Chemistry:Manganese dioxide

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Manganese dioxide

Manganese(IV) oxide | |

| Other names

Pyrolusite, hyperoxide of manganese, black oxide of manganese, manganic oxide

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| MnO2 | |

| Molar mass | 86.9368 g/mol |

| Appearance | Brown-black solid |

| Density | 5.026 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 535 °C (995 °F; 808 K) (decomposes) |

| Insoluble | |

| +2280.0×10−6 cm3/mol[1] | |

| Structure[2] | |

| Tetragonal, tP6, No. 136 | |

| P42/mnm | |

a = 0.44008 nm, b = 0.44008 nm, c = 0.28745 nm

| |

Formula units (Z)

|

2 |

| Thermochemistry[3] | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

54.1 J·mol−1·K−1 |

Std molar

entropy (S |

53.1 J·mol−1·K−1 |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−520.0 kJ·mol−1 |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG˚)

|

−465.1 kJ·mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 0175 |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Warning |

| H302, H332 | |

| P261, P264, P270, P271, P301+312, P304+312, P304+340, P312, P330, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 535 °C (995 °F; 808 K) |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Manganese disulfide |

Other cations

|

Technetium dioxide Rhenium dioxide |

| Manganese(II) oxide Manganese(II,III) oxide Manganese(III) oxide Manganese heptoxide | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Manganese dioxide is the inorganic compound with the formula MnO2. This blackish or brown solid occurs naturally as the mineral pyrolusite, which is the main ore of manganese and a component of manganese nodules. The principal use for MnO2 is for dry-cell batteries, such as the alkaline battery and the zinc–carbon battery, although it is also used for other battery chemistries such as aqueous zinc-ion batteries.[4][5] MnO2 is also used as a pigment and as a precursor to other manganese compounds, such as potassium permanganate (KMnO

4). It is used as a reagent in organic synthesis, for example, for the oxidation of allylic alcohols. MnO2 has an α-polymorph that can incorporate a variety of atoms (as well as water molecules) in the "tunnels" or "channels" between the manganese oxide octahedra. There is considerable interest in α-MnO2 as a possible cathode for lithium-ion batteries.[6][7]

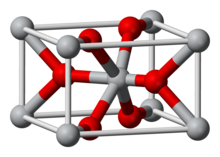

Structure

Several polymorphs of MnO2 are claimed, as well as a hydrated form. Like many other dioxides, MnO2 crystallizes in the rutile crystal structure (this polymorph is called pyrolusite or β-MnO2), with three-coordinate oxide anions and octahedral metal centres.[4] MnO2 is characteristically nonstoichiometric, being deficient in oxygen. The complicated solid-state chemistry of this material is relevant to the lore of "freshly prepared" MnO2 in organic synthesis.[8] The α-polymorph of MnO2 has a very open structure with "channels", which can accommodate metal ions such as silver or barium. α-MnO2 is often called hollandite, after a closely related mineral. Two other polymorphs, Todorokite and Romanechite MnO2, have a similar structure to α-MnO2 but with larger channels. δ-MnO2 exhibits a layered structure more akin to that of graphite.[5]

Production

Naturally occurring manganese dioxide contains impurities and a considerable amount of manganese(III) oxide. Production of batteries and ferrite (two of the primary uses of manganese dioxide) requires high purity manganese dioxide. Batteries require "electrolytic manganese dioxide" while ferrites require "chemical manganese dioxide".[9]

Chemical manganese dioxide

One method starts with natural manganese dioxide and converts it using dinitrogen tetroxide and water to a manganese(II) nitrate solution. Evaporation of the water leaves the crystalline nitrate salt. At temperatures of 400 °C, the salt decomposes, releasing N2O4 and leaving a residue of purified manganese dioxide.[9] These two steps can be summarized as:

- MnO2 + N2O4 ⇌ Mn(NO3)2

In another process, manganese dioxide is carbothermically reduced to manganese(II) oxide which is dissolved in sulfuric acid. The filtered solution is treated with ammonium carbonate to precipitate MnCO3. The carbonate is calcined in air to give a mixture of manganese(II) and manganese(IV) oxides. To complete the process, a suspension of this material in sulfuric acid is treated with sodium chlorate. Chloric acid, which forms in situ, converts any Mn(III) and Mn(II) oxides to the dioxide, releasing chlorine as a by-product.[9]

Lastly, the action of potassium permanganate over manganese sulfate crystals produces the desired oxide.[10]

- 2 KMnO4 + 3 MnSO4 + 2 H2O→ 5 MnO2 + K2SO4 + 2 H2SO4

Electrolytic manganese dioxide

Electrolytic manganese dioxide (EMD) is used in zinc–carbon batteries together with zinc chloride and ammonium chloride. EMD is commonly used in zinc manganese dioxide rechargeable alkaline (Zn RAM) cells also. For these applications, purity is extremely important. EMD is produced in a similar fashion as electrolytic tough pitch (ETP) copper: The manganese dioxide is dissolved in sulfuric acid (sometimes mixed with manganese sulfate) and subjected to a current between two electrodes. The MnO2 dissolves, enters solution as the sulfate, and is deposited on the anode.[11]

Reactions

The important reactions of MnO2 are associated with its redox, both oxidation and reduction.

