Chemistry:Zinc chloride

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Zinc chloride

| |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2331 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| ZnCl 2 | |

| Molar mass | 136.315 g/mol |

| Appearance | White hygroscopic and very deliquescent crystalline solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 2.907 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 290 °C (554 °F; 563 K)[1] |

| Boiling point | 732 °C (1,350 °F; 1,005 K)[1] |

| 432.0 g/(100 g) (25 °C) | |

| Solubility | soluble in ethanol, glycerol and acetone |

| Solubility in ethanol | 430.0 g/(100 ml) |

| −65.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure | |

| Tetrahedral, linear in the gas phase | |

| Pharmacology | |

| 1=ATC code }} | B05XA12 (WHO) |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Moderately toxic, irritant[2] |

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

| H302, H314, H410 | |

| P273, P280, P301+330+331, P305+351+338, P308+310Script error: No such module "Preview warning".Category:GHS errors | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

|

LC50 (median concentration)

|

1260 mg/m3 (rat, 30 min) 1180 mg-min/m3[4] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 1 mg/m3 (fume)[3] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 1 mg/m3 ST 2 mg/m3 (fume)[3] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

50 mg/m3 (fume)[3] |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

|

Other cations

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Zinc chloride is the name of inorganic chemical compounds with the formula ZnCl

2. It forms hydrates. Zinc chloride, anhydrous and its hydrates are colorless or white crystalline solids, and are highly soluble in water. Five hydrates of zinc chloride are known, as well as four forms of anhydrous zinc chloride.[5] This salt is hygroscopic and even deliquescent. Zinc chloride finds wide application in textile processing, metallurgical fluxes, and chemical synthesis. No mineral with this chemical composition is known aside from the very rare mineral simonkolleite, Zn

5(OH)

8Cl

2 · H2O.

Structure and properties

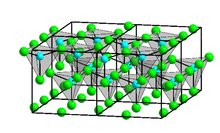

Four crystalline forms (polymorphs) of ZnCl

2 are known: α, β, γ, and δ. Each case features tetrahedral Zn2+ centers.[6]

| Form | Crystal system | Pearson symbol | Space group | No. | a (nm) | b (nm) | c (nm) | Z | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | tetragonal | tI12 | I42d | 122 | 0.5398 | 0.5398 | 0.64223 | 4 | 3.00 |

| β | tetragonal | tP6 | P42/nmc | 137 | 0.3696 | 0.3696 | 1.071 | 2 | 3.09 |

| γ | monoclinic | mP36 | P21/c | 14 | 0.654 | 1.131 | 1.23328 | 12 | 2.98 |

| δ | orthorhombic | oP12 | Pna21 | 33 | 0.6125 | 0.6443 | 0.7693 | 4 | 2.98 |

Here a, b, and c are lattice constants, Z is the number of structure units per unit cell, and ρ is the density calculated from the structure parameters.[7][8][9]

The orthorhombic form (δ) rapidly changes to one of the other forms on exposure to the atmosphere. A possible explanation is that the OH−

ions originating from the absorbed water facilitate the rearrangement.[6] Rapid cooling of molten ZnCl

2 gives a glass.[10]

Molten ZnCl

2 has a high viscosity at its melting point and a comparatively low electrical conductivity, which increases markedly with temperature.[11][12] As indicated by a Raman scattering study, the viscosity is explained by the presence of polymers,[13]. Neutron scattering study indicated the presence of tetrahedral ZnCl

4 centers, which requires aggregation of ZnCl

2 monomers as well..[14]

In the gas phase, ZnCl

2 molecules are linear with a bond length of 205 pm.

Hydrates

Five hydrates of zinc chloride are known: ZnCl

2(H

2O)

n with n = 1, 1.5, 2.5, 3 and 4.[15] The tetrahydrate ZnCl

2(H

2O)

4 crystallizes from aqueous solutions of zinc chloride.[15]

Preparation and purification

Anhydrous ZnCl

2 can be prepared from zinc and hydrogen chloride:

- Zn + 2 HCl → ZnCl

2 + H

2

Hydrated forms and aqueous solutions may be readily prepared similarly by treating Zn metal, zinc carbonate, zinc oxide, and zinc sulfide with hydrochloric acid:

- ZnS + 2 HCl + 4 H

2O → ZnCl

2(H

2O)

4 + H

2S

Unlike many other elements, zinc essentially exists in only one oxidation state, 2+, which simplifies the purification of the chloride.

