Chemistry:Opioid epidemic

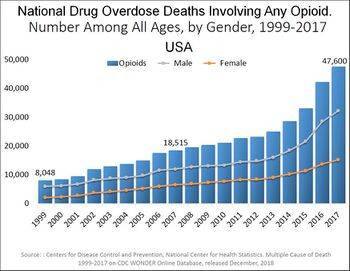

The opioid epidemic or opioids crisis is the rapid increase in the use of prescription and non-prescription opioid drugs in the United States and Canada beginning in the late 1990s and continuing throughout the next two decades. The increase in opioid overdose deaths has been dramatic, and opioids are now responsible for 49,000 of the 72,000 drug overdose deaths overall in the US in 2017.[2] A recent report indicated that the rate of prolong opioid use is increasing globally.[4] Opioids are a diverse class of moderately strong painkillers, including oxycodone (commonly sold under the trade names OxyContin and Percocet), hydrocodone (Vicodin, Norco), and a very strong painkiller, fentanyl, which is synthesized to resemble other opiates such as opium-derived morphine and heroin.

The potency and availability of these substances, despite their high risk of addiction and overdose, have made them popular both as medical treatments and as recreational drugs. Due to their sedative effects on the part of the brain which regulates breathing, the respiratory center of the medulla oblongata, opioids in high doses present the potential for respiratory depression, and may cause respiratory failure and death.[5]

In a 2015 report, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration stated that "overdose deaths, particularly from prescription drugs and heroin, have reached epidemic levels."[6]: iii Nearly half of all opioid overdose deaths in 2016 involved prescription opioids.[2][1] From 1999 to 2008, overdose death rates, sales, and substance abuse treatment admissions related to opioid pain relievers all increased substantially.[7] By 2015, there were more than 50,000 annual deaths from drug overdose, causing more deaths than either car accidents or guns.[8]

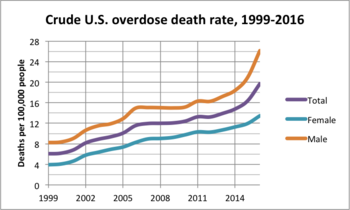

Drug overdoses have since become the leading cause of death of Americans under 50, with two-thirds of those deaths from opioids.[9] In 2016, the crisis decreased overall life expectancy of Americans for the second consecutive year.[10] Overall life expectancy fell from 78.7 to 78.6 years. Men were disproportionately more affected due to higher overdose death rates, with life expectancy declining from 76.3 to 76.1 years. Women's life expectancy remained stable at 81.1 years.[10]

In 2016, over 64,000 Americans died from overdoses, 21 percent more than the almost 53,000 in 2015.[9][11][12] By comparison, the figure was 16,000 in 2010, and 4,000 in 1999.[13][14] While death rates varied by state,[15] public health experts estimate that nationwide over 500,000 people could die from the epidemic over the next 10 years.[16] In Canada , half of the overdoses were accidental, while a third were intentional. The remainder were unknown.[17] Many of the deaths are from an extremely potent opioid, fentanyl, which is trafficked from Mexico.[18] The epidemic cost the United States an estimated $504 billion in 2015.[19]

CDC former director Thomas Frieden said that "America is awash in opioids; urgent action is critical."[20] The crisis has changed moral, social, and cultural resistance to street drug alternatives such as heroin.[21] Many state governors have declared a "state of emergency" to combat the opioid epidemic or undertook other major efforts against it.[22][23][24][25] In July 2017, opioid addiction was cited as the "FDA's biggest crisis".[26] In October 2017, President Donald Trump concurred with his Commission's report and declared the country's opioid crisis a "public health emergency".[27][28] Federal and state interventions are working on employing health information technology in order to expand the impact of existing drug monitoring programs.[29] Recent research shows promising results in mortality and morbidity reductions when a state integrates drug monitoring programs with health information technologies and shares data through centralized platform.[30]

History in North America

Mike Strobe, AP medical writer[31]

Opiates such as morphine have been used for pain relief in the United States since the 1800s, and were used during the American Civil War. Opiates soon became known as a wonder drug and were prescribed for a wide array of ailments, even for relatively minor treatments such as cough relief.[32] Bayer began marketing heroin commercially in 1898. Beginning around 1920, however, the addictiveness was recognized, and doctors became reluctant to prescribe opiates.[33] Heroin was made an illegal drug with the Anti-Heroin Act of 1924, in which the U.S. Congress banned the sale, importation, or manufacture of heroin.

In the 1950s, heroin addiction was known among jazz musicians, but still fairly uncommon among average Americans, many of whom saw it as a frightening condition.[21] The fear extended into the 1960s and 1970s, although it became common to hear or read about drugs such as marijuana and psychedelics, which were widely used at rock concerts like Woodstock.[21] Heroin addiction began to make the news around 1970 when rock star Janis Joplin died from an overdose. During and after the Vietnam War, addicted soldiers returned from Vietnam, where heroin was easily bought. Heroin addiction grew within low-income housing projects during the same time period.[21] In 1971, congressmen released an explosive report on the growing heroin epidemic among U.S. servicemen in Vietnam, finding that ten to fifteen percent were addicted to heroin. "The Nixon White House panicked," wrote political editor Christopher Caldwell, and declared drug abuse "public enemy number one".[34] By 1973, there were 1.5 overdose deaths per 100,000 people.[21]

