Chemistry:Hydroxymethylfurfural

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

5-(Hydroxymethyl)furan-2-carbaldehyde[1] | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 110889 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| EC Number |

|

| 278693 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H6O3 | |

| Molar mass | 126.111 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Low melting white solid |

| Odor | Buttery, caramel |

| Density | 1.29 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 30 to 34 °C (86 to 93 °F; 303 to 307 K) |

| Boiling point | 114 to 116 °C (237 to 241 °F; 387 to 389 K) (1 mbar) |

| UV-vis (λmax) | 284 nm[2] |

| Related compounds | |

Related furan-2-carbaldehydes

|

Furfural |

| Hazards | |

| GHS pictograms |  [3] [3]

|

| GHS Signal word | Warning[3] |

| H315, H319, H335[3] | |

| P261, P305+351+338, P310[3] | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

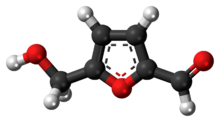

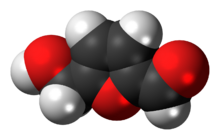

Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), also known as 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural, is an organic compound formed by the dehydration of reducing sugars.[4][5] It is a white low-melting solid (although commercial samples are often yellow) which is highly soluble in both water and organic solvents. The molecule consists of a furan ring, containing both aldehyde and alcohol functional groups.

HMF can form in sugar-containing food, particularly as a result of heating or cooking. Its formation has been the topic of significant study as HMF was regarded as being potentially carcinogenic to humans. However, so far in vivo genotoxicity was negative. No relevance for humans concerning carcinogenic and genotoxic effects can be derived.[6] HMF is classified as a food improvement agent [7] and is primarily being used in the food industry in form of a food additive as a biomarker as well as a flavoring agent for food products.[8][9] It is also produced industrially on a modest scale[10] as a carbon-neutral feedstock for the production of fuels[11] and other chemicals.[12]

Production and reactions

HMF was first reported in 1875 as an intermediate in the formation of levulinic acid from sugar and sulfuric acid.[13] This remains the classical route, with 6-carbon sugars (hexoses) such as fructose undergoing acid catalyzed poly-dehydration.[14][15] When hydrochloric acid is used 5-chloromethylfurfural is produced instead of HMF. Similar chemistry is seen with 5-carbon sugars (pentoses), which react with aqueous acid to form furfural.

The classical approach tends to suffer from poor yields as HMF continues to react in aqueous acid, forming levulinic acid.[4] As sugar is not generally soluble in solvents other than water, the development of high-yielding reactions has been slow and difficult; hence while furfural has been produced on a large scale since the 1920s,[16] HMF was not produced on a commercial scale until over 90 years later. The first production plant coming online in 2013.[10] Numerous synthetic technologies have been developed, including the use of ionic liquids,[17][18] continuous liquid-liquid extraction, reactive distillation and solid acid catalysts to either remove the HMF before it reacts further or to otherwise promote its formation and inhibit its decomposition.[19]

Derivatives

HMF itself has few applications. It can however be converted into other more useful compounds.[12] Of these the most important is 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid, which has been proposed as a replacement for terephthalic acid in the production of polyesters.[20][21] HMF can be converted to 2,5-dimethylfuran (DMF), a liquid that is a potential biofuel with a greater energy content than bioethanol. Hydrogenation of HMF gives 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan. Acid-catalysed hydrolysis converts HMF into gamma-hydroxyvaleric acid and gamma-valerolactone, with loss of formic acid.[5][4]

Occurrence in food

HMF is practically absent in fresh food, but it is naturally generated in sugar-containing food during heat-treatments like drying or cooking. Along with many other flavor- and color-related substances, HMF is formed in the Maillard reaction as well as during caramelization. In these foods it is also slowly generated during storage. Acid conditions favour generation of HMF.[22] HMF is a well known component of baked goods. Upon toasting bread, the amount increases from 14.8 (5 min.) to 2024.8 mg/kg (60 min).[5] It is also formed during coffee roasting, with up to 769 mg/kg.[23]

It is a good wine storage time−temperature marker,[24] especially in sweet wines such as Madeira[25] and those sweetened with grape concentrate arrope.[26]

HMF can be found in low amounts in honey, fruit-juices and UHT-milk. Here, as well as in vinegars, jams, alcoholic products or biscuits, HMF can be used as an indicator for excess heat-treatment. For instance, fresh honey contains less than 15 mg/kg—depending on pH-value and temperature and age,[27] and the codex alimentarius standard requires that honey have less than 40 mg/kg HMF to guarantee that the honey has not undergone heating during processing, except for tropical honeys which must be below 80 mg/kg.[28]

Higher quantities of HMF are found naturally in coffee and dried fruit. Several types of roasted coffee contained between 300 – 2900 mg/kg HMF.[29] Dried plums were found to contain up to 2200 mg/kg HMF. In dark beer 13.3 mg/kg were found,[30] bakery-products contained between 4.1 – 151 mg/kg HMF.[31]

It can be found in glucose syrup.