Commercial samples of zinc chloride typically contain water and products from hydrolysis as impurities. Such samples may be purified by recrystallization from hot dioxane. Anhydrous samples can be purified by sublimation in a stream of hydrogen chloride gas, followed by heating the sublimate to 400 °C in a stream of dry nitrogen gas.[16] Finally, the simplest method relies on treating the zinc chloride with thionyl chloride.[17]

Reactions

The Zn2+

2 ion

Molten anhydrous ZnCl

2 at 500–700 °C dissolves zinc metal, and, on rapid cooling of the melt, a yellow diamagnetic glass is formed, which Raman studies indicate contains the Zn2+

2 ion.[15]

Salts of [ZnCl

4]2− and [Zn

2Cl

6]2− ions

A number of salts containing the tetrachlorozincate anion, [ZnCl

4]2−, are known.[11] "Caulton's reagent", V

2Cl

3(thf)

6] [Zn

2Cl

6], which is used in organic chemistry, is an example of a salt containing [Zn

2Cl

6]2−.[18][19] The compound Cs

3ZnCl

5 contains tetrahedral [ZnCl

4]2− and Cl−

anions,[6] so, the compound is not caesium pentachlorozincate, but caesium tetrachlorozincate chloride. No compounds containing the [ZnCl

6]4− ion (hexachlorozincate ion) have been characterized.[6]

Aqueous solutions of zinc chloride

Zinc chloride dissolves readily in water to give ZnCl

x(H

2O)

4-x species and some free chloride.[20][21][22] Aqueous solutions of ZnCl

2 are acidic: a 6 M aqueous solution has a pH of 1.[15] The acidity of aqueous ZnCl

2 solutions relative to solutions of other Zn2+ salts (say the sulfate) is due to the formation of the tetrahedral chloro aqua complexes where the reduction in coordination number from 6 to 4 further reduces the strength of the O–H bonds in the solvated water molecules.[23]

Alkaline solutions of zinc chloride

In alkali solution, zinc chloride converts to various zinc hydroxychlorides. These include [Zn(OH)

3Cl]2−, [Zn(OH)

2Cl

2]2−, [Zn(OH)Cl

3]2−, and the insoluble Zn

5(OH)

8Cl

2 · H2O. The latter is the mineral simonkolleite.[24] When zinc chloride hydrates are heated, HCl gas evolves and hydroxychlorides result.[25]

Solutions of zinc chloride in ammonia

When solutions of zinc chloride are treated with ammonia, various ammine complexes are produced. These include Zn(NH

3)

4Cl

2 · H2O and on concentration ZnCl

2(NH

3)

2.[26] The former contains the [Zn(NH

3)

6]2+ ion,[6] and the latter is molecular with a distorted tetrahedral geometry.[27] The species in aqueous solution have been investigated and show that [Zn(NH

3)

4]2+ is the main species present with [Zn(NH

3)

3Cl]+

also present at lower NH

3:Zn ratio.[28]

Zinc oxychloride cement

Aqueous zinc chloride reacts with zinc oxide to form an amorphous cement that was first investigated in 1855 by Stanislas Sorel. Sorel later went on to investigate the related magnesium oxychloride cement, which bears his name.[29]

Zinc hydroxide chloride

When hydrated zinc chloride is heated, one obtains a residue of Zn(OH)Cl e.g.[30]

- ZnCl

2 · 2H2O → Zn(OH)Cl + HCl + H

2O

Acidified zinc chloride

The compound ZnCl

2 · 0.5HCl · H2O may be prepared by careful precipitation from a solution of ZnCl

2 acidified with HCl. It contains a polymeric anion (Zn

2Cl−

5)

n with balancing monohydrated hydronium ions, H

5O+

2 ions.[6][31]