Modern prescription opiates such as Vicodin and Percocet entered the market in the 1970s, but acceptance took several years and doctors were apprehensive about prescribing them.[32] Until the 1980s, physicians had been taught to avoid prescribing opioids because of their addictive nature.[33] A brief letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in January 1980, titled "Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics", generated much attention and changed this thinking.[35][36] A group of researchers in Canada claim that the letter may have originated and contributed to the opioid crisis.[35] The NEJM published its rebuttal to the 1980 letter in June 2017, pointing out among other things that the conclusions were based on hospitalized patients only, and not on patients taking the drugs after they were sent home.[37] The original author, Dr. Hershel Jick, has said that he never intended for the article to justify widespread opioid use.[35]

In the mid-to-late 1980s, the crack epidemic followed widespread cocaine use in American cities. The death rate was worse, reaching almost 2 per 100,000. In 1982, Vice President George H. W. Bush and his aides began pushing for the involvement of the CIA and the U.S. military in drug interdiction efforts, the so-called War on Drugs.[38] The initial promotion and marketing of OxyContin was an organized effort throughout 1996–2001, to dismiss the risk of opioid addiction. Purdue Pharma hosted over forty promotional conferences at three select locations in the southwest and southeast of the United States. Coupling a convincing "Partners Against Pain" campaign with an incentivized bonus system, Purdue trained its salesforce to convey the message that the risk of addiction was under one percent, ultimately influencing the prescribing habits of the medical professionals that attended these conferences.[39] In 2016, the opioid epidemic was killing on average 10.3 people per 100,000, with the highest rates including over 30 per 100,000 in New Hampshire and over 40 per 100,000 in West Virginia.[21]

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's National Survey on Drug Use and Health, in 2016 more than 11 million Americans misused prescription opioids, nearly 1 million used heroin, and 2.1 million had an addiction to prescription opioids or heroin.[40]

While rates of overdose of legal prescription opiates has leveled off in the past decade, overdoses of illicit opiates have surged since 2010, nearly tripling.[41]

Heroin

Between 4–6% of people who misuse prescription opioids turn to heroin, and 80% of heroin addicts began by abusing prescription opioids.[42] Many people addicted to opioids switch from taking prescription opioids to heroin because heroin is less expensive and more easily acquired on the black market.[43]

Men are more likely to overdose on heroin. Overall, opioids are among the biggest killers of every race.[44]

Heroin use has been increasing over the years. An estimated 374,000 Americans used heroin in 2002–2005, and this estimate grew to nearly double where 607,000 of Americans had used heroin in 2009–2011.[45] In 2014, it was estimated that more than half a million Americans had an addiction to heroin.[46]

Oxycodone

Oxycodone is the most widely used recreational opioid in the United States. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that about 11 million people in the U.S. consume oxycodone in a non-medical way annually.[47]

Oxycodone was first made available in the United States in 1939. In the 1970s, the FDA classified oxycodone as a Schedule II drug, indicating a high potential for abuse and addiction. In 1996, Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin, a controlled release formulation of oxycodone.[39] The FDA approved relabeling the reformulated version as abuse-resistant.[48] However, drug users quickly learned how to simply crush the controlled release tablet to swallow, inhale, or inject the high-strength opioid for a powerful morphine-like high. In fact, Purdue's private testing conducted in 1995 determined that 68% of the oxycodone could be extracted from an OxyContin tablet when crushed.[39]

In 2007, Purdue paid $600 million in fines after being prosecuted for making false claims about the risk of drug abuse associated with oxycodone.[49] In 2010, Purdue Pharma reformulated OxyContin, using a polymer to make the pills extremely difficult to crush or dissolve in water to reduce OxyContin abuse. OxyContin use following the 2010 reformulation declined slightly while no changes were observed in the use of other opioids.[50]

OxyContin was removed from the Canadian drug formulary in 2012.[51] In June 2017, the FDA asked the manufacturer to remove its injectable form of oxymorphone (Opana ER) from the US market, because the drug's benefits may no longer outweigh its risks, this being the first time the agency has asked to remove a currently marketed opioid pain medication from sale due to public health consequences of abuse.[52]

Fentanyl

Christopher Caldwell,

senior editor The Weekly Standard[21]

Fentanyl, a newer synthetic opioid painkiller, is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine and 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin,[21] with only 2 mg becoming a lethal dose. It is pure white, odorless and flavorless, with a potency strong enough that police and first responders helping overdose victims have themselves overdosed by simply touching or inhaling a small amount.[53][54][55] As a result, the DEA has recommended that officers not field test drugs if fentanyl is suspected, but instead collect and send samples to a laboratory for analysis. "Exposure via inhalation or skin absorption can be deadly," they state.[56]

Over a two-year period, close to $800 million worth of fentanyl pills were illegally sold online to the U.S. by Chinese distributors.[57][58] The drug is usually manufactured in China, then shipped to Mexico where it is processed and packaged, which is then smuggled into the U.S. by drug cartels. A large amount is also purchased online and shipped through the U.S. Postal Service.[59] It can also be purchased directly from China, which has become a major manufacturer of various synthetic drugs illegal in the U.S.[60] AP reporters found multiple sellers in China willing to ship carfentanyl, an elephant tranquilizer that is so potent it has been considered a chemical weapon. The sellers also offered advice on how to evade screening by US authorities.[61]

Deaths from fentanyl increased by 540 percent across the United States since 2015.[62] This accounts for almost "all the increase in drug overdose deaths from 2015 to 2016", according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.[41]

Fentanyl-laced heroin has become a big problem for major cities, including Philadelphia, Detroit and Chicago .[63] Its use has caused a spike in deaths among users of heroin and prescription painkillers, while becoming easier to obtain and conceal. Some arrested or hospitalized users are surprised to find that what they thought was heroin was actually fentanyl.[21] According to CDC director Thomas Frieden:

