Biology:Directed evolution

Directed evolution (DE) is a method used in protein engineering that mimics the process of natural selection to steer proteins or nucleic acids toward a user-defined goal.[1] It consists of subjecting a gene to iterative rounds of mutagenesis (creating a library of variants), selection (expressing those variants and isolating members with the desired function) and amplification (generating a template for the next round). It can be performed in vivo (in living organisms), or in vitro (in cells or free in solution). Directed evolution is used both for protein engineering as an alternative to rationally designing modified proteins, as well as for experimental evolution studies of fundamental evolutionary principles in a controlled, laboratory environment.

History

Directed evolution has its origins in the 1960s[2] with the evolution of RNA molecules in the "Spiegelman's Monster" experiment.[3] The concept was extended to protein evolution via evolution of bacteria under selection pressures that favoured the evolution of a single gene in its genome.[4]

Early phage display techniques in the 1980s allowed targeting of mutations and selection to a single protein.[5] This enabled selection of enhanced binding proteins, but was not yet compatible with selection for catalytic activity of enzymes.[6] Methods to evolve enzymes were developed in the 1990s and brought the technique to a wider scientific audience.[7] The field rapidly expanded with new methods for making libraries of gene variants and for screening their activity.[2][8] The development of directed evolution methods was honored in 2018 with the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Frances Arnold for evolution of enzymes, and George Smith and Gregory Winter for phage display.[9]

Principles

Directed evolution is a mimic of the natural evolution cycle in a laboratory setting. Evolution requires three things to happen: variation between replicators, that the variation causes fitness differences upon which selection acts, and that this variation is heritable. In DE, a single gene is evolved by iterative rounds of mutagenesis, selection or screening, and amplification.[10] Rounds of these steps are typically repeated, using the best variant from one round as the template for the next to achieve stepwise improvements.

The likelihood of success in a directed evolution experiment is directly related to the total library size, as evaluating more mutants increases the chances of finding one with the desired properties.[11]

Generating variation

The first step in performing a cycle of directed evolution is the generation of a library of variant genes. The sequence space for random sequence is vast (10130 possible sequences for a 100 amino acid protein) and extremely sparsely populated by functional proteins. Neither experimental,[12] nor natural[13][failed verification] evolution can ever get close to sampling so many sequences. Of course, natural evolution samples variant sequences close to functional protein sequences and this is imitated in DE by mutagenising an already functional gene. Some calculations suggest it is entirely feasible that for all practical (i.e. functional and structural) purposes, protein sequence space has been fully explored during the course of evolution of life on Earth.[13]

The starting gene can be mutagenised by random point mutations (by chemical mutagens or error prone PCR)[14][15] and insertions and deletions (by transposons).[16] Gene recombination can be mimicked by DNA shuffling[17][18] of several sequences (usually of more than 70% sequence identity) to jump into regions of sequence space between the shuffled parent genes. Finally, specific regions of a gene can be systematically randomised[19] for a more focused approach based on structure and function knowledge. Depending on the method, the library generated will vary in the proportion of functional variants it contains. Even if an organism is used to express the gene of interest, by mutagenising only that gene the rest of the organism's genome remains the same and can be ignored for the evolution experiment (to the extent of providing a constant genetic environment).

Detecting fitness differences

The majority of mutations are deleterious and so libraries of mutants tend to mostly have variants with reduced activity.[20] Therefore, a high-throughput assay is vital for measuring activity to find the rare variants with beneficial mutations that improve the desired properties. Two main categories of method exist for isolating functional variants. Selection systems directly couple protein function to survival of the gene, whereas screening systems individually assay each variant and allow a quantitative threshold to be set for sorting a variant or population of variants of a desired activity. Both selection and screening can be performed in living cells (in vivo evolution) or performed directly on the protein or RNA without any cells (in vitro evolution).[21][22]

During in vivo evolution, each cell (usually bacteria or yeast) is transformed with a plasmid containing a different member of the variant library. In this way, only the gene of interest differs between the cells, with all other genes being kept the same. The cells express the protein either in their cytoplasm or surface where its function can be tested. This format has the advantage of selecting for properties in a cellular environment, which is useful when the evolved protein or RNA is to be used in living organisms. When performed without cells, DE involves using in vitro transcription translation to produce proteins or RNA free in solution or compartmentalised in artificial microdroplets. This method has the benefits of being more versatile in the selection conditions (e.g. temperature, solvent), and can express proteins that would be toxic to cells. Furthermore, in vitro evolution experiments can generate far larger libraries (up to 1015) because the library DNA need not be inserted into cells (often a limiting step).

