,[2] and closely resemble those of Stenopterygius.[7] The radius (front lower arm bone) bears an incision on its front edge, as do the seven uppermost bones in the digit beneath it. The radius is comparable in size to the ulna (rear lower arm bone), in addition to the middle upper carpal (wrist bone), the intermedium. While the boundary between the lower arm bones is short, they are in contact across its entire length, with no gap between them. Distinctively, each forelimb of Chacaicosaurus contains four primary digits, the longest of which contains at least 14 elements. The foremost of these digits arises from the front upper carpal, the radiale, the second from the intermedium, and the rear two from the rear upper carpal, the ulnare. While the phalanges start out polygonal, they become increasingly small and rounded towards the tip of the flipper, where the digits are less tightly packed.[2] The phalanges are also very thick and boxy.[1] In addition to the four primary digits, there is also an accessory digit behind them, a digit which terminates before reaching the wrist.[7]

Classification

In the original 1994 description, Fernández did not find Chacaicosaurus to compare favorably to any other Jurassic ichthyosaur, therefore refraining from assigning Chacaicosaurus to a family.[2] In 1999, Fernández published the results of a phylogenetic analysis which found the closest relative of Chacaicosaurus to be Stenopterygius. These two genera were tentatively placed by Fernández in Ichthyosauridae, along with Ichthyosaurus, Ophthalmosaurus, and Mollesaurus, though she noted that this classification was still provisional as the relationships of Jurassic ichthyosaurs were poorly understood.[3] A study by Motani, published in 1999, sought to better understand ichthyosaur relationships through a phylogenetic analysis. While he did not include Chacaicosaurus in this analysis, he assigned it to the group Thunnosauria, citing similarities between its snout and forelimb and those of Stenopterygius acutirostris (a species since reassigned to Temnodontosaurus).[7][6] A year later, Maisch and Matzke also conducted a phylogenetic analysis of ichthyosaur relationships, though again did not include Chacaicosaurus in the analysis. They considered the skull of Chacaicosaurus to resemble that of Ophthalmosaurus but its forelimbs to be much more like those of Stenopterygius. Noting that Chacaicosaurus lived after Stenopterygius but before Ophthalmosaurus, the researchers considered it possible that Chacaicosaurus was an intermediate between the two genera. Due to its similarity to Stenopterygius, Maisch and Matzke placed it in the family Stenopterygiidae within Thunnosauria. They also considered it possible that rather than belonging to its own genus, C. cayi could be a derived member of Stenopterygius, but considered the evidence insufficient to combine the two genera.[7] However, in 2007, Fernández considered the differences between Chacaicosaurus and Stenopterygius to be insufficient, and synonymized them, with C. cayi becoming Stenopterygius cayi as a result.[1] In 2010, Maisch retained Chacaicosaurus as a separate genus, assigning it to Stenopterygiidae alongside Stenopterygius and Hauffiopteryx.[8]

In 2011, Valentin Fischer and colleagues conducted a cladistic analysis of thunnosaurian relationships, including Chacaicosaurus in their analysis. They found it to be the sister taxon (closest relative) of Ophthalmosauridae, with Stenopterygius as the closest relative of this grouping,[9] with another analysis in a 2012 study, also led by Fischer, finding a similar placement.[10] However, Erin Maxwell and colleagues criticized this placement in 2012, noting that the traits Fischer and colleagues had used in these studies to link Chacaicosaurus to Ophthalmosauridae were also seen in Stenopterygius, and maintained Chacaicosaurus as a synonym of that genus.[1] Nevertheless, when Fischer and colleagues constructed and ran a new analysis in 2016, they still found Chacaicosaurus to be more closely related to Ophthalmosauridae than Stenopterygius quadriscissus, though S. aaleniensis was sometimes found to be closer to the ophthalmosaurids than Chacaicosaurus.[11] Further reiterations of this analysis continued to find such a placement,[12][13] and another analysis conducted by Dirley Cortés and colleagues in 2021 also found Chacaicosaurus to be closer to ophthalmosaurs than S. quadriscissus.[14] However, not all analyses have found such a placement. A study by Benjamin Moon in 2017 did not find it to be a member of Thunnosauria, though still recovered it within Neoichthyosauria, the group that includes all post-Triassic ichthyosaurs.[15] Additionally, analyses based on the 2016 dataset of Cheng Ji and colleagues[16] also found Chacaicosaurus to be outside Thunnosauria. It was instead found to be the sister taxon of Hauffiopteryx, with the next-closest genus being Leptonectes.[17][18][19]