As overdose deaths involving heroin more than quadrupled since 2010, what was a slow stream of illicit fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, is now a flood, with the amount of the powerful drug seized by law enforcement increasing dramatically. America is awash in opioids; urgent action is critical.[20]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), death rates from synthetic opioids, including fentanyl, increased over 72% from 2014 to 2015.[64] In addition, the CDC reports that the total deaths from opioid overdoses may be under-counted, since they do not include deaths that are associated with synthetic opioids which are used as pain relievers. The CDC presumes that a large proportion of the increase in deaths is due to illegally-made fentanyl; as the statistics on overdose deaths (as of 2015) do not distinguish pharmaceutical fentanyl from illegally-made fentanyl, the actual death rate could, therefore, be much higher than reported.[65]

Those taking fentanyl-laced heroin are more likely to overdose because they do not know they also are ingesting the more powerful drug. The most high-profile death involving an accidental overdose of fentanyl was singer Prince.[66][67][68]

Fentanyl has surpassed heroin as a killer in several locales: in all of 2014 the CDC identified 998 fatal fentanyl overdoses in Ohio, which is the same number of deaths recorded in just the first five months of 2015. The U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Ohio stated:

One of the truly terrifying things is the pills are pressed and dyed to look like oxycodone. If you are using oxycodone and take fentanyl not knowing it is fentanyl, that is an overdose waiting to happen. Each of those pills is a potential overdose death.[69]

In 2016, the medical news site STAT reported that while Mexican cartels are the main source of heroin smuggled into the U.S., Chinese suppliers provide both raw fentanyl and the machinery necessary for its production.[69] In British Columbia, police discovered a lab making 100,000 fentanyl pills each month, which they were shipping to Calgary, Alberta. 90 people in Calgary overdosed on the drug in 2015.[69] In Southern California, a home-operated drug lab with six pill presses was uncovered by federal agents; each machine was capable of producing thousands of pills an hour.[69]

Overdoses involving fentanyl have greatly contributed to the havoc caused by the opioid epidemic. In New Hampshire, two thirds of the fatal drug overdoses involved fentanyl, and most do not know that they are taking fentanyl. In 2017, a cluster of fentanyl overdoses in Florida was found to be caused by street sales of fentanyl pills sold as Xanax. According to the DEA, one kg of fentanyl can be bought in China for $3,000 to $5,000, and then smuggled into the United States by mail or Mexican drug cartels to generate over $1.5 million in revenue. The profitability of this drug has led dealers to adulterate other drugs with fentanyl without the knowledge of the drug user.[70]

Pill mills

A "pill mill" is a clinic that dispenses narcotics to patients without a legitimate medical purpose. This is done at clinics and doctors offices, where doctors examine patients extremely quickly with a purpose of prescribing painkillers. These clinics often charge an office fee of $200 to $400 and can see up to 60 patients a day, which is very profitable for the clinic.[71] Pill mills are also large suppliers of the illegal painkiller black markets on the streets.[72] Dealers may hire people to go to pill mills to get painkiller prescriptions.[73] There have been attempts to shut down pill mills, and 250 pill mills in Florida were shut down in 2015.[74] Florida clinics also are no longer allowed to dispense painkillers directly from their clinics, which has helped reduce the distribution of prescription opiates.[75] Since the implementation of pill mill laws and drug monitoring programs in Florida, high-risk patients (defined as those who use both benzodiazepines and opioids, those who have been using high opioid doses for extended periods of time, or "opioid shoppers" that obtain their opioid painkillers from multiple sources) have shown significant reductions in opioid use.[76]

Trafficking

As the number of opioid prescriptions rose, drug cartels began flooding the U.S. with heroin from Mexico. For many opioid users, heroin was cheaper, more potent, and often easier to acquire than prescription medications.[13] According to the CDC, tighter prescription policies by doctors did not necessarily lead to this increased heroin use.[77] The main suppliers of heroin to the U.S. have been Mexican transnational criminal organizations.[13] From 2005–2009, Mexican heroin production increased by over 600%, from an estimated 8 metric tons in 2005 to 50 metric tons in 2009.[13] Between 2010 and 2014, the amount seized at the border more than doubled.[78] According to the DEA, smugglers and distributors "profit primarily by putting drugs on the street and have become crucial to the Mexican cartels."[6]: 3

Illicit fentanyl is commonly made in Mexico and trafficked by cartels.[79] North America's dominant trafficking group is Mexico's Sinaloa Cartel, which has been linked to 80 percent of the fentanyl seized in New York.[18]

Causes

What the U.S. Surgeon General dubbed "The Opioid Crisis" likely began with over-prescription of powerful opioid pain relievers in the 1990s, which led to them becoming the most prescribed class of medications in the United States. Opioids initiated for post surgery or trauma pain management is one of the leading causes of opioid misuse, where approximately 4% to 8% of patients continued opioid use after trauma or surgery.[4] When people continue to use opioids beyond what a doctor prescribes, whether to minimize pain or induce euphoric feelings, it can mark the beginning stages of an opiate addiction, with a tolerance developing and eventually leading to dependence, when a person relies on the drug to prevent withdrawal symptoms.[64] Writers have pointed to a widespread desire among the public to find a pill for any problem, even if a better solution might be a lifestyle change, such as exercise, improved diet, and stress reduction.[80][81][82]