HMF can form in high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), levels around 20 mg/kg HMF were found, increasing during storage or heating.[27] This is a problem for American beekeepers because they use HFCS as a source of sugar when there are not enough nectar sources to feed honeybees, and HMF is toxic to them. Adding bases such as soda ash or potash to neutralize the HFCS slows the formation of HMF.[27]

Depending on production-technology and storage, levels in food vary considerably. To evaluate the contribution of a food to HMF intake, its consumption-pattern has to be considered. Coffee is the food that has a very high relevance in terms of levels of HMF and quantities consumed.

HMF is a natural component in heated food but usually present in low concentrations. The daily intake of HMF may underlie high variations due to individual consumption-patterns. It has been estimated that the intakes range between 4 mg - 30 mg per person per day, while an intake of up to 350 mg can result from, e.g., beverages made from dried plums.[6][32]

Biomedical

A major metabolite in humans is 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furoic acid (HMFA), also known as Sumiki's acid, which is excreted in urine.

HMF bind intracellular sickle hemoglobin (HbS). Preliminary in vivo studies using transgenic sickle mice showed that orally administered 5HMF inhibits the formation of sickled cells in the blood.[33] Under the development code Aes-103, HMF has been considered for the treatment of sickle cell disease.[34]

Quantification

Today, HPLC with UV-detection is the reference-method (e.g. DIN 10751–3). Classic methods for the quantification of HMF in food use photometry. The method according to White is a differential UV-photometry with and without sodium bisulfite-reduction of HMF.[35] Winkler photometric method is a colour-reaction using p-toluidine and barbituric acid (DIN 10751–1). Photometric test may be unspecific as they may detect also related substances, leading to higher results than HPLC-measurements. Test-kits for rapid analyses are also available (e.g. Reflectoquant HMF, Merck KGaA).[36][37]

Other

HMF is an intermediate in the titration of hexoses in the Molisch's test. In the related Bial's test for pentoses, the hydroxymethylfurfural from hexoses may give a muddy-brown or gray solution, but this is easily distinguishable from the green color of pentoses.

Acetoxymethyl furfural (AMF) is also bio-derived green platform chemicals as an alternative to HMF.[38]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Front Matter". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 911. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ↑ The Determination of HMF in Honey with an Evolution Array UV-Visible Spectrophotometer. Nicole Kreuziger Keppy and Michael W. Allen, Ph.D., Application note 51864, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, WI, USA (article)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Sigma-Aldrich Co., 5-(Hydroxymethyl)furfural.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 van Putten, Robert-Jan; van der Waal, Jan C.; de Jong, Ed; Rasrendra, Carolus B.; Heeres, Hero J.; de Vries, Johannes G. (2013). "Hydroxymethylfurfural, A Versatile Platform Chemical Made from Renewable Resources". Chemical Reviews 113 (3): 1499–1597. doi:10.1021/cr300182k. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 23394139.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Rosatella, Andreia A.; Simeonov, Svilen P.; Frade, Raquel F. M.; Afonso, Carlos A. M. (2011). "5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) as a building block platform: Biological properties, synthesis and synthetic applications". Green Chemistry 13 (4): 754. doi:10.1039/c0gc00401d. ISSN 1463-9262.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Abraham, Klaus; Gürtler, Rainer; Berg, Katharina; Heinemeyer, Gerhard; Lampen, Alfonso; Appel, Klaus E. (2011-04-04). "Toxicology and risk assessment of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural in food". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 55 (5): 667–678. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201000564. ISSN 1613-4125. PMID 21462333.

- ↑ PubChem. "EU Food Improvement Agents - PubChem Data Source". https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/source/EU%20Food%20Improvement%20Agents.

