Biology:Crucian carp

| Crucian carp | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cypriniformes |

| Family: | Cyprinidae |

| Subfamily: | Cyprininae |

| Genus: | Carassius |

| Species: | C. carassius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carassius carassius | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The crucian carp (Carassius carassius) is a medium-sized member of the common carp family Cyprinidae. It occurs widely in northern European regions. Its name derives from the Low German karusse or karutze, possibly from Medieval Latin coracinus (a kind of river fish).

Distribution

The crucian carp is a widely distributed European species, its range spanning from England to Russia; it is found as far north as the Arctic Circle in the Scandinavian countries, and as far south as central France and the region of the Black Sea.[3] Its habitat includes lakes, ponds, and slow-moving rivers. It has been established that the fish is native to England and not introduced.[4]

The crucian carp is a medium-sized cyprinid, typically 15 centimetres (5.9 in) in body length, and rarely exceeds in weight over 2 kilograms (4.4 lb),[5] but a maximum total length of 64 centimetres (25 in) has been reported for a male,[6] and the heaviest published weighed 3 kilograms (6.6 lb).[7]

They are broadly described as having a body of "golden-green shining color",[8] but a more precise source states that young fish are golden-bronze[9] but darken with maturity,[9] until they gain a dark green back, deep bronze upper flanks, and gold on the lower flanks and belly,[9] and reddish[citation needed] or orange[10] fins,[11] although other colour variations exist. One distinguishing characteristic is a convexly rounded fin, as opposed to goldfish (or C. gibelio) hybrids which have concave fins.[10][12]

The crucian carp is also the type species for the genus, which has led to confusion in the taxonomy of species native to East Asia.[citation needed]

There are reports of hybridisation between the crucian and domestic or feral goldfish,[10] which has been verified by production of viable hybrids in laboratory conditions.[10] Although the hybrids thus produced were sterile or nearly so, genetic contamination of the native population has been raised as a concern;[10] even if the hybrids cannot continue to propagate, the F1 hybrids exhibit hybrid vigour or heterosis, being much more adept at finding food and evading predators than either of their parents, which has been proposed to constitute a possible threat to the native crucian carp population.[10]

-

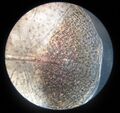

Scale

-

Brain

-

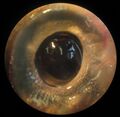

Eye

-

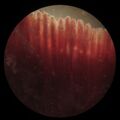

Gills

-

Eggs

Predator defenses

The variation in shape of a crucian carp can be very high. When cohabiting waters where predatory fish are present, there occurs an induced change in the morphology of the population from a sleek-bodied form to a deep-bodied form, which makes it difficult for predator fish to fit the crucian carp within its jaws.[13] However, because the deep-bodied morph is not permanent, it is expected that the trait might have some survivability trade-offs in the absence of predators.[14] Notably, the deep-bodied morph is associated with compromised immune function and resource allocation. Specifically, deep-bodied crucian carp have a lower level of baseline natural antibodies relative to the sleeker-bodied morphs.[15] In addition, crucian carp with the deep-bodied morphology exhibit reduced growth rates when compared to their sleeker-bodied counterparts.[16]

Physiology

Carassius species exhibit some remarkable physiological adaptations to their environment. For example, in entirely anoxic conditions during winter Carassius carassius can survive for considerable periods by anaerobic respiration, with ethanol as the major metabolic end product; a facility that is highly unusual among vertebrates. During summer the fish also may survive anaerobic conditions by this metabolic expedient, though only to a far more limited extent; the winter phenotype can sustain fermentation as a substitute for respiration for several weeks on end. Experimentally the fish have been maintained under anoxic conditions for 140 days. Anoxia can be tolerated longest in the coldest water, even down to 0 °C, because colder conditions lower the metabolic rate. Alcohol production occurs mainly in the muscle tissues, but also in the liver, where the process is thought to have originated. Similarly goldfish can produce alcohol in muscle tissues, but to a much more limited extent.[17]