In the late 1990s, around 100 million people or a third of the U.S. population were estimated to be affected by chronic pain. This led to a push by drug companies and the federal government to expand the use of painkilling opioids.[15] In addition to this, organizations like the Joint Commission began to push for more attentive physician response to patient pain, referring to pain as the fifth vital sign. This exacerbated the already increasing number of opioids being prescribed by doctors to patients.[83] Between 1991 and 2011, painkiller prescriptions in the U.S. tripled from 76 million to 219 million per year, and as of 2016 more than 289 million prescriptions were written for opioid drugs per year.[84]: 43 Mirroring the positive trend in the volume of opioid pain relievers prescribed is an increase in the admissions for substance abuse treatments and increase in opioid-related deaths. This illustrates how legitimate clinical prescriptions of pain relievers are being diverted through an illegitimate market, leading to misuse, addiction, and death.[85] With the increase in volume, the potency of opioids also increased. By 2002, one in six drug users were being prescribed drugs more powerful than morphine; by 2012, the ratio had doubled to one-in-three.[15] The most commonly prescribed opioids have been oxycodone (OxyContin and Percocet) and hydrocodone (Vicodin).

The epidemic has been described as a "uniquely American problem".[86][87] The structure of the US healthcare system, in which people not qualifying for government programs are required to obtain private insurance, favors prescribing drugs over expensive therapies. According to Professor Judith Feinberg from the West Virginia University School of Medicine, "Most insurance, especially for poor people, won't pay for anything but a pill."[88] Prescription rates for opioids in the US are 40 percent higher than the rate in other developed countries such as Germany or Canada.[89] Josef Stehlik, medical director of the Heart Transplant Program at the University of Utah elaborated: "Opioids are treated differently here. First, there’s much less prescription of opioids for pain in Europe, so there’s less chance of addiction from people who started opioid use in a legal, medical way. Second, in many but not all European countries, the rate of illicit opioid use is either stagnant or decreasing."[87] While the rates of opioid prescriptions increased between 2001 and 2010, the prescription of non-opioid pain relievers (aspirin, ibuprofen, etc.) decreased from 38% to 29% of ambulatory visits in the same time period,[90] and there has been no change in the amount of pain reported in the U.S.[91][84] This has led to differing medical opinions, with some noting that there is little evidence that opioids are effective for chronic pain not caused by cancer.[77]

Several studies have been conducted to find out how opioids were primarily acquired, with varying findings. A 2013 national survey indicated that 74% of opioid abusers acquired their opioids directly from a single doctor, friend, or relative, who in turn received their opioids from a clinician.[86] Though aggressive opioid prescription practices played the biggest role in creating the epidemic, the popularity of illegal substances such as potent heroin and illicit fentanyl have become an increasingly large factor. It has been suggested that decreased supply of prescription opioids caused by reforms turned people who were already addicted to opioids towards illegal substances.[92] By 2015, approximately 50% of drug overdoses were not the result of an opioid product from a prescription, though most abusers' first exposure had still been by lawful prescription.[86] By 2018, another study suggested that 75% of opioid abusers started their opioid use by taking drugs which had been obtained in a way other than by legitimate prescription.[93]

-

The top line represents the yearly number of benzodiazepine deaths that involved opioids in the US. The bottom line represents benzodiazepine deaths that did not involve opioids.[2]

-

Opioid involvement in cocaine overdose deaths. The yellow line (the top line in later years) represents the number of yearly cocaine deaths that also involved opioids.[2]

Effects

Effects of the opioid epidemic are multifactorial. The high death rate by overdose, the spread of communicable diseases, and the economic burden are major issues caused by the epidemic.

The opioid epidemic has since emerged as one of the worst drug crises in American history: more than 33,000 people died from overdoses in 2015, nearly equal to the number of deaths from car crashes, with deaths from heroin alone more than from gun homicides.[95] It has also left thousands of children suddenly in need of foster care after their parents have died from an overdose.[96]

In Alberta, a 2017 report stated that emergency department visits as a result of opiate overdose rose 1,000% in the five years prior.[17]

In 2016, a study estimated that the cost of prescription opioid overdoses, abuse and dependence in the United States in 2013 was approximately $78.5 billion, most of which was attributed to health care and criminal justice spending, along with lost productivity. However, in two years, statistics show significantly larger estimates because the epidemic has worsened with overdose and with deaths doubling in the past decade. The White House stated on November 20, 2017, that in 2015 alone the opioid epidemic cost the United States an estimated $504 billion.[97]

The University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, lost two employees after both died in a murder-suicide over the refusal of Dr. Todd Graham, 56 to renew the opioid prescription for the wife of Mike Jarvis, 48.[98] United States Representative Jackie Walorski sponsored a bill in the memory of the doctor that would not overprescribe. ( The Dr. Todd Graham Pain Management Improvement Act ) in the United States House of Representatives to address the opioid epidemic.[99]

Demographics

6.9–11 11.1–13.5 13.6–16.0 16.1–18.5 18.6–21.0 21.1–52.0 |

In the U.S., addiction and overdose victims are mostly Native American and working-class.[13] Native Americans and Alaska Natives experienced a five-fold increase in opioid-overdose deaths between 1999 and 2015, with Native Americans having the highest increase of any demographic group.[101] One physician conjectured that this trend may be due to doctors being less likely to prescribe opiates to patients because of past drug abuse stereotypes.[102]

In the United States, those living in rural areas of the country have been the hardest hit since the Great Depression of 2k as a percentage of the national population,[103] Canada is similarly affected, with 90% of cities with the highest hospitalization rates having a population below 225,000.[104] Western Canada has an overdose rate nearly 10 times that of the eastern provinces.[105]