Reduction

MnO2 is the principal precursor to ferromanganese and related alloys, which are widely used in the steel industry. The conversions involve carbothermal reduction using coke:[12]

- MnO2 + 2 C → Mn + 2 CO

The key redox reactions of MnO2 in batteries is the one-electron reduction:

- MnO2 + e− + H+ → MnO(OH)

MnO2 catalyses several reactions that form O2. In a classical laboratory demonstration, heating a mixture of potassium chlorate and manganese dioxide produces oxygen gas. Manganese dioxide also catalyses the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to oxygen and water:

- 2 H2O2 → 2 H2O + O2

Manganese dioxide decomposes above about 530 °C to manganese(III) oxide and oxygen. At temperatures close to 1000 °C, the mixed-valence compound Mn3O4 forms. Higher temperatures give MnO, which is reduced only with difficulty.[12]

Hot concentrated sulfuric acid reduces MnO2 to manganese(II) sulfate:[4]

- 2 MnO2 + 2 H2SO4 → 2 MnSO4 + O2 + 2 H2O

The reaction of hydrogen chloride with MnO2 was used by Carl Wilhelm Scheele in the original isolation of chlorine gas in 1774. Scheele treated sodium chloride with concentrated sulfuric acid:[4]

- MnO2 + 4 HCl → MnCl2 + Cl2 + 2 H2O

Standard electrode potentials suggest that the reaction would not proceed...

- E

o(MnO2(s) + 4 H+ + 2 e− ⇌ Mn2+ + 2 H2O) = +1.23 V - E

o(Cl2(g) + 2 e− ⇌ 2 Cl−) = +1.36 V

...but it is favoured by the extremely high acidity and the evolution (and removal) of gaseous chlorine.

This reaction is also a convenient way to remove the manganese dioxide precipitate from the ground glass joints after running a reaction (for example, an oxidation with potassium permanganate).

Oxidation

Heating a mixture of KOH and MnO2 in air gives green potassium manganate:

- 2 MnO2 + 4 KOH + O2 → 2 K2MnO4 + 2 H2O

Potassium manganate is the precursor to potassium permanganate, a common oxidant.

Occurrence and applications

Prehistory

Excavations at the Pech-de-l'Azé cave site in southwestern France have yielded blocks of manganese dioxide writing tools, which date back 50,000 years and have been attributed to Neanderthals . Scientists have conjectured that Neanderthals used this mineral for body decoration, but there are many other readily available minerals that are more suitable for that purpose. Heyes et al. (in 2016) determined that the manganese dioxide lowers the combustion temperatures for wood from above 350°C (662°F) to 250°C (482°F), making fire making much easier and this is likely to be the purpose of the blocks.[13]

Batteries

The predominant application of MnO2 is as a component of dry cell batteries: alkaline batteries and so called Leclanché cell, or zinc–carbon batteries. Approximately 500,000 tonnes are consumed for this application annually.[14]

δ-MnO2 has also been researched as the primary cathode material for aqueous zinc-ion battery systems. Such cathodes often contain additives to address structural, kinetic, and conductivity-based issues. These carbon additives can include reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and carbon nanotubes, among others.[15]

Organic synthesis

A specialized use of manganese dioxide is as oxidant in organic synthesis.[8] The effectiveness of the reagent depends on the method of preparation, a problem that is typical for other heterogeneous reagents where surface area, among other variables, is a significant factor.[16] The mineral pyrolusite makes a poor reagent. Usually, however, the reagent is generated in situ by treatment of an aqueous solution KMnO4 with a Mn(II) salt, typically the sulfate. MnO2 oxidizes allylic alcohols to the corresponding aldehydes or ketones:[17]

- cis-RCH=CHCH2OH + MnO2 → cis-RCH=CHCHO + MnO + H2O

The configuration of the double bond is conserved in the reaction. The corresponding acetylenic alcohols are also suitable substrates, although the resulting propargylic aldehydes can be quite reactive. Benzylic and even unactivated alcohols are also good substrates. 1,2-Diols are cleaved by MnO2 to dialdehydes or diketones. Otherwise, the applications of MnO2 are numerous, being applicable to many kinds of reactions including amine oxidation, aromatization, oxidative coupling, and thiol oxidation.

Other potential applications

In Geobacteraceae sp., MnO2 functions as an electron acceptor coupled to the oxidation of organic compounds. This theme has possible implications for bioremediation within the field of microbiology.[18]

MnO2 is used as an inorganic pigment in ceramics and in glassmaking.