Cellulose dissolution in aqueous solutions of ZnCl

2

Cellulose dissolves in aqueous solutions of ZnCl

2, and zinc-cellulose complexes have been detected.[32] Cellulose also dissolves in molten ZnCl

2 hydrate and carboxylation and acetylation performed on the cellulose polymer.[33]

Using zinc chloride for preparing other zinc salts

Thus, although many zinc salts have different formulas and different crystal structures, these salts behave very similarly in aqueous solution. For example, solutions prepared from any of the polymorphs of ZnCl

2, as well as other halides (bromide, iodide), and the sulfate can often be used interchangeably for the preparation of other zinc compounds. Illustrative is the preparation of zinc carbonate:

Role in organic chemistry

Zinc chloride is used as a catalyst or reagent in diverse reactions conducted on an industrial scale. The partial hydrolysis of benzal chloride in the presence of zinc chloride is the main route to benzoyl chloride. It serves as a catalyst for the production of methylene-bis(dithiocarbamate).[5]

The combination of hydrochloric acid and ZnCl

2, known as the "Lucas reagent", is effective for the preparation of alkyl chlorides from alcohols. Similar reactions are the basis of industrial routes from methanol and ethanol respectively to methyl chloride and ethyl chloride.

Laboratory syntheses

Zinc chloride is a common reagent in the laboratory useful Lewis acid in organic chemistry.[34]

Molten zinc chloride catalyses the conversion of methanol to hexamethylbenzene:[35]

- 15 CH

3OH → C

6(CH

3)

6 + 3 CH

4 + 15 H

2O

Other examples include catalyzing (A) the Fischer indole synthesis,[36] and also (B) Friedel-Crafts acylation reactions involving activated aromatic rings[37][38]

Related to the latter is the classical preparation of the dye fluorescein from phthalic anhydride and resorcinol, which involves a Friedel-Crafts acylation.[39] This transformation has in fact been accomplished using even the hydrated ZnCl

2 sample shown in the picture above.

- Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

Zinc chloride also activates benzylic and allylic halides towards substitution by weak nucleophiles such as alkenes:[40]

In similar fashion, ZnCl

2 promotes selective Na[BH

3(CN)] reduction of tertiary, allylic or benzylic halides to the corresponding hydrocarbons.

Zinc chloride is also a useful starting reagent for the synthesis of many organozinc reagents, such as those used in the palladium catalyzed Negishi coupling with aryl halides or vinyl halides.[41] In such cases the organozinc compound is usually prepared by transmetallation from an organolithium or a Grignard reagent, for example:

Zinc enolates, prepared from alkali metal enolates and ZnCl

2, provide control of stereochemistry in aldol condensation reactions due to chelation on to the zinc. In the example shown below, the threo product was favored over the erythro by a factor of 5:1 when ZnCl

2 in DME/ether was used.[42] The chelate is more stable when the bulky phenyl group is pseudo-equatorial rather than pseudo-axial, i.e., threo rather than erythro.

Other uses

As a metallurgical flux

The use of zinc chloride as a flux, sometimes in a mixture with ammonium chloride (see also Zinc ammonium chloride), involves the production of HCl and its subsequent reaction with surface oxides.

Zinc chloride reacts with metal oxides (MO) to give derivatives of the idealized formula MZnOCl

2.[43][additional citation(s) needed] This reaction is relevant to the utility of ZnCl

2 solution as a flux for soldering — it dissolves passivating oxides, exposing the clean metal surface.[43] Fluxes with ZnCl

2 as an active ingredient are sometimes called "tinner's fluid".

Zinc chloride forms two salts with ammonium chloride: [NH

4]

2[ZnCl

4] and [NH

4]

3[ZnCl

4]Cl, which decompose on heating liberating HCl, just as zinc chloride hydrate does. The action of zinc chloride/ammonium chloride fluxes, for example, in the hot-dip galvanizing process produces H

2 gas and ammonia fumes.[44]

In textile and paper processing

Concentrated aqueous solutions of zinc chloride (more than 64% weight/weight zinc chloride in water) are capable of dissolving starch, silk, and cellulose.