Prescription drugs abusers have been increasing in teenagers with access to parents medicine cabinets, especially as 12- to 17-year-old abused girls were one-third of all new abusers of prescription drugs in 2006. Teens abuse prescription drugs more than any illicit drug except marijuana, more than cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine combined, per the Office of National Drug Control Policy's 2008 report Prescription for Danger.[citation needed] Deaths from overdose of heroin affect a younger demographic than deaths from other opiates.[13] The Canadian Institute for Health Information found that while overall a third of overdoses were intentional, among those ages 15–24 nearly half were intentional.[17]

Prescription rates for opioids vary widely across the states. In 2012, healthcare providers in the highest-prescribing state wrote almost three times as many opioid prescriptions per person as those in the lowest-prescribing state. Health issues that cause people pain do not vary much from place to place and do not explain this variability in prescribing.[106] In Hawaii, doctors wrote about 52 prescriptions for every 100 people, whereas in Alabama, they wrote almost 143 prescriptions per 100 people. Researchers suspect that the variation results from a lack of consensus among elected officials in different states about how much pain medication to prescribe. A higher rate of prescription drug use does not lead to better health outcomes or patient satisfaction, according to studies.[13]

A study argues that from 2000 to 2012, the use of substances, such as cocaine/crack, marijuana/hashish, heroin, and non-prescription methadone, and other drugs, is becoming more prevalent among people age 95 and older from a variety of backgrounds. The results of this study show an increase in use for older adults in these demographics “African Americans (21% to 28%), females (20% to 24%), high school teens (63% to 75%), transgenders (15% to 19%), under-employed (77% to 84%), and the wealthy with psychiatric problems (17% to 32%).” This is useful to the research paper by supporting through scientific data that this epidemic is on the rise due to social, psychological, and physiological issues being a key factor in the racialization of drug users.[107]

In Palm Beach County, Florida, overdose deaths went from 149 in 2012 to 588 in 2016.[108] In Middletown, Ohio, overdose deaths quadrupled in the 15 years since 2000.[109] In British Columbia, 967 people died of an opiate overdose in 2016, and the Canadian Medical Association expected over 1,500 deaths in 2017.[110] In Pennsylvania, the number of opioid deaths increased 44 percent from 2016 to 2017, with 5,200 deaths in 2017. Governor Tom Wolf declared a state of emergency in response to the crisis.[111]

| Table: Opioid prescriptions per 100 persons in 2012.[112] | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | Opioid prescriptions written | Rank |

| Alabama | 142.9 | 1 |

| Alaska | 65.1 | 46 |

| Arizona | 82.4 | 26 |

| Arkansas | 115.8 | 8 |

| California | 57 | 50 |

| Colorado | 71.2 | 40 |

| Connecticut | 72.4 | 38 |

| Delaware | 90.8 | 17 |

| District of Columbia | 85.7 | 23 |

| Florida | 72.7 | 37 |

| Georgia | 90.7 | 18 |

| Hawaii | 52 | 51 |

| Idaho | 85.6 | 24 |

| Illinois | 67.9 | 43 |

| Indiana | 109.1 | 9 |

| Iowa | 72.8 | 36 |

| Kansas | 93.8 | 16 |

| Kentucky | 128.4 | 4 |

| Louisiana | 118 | 7 |

| Maine | 85.1 | 25 |

| Maryland | 74.3 | 33 |

| Massachusetts | 70.8 | 41 |

| Michigan | 107 | 10 |

| Minnesota | 61.6 | 48 |

| Mississippi | 120.3 | 6 |

| Missouri | 94.8 | 14 |

| Montana | 82 | 27 |

| Nebraska | 79.4 | 28 |

| Nevada | 94.1 | 15 |

| New Hampshire | 71.7 | 39 |

| New Jersey | 62.9 | 47 |

| New Mexico | 73.8 | 35 |

| New York | 59.5 | 49 |

| North Carolina | 96.6 | 13 |

| North Dakota | 74.7 | 32 |

| Ohio | 100.1 | 12 |

| Oklahoma | 127.8 | 5 |

| Oregon | 89.2 | 20 |

| Pennsylvania | 88.2 | 21 |

| Rhode Island | 89.6 | 19 |

| South Carolina | 101.8 | 11 |

| South Dakota | 66.5 | 45 |

| Tennessee | 142.8 | 2 |

| Texas | 74.3 | 34 |

| Utah | 85.8 | 22 |

| Vermont | 67.4 | 44 |

| Virginia | 77.5 | 29 |

| Washington (state) | 77.3 | 30 |

| West Virginia | 137.6 | 3 |

| Wisconsin | 76.1 | 31 |

| Wyoming | 69.6 | 42 |

Outside North America

Approximately 80 percent of the global pharmaceutical opioid supply is consumed in the United States.[113] It has also become a serious problem outside the U.S., mostly among young adults.[114] The concern not only relates to the drugs themselves, but to the fact that in many countries doctors are less trained about drug addiction, both about its causes or treatment.[91] According to an epidemiologist at Columbia University: "Once pharmaceuticals start targeting other countries and make people feel like opioids are safe, we might see a spike [in opioid abuse]. It worked here. Why wouldn't it work elsewhere?" [91]