|

Topology from Zverkov and Jacobs, 2021.[13]

|

Topology from Bindellini and colleagues, 2021.[19]

|

Paleobiology

Ichthyosaurs were well-adapted to life in the water, though still needed to breath air. While some of the earlier ichthyosaurs would have swum by undulating like eels, Jurassic ichthyosaurs were less elongate and more streamlined, and instead would have employed carangiform or thunniform swimming, where the animal was propelled forward by side to side movement of the tail, similar to modern tuna.[4][20] As these ichthyosaurs would have been fast swimmers, they could chase down their prey instead of lying in wait for it,[21] finding it mainly by sight using their massive eyes.[22][4] Unlike modern reptiles, ichthyosaurs had high metabolisms and would have been able to regulate their body temperatures.[23] Ichthyosaurs did not lay eggs, as they could not crawl onto land; instead, they gave birth to live young underwater.[4] As ichthyosaurs grew, their bone anatomy changed. Two features of the holotype of Chacaicosaurus, the strong incisions on the leading edge of the forelimb and the rounded upper end of its humerus, indicate maturity, so Fernández considered the skeleton to have belonged to an adult.[2]

Paleoenvironment

The Los Molles Formation, the rock unit in which Chacaicosaurus was found, is a member of the Cuyo Group. While this formation, reaching up to 2,000 meters (6,600 ft) thick in some places, consists of rock laid down from the Pliensbachian stage of the Early to the Callovian stage of the Middle Jurassic,[24] Chacaicosaurus is only known from the zone containing the ammonite Emileia giebeli, dating to the early part of the Bajocian, a stage which lasted from around 170.3 to 168.3 million years ago.[2][25] The rocks in this region are mostly marl and dark shale, though there is also some sandstone. Turbidites, formed by sediment deposited by currents deep underwater, are present. These strata are thought to have been laid down in an open ocean environment, with the sea level lowering at the time.[26][24] Pollen found in the formation indicates that the climate at the time was warm, with both damp and dry conditions present on the nearby landmass.[27]

In addition to Chacaicosaurus, three other marine reptiles have been found in the Los Molles Formation: the ophthalmosaurid[10] ichthyosaur Mollesaurus, the rhomaleosaurid[28] plesiosaur Maresaurus, and a metriorhynchid[29] thalattosuchian. Like Chacaicosaurus, these three marine reptiles also lived during the early Bajocian, and all of them were well-adapted to offshore life.[26] Chacaicosaurus lived shortly after a faunal turnover in the preceding Aalenian stage, affecting both plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs. Among the ichthyosaurs, ophthalmosaurids became the dominant group while the non-ophthalmosaurid neoichthyosaurs, the group to which Chacaicosaurus belongs, went into a steep decline.[30] Invertebrates of the time include ammonites, bivalves, brachiopods, and ostracods, and the microscopic foraminifers were also present. All of these groups were abundant and diverse at the time,[26] but while the bivalves and brachiopods were at their highest species counts in the Middle Jurassic of the region, the other groups were in decline.[31]

See also

- List of ichthyosaurs

- Timeline of ichthyosaur research

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Maxwell, E. E.; Fernández, M. S.; Schoch, R. R. (2012). "First diagnostic marine reptile remains from the Aalenian (Middle Jurassic): A new ichthyosaur from southwestern Germany". PLOS ONE 7 (8): e41692. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041692. PMID 22870244.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Fernández, M. S. (1994). "A new long-snouted ichthyosaur from the Early Bajocian of Neuquén Basin, Argentina". Ameghiniana 31 (3): 291–297. https://books.google.com/books?id=Xeo9pTkWJHsC&dq=Chacaicosaurus&pg=PA291.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fernández, M. S. (1999). "A new ichthyosaur from the Los Molles Formation (Early Bajocian), Neuquen Basin, Argentina". Journal of Paleontology 73 (4): 677–681. doi:10.1017/S0022336000032492.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Sander, P. M. (2000). "Ichthyosauria: Their diversity, distribution, and phylogeny". Paläontologische Zeitschrift 74 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1007/BF02987949. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226305457.