Relevant to its affinity for these materials, ZnCl

2 is used as a fireproofing agent and in fabric "refresheners" such as Febreze. Vulcanized fibre is made by soaking paper in concentrated zinc chloride.

Smoke grenades

The zinc chloride smoke mixture ("HC") used in smoke grenades contains zinc oxide, hexachloroethane and granular aluminium powder, which, when ignited, react to form zinc chloride, carbon and aluminium oxide smoke, an effective smoke screen.[45]

Fingerprint detection

Ninhydrin reacts with amino acids and amines to form a colored compound "Ruhemann's purple" (RP). Spraying with a zinc chloride solution forms a 1:1 complex RP:ZnCl(H

2O)

2, which is more readily detected as it fluoresces more intensely than RP.[46]

Disinfectant and wood preservative

Dilute aqueous zinc chloride was used as a disinfectant under the name "Burnett's Disinfecting Fluid". [47] From 1839 Sir William Burnett promoted its use as a disinfectant as well as a wood preservative.[48] The Royal Navy conducted trials into its use as a disinfectant in the late 1840s, including during the cholera epidemic of 1849; and at the same time experiments were conducted into its preservative properties as applicable to the shipbuilding and railway industries. Burnett had some commercial success with his eponymous fluid. Following his death however, its use was largely superseded by that of carbolic acid and other proprietary products.

Safety

Zinc chloride is a chemical irritant of the eyes, skin, and respiratory system.[5][49]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 O'Neil, M. J. (2001). The Merck index : an encyclopedia of chemicals, drugs, and biologicals. N. J.: Whitehouse Station. ISBN 978-0911910131. https://archive.org/details/merckindexency00onei.

- ↑ Zinc chloride toxicity

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0674". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0674.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Zinc chloride fume". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/idlh/7646857.html.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Dieter M. M. Rohe; Hans Uwe Wolf (2007). "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1002/14356007.a28_537.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Wells, A. F. (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-855370-0.

- ↑ Oswald, H. R.; Jaggi, H. (1960). "Zur Struktur der wasserfreien Zinkhalogenide I. Die wasserfreien Zinkchloride". Helvetica Chimica Acta 43 (1): 72–77. doi:10.1002/hlca.19600430109.

- ↑ Brynestad, J.; Yakel, H. L. (1978). "Preparation and Structure of Anhydrous Zinc Chloride". Inorganic Chemistry 17 (5): 1376–1377. doi:10.1021/ic50183a059.

- ↑ Brehler, B. (1961). "Kristallstrukturuntersuchungen an ZnCl2". Zeitschrift für Kristallographie 115 (5–6): 373–402. doi:10.1524/zkri.1961.115.5-6.373. Bibcode: 1961ZK....115..373B.

- ↑ Mackenzie, J. D.; Murphy, W. K. (1960). "Structure of Glass-Forming Halides. II. Liquid Zinc Chloride". The Journal of Chemical Physics 33 (2): 366–369. doi:10.1063/1.1731151. Bibcode: 1960JChPh..33..366M.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Prince, R. H. (1994). King, R. B.. ed. Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-93620-6.

- ↑ Ray, H. S. (2006). Introduction to Melts: Molten Salts, Slags and Glasses. Allied Publishers. ISBN 978-81-7764-875-1.

- ↑ Danek, V. (2006). Physico-Chemical Analysis of Molten Electrolytes. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-52116-3.

- ↑ Price, D. L.; Saboungi, M.-L.; Susman, S.; Volin, K. J.; Wright, A. C. (1991). "Neutron Scattering Function of Vitreous and Molten Zinc Chloride". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 3 (49): 9835–9842. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/3/49/001. Bibcode: 1991JPCM....3.9835P.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ↑ Glenn J. McGarvey Jean-François Poisson Sylvain Taillemaud (2016). "Zinc chloride". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis: 1–20. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rz007.pub3. ISBN 9780470842898.

- ↑ Pray, A. P. (1990). Anhydrous Metal Chlorides. Inorganic Syntheses. 28. pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Organic Synthesis Highlights. 3. Wiley-VCH. 1998. ISBN 978-3-527-29500-5.

