Chemistry:Dry cell

thumb|upright|Line art drawing of a dry cell: 1. brass cap, 2. plastic seal, 3. expansion space, 4. porous cardboard, 5. zinc can, 6. carbon rod, 7. chemical mixture

A dry cell is a type of electric battery, commonly used for portable electrical devices. Unlike wet cell batteries, which have a liquid electrolyte, dry cells use an electrolyte in the form of a paste, and are thus less susceptible to leakage.

The dry cell was developed in 1886 by the German scientist Carl Gassner, after development of wet zinc–carbon batteries by Georges Leclanché in 1866. A type of dry cell was also developed by the Japanese inventor Sakizō Yai in 1887.

History

thumb|left|upright|Dry cell battery by Wilhelm Hellesen 1890

Many experimenters tried to immobilize the electrolyte of an electrochemical cell to make it more convenient to use. The Zamboni pile of 1812 is a high-voltage dry battery but capable of delivering only minute currents. Various experiments were made with cellulose, sawdust, spun glass, asbestos fibers, and gelatine.[1]

In 1886, Carl Gassner obtained a German patent (No. 37,758) on a variant of the (wet) Leclanché cell, which came to be known as the dry cell because it did not have a free liquid electrolyte. Instead, the ammonium chloride was mixed with Plaster of Paris to create a paste, with a small amount of zinc chloride added in to extend the shelf life. The manganese dioxide cathode was dipped in this paste, and both were sealed in a zinc shell, which also acts as the anode. In November 1887, he obtained U.S. Patent 373,064 for the same device.[2] A dry-battery was invented in Japan during the Meiji Era in 1887. The inventor was Sakizō Yai.[3] However, Yai didn't have enough money to file the patent,[4] the first patent holder of a battery in Japan was not Yai, but Takahashi Ichisaburo. Wilhelm Hellesen also invented a dry-battery in 1887 and obtained U.S. Patent 439,151 in 1890.[5]

Unlike previous wet cells, Gassner's dry cell is more solid, does not require maintenance, does not spill, and can be used in any orientation. It provides a potential of 1.5 volts. The first mass-produced model was the Columbia dry cell, first marketed by the National Carbon Company in 1896.[6] The NCC improved Gassner's model by replacing the plaster of Paris with coiled cardboard, an innovation that leaves more space for the cathode and makes the battery easier to assemble. It was the first convenient battery for the masses and made portable electrical devices practical.

The zinc–carbon cell (as it came to be known) is still manufactured today.

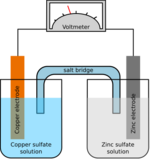

Design

A dry cell uses a paste electrolyte, with only enough moisture to allow current to flow. Unlike a wet cell, a dry cell can operate in any orientation without spilling, as it contains no free liquid, making it suitable for portable equipment. By comparison, the first wet cells were typically fragile glass containers with lead rods hanging from the open top and needed careful handling to avoid spillage. Lead–acid batteries did not achieve the safety and portability of the dry cell until the development of the gel battery. Wet cells have continued to be used for high-drain applications, such as starting internal combustion engines, because inhibiting the electrolyte flow tends to reduce the current capability.

A common dry cell is the zinc–carbon cell, sometimes called the dry Leclanché cell, with a nominal voltage of 1.5 volts, the same as the alkaline cell (since both use the same zinc–manganese dioxide combination).

A standard dry cell comprises a zinc anode, usually in the form of a cylindrical pot, with a carbon cathode in the form of a central rod. The electrolyte is ammonium chloride in the form of a paste next to the zinc anode. The remaining space between the electrolyte and carbon cathode is taken up by a second paste consisting of ammonium chloride and manganese dioxide, the latter acting as a depolariser. In some designs, often marketed as "heavy duty", the ammonium chloride is replaced with zinc chloride.

Types

Primary cells are not rechargeable and are generally disposed of after the cell's internal reaction has consumed the reactive starting chemicals.

Secondary cells are rechargeable, and may be reused multiple times.

- Primary cell

- Zinc–carbon cell

- Alkaline cell

- Lithium cell

- Mercury cell

- Silver-oxide cell

- Secondary cell

See also

References

- ↑ W. E. Ayrton Practical Electricity; A Laboratory and Lecture Course for First Year ... 1897, reprint Read Books, 2008 ISBN 1-4086-9150-7, page 458

- ↑ "Galvanic Battery - Carl Gassner - U.S. Patent 373,064". http://todayinsci.com/G/Gassner_Carl/GassnerPatent373064.htm.

- ↑ "The history of the battery : 1) The Yai dry-battery". http://www.baj.or.jp/e/knowledge/history01.html.

- ↑ "三菱電機FA 第1回 先人に学ぶ 屋井先蔵 電気の時代を先取りし「乾電池王」と呼ばれた発明家 文化・教養 FA 羅針盤" (in ja). https://www.mitsubishielectric.co.jp/fa/compass/lectures/pioneers07/report.html.

- ↑ "The history of the battery". Battery Association of Japan. http://www.baj.or.jp/e/knowledge/history01.html.

- ↑ "The Columbia Dry Cell Battery". National Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/drycellbattery.html.