Selection

Selection for binding activity is conceptually simple. The target molecule is immobilised on a solid support, a library of variant proteins is flowed over it, poor binders are washed away, and the remaining bound variants recovered to isolate their genes.[23] Binding of an enzyme to immobilised covalent inhibitor has been also used as an attempt to isolate active catalysts. This approach, however, only selects for single catalytic turnover and is not a good model of substrate binding or true substrate reactivity. If an enzyme activity can be made necessary for cell survival, either by synthesizing a vital metabolite, or destroying a toxin, then cell survival is a function of enzyme activity.[24][25] Such systems are generally only limited in throughput by the transformation efficiency of cells. They are also less expensive and labour-intensive than screening, however they are typically difficult to engineer, prone to artefacts and give no information on the range of activities present in the library.

Screening

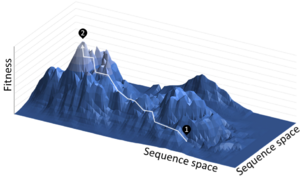

An alternative to selection is a screening system. Each variant gene is individually expressed and assayed to quantitatively measure the activity (most often by a colourgenic or fluorogenic product). The variants are then ranked and the experimenter decides which variants to use as templates for the next round of DE. Even the most high throughput assays usually have lower coverage than selection methods but give the advantage of producing detailed information on each one of the screened variants. This disaggregated data can also be used to characterise the distribution of activities in libraries which is not possible in simple selection systems. Screening systems, therefore, have advantages when it comes to experimentally characterising adaptive evolution and fitness landscapes.

Ensuring heredity

When functional proteins have been isolated, it is necessary that their genes are too, therefore a genotype–phenotype link is required.[24] This can be covalent, such as mRNA display where the mRNA gene is linked to the protein at the end of translation by puromycin.[12] Alternatively the protein and its gene can be co-localised by compartmentalisation in living cells[26] or emulsion droplets.[27] The gene sequences isolated are then amplified by PCR or by transformed host bacteria. Either the single best sequence, or a pool of sequences can be used as the template for the next round of mutagenesis. The repeated cycles of Diversification-Selection-Amplification generate protein variants adapted to the applied selection pressures.

Comparison to rational protein design

Advantages of directed evolution

Rational design of a protein relies on an in-depth knowledge of the protein structure, as well as its catalytic mechanism.[28][29] Specific changes are then made by site-directed mutagenesis in an attempt to change the function of the protein. A drawback of this is that even when the structure and mechanism of action of the protein are well known, the change due to mutation is still difficult to predict. Therefore, an advantage of DE is that there is no need to understand the mechanism of the desired activity or how mutations would affect it.[30]

Limitations of directed evolution

A restriction of directed evolution is that a high-throughput assay is required in order to measure the effects of a large number of different random mutations. This can require extensive research and development before it can be used for directed evolution. Additionally, such assays are often highly specific to monitoring a particular activity and so are not transferable to new DE experiments.[31]

Additionally, selecting for improvement in the assayed function simply generates improvements in the assayed function. To understand how these improvements are achieved, the properties of the evolving enzyme have to be measured. Improvement of the assayed activity can be due to improvements in enzyme catalytic activity or enzyme concentration. There is also no guarantee that improvement on one substrate will improve activity on another. This is particularly important when the desired activity cannot be directly screened or selected for and so a ‘proxy’ substrate is used. DE can lead to evolutionary specialisation to the proxy without improving the desired activity. Consequently, choosing appropriate screening or selection conditions is vital for successful DE.[32]

The speed of evolution in an experiment also poses a limitation on the utility of directed evolution. For instance, evolution of a particular phenotype, while theoretically feasible, may occur on time-scales that are not practically feasible.[33] Recent theoretical approaches have aimed to overcome the limitation of speed through an application of counter-diabatic driving techniques from statistical physics, though this has yet to be implemented in a directed evolution experiment.[34]

Combinatorial approaches

Combined, 'semi-rational' approaches are being investigated to address the limitations of both rational design and directed evolution.[1][35] Beneficial mutations are rare, so large numbers of random mutants have to be screened to find improved variants. 'Focused libraries' concentrate on randomising regions thought to be richer in beneficial mutations for the mutagenesis step of DE. A focused library contains fewer variants than a traditional random mutagenesis library and so does not require such high-throughput screening.

