Biology:List of canids

Canidae is a family of mammals in the order Carnivora, which includes domestic dogs, wolves, coyotes, foxes, jackals, dingoes, and many other extant and extinct dog-like mammals. A member of this family is called a canid; all extant species are a part of a single subfamily, Caninae, and are called canines. They are found on all continents except Antarctica, having arrived independently or accompanied human beings over extended periods of time. Canids vary in size, including tails, from the 2 meter (6 ft 7 in) wolf to the 46 cm (18 in) fennec fox. Population sizes range from the Falkland Islands wolf, extinct since 1876, to the domestic dog, which has a worldwide population of over 1 billion.[1] The body forms of canids are similar, typically having long muzzles, upright ears, teeth adapted for cracking bones and slicing flesh, long legs, and bushy tails.[2] Most species are social animals, living together in family units or small groups and behaving cooperatively. Typically, only the dominant pair in a group breeds, and a litter of young is reared annually in an underground den. Canids communicate by scent signals and vocalizations.[3] One canid, the domestic dog, entered into a partnership with humans at least 14,000 years ago and today remains one of the most widely kept domestic animals.[4]

The 13 extant genera and 37 species of Caninae are primarily split into two tribes: Canini, which includes 11 genera and 19 species, comprising the wolf-like Canina subtribe and the South American Cerdocyonina subtribe; and Vulpini, the fox-like canids, comprising 3 genera and 15 species. Not included in either tribe is the Urocyon genus, which includes 2 species, mainly comprising the gray fox and believed to be basal to the family. Additionally, one genus in Canini, Dusicyon, was composed of two recently extinct species, with the South American fox going extinct around 400 years ago and the Falkland Islands wolf going extinct in 1876.

In addition to the extant Caninae, Canidae comprises two extinct subfamilies designated as Hesperocyoninae and Borophaginae. Extinct species have also been placed into Caninae, in both extant and extinct genera; at least 80 extinct Caninae species have been found, as well as over 70 species in Borophaginae and nearly 30 in Hesperocyoninae, though due to ongoing research and discoveries the exact number and categorization is not fixed. The earliest canids found belong to Hesperocyoninae, and are believed to have diverged from the existing Caniformia suborder around 37 million years ago.[5]

Conventions

Conservation status codes listed follow the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Range maps are provided wherever possible; if a range map is not available, a description of the canid's range is provided. Ranges are based on the IUCN Red List for that species, unless otherwise noted. All extinct species (or subspecies) listed alongside extant species went extinct after 1500 CE, and are indicated by a dagger symbol:

Classification

The family Canidae consists of 37 extant species belonging to 12 genera and divided into 194 extant subspecies, as well the extinct genus Dusicyon, comprising two extinct species, and 13 extinct wolf subspecies, which are the only canid species to go extinct since prehistoric times. This does not include hybrid species (such as wolfdogs or coywolfs) or extinct prehistoric species (such as the dire wolf or Epicyon). Modern molecular studies indicate that the 13 genera can be grouped into 3 tribes or clades.

Subfamily Caninae

- Tribe Canini

- Subtribe Canina

- Subtribe Cerdocyonina

- Genus Atelocynus: one species

- Genus Cerdocyon: one species

- Genus Chrysocyon: one species

- Genus Dusicyon

: two species

: two species - Genus Lycalopex: six species

- Genus Speothos: one species

- Tribe Vulpini

- Genus Nyctereutes: two species

- Genus Otocyon: one species

- Genus Vulpes: twelve species

- Genus Urocyon: two species

Canids

The following classification is based on the taxonomy described by Mammal Species of the World (2005), with augmentation by generally accepted proposals made since using molecular phylogenetic analysis, such as the promotion of the African golden wolf to a separate species from the golden jackal, and splitting out the Lupulella genus from Canis. Range maps are based on IUCN range data. There are several additional proposals which are disputed, such as the promotion of the red wolf and eastern wolf as species from subspecies of the wolf, which are marked with a "(debated)" tag.

Subfamily Caninae

Tribe Canini

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-eared dog | A. microtis Cabrera, 1940 Two subspecies

|

Western Amazon rainforest in South America

|

Size: 72–100 cm (28–39 in) long, plus 24–35 cm (9–14 in) tail[6] Habitat: Wetlands, forest, and savanna[7] Diet: Primarily eats fish, insects, and small mammals, as well as fruit, birds, and crabs[7][8] |

NT

|

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African wolf | C. lupaster Hemprich and Ehrenberg, 1832 Six subspecies

|

North and northeastern Africa

|

Size: 100 cm (39 in) long, plus 20 cm (8 in) tail[9] Habitat: Grassland, shrubland, and savanna[10] Diet: Primarily eats wild boar and livestock, as well as other mammals and fruit[10][11] |

LC

|

| Coyote | C. latrans Say, 1823 Nineteen subspecies

|

North America

|

Size: 100–135 cm (39–53 in) long, plus 40 cm (16 in) tail[12] Habitat: Forest, desert, shrubland, and grassland[13] Diet: Eats a wide variety of foods, including both small and large mammals, fruit, and insects[13] |

LC |

| Dog | C. familiaris Linnaeus, 1758 |

Worldwide | Size: Varies by breed Habitat: Domesticated Diet: Varied |

NE

|

| Ethiopian wolf | C. simensis Rüppell, 1840 Two subspecies

|

Ethiopian Highlands

|

Size: 84–100 cm (33–39 in) long, plus 27–40 cm (11–16 in) tail[15] Habitat: Inland wetlands, grassland, shrubland, and rocky areas[16] Diet: Primarily eats rodents as well as small mammals[16][17] |