Experimentally it has been demonstrated that the metabolic process involves the production of pyruvate from lactate, followed by decarboxylation to acetaldehyde which then is hydrogenated to ethanol as the major metabolic end product. In turn the fish largely excretes the ethanol into the water rather than accumulating it to toxic levels in the tissues. Excretion of lactate in significant quantities is not a common nor a desirable metabolic facility, but the excretion of ethanol presents no serious metabolic challenges. This metabolic expedient avoids the fatal accumulation of acid end-products of anaerobic glycolysis.[18]

Sport fishing

In Britain, leisurely or competitive catching of this fish by rod and tackle belongs in the coarse fishing category. The British rod-caught record for largest crucian is four pounds, nine ounces, (2.085 kg) landed by Martin Bowler in 2003, tied by Joshua Blavins in 2011.[19] There have been various bids for a breakage of this record since, but they were rejected as not "true" crucians" but rather, e.g. a "brown goldfish variant"[12] (i.e., hybrid born between the non-native goldfish or gibelo species and the British crucian). In the Netherlands, a typical crucian specimen of 54 cm, weighing 3 kg has been caught and photographed.[20]

Relation to goldfish

Some sources state that the goldfish (Carassius auratus) is a cultivated breed of crucian carp taken from the wild.

Aside from confusion in nomenclature, there is the practical issue of distinguishing true crucian carp from goldfish hybrids in, e.g., competitive coarse fishing. The following is based on a similar table of guidelines constructed by the Farnham Angling Society:[21]

| Crucian carp (C. carassius) | Goldfish (C. auratus) |

|---|---|

| a) snout well rounded | a) more pointed snout |

| b) Always golden bronze | b) often has a grey/greenish colour |

| c) 33 + scales along lateral line (33;[9] 31-36 scales[8]) | c) 31 or fewer scales on lateral line (27-31[9]) |

| d) Juveniles have a black spot at the base of the tail, which disappear with age. ("transient dark marking on the caudal peduncle"[10]) | d) This tail spot is never present. |

| e) The leading ray of the dorsal fin is weak | e) The leading ray of the dorsal fin is strong |

| f) The dorsal fin is higher for longer and convex in shape[8] | f) The dorsal fin is concave in shape |

| g) caudal fin bluntly lobed[9] | g) caudal fin deeply forked and sharp[9] |

Use

These carp are also occasionally kept as freshwater aquarium fish, as well as in water gardens, although they are not commonly available commercially, mainly because they are not in particularly high demand due to the presence of more colourful fish such as the koi or orfe. Crucian carp are considered a vital part of the pond ecosystem as they possess an ability to clean up the excrement of other organisms, thus preventing nitric overload.

It has been suggested that this is a heavily farmed fish worldwide; FAO's newest statistics from 2008 (pub. 2011) show total production C. crassius at 1,957,337 tonnes, worth US$2,135,857,000, ranked 9th in worldwide in aquaculture, including marine fish and crustaceans,[22] however these statistics treat the Asian C. gibelio carp as a subspecies of the European crucian carp,[23] and it is evident that the greater bulk of this number is from the Asian fish farmed in China.[23]

In terms of freshwater catches of C. crassius (read Carassius spp.), FAO's 2006 statistics show 5.53 thousand tons harvested, which ranked 13th worldwide among freshwater fishes caught. The breakdown was Kazakhstan 2.2, Japan 1.12, Serbia 0.84, Moldova 0.19, Uzbekistan 0.19, Poland 0.13.[22] In these figures, the tonnage from European countries may represent C. crassius in some part.