Creating a focused library requires some knowledge of which residues in the structure to mutate. For example, knowledge of the active site of an enzyme may allow just the residues known to interact with the substrate to be randomised.[36][37] Alternatively, knowledge of which protein regions are variable in nature can guide mutagenesis in just those regions.[38][39]

Applications

Directed evolution is frequently used for protein engineering as an alternative to rational design,[40] but can also be used to investigate fundamental questions of enzyme evolution.[41]

Protein engineering

As a protein engineering tool, DE has been most successful in three areas:

- Improving protein stability for biotechnological use at high temperatures or in harsh solvents[42][43][44]

- Improving binding affinity of therapeutic antibodies (Affinity maturation)[45] and the activity of de novo designed enzymes[30]

- Altering substrate specificity of existing enzymes,[46][47][48][49] (often for use in industry)[40]

Evolution studies

The study of natural evolution is traditionally based on extant organisms and their genes. However, research is fundamentally limited by the lack of fossils (and particularly the lack of ancient DNA sequences)[50][51] and incomplete knowledge of ancient environmental conditions. Directed evolution investigates evolution in a controlled system of genes for individual enzymes,[52][53][35] ribozymes[54] and replicators[55][3] (similar to experimental evolution of eukaryotes,[56][57] prokaryotes[58] and viruses[59]).

DE allows control of selection pressure, mutation rate and environment (both the abiotic environment such as temperature, and the biotic environment, such as other genes in the organism). Additionally, there is a complete record of all evolutionary intermediate genes. This allows for detailed measurements of evolutionary processes, for example epistasis, evolvability, adaptive constraint[60][61] fitness landscapes,[62] and neutral networks.[63]

Adaptive laboratory evolution of microbial proteomes

The natural amino acid composition of proteomes can be changed by global canonical amino acids substitutions with suitable noncanonical counterparts under the experimentally imposed selective pressure. For example, global proteome-wide substitutions of natural amino acids with fluorinated analogs have been attempted in Escherichia coli[64] and Bacillus subtilis.[65] A complete tryptophan substitution with thienopyrrole-alanine in response to 20899 UGG codons in Escherichia coli was reported in 2015 by Budisa and Söll.[66] The experimental evolution of microbial strains with a clear-cut accommodation of an additional amino acid is expected to be instrumental for widening the genetic code experimentally.[67] Directed evolution typically targets a particular gene for mutagenesis and then screens the resulting variants for a phenotype of interest, often independent of fitness effects, whereas adaptive laboratory evolution selects many genome-wide mutations that contribute to the fitness of actively growing cultures.[68]

See also

- Applications:

- Protein engineering

- Enzyme engineering

- Protein design

- Expanded genetic code

- Xenobiology

- Mutagenesis:

- Random mutagenesis

- Saturated mutagenesis

- Staggered extension process

- Selection and screening:

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Beyond directed evolution—semi-rational protein engineering and design". Current Opinion in Biotechnology 21 (6): 734–43. December 2010. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2010.08.011. PMID 20869867.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Directed Evolution: Past, Present and Future". AIChE Journal 59 (5): 1432–1440. May 2013. doi:10.1002/aic.13995. PMID 25733775.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "An extracellular Darwinian experiment with a self-duplicating nucleic acid molecule". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 58 (1): 217–24. July 1967. doi:10.1073/pnas.58.1.217. PMID 5231602. Bibcode: 1967PNAS...58..217M.

- ↑ "Experimental evolution of a new enzymatic function. II. Evolution of multiple functions for ebg enzyme in E. coli". Genetics 89 (3): 453–65. July 1978. doi:10.1093/genetics/89.3.453. PMID 97169.

- ↑ "Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface". Science 228 (4705): 1315–7. June 1985. doi:10.1126/science.4001944. PMID 4001944. Bibcode: 1985Sci...228.1315S.

- ↑ Chen, Keqin; Arnold, Frances H. (1991). "Enzyme Engineering for Nonaqueous Solvents: Random Mutagenesis to Enhance Activity of Subtilisin E in Polar Organic Media" (in En). Bio/Technology 9 (11): 1073–1077. doi:10.1038/nbt1191-1073. ISSN 0733-222X. PMID 1367624.

- ↑ Kim, Eun-Sung (2008-11-27). "Directed Evolution: A Historical Exploration into an Evolutionary Experimental System of Nanobiotechnology, 1965–2006" (in en). Minerva 46 (4): 463–484. doi:10.1007/s11024-008-9108-9. ISSN 0026-4695.

