Biology:Glutaminolysis

Glutaminolysis (glutamine + -lysis) is a series of biochemical reactions by which the amino acid glutamine is lysed to glutamate, aspartate, CO2, pyruvate, lactate, alanine and citrate.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21]

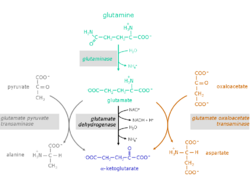

The glutaminolytic pathway

Glutaminolysis partially recruits reaction steps from the citric acid cycle and the malate-aspartate shuttle.

Reaction steps from glutamine to α-ketoglutarate

The conversion of the amino acid glutamine to α-ketoglutarate takes place in two reaction steps:

1. Hydrolysis of the amino group of glutamine yielding glutamate and ammonium. Catalyzing enzyme: glutaminase (EC 3.5.1.2)

2. Glutamate can be excreted or can be further metabolized to α-ketoglutarate.

For the conversion of glutamate to α-ketoglutarate three different reactions are possible:

Catalyzing enzymes:

- glutamate dehydrogenase (GlDH), EC 1.4.1.2

- glutamate pyruvate transaminase (GPT), also called alanine transaminase (ALT), EC 2.6.1.2

- glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase (GOT), also called aspartate transaminase (AST), EC 2.6.1.1 (component of the malate aspartate shuttle)

Recruited reaction steps of the citric acid cycle and malate aspartate shuttle

- α-ketoglutarate + NAD+ + CoASH → succinyl-CoA + NADH+H+ + CO2

catalyzing enzyme: α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex

- succinyl-CoA + GDP + Pi → succinate + GTP

catalyzing enzyme: succinyl-CoA-synthetase, EC 6.2.1.4

- succinate + FAD → fumarate + FADH2

catalyzing enzyme: succinate dehydrogenase, EC 1.3.5.1

- fumarate + H2O → malate

catalyzing enzyme: fumarase, EC 4.2.1.2

- malate + NAD+ → oxaloacetate + NADH + H+

catalyzing enzyme: malate dehydrogenase, EC 1.1.1.37 (component of the malate aspartate shuttle)

- oxaloacetate + acetyl-CoA + H2O → citrate + CoASH

catalyzing enzyme: citrate synthase, EC 2.3.3.1

Reaction steps from malate to pyruvate and lactate

The conversion of malate to pyruvate and lactate is catalyzed by

- NAD(P) dependent malate decarboxylase (malic enzyme; EC 1.1.1.39 and 1.1.1.40) and

- lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; EC 1.1.1.27)

according to the following equations:

- malate + NAD(P)+→ pyruvate + NAD(P)H + H+ + CO2

- pyruvate + NADH + H+ → lactate + NAD+

Intracellular compartmentalization of the glutaminolytic pathway

The reactions of the glutaminolytic pathway take place partly in the mitochondria and to some extent in the cytosol (compare the metabolic scheme of the glutaminolytic pathway).

Glutaminolysis: an important energy source in tumor cells

Glutaminolysis takes place in all proliferating cells,[22] such as lymphocytes, thymocytes, colonocytes, adipocytes and especially in tumor cells.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][10][11][12][13][14][16][18][19][23] Glutaminolysis has been targeted for therapeutic purposes.[21] In tumor cells the citric acid cycle is truncated due to an inhibition of the enzyme aconitase (EC 4.2.1.3) by high concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[24][25] Aconitase catalyzes the conversion of citrate to isocitrate. On the other hand, tumor cells over express phosphate dependent glutaminase and NAD(P)-dependent malate decarboxylase,[9][26][27][28][29] which in combination with the remaining reaction steps of the citric acid cycle from α-ketoglutarate to citrate impart the possibility of a new energy producing pathway, the degradation of the amino acid glutamine to glutamate, aspartate, pyruvate CO2, lactate and citrate.