- ↑ Bouma, R. J.; Teuben, J. H.; Beukema, W. R.; Bansemer, R. L.; Huffman, J. C.; Caulton, K. G. (1984). "Identification of the Zinc Reduction Product of VCl3 · 3THF as [V2Cl3(THF)6]2[Zn2Cl6]". Inorganic Chemistry 23 (17): 2715–2718. doi:10.1021/ic00185a033.

- ↑ Irish, D. E.; McCarroll, B.; Young, T. F. (1963). "Raman Study of Zinc Chloride Solutions". The Journal of Chemical Physics 39 (12): 3436–3444. doi:10.1063/1.1734212. Bibcode: 1963JChPh..39.3436I.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, T.; Hayashi, S.; Ohtaki, H. (1989). "X-Ray Diffraction and Raman Studies of Zinc(II) Chloride Hydrate Melts, ZnCl2 · R H2O (R = 1.8, 2.5, 3.0, 4.0, and 6.2)". The Journal of Physical Chemistry 93 (6): 2620–2625. doi:10.1021/j100343a074.

- ↑ Pye, C. C.; Corbeil, C. R.; Rudolph, W. W. (2006). "An ab initio Investigation of Zinc Chloro Complexes". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 8 (46): 5428–5436. doi:10.1039/b610084h. ISSN 1463-9076. PMID 17119651. Bibcode: 2006PCCP....8.5428P.

- ↑ Brown, I. D. (2006). The Chemical Bond in Inorganic Chemistry: The Bond Valence Model. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929881-5.

- ↑ Zhang, X. G. (1996). Corrosion and Electrochemistry of Zinc. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-45334-2. Staff writer(s). "Simonkolleite Mineral Data". http://webmineral.com/data/Simonkolleite.shtml#.VEA-9SLF-vM.

- ↑ Feigl, F.; Caldas, A. (1956). "Some Applications of Fusion Reactions with Zinc Chloride in Inorganic Spot Test Analysis". Microchimica Acta 44 (7–8): 1310–1316. doi:10.1007/BF01257465.

- ↑ Vulte, H. T. (2007). Laboratory Manual of Inorganic Preparations. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4086-0840-1.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, T.; Lindqvist, O. (1981). "The Crystal Structure of Diamminedichlorozinc(II), ZnCl2(NH3)2. A New Refinement". Acta Chemica Scandinavica A 35 (9): 727–728. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.35a-0727. http://actachemscand.org/pdf/acta_vol_35a_p0727-0728.pdf.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, T.; Ohtaki, H. (1978). "X-Ray Diffraction Studies on the Structures of Tetraammine- and Triamminemonochlorozinc(II) Ions in Aqueous Solution". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan 51 (11): 3227–3231. doi:10.1246/bcsj.51.3227.

- ↑ Wilson, A. D.; Nicholson, J. W. (1993). Acid-Base Cements: Their Biomedical and Industrial Applications. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37222-0.

- ↑ House, J. E. (2008). Inorganic Chemistry. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-356786-4.

- ↑ Mellow, J. W. (1946). A Comprehensive Treatise on Inorganic and Theoretical Chemistry. Longmans, Green.

- ↑ Xu, Q.; Chen, L.-F. (1999). "Ultraviolet Spectra and Structure of Zinc-Cellulose Complexes in Zinc Chloride Solution". Journal of Applied Polymer Science 71 (9): 1441–1446. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19990228)71:9<1441::AID-APP8>3.0.CO;2-G.

- ↑ Fischer, S.; Leipner, H.; Thümmler, K.; Brendler, E.; Peters, J. (2003). "Inorganic Molten Salts as Solvents for Cellulose". Cellulose 10 (3): 227–236. doi:10.1023/A:1025128028462.

- ↑ Olah, George A.; Doggweiler, Hans; Felberg, Jeff D.; Frohlich, Stephan; Grdina, Mary Jo; Karpeles, Richard; Keumi, Takashi; Inaba, Shin-ichi et al. (1984). "Onium Ylide chemistry. 1. Bifunctional acid-base-catalyzed conversion of heterosubstituted methanes into ethylene and derived hydrocarbons. The onium ylide mechanism of the C1 → C2 conversion". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106 (7): 2143–2149. doi:10.1021/ja00319a039.