- ↑ "Methods for the directed evolution of proteins" (in En). Nature Reviews. Genetics 16 (7): 379–94. July 2015. doi:10.1038/nrg3927. PMID 26055155.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2018" (in en-US). https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2018/summary/.

- ↑ "Rational evolutionary design: the theory of in vitro protein evolution". Evolutionary Protein Design. 55. 2000. 79–160. doi:10.1016/s0065-3233(01)55003-2. ISBN 9780120342556.

- ↑ "Strategy and success for the directed evolution of enzymes". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 21 (4): 473–80. August 2011. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2011.05.003. PMID 21684150.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "In-vitro protein evolution by ribosome display and mRNA display". Journal of Immunological Methods 290 (1–2): 51–67. July 2004. doi:10.1016/j.jim.2004.04.008. PMID 15261571.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "How much of protein sequence space has been explored by life on Earth?". Journal of the Royal Society, Interface 5 (25): 953–6. August 2008. doi:10.1098/rsif.2008.0085. PMID 18426772.

- ↑ "Directed evolution of enzyme catalysts". Trends in Biotechnology 15 (12): 523–30. December 1997. doi:10.1016/s0167-7799(97)01138-4. PMID 9418307.

- ↑ "Developments in directed evolution for improving enzyme functions". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 143 (3): 212–23. December 2007. doi:10.1007/s12010-007-8003-4. PMID 18057449.

- ↑ "Triplet nucleotide removal at random positions in a target gene: the tolerance of TEM-1 beta-lactamase to an amino acid deletion". Nucleic Acids Research 33 (9): e80. May 2005. doi:10.1093/nar/gni077. PMID 15897323.

- ↑ "Rapid evolution of a protein in vitro by DNA shuffling". Nature 370 (6488): 389–91. August 1994. doi:10.1038/370389a0. PMID 8047147. Bibcode: 1994Natur.370..389S.

- ↑ "DNA shuffling of a family of genes from diverse species accelerates directed evolution". Nature 391 (6664): 288–91. January 1998. doi:10.1038/34663. PMID 9440693. Bibcode: 1998Natur.391..288C.

- ↑ "Iterative saturation mutagenesis (ISM) for rapid directed evolution of functional enzymes". Nature Protocols 2 (4): 891–903. 2007. doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.72. PMID 17446890.

- ↑ "What can we learn from fitness landscapes?". Current Opinion in Microbiology 21: 51–7. October 2014. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2014.08.001. PMID 25444121.

- ↑ "In vivo continuous directed evolution". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 24: 1–10. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.09.040. PMID 25461718.

- ↑ "Directed evolution: tailoring biocatalysts for industrial applications". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 33 (4): 365–78. December 2013. doi:10.3109/07388551.2012.716810. PMID 22985113.

- ↑ "Phage display: practicalities and prospects". Plant Molecular Biology 50 (6): 837–54. December 2002. doi:10.1023/A:1021215516430. PMID 12516857.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "New genotype–phenotype linkages for directed evolution of functional proteins". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 15 (4): 472–8. August 2005. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2005.07.006. PMID 16043338.

- ↑ "Intracellular detection and evolution of site-specific proteases using a genetic selection system". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 166 (5): 1340–54. March 2012. doi:10.1007/s12010-011-9522-6. PMID 22270548.

- ↑ "Evolutionary optimization of fluorescent proteins for intracellular FRET". Nature Biotechnology 23 (3): 355–60. March 2005. doi:10.1038/nbt1066. PMID 15696158.

- ↑ "The potential of microfluidic water-in-oil droplets in experimental biology". Molecular BioSystems 5 (12): 1392–404. December 2009. doi:10.1039/b907578j. PMID 20023716.

- ↑ "Rational design and engineering of therapeutic proteins". Drug Discovery Today 8 (5): 212–21. March 2003. doi:10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02610-2. PMID 12634013.

- ↑ "Rational protein design: developing next-generation biological therapeutics and nanobiotechnological tools". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 7 (3): 330–41. 27 October 2014. doi:10.1002/wnan.1310. PMID 25348497.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Evolution of a designed retro-aldolase leads to complete active site remodeling". Nature Chemical Biology 9 (8): 494–8. August 2013. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1276. PMID 23748672.

- ↑ "Improved biocatalysts by directed evolution and rational protein design". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 5 (2): 137–43. April 2001. doi:10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00182-4. PMID 11282339.

- ↑ Arnold, Frances; Georgiou, George (2003). Directed enzyme evolution: screening and selection methods. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press. ISBN 9781588292865. OCLC 52400248.