EN

|

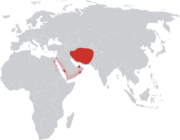

| Golden jackal | C. aureus Linnaeus, 1758 Seven subspecies

|

Eastern Europe, Middle East, and southern Asia

|

Size: 60–132 cm (24–52 in) long, plus 20–30 cm (8–12 in) tail[18] Habitat: Forest, grassland, shrubland, and savanna[19] Diet: Eats a wide variety of foods, including small to large mammals, birds, fish, fruit, and insects[19][18] |

LC

|

| Wolf | C. lupus Linnaeus, 1758 37 subspecies

|

Eurasia and northern North America

|

Size: 105–160 cm (41–63 in) long, plus 29–50 cm (11–20 in) tail[20] Habitat: Forest, desert, rocky areas, shrubland, grassland, and inland wetlands[21] Diet: Primarily eats large ungulates, as well as small animals, carrion, and berries[21][22] |

LC |

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crab-eating fox | C. thous Linnaeus, 1766 Five subspecies

|

Eastern and northern South America

|

Size: 64 cm (25 in) long, plus 28 cm (11 in) tail[24] Habitat: Forest, savanna, shrubland, grassland, and inland wetlands[25] Diet: Primarily eats crabs and insects, as well as rodents, birds, turtles, eggs, fruit, and carrion[24][25] |

LC

|

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maned wolf | C. brachyurus Illiger, 1815 |

Central South America

|

Size: 100–130 cm (39–51 in) long, plus 45 cm (18 in) tail[26][27] Habitat: Forest, wetlands, grassland, shrubland, and savanna[28] Diet: Primarily eats fruit, arthropods, and small and medium vertebrates[28] |

NT

|

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dhole | C. alpinus Pallas, 1811 Three subspecies

|

Southeast Asia

|

Size: 90 cm (35 in) long, plus 40–45 cm (16–18 in) tail[29] Habitat: Forest, grassland, and shrubland[30] Diet: Primarily eats ungulates, as well as small rodents and hares[30] |

EN

|

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Falkland Islands wolf |

D. australis Kerr, 1792 |

Falkland Islands at tip of South America

|

Size: Unknown Habitat: Grassland and shrubland[31] Diet: Unknown[31] |

EX |

| South American fox

|

D. avus Burmeister, 1866 |

Southern South America | Size: Unknown Habitat: Grassland and shrubland[32] Diet: Unknown[32] |

EX |

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black-backed jackal | L. mesomelas Schreber, 1775 Two subspecies

|

Southern Africa and eastern Africa

|

Size: 60–95 cm (24–37 in) long, plus 16–40 cm (6–16 in) tail[34] Habitat: Marine intertidal, forest, desert, grassland, shrubland, and savanna[35] Diet: Primarily eats small to medium-sized mammals and birds[35][36] |

LC

|

| Side-striped jackal | L. adustus Sundevall, 1847 Seven subspecies

|

Central Africa

|

Size: 69–81 cm (27–32 in) long, plus 30–41 cm (12–16 in) tail[37] Habitat: Forest, shrubland, savanna, grassland, and inland wetlands[38] Diet: Primarily eats small to medium-sized mammals and fruit, as well as birds, insects, grass, and carrion[38][39] |

LC |

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culpeo | L. culpeo Molina, 1782 Six subspecies

|

Western South America

|

Size: 95–132 cm (37–52 in) long, plus 32–44 cm (13–17 in) tail[41] Habitat: Forest, rocky areas, grassland, shrubland, and savanna[42] Diet: Primarily eats rodents and lagomorphs, as well as livestock and guanacos[42][43] |

LC

|

| Darwin's fox | L. fulvipes Martin, 1837 |

Limited areas in southern Chile

|

Size: 48–59 cm (19–23 in) long, plus 18–26 cm (7–10 in) tail[44] Habitat: Forest and shrubland[45] Diet: Primarily eats small mammals, insects, crabs, and fruit[44][45] |

EN

|

| Hoary fox | L. vetulus Lund, 1842 |

South-central Brazil

|

Size: 49–71 cm (19–28 in) long, plus 25–38 cm (10–15 in) tail[44] Habitat: Savanna[46] Diet: Primarily eats insects, as well as small rodents, birds, reptiles, and fruit[44][46] |

LC

|

| Pampas fox | L. gymnocercus Waldheim, 1814 Five subspecies

|

Southern South America

|

Size: 51–74 cm (20–29 in) long, plus 25–41 cm (10–16 in) tail[44] Habitat: Forest, shrubland, and savanna[47] Diet: Primarily eats small rodents, hares, birds, insects, and fruit, as well as carrion[44][47] |

LC

|

| Sechuran fox | L. sechurae Thomas, 1900 |

Sechura Desert in southwestern Ecuador and northwestern Peru

|

Size: 50–78 cm (20–31 in) long, plus 27–34 cm (11–13 in) tail[44] Habitat: Forest, desert, grassland, and shrubland[48] Diet: Primarily eats fruit and seeds, as well as small rodents, birds, reptiles, insects, scorpions, and carrion[44][48] |

NT |

| South American gray fox | L. griseus Gray, 1837 |

Southern South America

|

Size: 50–66 cm (20–26 in) long, plus 12–34 cm (5–13 in) tail[44] Habitat: Forest, grassland, and shrubland[50] Diet: Primarily eats small rodents, hares, and carrion[44][50] |

LC

|

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African wild dog | L. pictus Temminck, 1820 Five subspecies

|

Scattered areas of Africa

|

Size: 76–112 cm (30–44 in) long, plus 30–42 cm (12–17 in) tail[44] Habitat: Forest, grassland, shrubland, savanna, and desert[51] Diet: Primarily eats medium-sized antelope[51] |

EN

|

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bush dog | S. venaticus Lund, 1842 Three subspecies

|

Northern South America

|

Size: 57–75 cm (22–30 in) long, plus 12–15 cm (5–6 in) tail[52] Habitat: Shrubland, forest, grassland, and savanna[53] Diet: Primarily eats small and medium mammals, as well as birds, reptiles, and fruit[53] |