- ↑ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 872/2012 of 1 October 2012 adopting the list of flavouring substances provided for by Regulation (EC) No 2232/96 of the European Parliament and of the Council, introducing it in Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 1334/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 1565/2000 and Commission Decision 1999/217/EC Text with EEA relevance, 2012-10-02, http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2012/872/oj/eng, retrieved 2018-06-25

- ↑ Pubchem. "5-(Hydroxymethyl)-2-furaldehyde". https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/237332#section=Top.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kläusli, Thomas (2014). "AVA Biochem: commercialising renewable platform chemical 5-HMF". Green Processing and Synthesis 3 (3): 235–236. doi:10.1515/gps-2014-0029. ISSN 2191-9550.

- ↑ Huber, George W.; Iborra, Sara; Corma, Avelino (2006). "Synthesis of Transportation Fuels from Biomass: Chemistry, Catalysts, and Engineering". Chem. Rev. 106 (9): 4044–98. doi:10.1021/cr068360d. PMID 16967928. https://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1058&context=george_huber.MIT Technology Review

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lewkowski, J. (2001). "Synthesis, chemistry and applications of 5-hydroxymethyl-furfural and its derivatives". Arkivoc 1: 17–54. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0002.102. ISSN 1424-6376.

- ↑ Grote, A. Freiherrn V.; Tollens, B. (1875). "Untersuchungen über Kohlenhydrate. I. Ueber die bei Einwirkung von Schwefelsäure auf Zucker entstehende Säure (Levulinsäure)". Justus Liebig's Annalen der Chemie 175 (1–2): 181–204. doi:10.1002/jlac.18751750113. ISSN 0075-4617. https://zenodo.org/record/1427341.

- ↑ Yuriy Román-Leshkov; Juben N. Chheda; James A. Dumesic (2006). "Phase Modifiers Promote Efficient Production of Hydroxymethylfurfural from Fructose". Science 312 (5782): 1933–1937. doi:10.1126/science.1126337. PMID 16809536. Bibcode: 2006Sci...312.1933R.

- ↑ Simeonov, Svilen (2016). "Synthesis of 5-(Hydroxymethyl)furfural (HMF)". Organic Syntheses 93: 29–36. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.093.0029.

- ↑ Brownlee, Harold J.; Miner, Carl S. (1948). "Industrial Development of Furfural". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry 40 (2): 201–204. doi:10.1021/ie50458a005. ISSN 0019-7866.

- ↑ Zakrzewska, Małgorzata E.; Bogel-Łukasik, Ewa; Bogel-Łukasik, Rafał (2011). "Ionic Liquid-Mediated Formation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural—A Promising Biomass-Derived Building Block". Chemical Reviews 111 (2): 397–417. doi:10.1021/cr100171a. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 20973468.

- ↑ Eminov, Sanan; Wilton-Ely, James D. E. T.; Hallett, Jason P. (2 March 2014). "Highly Selective and Near-Quantitative Conversion of Fructose to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Using Mildly Acidic Ionic Liquids". ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2 (4): 978–981. doi:10.1021/sc400553q.

- ↑ Teong, Siew Ping; Yi, Guangshun; Zhang, Yugen (2014). "Hydroxymethylfurfural production from bioresources: past, present and future". Green Chemistry 16 (4): 2015. doi:10.1039/c3gc42018c. ISSN 1463-9262.

- ↑ Sousa, Andreia F.; Vilela, Carla; Fonseca, Ana C.; Matos, Marina; Freire, Carmen S. R.; Gruter, Gert-Jan M.; Coelho, Jorge F. J.; Silvestre, Armando J. D. (2015). "Biobased polyesters and other polymers from 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: a tribute to furan excellency". Polym. Chem. 6 (33): 5961–5983. doi:10.1039/C5PY00686D. ISSN 1759-9954.

- ↑ Zhang, Daihui; Dumont, Marie-Josée (1 May 2017). "Advances in polymer precursors and bio-based polymers synthesized from 5-hydroxymethylfurfural". Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 55 (9): 1478–1492. doi:10.1002/pola.28527. Bibcode: 2017JPoSA..55.1478Z.

- ↑ Arribas-Lorenzo, G; Morales, FJ (2010). "Estimation of dietary intake of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and related substances from coffee to Spanish population". Food and Chemical Toxicology 48 (2): 644–9. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2009.11.046. PMID 20005914.

- ↑ Macheiner, Lukas; Schmidt, Anatol; Karpf, Franz; Mayer, Helmut K. (2021). "A novel UHPLC method for determining the degree of coffee roasting by analysis of furans". Food Chemistry 341 (Pt 1): 128165. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128165. ISSN 0308-8146. PMID 33038777.