- ↑ Kaznatcheev, Artem (2019-05-01). "Computational Complexity as an Ultimate Constraint on Evolution" (in en). Genetics 212 (1): 245–265. doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302000. ISSN 0016-6731. PMID 30833289.

- ↑ Iram, Shamreen; Dolson, Emily; Chiel, Joshua; Pelesko, Julia; Krishnan, Nikhil; Güngör, Özenç; Kuznets-Speck, Benjamin; Deffner, Sebastian et al. (2020-08-24). "Controlling the speed and trajectory of evolution with counterdiabatic driving" (in en). Nature Physics 17: 135–142. doi:10.1038/s41567-020-0989-3. ISSN 1745-2481. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41567-020-0989-3.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Directed enzyme evolution: beyond the low-hanging fruit". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 22 (4): 406–12. August 2012. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2012.03.010. PMID 22579412.

- ↑ "Comparison of random mutagenesis and semi-rational designed libraries for improved cytochrome P450 BM3-catalyzed hydroxylation of small alkanes". Protein Engineering, Design & Selection 25 (4): 171–8. April 2012. doi:10.1093/protein/gzs004. PMID 22334757.

- ↑ "Iterative Saturation Mutagenesis: A Powerful Approach to Engineer Proteins by Systematically Simulating Darwinian Evolution". Directed Evolution Library Creation. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1179. 2014. pp. 103–28. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-1053-3_7. ISBN 978-1-4939-1052-6.

- ↑ "Natural diversity to guide focused directed evolution". ChemBioChem 11 (13): 1861–6. September 2010. doi:10.1002/cbic.201000284. PMID 20680978.

- ↑ "Thermostabilization of an esterase by alignment-guided focussed directed evolution". Protein Engineering, Design & Selection 23 (12): 903–9. December 2010. doi:10.1093/protein/gzq071. PMID 20947674.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Directed evolution drives the next generation of biocatalysts". Nature Chemical Biology 5 (8): 567–73. August 2009. doi:10.1038/nchembio.203. PMID 19620998.

- ↑ "Exploring protein fitness landscapes by directed evolution". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 10 (12): 866–76. December 2009. doi:10.1038/nrm2805. PMID 19935669.

- ↑ "Evolution of stability in a cold-active enzyme elicits specificity relaxation and highlights substrate-related effects on temperature adaptation". Journal of Molecular Biology 395 (1): 155–66. January 2010. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.026. PMID 19850050. https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/1009214.

- ↑ "Directed evolution converts subtilisin E into a functional equivalent of thermitase". Protein Engineering 12 (1): 47–53. January 1999. doi:10.1093/protein/12.1.47. PMID 10065710.

- ↑ "Optimizing bacteriophage engineering through an accelerated evolution platform". Scientific Reports 10 (1): 13981. 2020. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-70841-1. PMID 32814789.

- ↑ "Selection of phage antibodies by binding affinity. Mimicking affinity maturation". Journal of Molecular Biology 226 (3): 889–96. August 1992. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(92)90639-2. PMID 1507232.

- ↑ "Teaching old enzymes new tricks: engineering and evolution of glycosidases and glycosyl transferases for improved glycoside synthesis". Biochemistry and Cell Biology 86 (2): 169–77. April 2008. doi:10.1139/o07-149. PMID 18443630.

- ↑ "Directed evolution of a pyruvate aldolase to recognize a long chain acyl substrate". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 19 (21): 6447–53. November 2011. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2011.08.056. PMID 21944547.

- ↑ "Redesigning enzyme topology by directed evolution". Science 279 (5358): 1958–61. March 1998. doi:10.1126/science.279.5358.1958. PMID 9506949. Bibcode: 1998Sci...279.1958M.

- ↑ "Minimalist active-site redesign: teaching old enzymes new tricks". Angewandte Chemie 46 (18): 3212–36. 2007. doi:10.1002/anie.200604205. PMID 17450624.

- ↑ "Genetic analyses from ancient DNA". Annual Review of Genetics 38 (1): 645–79. 2004. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143214. PMID 15568989.

- ↑ "DNA damage and DNA sequence retrieval from ancient tissues". Nucleic Acids Research 24 (7): 1304–7. April 1996. doi:10.1093/nar/24.7.1304. PMID 8614634.

- ↑ "In the light of directed evolution: pathways of adaptive protein evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 Suppl 1 (Supplement_1): 9995–10000. June 2009. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901522106. PMID 19528653.