NT |

Tribe Vulpini

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common raccoon dog | N. procyonoides Gray, 1834 Four subspecies

|

Mainland Eastern Asia, introduced to Central and Eastern Europe (note: map includes range of N. viverrinus)

|

Size: 49–71 cm (19–28 in) long, plus 15–23 cm (6–9 in) tail[44] Habitat: Forest, grassland, and shrubland[55] Diet: Primarily eats insects, rodents, amphibians, birds, fish, and reptiles, as well as fruit, nuts, and berries[55] |

LC |

| Japanese raccoon dog | N. viverrinus[57] Temminck, 1838 |

Japan | Size: 49–71 cm (19–28 in) long, plus 15–23 cm (6–9 in) tail[44] Habitat: Forest, grassland, and shrubland[55] Diet: Primarily eats insects, rodents, amphibians, birds, fish, and reptiles, as well as fruit, nuts, and berries[55] |

NE

|

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bat-eared fox | O. megalotis Desmarest, 1822 Two subspecies

|

Southern and Eastern Africa

|

Size: 46–61 cm (18–24 in) long, plus 23–34 cm (9–13 in) tail[44] Habitat: Grassland, shrubland, and savanna[58] Diet: Primarily eats harvester termites as well as other arthropods[58] |

LC

|

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arctic fox | V. lagopus Linnaeus, 1758 Five subspecies

|

Arctic North America and Eurasia

|

Size: 50–75 cm (20–30 in) long, plus 25–43 cm (10–17 in) tail[44] Habitat: Grassland[59] Diet: Primarily eats lemmings, as well as other rodents, birds, and reindeer[59] |

LC

|

| Bengal fox | V. bengalensis Shaw, 1800 |

India

|

Size: 39–58 cm (15–23 in) long, plus 25–32 cm (10–13 in) tail[44] Habitat: Grassland and shrubland[60] Diet: Primarily eats arthropods, rodents, reptiles, fruit, and birds[60] |

LC

|

| Blanford's fox | V. cana Blanford, 1877 |

The Middle East and Central Asia

|

Size: 34–47 cm (13–19 in) long, plus 26–36 cm (10–14 in) tail[44] Habitat: Desert and rocky areas[61] Diet: Primarily eats fruit and insects[61] |

LC

|

| Cape fox | V. chama A Smith, 1833 |

Southern Africa

|

Size: 45–61 cm (18–24 in) long, plus 25–41 cm (10–16 in) tail[44] Habitat: Rocky areas, grassland, shrubland, and savanna[62] Diet: Primarily eats fruit and insects[62] |

LC

|

| Corsac fox | V. corsac Linnaeus, 1768 Three subspecies

|

Central Asia

|

Size: 45–60 cm (18–24 in) long, plus 19–34 cm (7–13 in) tail[44] Habitat: Desert, grassland, and shrubland[63] Diet: Primarily eats insects and small rodents[63] |

LC

|

| Fennec fox | V. zerda Zimmermann, 1780 |

Northern Africa

|

Size: 33–40 cm (13–16 in) long, plus 13–23 cm (5–9 in) tail[44] Habitat: Desert and marine coastal/supratidal[64] Diet: Primarily eats rodents, insects, birds, eggs, and rabbits[64] |

LC

|

| Kit fox | V. macrotis Merriam, 1888 Two subspecies

|

Western North America

|

Size: 46–54 cm (18–21 in) long, plus 25–34 cm (10–13 in) tail[44] Habitat: Shrubland, savanna, and grassland[65] Diet: Primarily eats rodents, rabbits, invertebrates, birds, lizards, and snakes[65] |

LC

|

| Pale fox | V. pallida Cretzschmar, 1827 Five subspecies

|

Upper middle Africa

|

Size: 38–55 cm (15–22 in) long, plus 23–29 cm (9–11 in) tail[44] Habitat: Desert, grassland, shrubland, and savanna[66] Diet: Primarily eats plants and berries as well as rodents, reptiles, and insects[66] |

LC

|

| Rüppell's fox | V. rueppellii Schinz, 1825 |

Northern Africa and the Middle East

|

Size: 35–56 cm (14–22 in) long, plus 25–39 cm (10–15 in) tail[44] Habitat: Desert, shrubland, and marine coastal/supratidal[67] Diet: Primarily eats small mammals, lizards, birds, and insects, as well as fruit and succulents[67] |

LC

|

| Red fox | V. vulpes Linnaeus, 1758 44 subspecies

|

North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia

|

Size: 62–72 cm (24–28 in) long, plus 40 cm (16 in) tail[68] Habitat: Shrubland, grassland, inland wetlands, forest, and desert[69] Diet: Primarily eats small rodents, as well as birds, larger mammals, reptiles, insects, and fish[69] |

LC

|

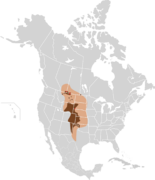

| Swift fox | V. velox Say, 1823 |

Western grasslands of North America

|

Size: 48–54 cm (19–21 in) long, plus 25–34 cm (10–13 in) tail[44] Habitat: Grassland[70] Diet: Primarily eats rabbits, mice, ground squirrels, birds, insects and lizards, as well as grasses and fruit[70] |

LC

|

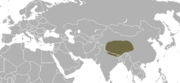

| Tibetan fox | V. ferrilata Hodgson, 1842 |

High plateaus in Nepal and western China

|

Size: 49–70 cm (19–28 in) long, plus 22–29 cm (9–11 in) tail[44] Habitat: Desert, rocky areas, grassland, and shrubland[71] Diet: Primarily eats pikas, as well as carrion and other small mammals[71] |