- ↑ Eriksson, M. E.; De La Garza, R.; Horn, E.; Lindgren, J. (2022). "A review of ichthyosaur (Reptilia, Ichthyopterygia) soft tissues with implications for life reconstructions". Earth-Science Reviews 226: 103965. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.103965.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Motani, R. (1999). "Phylogeny of the Ichthyopterygia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19 (3): 473–496. doi:10.1080/02724634.1999.10011160. http://mygeologypage.ucdavis.edu/motani/pdf/Motani1999c.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Maisch, M. W.; Matzke, A. T. (2000). "The Ichthyosauria". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde. Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie) 298: 1–159. http://www.naturkundemuseum-bw.de/sites/default/files/publikationen/serie-b/B298.pdf. Retrieved 2017-10-08.

- ↑ Maisch, M. W. (2010). "Phylogeny, systematics, and origin of the Ichthyosauria – the state of the art". Palaeodiversity 3: 151–214. http://www.palaeodiversity.org/pdf/03/Palaeodiversity_Bd3_Maisch.pdf.

- ↑ Fischer, V.; Masure, E.; Arkhangelsky, M. S.; Godefroit, P. (2011). "A new Barremian (Early Cretaceous) ichthyosaur from western Russia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31 (5): 1010–1025. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.595464. https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/92828.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Fischer, V.; Maisch, M. W.; Naish, D.; Kosma, R.; Liston, J.; Joger, U.; Krüger, F. J.; Pérez, J. P. et al. (2012). "New ophthalmosaurid ichthyosaurs from the European Lower Cretaceous demonstrate extensive ichthyosaur survival across the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary". PLOS ONE 7 (1): e29234. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029234. PMID 22235274.

- ↑ Fischer, V.; Bardet, N.; Benson, R. B.; Arkhangelsky, M. S.; Friedman, M. (2016). "Extinction of fish-shaped marine reptiles associated with reduced evolutionary rates and global environmental volatility". Nature Communications 7 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1038/ncomms10825. PMID 26953824.

- ↑ Zverkov, N. G.; Efimov, V. M. (2019). "Revision of Undorosaurus, a mysterious Late Jurassic ichthyosaur of the Boreal Realm". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 17 (14): 963–993. doi:10.1080/14772019.2018.1515793. https://undor-muz.ru/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Zverkov_Efimov_2019_Undorosaurus_printed-1.pdf.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Zverkov, N. G.; Jacobs, M. L. (2021). "Revision of Nannopterygius (Ichthyosauria: Ophthalmosauridae): Reappraisal of the 'inaccessible' holotype resolves a taxonomic tangle and reveals an obscure ophthalmosaurid lineage with a wide distribution". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 191 (1): 228–275. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa028.

- ↑ Cortés, D.; Maxwell, E. E.; Larsson, H. C. E. (2021). "Re-appearance of hypercarnivore ichthyosaurs in the Cretaceous with differentiated dentition: Revision of 'Platypterygius' sachicarum (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria, Ophthalmosauridae) from Colombia". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 19 (14): 969–1002. doi:10.1080/14772019.2021.1989507.

- ↑ Moon, B. C. (2017). "A new phylogeny of ichthyosaurs (Reptilia: Diapsida)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 17 (2): 1–27. doi:10.1080/14772019.2017.1394922. https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/files/142491822/Typescript_A_new_phylogeny_of_ichthyosaurs.pdf. Retrieved 2022-07-09.

- ↑ Ji, C.; Jiang, D. Y.; Motani, R.; Rieppel, O.; Hao, W. C.; Sun, Z. Y. (2016). "Phylogeny of the Ichthyopterygia incorporating recent discoveries from South China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36 (1): e1025956. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1025956.

- ↑ Jiang, D.-Y.; Motani, R.; Huang, J.-D.; Tintori, A.; Hu, Y.-C.; Rieppel, O.; Fraser, N. C.; Ji, C. et al. (2016). "A large aberrant stem ichthyosauriform indicating early rise and demise of ichthyosauromorphs in the wake of the end-Permian extinction". Scientific Reports 6: 26232. doi:10.1038/srep26232. PMID 27211319.