- ↑ Serra-Cayuela, A.; Jourdes, M.; Riu-Aumatell, M.; Buxaderas, S.; Teissedre, P.-L.; López-Tamames, E. (2014). "Kinetics of Browning, Phenolics, and 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural in Commercial Sparkling Wines". J. Agric. Food Chem. 62 (5): 1159–1166. doi:10.1021/jf403281y. PMID 24444020.

- ↑ Pereira, V. (2011). "Evolution of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) and furfural (F) in fortified wines submitted to overheating conditions". Food Research International 44: 71–76. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2010.11.011.

- ↑ Amerine, Maynard A. (1948). "Hydroxymethylfurfural in California Wines". Journal of Food Science 13 (3): 264–269. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1948.tb16621.x. PMID 18870652.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Ruiz-Matute, AI; Weiss, M; Sammataro, D; Finely, J; Sanz, ML (2010). "Carbohydrate composition of high-fructose corn syrups (HFCS) used for bee feeding: effect on honey composition". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 58 (12): 7317–22. doi:10.1021/jf100758x. PMID 20491475.

- ↑ Shapla, UM; Solayman, M; Alam, N; Khalil, MI; Gan, SH (2018). "5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) levels in honey and other food products: effects on bees and human health". Chem Cent J 12 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/s13065-018-0408-3. PMID 29619623.

- ↑ Murkovic, M; Pichler, N (2006). "Analysis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfual in coffee, dried fruits and urine". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 50 (9): 842–6. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200500262. PMID 16917810.

- ↑ Husøy, T; Haugen, M; Murkovic, M; Jöbstl, D; Stølen, LH; Bjellaas, T; Rønningborg, C; Glatt, H et al. (2008). "Dietary exposure to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from Norwegian food and correlations with urine metabolites of short-term exposure". Food and Chemical Toxicology 46 (12): 3697–702. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2008.09.048. PMID 18929614.

- ↑ Ramírez-Jiménez, A; Garcı́a-Villanova, Belén; Guerra-Hernández, Eduardo (2000). "Hydroxymethylfurfural and methylfurfural content of selected bakery products". Food Research International 33 (10): 833. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00102-2.

- ↑ Abraham, Klaus; Gürtler, Rainer; Berg, Katharina; Heinemeyer, Gerhard; Lampen, Alfonso; Appel, Klaus E. (May 2011). "Toxicology and risk assessment of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural in food". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 55 (5): 667–678. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201000564. ISSN 1613-4133. PMID 21462333.

- ↑ Abdulmalik, O; Safo, MK; Chen, Q; Yang, J; Brugnara, C; Ohene-Frempong, K; Abraham, DJ; Asakura, T (2005). "5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural modifies intracellular sickle haemoglobin and inhibits sickling of red blood cells". British Journal of Haematology 128 (4): 552–61. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05332.x. PMID 15686467.

- ↑ "Aes-103 for Sickle Cell Disease" (in en). 2015-03-18. https://ncats.nih.gov/trnd/projects/complete/aes-103-sickle-cell.

- ↑ White Jr., J. W. (1979). "Spectrophotometric method for hydroxymethylfurfural in honey". Journal of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists 62 (3): 509–514. doi:10.1093/jaoac/62.3.509. PMID 479072.

- ↑ Schultheiss, J.; Jensen, D.; Galensa, R. (2000). "Determination of aldehydes in food by high-performance liquid chromatography with biosensor coupling and micromembrane suppressors". Journal of Chromatography A 880 (1–2): 233–42. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(99)01086-9. PMID 10890522.

- ↑ Gaspar, Elvira M.S.M.; Lucena, Ana F.F. (2009). "Improved HPLC methodology for food control – furfurals and patulin as markers of quality". Food Chemistry 114 (4): 1576. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.11.097.

- ↑ Kang, Eun-Sil; Hong, Yeon-Woo; Chae, Da Won; Kim, Bora; Kim, Baekjin; Kim, Yong Jin; Cho, Jin Ku; Kim, Young Gyu (13 April 2015). "From Lignocellulosic Biomass to Furans via 5-Acetoxymethylfurfural as an Alternative to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural". ChemSusChem 8 (7): 1179–1188. doi:10.1002/cssc.201403252. ISSN 1864-564X. PMID 25619448.

|