- ↑ "In vitro evolution goes deep". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (20): 8071–2. May 2011. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104843108. PMID 21551096. Bibcode: 2011PNAS..108.8071M.

- ↑ "In vitro evolution suggests multiple origins for the hammerhead ribozyme". Nature 414 (6859): 82–4. November 2001. doi:10.1038/35102081. PMID 11689947. Bibcode: 2001Natur.414...82S.

- ↑ "Evidence for de novo production of self-replicating and environmentally adapted RNA structures by bacteriophage Qbeta replicase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 72 (1): 162–6. January 1975. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.1.162. PMID 1054493. Bibcode: 1975PNAS...72..162S.

- ↑ "Aerial performance of Drosophila melanogaster from populations selected for upwind flight ability". The Journal of Experimental Biology 200 (Pt 21): 2747–55. November 1997. doi:10.1242/jeb.200.21.2747. PMID 9418031.

- ↑ "Experimental evolution of multicellularity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (5): 1595–600. January 2012. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115323109. PMID 22307617. Bibcode: 2012PNAS..109.1595R.

- ↑ "Genome evolution and adaptation in a long-term experiment with Escherichia coli". Nature 461 (7268): 1243–7. October 2009. doi:10.1038/nature08480. PMID 19838166. Bibcode: 2009Natur.461.1243B.

- ↑ "Evolutionary robustness of an optimal phenotype: re-evolution of lysis in a bacteriophage deleted for its lysin gene". Journal of Molecular Evolution 61 (2): 181–91. August 2005. doi:10.1007/s00239-004-0304-4. PMID 16096681. Bibcode: 2005JMolE..61..181H.

- ↑ "Environmental changes bridge evolutionary valleys". Science Advances 2 (1): e1500921. January 2016. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500921. PMID 26844293. Bibcode: 2016SciA....2E0921S.

- ↑ "How enzymes adapt: lessons from directed evolution". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 26 (2): 100–6. February 2001. doi:10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01755-2. PMID 11166567.

- ↑ "Surveying a local fitness landscape of a protein with epistatic sites for the study of directed evolution". Biopolymers 64 (2): 95–105. July 2002. doi:10.1002/bip.10126. PMID 11979520.

- ↑ "Thermodynamics of neutral protein evolution". Genetics 175 (1): 255–66. January 2007. doi:10.1534/genetics.106.061754. PMID 17110496.

- ↑ Bacher, J. M.; Ellington, A. D. (2001). "Selection and characterization of Escherichia coli variants capable of growth on an otherwise toxic tryptophan analogue". Journal of Bacteriology 183 (18): 5414–5425. doi:10.1128/jb.183.18.5414-5425.2001. PMID 11514527.

- ↑ Wong, J. T. (1983). "Membership mutation of the genetic code: Loss of fitness by tryptophan". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80 (20): 6303–6306. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.20.6303. PMID 6413975. Bibcode: 1983PNAS...80.6303W.

- ↑ Hoesl, M. G.; Oehm, S.; Durkin, P.; Darmon, E.; Peil, L.; Aerni, H.-R. (2015). "Chemical evolution of a bacterial proteome". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 54 (34): 10030–10034. doi:10.1002/anie.201502868. PMID 26136259. NIHMSID: NIHMS711205

- ↑ Agostini, F.; Völler, J-S.; Koksch, B.; Acevedo-Rocha, C. G.; Kubyshkin, V.; Budisa, N. (2017). "Biocatalysis with Unnatural Amino Acids: Enzymology Meets Xenobiology". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 56 (33): 9680–9703. doi:10.1002/anie.201610129. PMID 28085996.

- ↑ Sandberg, T. E.; Salazar, M. J.; Weng, L. L.; Palsson, B. O.; Kubyshkin, V.; Feist, A. M. (2019). "The emergence of adaptive laboratory evolution as an efficient tool for biological discovery and industrial biotechnology". Metab Eng 56: 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2019.08.004. PMID 31401242.

External links

- Research groups

- The Dan Tawfik Research Group

- The Ulrich Schwaneberg Research Group

- The Frances Arnold Research Group

- The Huimin Zhao Research Group

- The Manfred Reetz Research Group

- The Donald Hilvert Group

- The Darren Hart Research Group

- The Chang Liu Research Group

- The David Liu Research Group

- The Douglas Clark Research Group

- The Paul Dalby Research Group

- The Ned Budisa Research Group

- SeSaM-Biotech – Directed Evolution

- Prof. Reetz explains the principle of Directed Evolution

- Codexis, Inc.

|