In Poland, crucian carp (Polish: karaś) is considered the best-tasting pan fish, and traditionally served with sour cream (karasie w śmietanie).[24] King's carp (previously Galician carp as in Galicia in the Austro-Hungarian Empire) is the breed of carp created in Poland; the "hump" is bigger than average and the scales are larger than average. Carp is included amongst the holiday foods in Poland. The tradition might have Jewish origins.[citation needed]

In Russia, this particular species is called Золотой карась meaning "golden crucian", and is one of the fish used in a borscht recipe called borshch s karasei[25] (Борщ с карасе́й) or borshch s karasyami (Борщ с карася́ми). Another classic Russian recipe is fried crucians in sour cream.[26][27][28] The variety of lake Nedzheli is highly appreciated in Yakutia and has been introduced to other lakes in the region.[29]

References

- ↑ Freyhof, J.; Kottelat, M. (2008). "Carassius carassius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T3849A10117321. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3849A10117321.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/3849/10117321. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "Synonyms of Carassius carassius Linnaeus, 1758". Fishbase. http://www.fishbase.se/Nomenclature/SynonymsList.php?ID=270&SynCode=22855&GenusName=Carassius&SpeciesName=carassius.

- ↑ Holopaien et al., 1997b

- ↑ Smartt 2007, citing Wheeler 1972, 2000, Copp etal. 2005

- ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2014). "Carassius carassius" in FishBase. February 2014 version.

- ↑ Koli, L. 1990 Suomen kalat. [Fishes of Finland]. Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö. Helsinki. 357 p. (in Finnish). Fishbase Ref. 6114

- ↑ Muus, B.J. and P. Dahlström 1968 Süßwasserfische. BLV Verlagsgesellschaft, München. 224 p. 224. Fishbase Ref.556

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Kottelat, M. and J. Freyhof 2007 Handbook of European freshwater fishes. Publications Kottelat, Cornol, Switzerland. 646 p.; Fisbhbase Ref. 59043

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Wellby, Girdler & Welcomme 2010,p.49, also color photograph is consulted

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Smartt 2007

- ↑ Wellby, Girdler & Welcomme 2010,p.49, photographed

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 FAS 2010 (website)

- ↑ Brönmark, Christer; Miner, Jeffrey G. (1992-11-20). "Predator-Induced Phenotypical Change in Body Morphology in Crucian Carp". Science 258 (5086): 1348–1350. doi:10.1126/science.258.5086.1348. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17778362. Bibcode: 1992Sci...258.1348B. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.258.5086.1348.

- ↑ "Defence versus defence: Are crucian carp trading off immune function against predator‐induced morphology?". Vinterstare, Hegemann, Nilsson, Hulthén & Brönmark, citing Dewitt, Sih, & Wilson, 1998; Tollrian & Harvell, 1999.

- ↑ Vinterstare, Jerker; Hegemann, Arne; Nilsson, Per. Anders; Hulthén, Kaj; Brönmark, Christer (2019). "Defence versus defence: Are crucian carp trading off immune function against predator‐induced morphology?". Journal of Animal Ecology. 88 (10): 1510–1521. doi:10.1111/1365-2656.13047. ISSN 0021-8790.

- ↑ Pettersson, Lars B.; Brönmark, Christer (1997). [1805:ddcoai2.0.co;2 "Density-Dependent Costs of an Inducible Morphological Defense in Crucian Carp"]. Ecology 78 (6): 1805–1815. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1997)078[1805:ddcoai2.0.co;2]. ISSN 0012-9658. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(1997)078[1805:ddcoai]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ Shoubridge, E. A. & Hochachka, P. W. (1980). Ethanol end product of vertebrate anaerobic metabolism. Science, N.Y. 209,307-308.

- ↑ Johnston, Ian A. & Bernard, Lynne M. Utilization of the Ethanol Pathway in Carp Following Exposure to Anoxia. J. exp. exp. Biol. 104, 73-78 (1983)

- ↑ British Records (rod-caught) Fish Committee 2011(website)

- ↑ "Visserslatijn® Nederland". http://www.visserslatijn.nl/specimenhunting/index.html.