The majority of deaths worldwide from overdoses were from either medically prescribed opioids or illegal heroin. In Europe, prescription opioids accounted for three-quarters of overdose deaths among those between ages 15 and 39.[114] Some worry that the epidemic could become a worldwide pandemic if not curtailed.[91] Prescription drug abuse among teenagers in Canada , Australia , and Europe were at rates comparable to U.S. teenagers.[91] In Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, and in parts of China , surveys found that one in ten students had used prescription painkillers for non-medical purposes. Similar high rates of non-medical use were found among the young throughout Europe, including Spain and the United Kingdom .[91]

From January to August 2017, there were 60 fatal overdoses of fentanyl in the UK.[115]

The worry surrounding the potential of a worldwide pandemic has affected the disparity in opioid accessibility in countries around the world. Approximately 25.5 million people per year, including 2.5 million children, die without pain relief worldwide, with many of these cases occurring in low and middle-income countries. The current disparity in accessibility to pain relief in various countries is significant; the U.S. produces or imports 30 times as much pain relief medication as it needs while low-income countries such as Nigeria receive less than 0.2% of what they need, and 90% of all the morphine in the world is used by the world's richest 10%.[116] America's opioid epidemic has resulted in an “opiophobia” that is stirring conversations among some Western legislators and philanthropists about adopting a “war on drugs rhetoric” to oppose the idea of increasing opioid accessibility in other countries, in fear of starting similar opioid epidemics abroad.[117] The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), a monitoring agency established by the U.N. to prevent addiction and ensure appropriate opioid availability for medical use, has written model laws limiting opioid accessibility that it encourages countries to enact. Many of these laws more significantly impact low-income countries; for instance, one model law ruled that only doctors could supply opioids, which limited opioid accessibility in poorer countries that had a scarce number of doctors.[118]

In 2018, deputy head of China's National Narcotics Commission Liu Yuejin criticized the U.S. market's role in driving opioid demand.[119]

Countermeasures

U.S. federal government

In 2010, the US government began cracking down on pharmacists and doctors who were over-prescribing opioid painkillers. An unintended consequence of this was that those addicted to prescription opiates turned to heroin, a significantly more potent but cheaper opioid, as a substitute.[15][21] A 2017 survey in Utah of heroin users found about 80 percent started with prescription drugs.[120]

In 2010, the Controlled Substances Act was amended with the Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act, which allows pharmacies to accept controlled substances from households or long-term care facilities in their drug disposal programs or "take-back" programs.[121]

In 2011, the federal government released a white paper describing the administration's plan to deal with the crisis. Its concerns have been echoed by numerous medical and government advisory groups around the world.[122][123][124] In July 2016, President Barack Obama signed into law the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which expands opioid addiction treatment with buprenorphine and authorizes millions of dollars in funding for opioid research and treatment.[125]

In 2016, the U.S. Surgeon General listed statistics which describe the extent of the problem.[84] The House and Senate passed the Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act which was signed into law by President Obama on April 19, 2016, and may have decreased the DEA's ability to intervene in the opioid crisis.[126] In December 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act, which includes $1 billion in state grants to fight the opioid epidemic, was passed by Congress by a wide bipartisan majority (94-5 in the Senate, 392-26 in the House of Representatives),[127] and was signed into law by President Obama.[128]

As of March 2017, President Donald Trump appointed a commission on the epidemic, chaired by Governor Chris Christie of New Jersey.[129][130][131] On August 10, 2017, President Trump agreed with his commission's report released a few weeks earlier and declared the country's opioid crisis a "national emergency".[132][133] Trump nominated Representative Tom Marino to be director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, or "drug czar".[134] One interview with the director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, where he states that because opioid users are predominantly white and middle class, they “know how to call a legislator, [and] fight with their insurance company.”[135]

However, on October 17, 2017, Marino withdrew his nomination after it was reported that his relationship with the drug industry might be a conflict of interest.[136][137] In July 2017, FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb stated that for the first time, pharmacists, nurses, and physicians would have training made available on appropriate prescribing of opioid medicines, because opioid addiction had become the "FDA's biggest crisis".[26]

In April 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services announced their "Opioid Strategy" consisting of five aims:

- Improve access to prevention, treatment, and recovery support services to prevent the health, social, and economic consequences associated with opioid addiction and to enable individuals to achieve long-term recovery;

- Target the availability and distribution of overdose-reversing drugs to ensure the broad provision of these drugs to people likely to experience or respond to an overdose, with a particular focus on targeting high-risk populations;

- Strengthen public health data reporting and collection to improve the timeliness and specificity of data and to inform a real-time public health response as the epidemic evolves;

- Support cutting-edge research that advances our understanding of pain and addiction, leads to the development of new treatments, and identifies effective public health interventions to reduce opioid-related health harms; and

- Advance the practice of pain management to enable access to high-quality, evidence-based pain care that reduces the burden of pain for individuals, families, and society while also reducing the inappropriate use of opioids and opioid-related harms.[40]

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has taken another approach to this epidemic: requiring manufacturers of long-acting opioids to sponsor educational programs for prescribers. The FDA hoped that these educational programs would help deter off-label and over-prescribing; however, it is still unclear if these programs truly have a positive effect on reducing opioid prescriptions.[43]

In July 2017, a 400-page report by the National Academy of Sciences presented plans to reduce the addiction crisis, which it said was killing 91 people each day.[138]

SAMHSA administers the Opioid State Targeted Response grants, a two-year program authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act which provided $485 million to states and U.S. territories in the fiscal year 2017 for the purpose of preventing and combatting opioid misuse and addiction.[40]

State and local governments

In response to the surging opioid prescription rates by health care providers that contributed to the opioid epidemic, U.S. states began passing legislation to stifle high-risk prescribing practices (such as prescribing high doses of opioids or prescribing opioids long-term). These new laws fell primarily into 1 of the following 4 categories:

- Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) enrollment laws: prescribers must enroll in their state's PDMP, an electronic database containing a record of all patients' controlled substance prescriptions

- PDMP query laws: prescribers must check the PDMP before prescribing an opioid

- Opioid prescribing cap laws: opioid prescriptions cannot exceed designated doses or durations

- Pill mill laws: pain clinics are closely regulated and monitored to minimize the prescription of opioids non-medically[139]

In July 2016, governors from 45 U.S. states and three territories entered into a formal "Compact to Fight Opioid Addiction". They agreed that collective action would be needed to end the opioid crisis, and they would coordinate their responses across all levels of government and the private sector, including opioid manufacturers and doctors.[140]

In March 2017, several states issues responses to the opioid crisis. The governor of Maryland declared a state of emergency to combat the rapid increase in overdoses by increasing and speeding up coordination between the state and local jurisdictions.[141][22] In 2016, about 2,000 people in the state had died from opioid overdoses.[142] Delaware, which has the 12th-highest overdose death rate in the U.S., introduced bills to limit doctors' ability to over-prescribe painkillers and improve access to treatment. In 2015, 228 people had died from overdose, which increased 35%—to 308—in 2016.[143] A similar plan was created in Michigan, which introduced the Michigan Automated Prescription System (MAPS), allowing doctors to check when and what painkillers have already been prescribed to a patient, and thereby help keep addicts from switching doctors to receive drugs.[144][145] In Maine, new laws were imposed which capped the maximum daily strength of prescribed opioids and which limited prescriptions to seven days.[21] Studies have found that after the implementation of “pill mill laws” in Texas, opioid opioid dose, volume, prescriptions and pills dispensed within the state were all significantly reduced.[146]

During the 2017 general session of the Utah Legislature, Rep. Edward H. Redd and Sen. Todd Weiler proposed amendments to Utah's involuntary commitment statutes which would allow relatives to petition a court to mandate substance-abuse treatment for adults.[147][120]

In West Virginia, which leads the nation in overdose deaths per capita, lawsuits seek to declare drug distribution companies a "public nuisance" in an effort to place accountability upon the drug industry for the costs associated with the epidemic.[148][149] In February 2017, officials in Everett, Washington, filed a lawsuit against Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin, for negligence by allowing drugs to be illegally trafficked to residents and failing to prevent it. The city wants the company to pay the costs of handling the crisis.[150]

Arizona's Governor Doug Ducey signed the Arizona Opioid Epidemic Act on January 26, 2018, to confront the state's opioid crisis. In Maricopa County which includes Phoenix, 3,114 overdoses were reported from June 15, 2017, through January 11, 2018.[151] The law provides $10 million for treatment and limits an initial prescription to five days with exemptions.

On January 17, 2018, several senators, including New Hampshire Senator Maggie Hassan, wrote a letter to President Trump expressing extreme concern regarding his lack of commitment to the White House Office of Nation Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), which plays a critical role in coordinating the federal government's response to the fentanyl, heroin, and opioid epidemic. The letter states that the ONDCP and DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) have both been without permanent, Senate-confirmed leadership since Trump took office, and he has not presented the Senate with qualified candidates for these positions. The senators requested that Trump provide their offices with a list of his political appointees to key drug policy positions and those appointees' relevant qualifications, including appointees at ONDCP; the Department of Justice, including the DEA; the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); and elsewhere in his administration.

Avalere Health has researched recent individual state efforts to combat the opioid crisis by providing access to life-saving drugs typically associated with opioid overdoses. Their research measured how states are performing in providing a key frontline treatment for opioid addiction (Buprenorphine), compared to the amount of opioid overdose deaths they have by state. Generally, the more access a state can provided drug users to the drug, the lower the mortality rate amongst opioid addicts were in a given state.[152]

Prescription drug monitoring

In 2016, the CDC published its "Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain", recommending opioids only be used when benefits for pain and function are expected to outweigh risks, and then used at the lowest effective dosage, with avoidance of concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use whenever possible.[153] Silvia Martins, an epidemiologist at Columbia University, has suggested getting out more information about the risks:

The greater "social acceptance" for using these medications (versus illegal substances) and the misconception that they are "safe" may be contributing factors to their misuse. Hence, a major target for intervention is the general public, including parents and youth, who must be better informed about the negative consequences of sharing with others medications prescribed for their own ailments. Equally important is the improved training of medical practitioners and their staff to better recognize patients at potential risk of developing nonmedical use, and to consider potential alternative treatments as well as closely monitor the medications they dispense to these patients.[114]

As of April 2017, prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) exist in every state.[154] A person on opioids for more than three months has a 15-fold (1,500%) greater chance of becoming addicted.[77] PDMPs allow pharmacists and prescribers to access patients' prescription histories to identify suspicious use. However, a survey of US physicians published in 2015 found only 53% of doctors used these programs, while 22% were not aware these programs were available.[155] Following the implementation of pill mill laws and prescription drug monitoring programs in Florida, there was a large decline in opioid prescriptions written by high-risk prescribers (those prescribing the top 5th of opioids by volume).[76] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was tasked with establishing and publishing a new guideline, and was heavily lobbied.[156][157]

A 2018 study by the University of Florida concluded that there is little evidence that drug-monitoring databases are having a positive effect on the number of drug overdoses in the U.S.[158] Lead researching Chris Delcher, Ph.D., also concluded that "there was a concurrent rise in fatal overdoses from fentanyl, heroin and morphine" due to ease of availability and lower cost following prescription drug crackdowns.[158]