LC

|

Urocyon

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray fox | U. cinereoargenteus Schreber, 1775 Sixteen subspecies

|

North America and Central America

|

Size: 53–66 cm (21–26 in) long, plus 28–44 cm (11–17 in) tail[44] Habitat: Forest and shrubland[72] Diet: Primarily eats rabbits, voles, shrews, and birds, as well as insects and fruit[72] |

LC

|

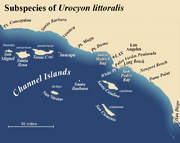

| Island fox | U. littoralis Baird, 1857 Six subspecies

|

Channel Islands of California

|

Size: 46–63 cm (18–25 in) long, plus 12–32 cm (5–13 in) tail[44] Habitat: Marine intertidal, forest, grassland, and shrubland[73] Diet: Primarily eats fruit, insects, birds, eggs, crabs, lizards, and small mammals[73] |

NT

|

Prehistoric canids

In addition to extant canids, a number of prehistoric species have been discovered and classified as a part of Canidae. Morphogenic and molecular phylogenic research has placed them within the extant subfamily Caninae as well as the extinct subfamilies Hesperocyoninae and Borophaginae. Within Caninae, prehistoric species have been placed into both extant genera and separate extinct genera.

The generally accepted classification of extinct canid species is primarily based for Hesperocyoninae on work by Xiaoming Wang, curator of terrestrial mammals at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County,[5] and on work by Wang and zoologists Richard H. Tedford and Beryl E. Taylor for Borophaginae and Caninae.[74][75][76] The species and classifications listed below are all from these works; exceptions due to more recently-described species are also listed with citations. Not all of these classifications are universally accepted, and alternate classifications for species are noted below. Where available, the approximate time period the species was extant is given in millions of years before the present (Mya), based on data from the Paleobiology Database. All listed species are extinct; where a genus, subtribe, or tribe within Caninae comprises only extinct species, it is indicated with a dagger symbol ![]() .

.

Subfamily Caninae

- Tribe Canini

- Subtribe Canina

- Genus Aenocyon

(1.8–0.012 Mya)

(1.8–0.012 Mya)

- A. dirus (Dire wolf) (1.8–0.012 Mya)

- Genus Canis

- C. antonii

- C. apolloniensis (2.6–0.78 Mya)[77]

- C. armbrusteri (Armbruster's wolf) (1.8–0.012 Mya)

- C. arnensis (Arno River dog) (2.6–0.78 Mya)

- C. brevicephalus

- C. cedazoensis (1.8–0.3 Mya)

- C. chihliensis

- C. cipio[lower-alpha 4]

- C. edwardii (23–0.78 Mya)

- C. etruscus (Etruscan wolf) (2.6–0.13 Mya)

- C. ferox (4.9–2.6 Mya)

- C. gezi

- C. leilhardi

- C. lepophagus (4.9–0.012 Mya)

- C. longdanensis

- C. mosbachensis (Mosbach wolf) (2.6–0.13 Mya)

- C. nehringi

- C. othmani[78]

- C. palmidens

- C. variabilis

- Genus Cynotherium

(0.13–0.012 Mya)

(0.13–0.012 Mya)

- C. sardous (Sardinian dhole) (0.13–0.012 Mya)

- Genus Eucyon

- E. adoxus

- E. davisi (5.3–3.6 Mya)

- E. intrepidus

- E. monticinensis

- E. odessanus

- E. skinneri (13.6–10.3 Mya)

- E. zhoui

- Genus Lycaon

- L. magnus

- L. sekowei

- Genus Mececyon

- Genus Megacyon

(3.6–2.6 Mya)

(3.6–2.6 Mya)

- M. merriami (3.6–2.6 Mya)

- Genus Nurocyon

- N. chonokhariensis

- Genus Xenocyon

[lower-alpha 5]

[lower-alpha 5]

- X. africanus

- X. antonii

- X. falconeri

- X. lycaonoides (0.78–0.3 Mya)

- Genus Aenocyon

- Subtribe Cerdocyonina

- Genus Cerdocyon

- C. ensenadensis[79]

- C. texanus (4.9–1.8 Mya)

- Genus Nyctereutes

- N. abdeslami (3.6–2.6 Mya)

- N. donnezani

- N. megamastoides (2.6–0.13 Mya)

- N. sinensis

- N. terblanchei

- N. tingi

- Genus Protocyon

- P. orcesi (0.78–0.012 Mya)

- P. scagliarum

- P. troglodytes (0.13–0.012 Mya)

- Genus Speothos

- S. pacivorus (Pleistocene bush dog)

- Genus Theriodictis

(1.8 Mya)

(1.8 Mya)

- T. floridanus (1.8 Mya)

- Genus Cerdocyon

- Subtribe Canina

- Tribe Vulpini

- Genus Ferrucyon

[80]

[80]

- F. avius (4.9–2.6 Mya)[80]

- Genus Metalopex

(10–4.9 Mya)

(10–4.9 Mya)

- M. bakeri (10–4.9 Mya)

- M. macconnelli (10–5.3 Mya)

- M. merriami (10–5.3 Mya)

- Genus Prototocyon

- P. curvipalatus

- P. recki

- Genus Vulpes

- V. alopecoides (2.5–0.13 Mya)

- V. angustidens

- V. beihaiensis

- V. chikushanensis

- V. galaticus

- V. praecorsac (3.2–0.78 Mya)

- V. praeglacialis

- V. riffautae

- V. skinneri

- V. stenognathus (14–0.3 Mya)

- V. qiuzhudingi[81]

- Genus Ferrucyon

- Urocyon

- Genus Urocyon

- U. minicephalus (1.8–0.3 Mya)

- U. progressus (4.9–1.8 Mya)

- Genus Urocyon

- Basal Caninae

- Genus Leptocyon

(31–10 Mya)

(31–10 Mya)

- L. delicatus (31–20 Mya)

- L. douglassi (31–26 Mya)

- L. gregorii (25–20 Mya)