Besides glycolysis in tumor cells glutaminolysis is another main pillar for energy production. High extracellular glutamine concentrations stimulate tumor growth and are essential for cell transformation.[28][30] On the other hand, a reduction of glutamine correlates with phenotypical and functional differentiation of the cells.[31]

Energy efficacy of glutaminolysis in tumor cells

- one ATP by direct phosphorylation of GDP

- two ATP from oxidation of FADH2

- three ATP at a time for the NADH + H+ produced within the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase reaction, the malate dehydrogenase reaction and the malate decarboxylase reaction.

Due to low glutamate dehydrogenase and glutamate pyruvate transaminase activities, in tumor cells the conversion of glutamate to alpha-ketoglutarate mainly takes place via glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase.[5][32]

Advantages of glutaminolysis in tumor cells

- Glutamine is the most abundant amino acid in the plasma and an additional energy source in tumor cells especially when glycolytic energy production is low due to a high amount of the dimeric form of M2-PK.

- Glutamine and its degradation products glutamate and aspartate are precursors for nucleic acid and serine synthesis.

- Glutaminolysis is insensitive to high concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS).[33]

- Due to the truncation of the citric acid cycle the amount of acetyl-CoA infiltrated in the citric acid cycle is low and acetyl-CoA is available for de novo synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol. The fatty acids can be used for phospholipid synthesis or can be released.[34]

- Fatty acids represent an effective storage vehicle for hydrogen. Therefore, the release of fatty acids is an effective way to get rid of cytosolic hydrogen produced within the glycolytic glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; EC 1.2.1.9) reaction.[35]

- Glutamate and fatty acids are immunosuppressive. The release of both metabolites may protect tumor cells from immune attacks.[36][37][38]

- It has been discussed that the glutamate pool may drive the endergonic uptake of other amino acids by system ASC.[17]

- Glutamine can be converted to citrate without NADH production, uncoupling NADH production from biosynthesis.[22]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Krebs, HA; Bellamy D (1960). "The interconversion of glutamic acid and aspartic acid in respiring tissues". The Biochemical Journal 75 (3): 523–529. doi:10.1042/bj0750523. PMID 14411856.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Reitzer, LJ; Wice BM; Kennell D (1979). "Evidence that glutamine, not sugar, is the major energy source for cultured HeLa-cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 254 (8): 2669–2676. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)30124-2. PMID 429309.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Zielke, HR; Sumbilla CM; Sevdalian DA; Hawkins RL; Ozand PT (1980). "Lactate: a major product of glutamine metabolism by human diploid fibroblasts". Journal of Cellular Physiology 104 (3): 433–441. doi:10.1002/jcp.1041040316. PMID 7419614.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Mc Keehan, WL (1982). "Glycolysis, glutaminolysis and cell proliferation". Cell Biology International Reports 6 (7): 635–650. doi:10.1016/0309-1651(82)90125-4. PMID 6751566.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Moreadith RW, RW; Lehninger AL (1984). "The pathways of glutamate and glutamine oxidation by tumor cell mitochondria". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 259 (10): 6215–6221. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(20)82128-0. PMID 6144677.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Zielke, HR; Zielke CL; Ozand PT (1984). "Glutamine: a major energy source for cultured mammalian cells". Federation Proceedings 43 (1): 121–125. PMID 6690331.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Eigenbrodt, E; Fister P; Reinacher M (1985). "New perspectives on carbohydrate metabolism in tumor cells". Regulation of Carbohydrate Metabolism. 2. pp. 141–179. ISBN 978-0-8493-5263-8.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lanks, KW (1987). "End products of glucose and glutamine metabolism by L929 cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 262 (21): 10093–10097. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)61081-6. PMID 3611053.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Board, M; Humm S; Newsholme EA (1990). "Maximum activities of key enzymes of glycolysis, glutaminolysis, pentose phosphate pathway and tricarboxylic acid cycle in normal, neoplastic and suppressed cells". The Biochemical Journal 265 (2): 503–509. doi:10.1042/bj2650503. PMID 2302181.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Medina, MA; Nunez de Castro I (1990). "Glutaminolysis and glycolysis interactions in proliferant cells". International Journal of Biochemistry 22 (7): 681–683. doi:10.1016/0020-711X(90)90001-J. PMID 2205518.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Goossens, V; Grooten J; Fiers W (1996). "The oxidative metabolism of glutamine. A modulator of reactive oxygen intermediate-mediated cytotoxicity of tumor necrosis factor in L929 fibrosarcoma cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 271 (1): 192–196. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.1.192. PMID 8550558.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mazurek, S; Michel A; Eigenbrodt E (1997). "Effect of extracellular AMP on cell proliferation and metabolism of breast cancer cell lines with high and low glycolytic rates". Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 (8): 4941–4952. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.8.4941. PMID 9030554.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Eigenbrodt, E; Kallinowski F; Ott M; Mazurek S; Vaupel P (1998). "Pyruvate kinase and the interaction of amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism in solid tumors". Anticancer Research 18 (5A): 3267–3274. PMID 9858894.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Piva, TJ; McEvoy-Bowe E (1998). "Oxidation of glutamine in HeLa cells: role and control of truncated TCA cycles in tumour mitochondria". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 68 (2): 213–225. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19980201)68:2<213::AID-JCB8>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 9443077.

