Chemistry:Conjugated linoleic acid

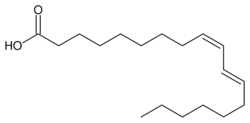

Conjugated linoleic acids (CLA) are a family of isomers of linoleic acid. In principle, 28 isomers are possible. CLA is found mostly in the meat and dairy products derived from ruminants. The two C=C double bonds are conjugated (i.e., separated by a single bond). CLAs can be either cis-fats or trans-fats.

CLA is marketed as a dietary supplement on the basis of its supposed health benefits.[1]

Biochemistry

CLA describes a variety of isomers of octadecadienoic fatty acids.[2]

Commonly, CLAs are studied as some mixture of isomers wherein the isomers c9,t11-CLA (rumenic acid) and t10,c12-CLA were the most abundant.[3] Studies show however that individual isomers have distinct health effects.[4][5]

Conjugated linoleic acid is both a trans fatty acid and a cis fatty acid. The cis bond causes a lower melting point and, ostensibly, also the observed beneficial health effects. Unlike other trans fatty acids, it may have beneficial effects on human health.[6] CLA is conjugated, and in the United States, trans linkages in a conjugated system are not counted as trans fats for the purposes of nutritional regulations and labeling.[citation needed] CLA and some trans isomers of oleic acid are produced by microorganisms in the rumens of ruminants. Non-ruminants, including humans, produce certain isomers of CLA from trans isomers of oleic acid, such as vaccenic acid, which is converted to CLA by delta-9-desaturase.[7][8]

In healthy humans, CLA and the related conjugated linolenic acid (CLNA) isomers are bioconverted from linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid, respectively, mainly by Bifidobacterium bacteria strains inhabiting the gastrointestinal tract.[citation needed] However, this bioconversion may not occur at any significant level in those with a digestive disease, gluten sensitivity, or dysbiosis.[9][10][11][12]

Health effects

CLA is marketed in dietary supplement form for its supposed anti-cancer benefit (for which there is no strong evidence or known mechanism, and very few studies conducted so far)[13] and as a bodybuilding aid.[1] A 2004 review of the evidence said that while CLA seemed to benefit animals, there was a lack of good evidence of human health benefits despite the many claims made for it.[14]

Likewise, there is insufficient evidence that CLA has a useful benefit for overweight or obese people as it has no long-term effect on body composition.[15] Although CLA has shown an effect on insulin response in diabetic rats, there is no evidence of this effect in humans.[16]

Dietary sources

Food products from grass-fed ruminants (e.g. mutton and beef) are good sources of CLA and contain much more of it than those from grain-fed animals.[17] Eggs from chickens that have been fed CLA are also rich in CLA, and CLA in egg yolks has been shown to survive the temperatures encountered during frying.[18] Some mushrooms, such as Agaricus bisporus and Agaricus subrufescens, are rare non-animal sources of CLA.[19][20]

However, dietary punicic acid—which is abundant in pomegranate seeds—is converted to the CLA rumenic acid upon absorption in rats,[21] suggesting that non-animal sources can still effectively provide dietary CLA.

History

In 1979 CLAs were found to inhibit chemically-induced cancer in mice [22] and research on its biological activity has continued.[23]

In 2008, the United States Food and Drug Administration categorized CLA as generally recognized as safe (GRAS).[24]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Health Professional's Guide to Dietary Supplements. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-0-7817-4672-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=hV2_TdmoDo8C&pg=PA14.

- ↑ Weiss, M.F.; Martz, F.A.; Lorenzen, C.L. (2004-04-01). "REVIEWS: Conjugated Linoleic Acid: Historical Context and Implications" (in en). The Professional Animal Scientist 20 (2): 127–135. doi:10.15232/S1080-7446(15)31287-0. ISSN 1080-7446. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1080744615312870.

- ↑ "Fatty Acid Profiles of Liver, Adipose Tissue, Speen, and Heart of Mice Fed Diets Containing T10, C-12-, and C9, T11-Conjugated Linoleic Adic". http://www.ars.usda.gov/research/publications/publications.htm?seq_no_115=179685.

- ↑ Tricon S; Burdge GC; Kew S et al. (September 2004). "Opposing effects of cis-9,trans-11 and trans-10,cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid on blood lipids in most healthy humans". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80 (3): 614–20. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.3.614. PMID 15321800.

- ↑ Ulf Risérus, MMed; Samar Basu; Stefan Jovinge, MD; Gunilla Nordin Fredrikson; Johan Ärnlöv, MD; Bengt Vessby, MD (September 2002). "Supplementation With Conjugated Linoleic Acid Causes Isomer-Dependent Oxidative Stress and Elevated C-Reactive Protein". Circulation 106 (15): 1925–9. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000033589.15413.48. 01.CIR.0000033589.15413.48v1. PMID 12370214. http://intl-circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/short/106/15/1925. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ↑ "II International Congress on CLA from Experimental Models to Human Application". http://www.milk.co.uk/page.aspx?intPageID=283.

- ↑ "Trans-11-18 : 1 is effectively Delta9-desaturated compared with trans-12-18 : 1 in humans". Br J Nutr 95 (4): 752–761. April 2006. doi:10.1079/BJN20051680. PMID 16571155.