- L. leidyi (20–14 Mya)

- L. matthewi (14–10 Mya)

- L. mollis (31–20 Mya)

- L. tejonensis (14–10 Mya)

- L. vafer (14–10 Mya)

- L. vulpinus (20–16 Mya)

- Genus Leptocyon

- Unclassified

- Genus Protemnocyon

(34–33 Mya)

(34–33 Mya)

- P. inflatus (34–33 Mya)

- Genus Protemnocyon

Subfamily Borophaginae

- Tribe Borophagini (26–1.8 Mya)

- Genus Cormocyon (26–20 Mya)

- C. copei (26–20 Mya)

- C. haydeni (25–20 Mya)

- Genus Desmocyon (20–16 Mya)

- D. matthewi (20–16 Mya)

- D. thomsoni (20–16 Mya)

- Genus Euoplocyon (20–14 Mya)

- E. brachygnathus (16–14 Mya)

- E. spissidens (20–16 Mya)

- Genus Metatomarctus (20–16 Mya)

- M. canavus (20–16 Mya)

- Genus Microtomarctus (16–14 Mya)

- M. conferta (16–14 Mya)

- Genus Protomarctus (16–14 Mya)

- P. optatus (16–14 Mya)

- Genus Psalidocyon (16–14 Mya)

- P. marianae (16–14 Mya)

- Genus Tephrocyon (16–14 Mya)

- T. rurestris (16–14 Mya)

- Subtribe Aelurodontina (16–5.3 Mya)

- Subtribe Borophagina (16–1.8 Mya)

- Genus Borophagus (14–1.8 Mya)

- B. diversidens (4.9–1.8 Mya)

- B. dudleyi (5.3–3.6 Mya)

- B. hilli (5.3–3.6 Mya)

- B. littoralis (14–10 Mya)

- B. orc (5.3–4.9 Mya)

- B. parvus (10–4.9 Mya)

- B. pugnator (10–5.3 Mya)

- B. secundus (10–4.9 Mya)

- Genus Carpocyon (16–5.3 Mya)

- C. compressus (16–14 Mya)

- C. limosus (10–5.3 Mya)

- C. robustus (14–10 Mya)

- C. webbi (14–5.3 Mya)

- Genus Epicyon (16–4.9 Mya)

- E. aelurodontoides (10–4.9 Mya)

- E. haydeni (10–4.9 Mya)

- E. saevus (16–4.9 Mya)

- Genus Paratomarctus (16–5.3 Mya)

- P. euthos (14–10 Mya)

- P. temerarius (16–5.3 Mya)

- Genus Protepicyon (16–14 Mya)

- P. raki (16–14 Mya)

- Genus Borophagus (14–1.8 Mya)

- Subtribe Cynarctina (16–10 Mya)

- Genus Cynarctus (16–10 Mya)

- C. crucidens (12–10 Mya)

- C. galushai (16–14 Mya)

- C. marylandica (16–14 Mya)

- C. saxatilis (16–14 Mya)

- C. voorhiesi (14–10 Mya)

- C. wangi (16–14 Mya)[83]

- Genus Paracynarctus (16–14 Mya)

- P. kelloggi (16–14 Mya)

- P. sinclairi (16–14 Mya)

- Genus Cynarctus (16–10 Mya)

- Genus Cormocyon (26–20 Mya)

- Tribe Phlaocyonini (30.8–13.6 Mya)

- Genus Cynarctoides (31–14 Mya)

- C. acridens (20–14 Mya)

- C. emryi (20–16 Mya)

- C. gawnae (20–16 Mya)

- C. harlowi (25–20 Mya)

- C. lemur (31–20 Mya)

- C. luskensis (25–20 Mya)

- C. roii (31–26 Mya)

- Genus Phlaocyon (31–16 Mya)

- P. achoros (25—20 Mya)

- P. annectens (25–20 Mya)

- P. latidens (31–20 Mya)

- P. leucosteus (20–16 Mya)

- P. mariae(20–16 Mya)

- P. marslandensis (20–16 Mya)

- P. minor (25–16 Mya)

- P. multicuspus (25–20 Mya)

- P. taylori (31–25 Mya)[84]

- P. yatkolai (20–16 Mya)

- Genus Cynarctoides (31–14 Mya)

- Basal Borophaginae

- Genus Archaeocyon (31–20 Mya)

- A. falkenbachi (31–20 Mya)

- A. leptodus (31–26 Mya)

- A. pavidus (31–26 Mya)

- Genus Otarocyon (34–26 Mya)

- O. cooki (31–26 Mya)

- O. macdonaldi (34–33 Mya)

- Genus Oxetocyon (33–31 Mya)

- O. cuspidatus (33–31 Mya)

- Genus Rhizocyon (31–20 Mya)

- R. oregonensis (31–20 Mya)

- Genus Archaeocyon (31–20 Mya)

Subfamily Hesperocyoninae

- Genus Cynodesmus (31–20 Mya)

- C. martini (31–20 Mya)

- C. thooides (31–26 Mya)

- Genus Caedocyon (31–20 Mya)

- C. tedfordi (31–20 Mya)

- Genus Ectopocynus (31–16 Mya)

- E. antiquus (31–20 Mya)

- E. intermedius (31–20 Mya)

- E. siplicidens (20–16 Mya)

- Genus Enhydrocyon (31–20 Mya)

- E. basilatus (25–20 Mya)

- E. crassidens (26–20 Mya)

- E. pahinsintewkpa (26–20 Mya)

- E. stenocephalus (31–20 Mya)

- Genus Hesperocyon (37–31 Mya)

- H. coloradensis (34–33 Mya)

- H. gregarius (37–31 Mya)

- Genus Mesocyon (33–20 Mya)

- M. brachyops (31–20 Mya)

- M. coryphaeus (31–20 Mya)

- M. temnodon (33–20 Mya)