- ↑ Mazurek, S; Eigenbrodt E; Failing K; Steinberg P (1999). "Alterations in the glycolytic and glutaminolytic pathways after malignant transformation of rat liver oval cells". Journal of Cellular Physiology 181 (1): 136–146. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199910)181:1<136::AID-JCP14>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 10457361.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Mazurek, S; Zwerschke W; Jansen-Dürr P; Eigenbrodt E (2001). "Effects of the human papilloma virus HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein on glycolysis and glutaminolysis: role of pyruvate kinase type M2 and the glycolytic enzyme complex". Biochemical Journal 356 (Pt 1): 247–256. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3560247. PMID 11336658.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Aledo, JC (2004). "Glutamine breakdown in rapidly dividing cells: waste or investment ?". BioEssays 26 (7): 778–785. doi:10.1002/bies.20063. PMID 15221859.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Rossignol, R; Gilkerson R; Aggeler R; Yamagata K; Remington SJ; Capaldi RA (2004). "Energy substrate modulates mitochondrial structure and oxidative capacity in cancer cells". Cancer Research 64 (3): 985–993. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1101. PMID 14871829.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Mazurek, S (2007). "Tumor cell energetic metabolome". Molecular System Bioenergetics. pp. 521–540. ISBN 978-3-527-31787-5.

- ↑ DeBerardinis, RJ; Sayed N; Ditsworth D; Thompson CB (2008). "Brick by brick: metabolism and tumor growth". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 18 (1): 54–61. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2008.02.003. PMID 18387799.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Enhancing the efficacy of glutamine metabolism inhibitors in cancer therapy". Trends in Cancer. https://www.cell.com/trends/cancer/fulltext/S2405-8033(21)00083-2.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Fernandez-de-Cossio-Diaz, Jorge; Vazquez, Alexei (2017-10-18). "Limits of aerobic metabolism in cancer cells" (in En). Scientific Reports 7 (1): 13488. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-14071-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 29044214. Bibcode: 2017NatSR...713488F.

- ↑ Wolfrom, C; Kadhom N; Polini G; Poggi J; Moatti N; Gautier M (1989). "Glutamine dependency of human skin fibroblasts: modulation of hexoses". Experimental Cell Research 183 (2): 303–318. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(89)90391-1. PMID 2767153.

- ↑ Gardner, PR; Raineri I; Epstein LB; White CW (1995). "Superoxide radical and iron modulate aconitase activity in mammalian cells". Journal of Biological Chemistry 270 (22): 13399–13405. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.22.13399. PMID 7768942.

- ↑ Kim, KH; Rodriguez AM; Carrico PM; Melendez JA (2001). "Potential mechanisms for the inhibition of tumor cell growth by manganese superoxide dismutase". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 3 (3): 361–373. doi:10.1089/15230860152409013. PMID 11491650.