- ↑ Motani, R.; Jiang, D.-Y.; Tintori, A.; Ji, C.; Huang, J.-D. (2017). "Pre- versus post-mass extinction divergence of Mesozoic marine reptiles dictated by time-scale dependence of evolutionary rates". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284 (1854): 20170241. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.0241. PMID 28515201.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Bindellini, G.; Wolniewicz, A. S.; Miedema, F.; Scheyer, T. M.; Dal Sasso, C. (2021). "Cranial anatomy of Besanosaurus leptorhynchus Dal Sasso & Pinna, 1996 (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) from the Middle Triassic Besano Formation of Monte San Giorgio, Italy/Switzerland: taxonomic and palaeobiological implications". PeerJ 9: e11179. doi:10.7717/peerj.11179. PMID 33996277.

- ↑ Gutarra, S.; Moon, B. C.; Rahman, I. A.; Palmer, C.; Lautenschlager, S.; Brimacombe, A. J.; Benton, M. J. (2019). "Effects of body plan evolution on the hydrodynamic drag and energy requirements of swimming in ichthyosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 286 (1898): 20182786. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2786. PMID 30836867.

- ↑ Massare, J. A.; Buchholtz, E. A.; Kenney, J. M.; Chomat, A.-M. (2006). "Vertebral morphology of Ophthalmosaurus natans (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) from the Jurassic Sundance Formation of Wyoming". Paludicola 5 (4): 242–254. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272787813.

- ↑ Marek, R. D.; Moon, B. C.; Williams, M.; Benton, M. J. (2015). "The skull and endocranium of a Lower Jurassic ichthyosaur based on digital reconstructions". Palaeontology 58 (4): 1–20. doi:10.1111/pala.12174. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/278032353.

- ↑ Nakajima, Y.; Houssaye, A.; Endo, H. (2014). "Osteohistology of the Early Triassic ichthyopterygian reptile Utatsusaurus hataii: Implications for early ichthyosaur biology". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 59 (2): 343–352. doi:10.4202/app.2012.0045.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Giacomone, G.; Olariu, C.; Stell, R.; Shin, M. (2020). "A coarse-grained basin floor turbidite system – the Jurassic Los Molles Formation, Neuquen Basin, Argentina". Sedimentology 67 (7): 3809–3843. doi:10.1111/sed.12771. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342104441.

- ↑ Cohen, K. M.; Finney, S. C.; Gibbard, P. L.; Fan; J.-X. (2020). "The ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart". International Commission on Stratigraphy. https://stratigraphy.org/ICSchart/ChronostratChart2020-03.pdf.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Gasparini, Z. (1997). "A new pliosaur from the Bajocian of the Neuquen Basin, Argentina". Palaeontology 40: 135–147. https://www.palass.org/sites/default/files/media/publications/palaeontology/volume_40/vol40_part1_pp135-147.pdf.

- ↑ Martínez, M. A.; Prámparo, M. B.; Quattrocchio, M. E.; Zavala, C. A.. "Depositional environments and hydrocarbon potential of the Middle Jurassic Los Molles Formation, Neuquén Basin, Argentina: Palynofacies and organic geochemical data". Revista Geológica de Chile 35 (2): 279–305. https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/bitstream/handle/11336/76918/CONICET_Digital_Nro.a91b98a0-9341-41f9-9c02-622053fe11fd_A.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

- ↑ Smith, A. S.; Dyke, G. J. (2008). "The skull of the giant predatory pliosaur Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni: Implications for plesiosaur phylogenetics". Naturwissenschaften 95 (10): 975–980. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0402-z. PMID 18523747. https://plesiosauria.com/pdf/smith&dyke_2008.pdf.

- ↑ Herrera, L. Y. (2015). "Metriorhynchidae (Crocodylomorpha: Thalattosuchia) from Upper Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous of Neuquén Basin (Argentina), with comments on the natural casts of the brain". Publicación Electrónica de la Asociación Paleontológica Argentina 15 (1): 159–171. doi:10.5710/PEAPA.09.06.2015.104. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287506372.

- ↑ Fischer, V.; Weis, R.; Thuy, B. (2021). "Refining the marine reptile turnover at the Early–Middle Jurassic transition". PeerJ 9: e10647. doi:10.7717/peerj.10647. PMID 33665003.

- ↑ Riccardi, A. C.; Damborenea, S. E.; Manceñido, M. O.; Ballent, S. C. (1994). "Middle Jurassic biostratigraphy of Argentina". Geobios 17: 423–430. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(94)80163-0.

Wikidata ☰ Q5066048 entry

|