- Genus Osbornodon (33–14 Mya)

- O. brachypus (20–16 Mya)

- O. fricki (16–14 Mya)

- O. iamonensis (20–16 Mya)

- O. renjiei (33–31 Mya)

- O. scitulus (21–16 Mya)[85]

- O. sesnoni (31–20 Mya)

- O. wangi (31–20 Mya)[84]

- Genus Paraenhydrocyon (25–20 Mya)

- P. josephi (25–20 Mya)

- P. robustus (25–20 Mya)

- P. wallovianus (25–20 Mya)

- Genus Philotrox (31–26 Mya)

- P. condoni (31–26 Mya)

- Genus Prohesperocyon (37–34 Mya)

- P. wilsoni (37–34 Mya)

- Genus Sunkahetanka (31–26 Mya)

- S. geringensis (31–26 Mya)

Notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Population figures rounded to the nearest hundred. Population trends as described by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ The Falklands Island wolf is believed to have been driven extinct in 1876[31]

- ↑ The South American fox is believed to have gone extinct sometime between 1454 and 1626[33]

- ↑ Also potentially placed in the Eucyon genus

- ↑ Xenocyon is sometimes considered a subgenus of Canis

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gompper, Matthew E. (October 17, 2013). "1.4 – The demographics and ownership of free-ranging dogs". Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-164011-7.

- ↑ Mivart, St. George Jackson (1890). Dogs, Jackals, Wolves, and Foxes: A Monograph of the Canidae. R. H. Porter. pp. xiv–xxxvi. https://archive.org/details/dogsjackalswolv00keulgoog. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ↑ Fahey, Bridget; Myers, Phil (2000). "Canidae: Coyotes, dogs, foxes, jackals, and wolves". University of Michigan. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Canidae/.

- ↑ Giemsch, Liane; Feine, Susanne C.; Alt, Kurt W.; Fu, Qiaomei; Knipper, Corina; Krause, Johannes; Lacy, Sarah; Nehlich, Olaf et al. (April 7–11, 2015). "Interdisciplinary investigations of the late glacial double burial from Bonn-Oberkassel". 57th Annual Meeting. Heidenheim an der Brenz, Germany: Hugo Obermaier Society for Quaternary Research and Archaeology of the Stone Age. pp. 36–37.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Wang, X. (1994). "Phylogenetic systematics of the Hesperocyoninae". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 221: 1–207.

- ↑ "Small-eared zorro (Atelocynus microtis)". ARKive. Wildscreen. http://www.arkive.org/small-eared-zorro/atelocynus-microtis/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Leite-Pitman, M. R. P.; Williams, R. S. R. (2011). "Atelocynus microtis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T6924A12814890. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T6924A12814890.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/6924/12814890.

- ↑ Canids: Species status and conservation (2004 ed.). International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2004. pp. 26–31.

- ↑ Viranta, S. et al. (December 2017). "Rediscovering a forgotten canid species". BMC Zoology 2 (6). doi:10.1186/s40850-017-0015-0. http://nrm.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1089580/FULLTEXT01. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Hoffmann, M.; Atickem, A. (2019). "Canis lupaster". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T118264888A118265889. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T118264888A118265889.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/118264888/118265889.

- ↑ Eddine, A.; Mostefai, N.; De Smet, K.; Klees, D.; Ansorge, H.; Karssene, Y.; Nowak, C.; Leer, P. (November 1, 2017). "Diet composition of a Newly Recognized Canid Species, the African Golden Wolf (Canis anthus), in Northern Algeria". Annales Zoologici Fennici 54 (5–6): 347–356. doi:10.5735/086.054.0506.

- ↑ Bekoff, M. (1977). "Canis latrans". Mammalian Species 79 (79): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3503817. ISSN 1545-1410. OCLC 46381503.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Kays, R. (2018). "Canis latrans". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T3745A103893556. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T3745A103893556.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/3745/103893556.

- ↑ Schneck, Marcus (February 2018). "Coyotes in Pennsylvania: What's the latest information and research?". The Patriot-News. https://www.pennlive.com/wildaboutpa/2018/02/coyotes_in_pennsylvania_whats.html.

- ↑ "Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis)". ARKive. Wildscreen. http://www.arkive.org/ethiopian-wolf/canis-simensis/.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Marino, J.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2011). "Canis simensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T3748A10051312. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T3748A10051312.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/3748/10051312.

- ↑ Sillero-Zubiri, C.; Gottelli, D. (December 2, 1994). "Canis simensis". Mammalian Species (385): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3504136. http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-485-01-0001.pdf. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Golden jackal (Canis aureus)". ARKive. Wildscreen. http://www.arkive.org/golden-jackal/canis-aureus/.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Hoffmann, M.; Arnold, J.; Duckworth, J. W.; Jhala, Y.; Kamler, J. F.; Krofel, M. (2018). "Canis aureus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T118264161A46194820. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T118264161A46194820.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/118264161/46194820.

- ↑ Heptner, V. G.; Naumov, N. P. (1998). Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol. II Part 1a, Sirenia and Carnivora (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears). Science Publishers. pp. 164–270. ISBN 978-1-886106-81-9. https://archive.org/stream/mammalsofsov211998gept#page/184/mode/2up. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Boitani, L.; Phillips, M.; Jhala, Y. (2018). "Canis lupus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T3746A119623865. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T3746A119623865.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/3746/119623865.

- ↑ "Grey wolf (Canis lupus)". ARKive. Wildscreen. http://www.arkive.org/grey-wolf/canis-lupus.

- ↑ Mech, L. David; Boitani, Luigi, eds (2003). Wolves: Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-226-51696-7.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Berta, A. (November 23, 1982). "Cerdocyon thous". Mammalian Species (186): 1–4. doi:10.2307/3503974.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Lucherini, M. (2015). "Cerdocyon thous". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T4248A81266293. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T4248A81266293.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/4248/81266293.