- ↑ "Vaccenic acid feeding increases tissue levels of conjugated linoleic acid and suppresses development of premalignant lesions in rat mammary gland". Nutr Cancer 41 (1–2): 91–7. 2001. doi:10.1080/01635581.2001.9680617. PMID 12094634.

- ↑ Estelle Devillard; Freda M. McIntosh; Sylvia H. Duncan; R. John Wallace (March 2007). "Metabolism of Linoleic Acid by Human Gut Bacteria: Different Routes for Biosynthesis of Conjugated Linoleic Acid". Journal of Bacteriology 189 (6): 2566–2570. doi:10.1128/JB.01359-06. PMID 17209019.

- ↑ E. Barrett; R. P. Ross; G. F. Fitzgerald; and C. Stanton (April 2007). "Rapid Screening Method for Analyzing the Conjugated Linoleic Acid Production Capabilities of Bacterial Cultures". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 73 (7): 2333–2337. doi:10.1128/AEM.01855-06. PMID 17277221. Bibcode: 2007ApEnM..73.2333B.

- ↑ "Conjugated linoleic and linolenic acid production kinetics by bifidobacteria differ among strains". International Journal of Food Microbiology 155 (3): 234–240. April 2012. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.02.012. PMID 22405353.

- ↑ Esther Jiméneza; M. Antonia Villar-Tajadurab; María Marína; Javier Fontechab; Teresa Requenac; Rebeca Arroyoa; Leónides Fernándeza; Juan M. Rodrígueza (July 2012). "Complete Genome Sequence of Bifidobacterium breve CECT 7263, a Strain Isolated from Human Milk". Journal of Bacteriology 194 (14): 3762–3763. doi:10.1128/JB.00691-12. PMID 22740680. PMC 3393482. https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/101263/1/Complete%20Genome%20Sequence.pdf.

- ↑ "Conjugated linoleic acids (CLAs) decrease prostate cancer cell proliferation: different molecular mechanisms for cis-9, trans-11 and trans-10, cis-12 isomers". Carcinogenesis 25 (7): 1185–91. 2004. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgh116. PMID 14976130.

- ↑ "Conjugated linoleic acid: health implications and effects on body composition". J Am Diet Assoc 104 (6): 963–. June 2004. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2004.03.016. PMID 15175596.

- ↑ "The efficacy of long-term conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) supplementation on body composition in overweight and obese individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". Eur J Nutr 51 (2): 127–34. March 2012. doi:10.1007/s00394-011-0253-9. PMID 21990002.

- ↑ "Nutraceuticals in diabetes and metabolic syndrome". Cardiovascular Therapeutics 28 (4): 216–26. August 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00179.x. PMID 20633024.

- ↑ T. R. Dhiman; L. D. Satter; M. W. Pariza; M. P. Galli; K. Albright; M. X. Tolosa (1 May 2000). "Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA) Content of Milk from Cows Offered Diets Rich in Linoleic and Linolenic Acid". Journal of Dairy Science 83 (5): 1016–1027. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74966-6. PMID 10821577. https://www.journalofdairyscience.org/article/S0022-0302(00)74966-6/abstract. Retrieved 2006-05-27.

- ↑ Lin Yang; Ying Cao; Zhen-Yu Chen (2004). "Stability of conjugated linoleic acid isomers in egg yolk lipids during frying". Food Chemistry (Elsevier) 86 (4): 531–535. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.09.006.

- ↑ Chen, S.; Oh, SR; Phung, S; Hur, G; Ye, JJ; Kwok, SL; Shrode, GE; Belury, M et al. (2006). "Anti-aromatase activity of phytochemicals in white button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus)". Cancer Res. 66 (24): 12026–12034. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2206. PMID 17178902.

- ↑ W. J. Jang S. W. Hyung. Production of natural c9,t11 conjugated linoleic acid (c9,t11 CLA) by submerged liquid culture of mushrooms. Division of Applied Life Science (BK21), Graduate School, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, 660-701, South Korea.. http://ift.confex.com/ift/2004/techprogram/paper_24802.htm.

- ↑ "Conjugated linolenic acid is slowly absorbed in rat intestine, but quickly converted to conjugated linoleic acid". J Nutr 136 (8): 2153–9. 1 August 2006. doi:10.1093/jn/136.8.2153. PMID 16857834. http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/content/abstract/136/8/2153. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ "Anticarcinogens from fried ground beef: heat-altered derivatives of linoleic acid". Carcinogenesis 8 (12): 1881–7. 1987. doi:10.1093/carcin/8.12.1881. PMID 3119246.

- ↑ Pariza MW (June 2004). "Perspective on the safety and effectiveness of conjugated linoleic acid". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79 (6 Suppl): 1132S–1136S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/79.6.1132S. PMID 15159246.

- ↑ "CLA approved as food ingredient". University of Wisconsin Madison. July 25, 2008. http://www.news.wisc.edu/15415. "On July 24, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced its finding that conjugated linoleic acid, known as CLA, is "generally regarded as safe" for use in foods"

|