See also

References

- ↑ Rumble, p. 4.71

- ↑ Haines, J.; Léger, J.M.; Hoyau, S. (1995). "Second-order rutile-type to CaCl2-type phase transition in β-MnO2 at high pressure". Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 56 (7): 965–973. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(95)00037-2. Bibcode: 1995JPCS...56..965H.

- ↑ Rumble, p. 5.25

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford: Pergamon Press. pp. 1218–20. ISBN 978-0-08-022057-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=OezvAAAAMAAJ&q=0-08-022057-6&dq=0-08-022057-6&source=bl&ots=m4tIRxdwSk&sig=XQTTjw5EN9n5z62JB3d0vaUEn0Y&hl=en&sa=X&ei=UoAWUN7-EM6ziQfyxIDoCQ&ved=0CD8Q6AEwBA..

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Shi, Wen; Lee, Wee Siang Vincent; Xue, Junmin (2021-04-09). "Recent Development of Mn‐based Oxides as Zinc‐Ion Battery Cathode" (in en). ChemSusChem 14 (7): 1634–1658. doi:10.1002/cssc.202002493. ISSN 1864-5631. https://chemistry-europe.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cssc.202002493.

- ↑ Barbato, S (31 May 2001). "Hollandite cathodes for lithium ion batteries. 2. Thermodynamic and kinetics studies of lithium insertion into BaMMn7O16 (M=Mg, Mn, Fe, Ni)". Electrochimica Acta 46 (18): 2767–2776. doi:10.1016/S0013-4686(01)00506-0.

- ↑ Tompsett, David A.; Islam, M. Saiful (25 June 2013). "Electrochemistry of Hollandite α-MnO: Li-Ion and Na-Ion Insertion and Li Incorporation". Chemistry of Materials 25 (12): 2515–2526. doi:10.1021/cm400864n.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Cahiez, G.; Alami, M.; Taylor, R. J. K.; Reid, M.; Foot, J. S. (2004), "Manganese Dioxide", in Paquette, Leo A., Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis, New York: J. Wiley & Sons, pp. 1–16, doi:10.1002/047084289X.rm021.pub4, ISBN 978-0-470-84289-8.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Preisler, Eberhard (1980), "Moderne Verfahren der Großchemie: Braunstein", Chemie in unserer Zeit 14 (5): 137–48, doi:10.1002/ciuz.19800140502.

- ↑ Arthur Sutcliffe (1930) Practical Chemistry for Advanced Students (1949 Ed.), John Murray – London.

- ↑ Biswal, Avijit; Chandra Tripathy, Bankim; Sanjay, Kali; Subbaiah, Tondepu; Minakshi, Manickam (2015). "Electrolytic manganese dioxide (EMD): A perspective on worldwide production, reserves and its role in electrochemistry". RSC Advances 5 (72): 58255–58283. doi:10.1039/C5RA05892A. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2015/ra/c5ra05892a.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Wellbeloved, David B.; Craven, Peter M.; Waudby, John W. (2000). "Manganese and Manganese Alloys". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_077. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ↑ "Neandertals may have used chemistry to start fires" (in en). https://www.science.org/content/article/neandertals-may-have-used-chemistry-start-fires.

- ↑ Reidies, Arno H. (2002), "Manganese Compounds", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 20, Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, pp. 495–542, doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_123, ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4

- ↑ Azmi, Zarina; Senapati, Krushna C.; Goswami, Arpan K.; Mohapatra, Saumya R. (September 2024). "A Comprehensive Review of Strategies to Augment the Performance of MnO2 Cathode by Structural Modifications for Aqueous Zinc Ion Battery" (in en). Journal of Power Sources 613. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2024.234816. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0378775324007687.

- ↑ Attenburrow, J.; Cameron, A. F. B.; Chapman, J. H.; Evans, R. M.; Hems, B. A.; Jansen, A. B. A.; Walker, T. (1952), "A synthesis of vitamin a from cyclohexanone", J. Chem. Soc.: 1094–1111, doi:10.1039/JR9520001094.

- ↑ Paquette, Leo A. and Heidelbaugh, Todd M.. "(4S)-(−)-tert-Butyldimethylsiloxy-2-cyclopen-1-one". Organic Syntheses. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=cv9p0136.; Collective Volume, 9, pp. 136 (this procedure illustrates the use of MnO2 for the oxidation of an allylic alcohol)

- ↑ Lovley, Derek R.; Holmes, Dawn E.; Nevin, Kelly P. (2004). Dissimilatory Fe(III) and Mn(IV) Reduction. Advances in Microbial Physiology. 49. pp. 219–286. doi:10.1016/S0065-2911(04)49005-5. ISBN 978-0-12-027749-0.

Cited sources

External links

- Index of Organic Synthesis procedures utilizing MnO2

- Example Reactions with Mn(IV) oxide

- National Pollutant Inventory – Manganese and compounds Fact Sheet

- PubChem summary of MnO2

- International Chemical Safety Card 0175

- Potters Manganese Toxicity by Elke Blodgett

- The reaction between manganese dioxide and potassium permanganate (1893) by A. J. Hopkins

|