- ↑ "Maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus)". ARKive. Wildscreen. http://www.arkive.org/maned-wolf/chrysocyon-brachyurus/.

- ↑ Dietz, J. M. (1984). "Ecology and social organization of the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus)". Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology (392): 1–51. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.392.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Paula, R. C.; DeMatteo, K. (2015). "Chrysocyon brachyurus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T4819A82316878. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T4819A82316878.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/4819/82316878.

- ↑ "Dhole (Cuon alpinus)". ARKive. Wildscreen. http://www.arkive.org/dhole/cuon-alpinus/.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Kamler, J. F.; Songsasen, N.; Jenks, K.; Srivathsa, A.; Sheng, L.; Kunkel, K. (2015). "Cuon alpinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T5953A72477893. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T5953A72477893.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/5953/72477893.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2015). "Dusicyon australis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T6923A82310440. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T6923A82310440.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/6923/82310440.

- ↑ de Waal, H. O. (September 2017). "Demography and morphometry of black-backed jackals Canis mesomelasin South Africa and Namibia". African Large Predator Research Unit. https://www.ufs.ac.za/docs/librariesprovider22/animal-and-wildlife-and-grassland-sciences-documents/alpru-documents/all-documents/alpru/de-waal_2017_demography-and-morphometry-of-black-backed-jackals-canis-mesomelas-in-south-africa-and-namibia.pdf?sfvrsn=4b68a621_0. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Hoffmann, M. (2014). "Canis mesomelas". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T3755A46122476. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T3755A46122476.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/3755/46122476.

- ↑ Minnie, Liaan; Avenant, N.; Drouilly, Marine; Samuels, Mogamat (November 2018). "Biology and ecology of black-backed jackal and caracal". Livestock predation and its management in South Africa: a scientific assessment. Centre for African Conservation Ecology. pp. 178–204.

- ↑ "Side-striped jackal". Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife (2nd ed.). DK Adult. August 29, 2011. ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Hoffmann, M. (2014). "Canis adustus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T3753A46254734. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T3753A46254734.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/3753/46254734.

- ↑ Camacho, G.; Page-Nicholson, S.; Child, M. F.; Do Linh San, E. (2016). "7. A conservation assessment of Canis adustus". The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho. South African National Biodiversity Institute and Endangered Wildlife Trust. https://www.ewt.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/7.-Side-striped-Jackal-Canis-adustus_LC.pdf. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ↑ "Side-Striped Jackal". IUCN Canid Specialist Group. https://www.canids.org/species/view/PREKMO428071.

- ↑ "Culpeo". Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife (2nd ed.). DK Adult. August 29, 2011. ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Lucherini, M. (2016). "Lycalopex culpaeus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T6929A85324366. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T6929A85324366.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/6929/85324366.

- ↑ Novaro, Andres J.; Moraga, Claudio A.; Bricen, Cristobal; Funes, Martin C.; Marino, Andrea (2009). "First records of culpeo (Lycalopex culpaeus) attacks and cooperative defense by guanacos (Lama guanicoe)". Mammalian Species 73 (2). doi:10.1515/MAMM.2009.016.

- ↑ 44.00 44.01 44.02 44.03 44.04 44.05 44.06 44.07 44.08 44.09 44.10 44.11 44.12 44.13 44.14 44.15 44.16 44.17 44.18 44.19 44.20 44.21 44.22 44.23 44.24 44.25 44.26 Hunter, Luke (January 8, 2019). Carnivores of the World (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 110–126. ISBN 978-0-691-18295-7.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Silva-Rodríguez, E.; Farias, A.; Moreira-Arce, D.; Cabello, J.; Hidalgo-Hermoso, E.; Lucherini, M.; Jiménez, J. (2016). "Lycalopex fulvipes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41586A85370871. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41586A85370871.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/41586/85370871.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Dalponte, J.; Courtenay, O. (2008). "Lycalopex vetulus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T6926A12815527. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T6926A12815527.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/6926/12815527.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Lucherini, M. (2016). "Lycalopex gymnocercus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T6928A85371194. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T6928A85371194.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/6928/85371194.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Cossios, D. (2017). "Lycalopex sechurae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T6925A86074993. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T6925A86074993.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/6925/86074993.

- ↑ "Sechuran fox". IUCN Canid Specialist Group. https://www.canids.org/species/view/PREKIA411651.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Lucherini, M. (2016). "Lycalopex griseus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T6927A86440397. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T6927A86440397.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/6927/86440397.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Woodroffe, R.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2012). "Lycaon pictus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T12436A16711116. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012.RLTS.T12436A16711116.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/12436/16711116.

- ↑ "Bush dog (Speothos venaticus)". ARKive. Wildscreen. http://www.arkive.org/bush-dog/speothos-venaticus/.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 DeMatteo, K.; Michalski, F.; Leite-Pitman, M. R. P. (2011). "Speothos venaticus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T20468A9203243. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T20468A9203243.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/20468/9203243.

- ↑ Castelló, José R. (September 11, 2018). Canids of the World. Princeton University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-691-17685-7.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 55.4 Kauhala, K.; Saeki, M. (2016). "Nyctereutes procyonoides". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T14925A85658776. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T14925A85658776.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/14925/85658776.

- ↑ Hsieh-Yi; Yi-Chiao; Fu, Yu; Rissi, Mark; Maas, Barbera (August 22, 2019). Fun Fur? A report on the Chinese fur industry. Care for the Wild International. http://www.careforthewild.com/files/Furreport05.pdf.