- ↑ Chang, Clarence D. (1983). "Hydrocarbons from Methanol". Catal. Rev. - Sci. Eng. 25 (1): 1–118. doi:10.1080/01614948308078874.

- ↑ Shriner, R. L.; Ashley, W. C.; Welch, E. (1942). "2-Phenylindole". Organic Syntheses 22: 98. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.022.00981955. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=cv3p0725.; Collective Volume, 3, pp. 725

- ↑ Cooper, S. R. (1941). "Resacetophenone". Organic Syntheses 21: 103. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.021.0103. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=cv3p0761.; Collective Volume, 3, pp. 761

- ↑ Dike, S. Y.; Merchant, J. R.; Sapre, N. Y. (1991). "A New and Efficient General Method for the Synthesis of 2-Spirobenzopyrans: First Synthesis of Cyclic Analogues of Precocene I and Related Compounds". Tetrahedron 47 (26): 4775–4786. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)86481-4.

- ↑ Furnell, B. S. (1989). Vogel's Textbook of Practical Organic Chemistry (5th ed.). New York: Longman/Wiley.

- ↑ Bauml, E.; Tschemschlok, K.; Pock, R.; Mayr, H. (1988). "Synthesis of γ-Lactones from Alkenes Employing p-Methoxybenzyl Chloride as +CH2-CO2− Equivalent". Tetrahedron Letters 29 (52): 6925–6926. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)88476-2. http://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/3799/1/086.pdf.

- ↑ Kim, S.; Kim, Y. J.; Ahn, K. H. (1983). "Selective Reduction of Tertiary, Allyl, and Benzyl Halides by Zinc-Modified Cyanoborohydride in Diethyl Ether". Tetrahedron Letters 24 (32): 3369–3372. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)86272-3.

- ↑ House, H. O.; Crumrine, D. S.; Teranishi, A. Y.; Olmstead, H. D. (1973). "Chemistry of Carbanions. XXIII. Use of Metal Complexes to Control the Aldol Condensation". Journal of the American Chemical Society 95 (10): 3310–3324. doi:10.1021/ja00791a039.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Wiberg, Nils (2007) (in de). Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie. de Gruyter, Berlin. p. 1491. ISBN 978-3-11-017770-1.

- ↑ American Society for Metals (1990). ASM handbook. ASM International. ISBN 978-0-87170-021-6.

- ↑ Sample, B. E. (1997). Methods for Field Studies of Effects of Military Smokes, Obscurants, and Riot-control Agents on Threatened and Endangered Species. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4289-1233-5.

- ↑ Menzel, E. R. (1999). Fingerprint Detection with Lasers. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8247-1974-6.

- ↑ Watts, H. (1869). A Dictionary of Chemistry and the Allied Branches of Other Sciences. Longmans, Green. https://archive.org/details/adictionarychem11wattgoog.

- ↑ McLean, David (April 2010). "Protecting wood and killing germs: 'Burnett's Liquid' and the origins of the preservative and disinfectant industries in early Victorian Britain". Business History 52 (2): 285–305. doi:10.1080/00076791003610691.

- ↑ "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards". https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0674.html.

Further reading

- N. N. Greenwood, A. Earnshaw, Chemistry of the Elements, 2nd ed., Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK, 1997.

- Lide, D. R., ed (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- The Merck Index, 7th edition, Merck & Co, Rahway, New Jersey, USA, 1960.

- D. Nicholls, Complexes and First-Row Transition Elements, Macmillan Press, London, 1973.

- J. March, Advanced Organic Chemistry, 4th ed., p. 723, Wiley, New York, 1992.

- G. J. McGarvey, in Handbook of Reagents for Organic Synthesis, Volume 1: Reagents, Auxiliaries and Catalysts for C-C Bond Formation, (R. M. Coates, S. E. Denmark, eds.), pp. 220–3, Wiley, New York, 1999.

External links

|