- ↑ Matsuno, T; Goto I (1992). "Glutaminase and glutamine synthetase activities in human cirrhotic liver and hepatocellular carcinoma". Cancer Research 52 (5): 1192–1194. PMID 1346587.

- ↑ "Phosphate-activated glutaminase expression during tumor development". FEBS Letters 341 (1): 39–42. 1994. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)80236-X. PMID 8137919.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Inhibition of glutaminase expression by antisense mRNA decreases growth and tumourigenicity of tumour cells". Biochemical Journal 348 (2): 257–261. 2000. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3480257. PMID 10816417.

- ↑ Mazurek, S; Grimm H; Oehmke M; Weisse G; Teigelkamp S; Eigenbrodt E (2000). "Tumor M2-PK and glutaminolytic enzymes in the metabolic shift of tumor cells". Anticancer Research 20 (6D): 5151–5154. PMID 11326687.

- ↑ Turowski, GA; Rashid Z; Hong F; Madri JA; Basson MD (1994). "Glutamine modulates phenotype and stimulates proliferation in human colon cancer cell lines". Cancer Research 54 (22): 5974–5980. PMID 7954430.

- ↑ Spittler, A; Oehler R; Goetzinger P; Holzer S; Reissner CM; Leutmezer J; Rath V; Wrba F et al. (1997). "Low glutamine concentrations induce phenotypical and functional differentiation of U937 myelomonocytic cells". The Journal of Nutrition 127 (11): 2151–2157. doi:10.1093/jn/127.11.2151. PMID 9349841.

- ↑ Matsuno, T (1991). "Pathway of glutamate oxidation and its regulation in HuH13 line of human hepatoma cells". Journal of Cellular Physiology 148 (2): 290–294. doi:10.1002/jcp.1041480215. PMID 1679060.

- ↑ Stephen J. Ralph; Rafael Moreno-Sánchez; Jiri Neuzil; Sara Rodríguez-Enríquez (24 August 2011). "Inhibitors of Succinate: Quinone Reductase/Complex II Regulate Production of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species and Protect Normal Cells from Ischemic Damage but Induce Specific Cancer Cell Death". Pharmaceutical Research 28 (2695): 2695–2730. doi:10.1007/s11095-011-0566-7. PMID 21863476. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11095-011-0566-7. Retrieved 1 November 2021. "Unlike aconitase, glutaminolysis is relatively insensitive to ROS levels.".

- ↑ Parlo, RA; Coleman PS (1984). "Enhanced rate of citrate export from cholesterol-rich hepatoma mitochondria. The truncated Krebs cycle and other metabolic ramifications of mitochondrial membrane cholesterol". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 259 (16): 9997–10003. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)90917-8. PMID 6469976.

- ↑ Mazurek, S; Grimm H; Boschek CB; Vaupel P; Eigenbrodt E (2002). "Pyruvate kinase type M2: a crossroad in the tumor metabolome". The British Journal of Nutrition 87: S23–S29. doi:10.1079/BJN2001455. PMID 11895152.

- ↑ Eck, HP; Drings P; Dröge W (1989). "Plasma glutamate levels, lymphocyte reactivity and death in patients with bronchial carcinoma". Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 115 (6): 571–574. doi:10.1007/BF00391360. PMID 2558118.

- ↑ Grimm, H; Tibell A; Norrlind B; Blecher C; Wilker S; Schwemmle K (1994). "Immunoregulation by parental lipids: impact of the n-3 to n-6 fatty acid ratio". Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 18 (5): 417–421. doi:10.1177/0148607194018005417. PMID 7815672.

- ↑ Jiang, WG; Bryce RP; Hoorobin DF (1998). "Essential fatty acids: molecular and cellular basis of their anti-cancer action and clinical implications". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 27 (3): 179–209. doi:10.1016/S1040-8428(98)00003-1. PMID 9649932.

External links

|