- ↑ Kim, Sang-In; Oshida, Tatsuo; Lee, Hang; Min, Mi-Sook; Kimura, Junpei (2015). "Evolutionary and biogeographical implications of variation in skull morphology of raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides, Mammalia: Carnivora)" (in en). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 116 (4): 856–872. doi:10.1111/bij.12629. ISSN 1095-8312. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bij.12629.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 Hoffmann, M. (2014). "Otocyon megalotis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T15642A46123809. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T15642A46123809.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/15642/46123809.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Angerbjörn, A.; Tannerfeldt, M. (2014). "Vulpes lagopus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T899A57549321. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-2.RLTS.T899A57549321.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/899/57549321.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Jhala, Y. (2016). "Vulpes bengalensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T23049A81069636. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T23049A81069636.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/23049/81069636.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Hoffmann, M.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2015). "Vulpes cana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T23050A48075169. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T23050A48075169.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/23050/48075169.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Hoffmann, M. (2014). "Vulpes chama". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T23060A46126992. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T23060A46126992.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/23060/46126992.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Murdoch, J. D. (2014). "Vulpes corsac". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T23051A59049446. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-2.RLTS.T23051A59049446.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/23051/59049446.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Wacher, T.; Bauman, K.; Cuzin, F. (2015). "Vulpes zerda". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T41588A46173447. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T41588A46173447.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/41588/46173447.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 Cypher, B.; List, R. (2014). "Vulpes macrotis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T41587A62259374. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T41587A62259374.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/41587/62259374.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 Sillero-Zubiri, C.; Wacher, T. (2012). "Vulpes pallida". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T23052A16813736. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012.RLTS.T23052A16813736.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/23052/16813736.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Mallon, D.; Murdoch, J. D.; Wacher, T. (2015). "Vulpes rueppellii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T23053A46197483. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T23053A46197483.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/23053/46197483.

- ↑ "Red fox (Vulpes vulpes)". ARKive. Wildscreen. http://www.arkive.org/red-fox/vulpes-vulpes/.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Hoffmann, M.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2016). "Vulpes vulpes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T23062A46190249. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T23062A46190249.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/23062/46190249.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Moehrenschlager, A.; Sovada, M. (2016). "Vulpes velox". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T23059A57629306. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T23059A57629306.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/23059/57629306.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Harris, R. (2014). "Vulpes ferrilata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T23061A46179412. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T23061A46179412.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/23061/46179412.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Roemer, G.; Cypher, B.; List, R. (2016). "Urocyon cinereoargenteus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22780A46178068. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T22780A46178068.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22780/46178068.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Coonan, T.; Ralls, K.; Hudgens, B.; Cypher, B.; Boser, C. (2013). "Urocyon littoralis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T22781A13985603. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T22781A13985603.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22781/13985603.

- ↑ Wang, X.; Tedford, R. H.; Taylor, B. E. (1999). "Phylogenetic systematics of the Borophaginae". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 243: 1–391.

- ↑ Tedford, R. H.; Wang, X.; Taylor, B. E. (2009). "Phylogenetic systematics of the North American fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae)". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 325: 1–218. doi:10.1206/574.1. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/bitstream/2246/5999/1/B325.pdf.

- ↑ Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H. (April 26, 2010). Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. Columbia University Press. pp. 169–175. ISBN 978-0-231-13529-0.

- ↑ Brugal, J.; Boudadi-Maligne, M. (2011). "Quaternary small to large canids in Europe: Taxonomic status and biochronological contribution". Quaternary International 243 (1): 171–182. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.01.046. Bibcode: 2011QuInt.243..171B.

- ↑ Amri, L.; Bartolini Lucenti, S.; Mtimet, M. S.; Karoui-Yaakoub, N.; Ros-Montoya, S.; Espigares, M.; Boughdiri, M.; Bel Haj Ali, N. et al. (2017). "Canis othmanii sp. nov. (Carnivora, Canidae) from the early Middle Pleistocene site of Wadi Sarrat (Tunisia)". Comptes Rendus Palevol 16 (7): 774–782. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2017.05.004.

- ↑ Ramirez, M. A.; Prevosti, F. J. (2014). "Systematic Revision of "Canis" ensenadensis Ameghino, 1888 (Carnivora, Canidae) and the Description of a New Specimen from the Pleistocene of Argentina". Ameghiniana 51: 37. doi:10.5710/AMEGH.23.12.2013.1163.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 R., Damián; Prevosti, F. J.; Lucenti, S. B.; Montellano-Ballesteros, M.; Carreño, A. L. (2020). "The Pliocene canid Cerdocyon avius was not the type of fox that we thought". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 40 (2): e1774889. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1774889.

- ↑ Wang, Xiaoming; Tseng, Zhijie Jack; Li, Qiang; Takeuchi, Gary T.; Xie, Guangpu (11 June 2014). "From 'third pole' to north pole: a Himalayan origin for the arctic fox". Proceedings of the Royal Society B (Royal Society) 281 (1787): 20140893. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0893. PMID 24920475.

- ↑ Wang, X.; Wideman, B. C.; Nichols, R.; Hanneman, D. L. (2004). "A new species of Aelurodon (Carnivora, Canidae) from the Barstovian of Montana". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24 (2): 445–452. doi:10.1671/2493. http://www.nhm.org/expeditions/rrc/wang/documents/Wangetal2004MontanaAelurodon.pdf. Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ↑ Jasinski, S. E.; Wallace, S. C. (2016). "A Borophagine canid (Carnivora: Canidae: Borophaginae) from the middle Miocene Chesapeake Group of eastern North America". Journal of Paleontology 89 (6): 1082–1088. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.17.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Hayes, F. G. (2000). "The Brooksville 2 local fauna (Arikareean, latest Oligocene) Hernando County, Florida". Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 43 (1): 1–47.

- ↑ Wang, X. (2003). "New Material of Osbornodon from the Early Hemingfordian of Nebraska and Florida". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 279: 163–176. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2003)279<0163:C>2.0.CO;2. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace/bitstream/2246/447/19/B279a08.pdf. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

Template:Featured list is only for Wikipedia:Featured lists.