- ↑ FAS 2010

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 海の幸の会 2012

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 FAO 2012

- ↑ Strybel & Strybel 2005, p.384

- ↑ Molokhovet︠s︡ 1998

- ↑ Volokh, Anne (1983). The Art of Russian Cuisine. Macmillan. p. 247. ISBN 9780026220903. https://books.google.com/books?id=UJssAAAAYAAJ&q=fried+Crucian+russian.

- ↑ Molokhovets, Elena (1992). Classic Russian Cooking: Elena Molokhovets' A Gift to Young Housewives. Indiana University Press. p. 601. ISBN 0253212103. https://books.google.com/books?id=ttlCGJxfLRUC&pg=PA601.

- ↑ Fried crucians in sour cream

- ↑ "Water of Russia - Nidzhili (in Russian)". https://water-rf.ru/%D0%92%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%BD%D1%8B%D0%B5_%D0%BE%D0%B1%D1%8A%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%82%D1%8B/1191/%D0%9D%D0%B8%D0%B4%D0%B6%D0%B8%D0%BB%D0%B8.

- Richards, Jeffrey G.; Farrell, Anthony Peter; Brauner, Colin J. (2009). Hypoxia. Academic Press. ISBN 9780080877990. https://books.google.com/books?id=cVZ92lXwNu4C&pg=PA398.

- Smartt, Joseph (2007), "A possible genetic basis for species replacement: preliminary results of interspecific hybridisation between native crucian carp Carassius carassius (L.) and introduced goldfish Carassius auratus (L.)", Aquatic Invasions 2 (1): 59–62, doi:10.3391/ai.2007.2.1.7, http://www.aquaticinvasions.net/2007/AI_2007_2_1_Smartt.pdf

- Wellby, Ian; Girdler, Ash; Welcomme, Robin (2010). Fisheries Management: A Manual for Still-Water Coarse Fisheries. John Wiley & Sons. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4051-3332-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=rREiT0TYTi8C&pg=PA49.

- (Fishing industry)

- 海の幸の会 (2012). "B 世界の漁業生産・製品流通統計". 海の幸. http://members2.jcom.home.ne.jp/uminosati/tokeigk.htm. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- FAO (2012). "Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme:Carassius carassius". http://www.fao.org/fishery/culturedspecies/Carassius_carassius/en. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- (angling)

- British Records (rod-caught) Fish Committee (2011-12-20). "British Record Coarse Fish List". Angler's Mail. https://www.advnture.com/features/world-carp-record-goes-over-100-lb.: says as of Dec 2011, Bowler, Yateley lake, Surrey 2003 and to Blavins, Verulam AC club lake, Herts, 2011, ties at 4 lb. 4 oz., 0dr. But on the same site, British Records (rod-caught) Fish Committee page, BRFC Coarse Fish Record Listings(PDF (as of 05/12/2011) ): gives a slightly different weight: Bowles 4 lb. 4 oz. 9 dr., 2.085 kg record.

- FAS (2010). "Crucian Carp". Farnham Angling Society. http://www.farnhamanglingsociety.com/species/carp-crucian.php. A catch at "5 lb 14oz .. was.. likely.. not a true Crucian as the same angler later submitted an even larger fish.. as a National Record, but it was dismissed as a Brown Goldfish variant. (The comparison chart seems to have flipped the correct usage of convex/concave)

- (culinary)

- Strybel, Robert; Strybel, Maria (2005). Polish Heritage Cookery. Hippocrene Books. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-7818-1124-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=UtA6-pyGJmMC&pg=PA384.

- Molokhovet︠s︡, Elena (1998). Classic Russian Cooking: Elena Molokhovets' a Gift to Young Housewives. Indiana University Press. p. 674. ISBN 978-0-253-21210-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=ttlCGJxfLRUC&pg=PA674.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crucian carp. |

- Fact sheet, taxonomic details, distribution maps, slideshow, and images of Carassius carassius at ZipcodeZoo.com.

- "Carassius carassius". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=163352.

- Fish Holds Breath for Months

- How carp 'hold their breath' through winter - New Scientist

Wikidata ☰ Q194031 entry

|