In the media

Media coverage has largely focused on law-enforcement solutions to the epidemic, which portray the issue as criminal, whereas some see it as a medical issue.[159] There has been differential reporting on how white suburban or rural addicts of opioids are portrayed compared to black and Hispanic urban addicts, often of heroin, reinforcing stereotypes of drug users and drug-using offenders.[160] In newspapers, white addicts' stories are often given more space, allowing for a longer backstory explaining how they became addicted, and what potential they had before using drugs.[160] In early 2016 the national desk of the Washington Post began an investigation with assistance from fired DEA regulator Joseph Razzazzisi on the rapidly increasing numbers of opioid related deaths.[161]

While media coverage has focused more heavily on overdoses among whites, use among African, Hispanic and Native Americans has increased at similar rates. Deaths by overdose among white, black, and Native Americans increased by 200–300% from 2010–2014. During this time period, overdoses among Hispanics increased 140%, and the data available on overdoses by Asians was not comprehensive enough to draw a conclusion.[13]

Social media may also be an outlet for detecting illegal online sales of opioids. In 2017, researchers tested a methodology that used keywords to aggregate tweets and employed unsupervised machine learning and web forensic analyses to identify illegal online marketing of opioids. These efforts can aid criminal investigators in identifying violators of the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act.[162]

Treatment

The opioid epidemic is often discussed in terms of prevention, but helping those who are already addicts is talked about less frequently.[159] Opioid dependence can lead to a number of consequences like contraction of HIV and overdose. For addicts who wish to treat their addiction, there are two classes of treatment options available: medical and behavioral.[163] Neither is guaranteed to successfully treat opioid addiction. Which, or which combination, is most effective varies from person to person.[164]

These treatments are doctor-prescribed and -regulated, but differ in their treatment mechanism. Popular treatments include kratom, naloxone, methadone, and buprenorphine, which are more effective when combined with a form of behavioral treatment.[164] The price of opioid treatment may vary due to different factors, but the cost of treatment can range from $6,000 to $15,000 a year. Which based off the research most addicts come from lagging economic environment which multiple addicts do not have the support or funding to complete alternative medication for the addictions.

Methadone

Methadone has been used for opioid dependence since 1964, and studied the most of the pharmacological treatment options.[165] It is a synthetic long-acting opioid, so it can replace multiple heroin uses by being taken once daily.[164] It works by binding to the opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord, activating them, reducing withdrawal symptoms and cravings while suppressing the "high" that other opioids can elicit. The decrease in withdrawal symptoms and cravings allow the user to slowly taper off the drug in a controlled manner, decreasing the likelihood of relapse. It is not accessible to all addicts. It is a regulated substance, and requires that each dose be picked up from a methadone clinic daily. This can be inconvenient as some patients are unable to travel to a clinic, or avoid the stigma associated with drug addiction.[164]

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is used similarly to methadone, with some doctors recommending it as the best solution for medication-assisted treatment to help people reduce or quit their use of heroin or other opiates. It is claimed to be safer and less regulated than methadone, with month-long prescriptions allowed. It is also said to eliminate opiate withdrawal symptoms and cravings in many patients without inducing euphoria.[166] Probuphine is an implantable form of buprenorphine lasting six months.[167] Rates of buprenorphine use increased between 2003 and 2011, with sales increasing, on average, by 40%.[168]

Unlike methadone treatment, which must be performed in a highly structured clinic, buprenorphine, according to SAMHSA, can be prescribed or dispensed in physician offices.[169] Patients can thereby receive a full year of treatment for a fraction of the cost of detox programs.[166]

Behavioral treatment

It is less effective to use behavioral treatment without medical treatment during initial detoxification. It has similarly been shown that medical treatments tend to get better results when accompanied by behavioral treatment.[163] Popular behavioral treatment options include group or individual therapy, residential treatment centers, and twelve-step programs such as Narcotics Anonymous.[165]

Harm Reduction Approaches

Harm reduction programs operate under the understanding that certain levels of drug use are inevitable and focus on minimizing adverse effects associated with drug use rather than stopping the behavior itself. In the context of the opioid epidemic, harm reduction strategies are designed to improve health outcomes and reduce overdose deaths.[43]

Naloxone

Naloxone (most commonly sold under the brand name Narcan) can be used as a rescue medication for opioid overdose or as a preventive measure for those wanting to stop using opiates. It is an opioid antagonist, meaning it binds to opioid receptors, which prevents them from being activated by opiates. It binds more strongly than other drugs, so that when someone is overdosing on opioids, naloxone can be administered, allowing it to take the place of the opioid drug in the person's receptors, turning them off. This blocks the effect of the receptors.[164]

Many states have made Narcan available for purchase without a prescription. Additionally, peace officers in many districts have begun carrying Narcan on a routine basis.

Take-home naloxone overdose prevention kits have shown promise in areas exhibiting rapid increases in opioid overdoses and deaths due to the increased availability of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. Early implementation of programs that widely distribute THN kits across these areas can substantially reduce the number of opioid overdose deaths.[170] Additionally, persons at risk for opioid overdose did not engage in riskier, compensatory drug use as a result of having access to naloxone kits.[171]

Vivitrol is a long-lasting injectable form of naloxone that blocks the effects of opiates for four weeks. This eliminates the need to remember to take Narcan on a daily basis.[167] Naloxone is sometimes administered with other drugs such as buprenorphine, as a way to taper off buprenorphine over time.[164]

Safe injection sites

North America's first "safe injection site" opened in Vancouver . Rather than try to treat to prevent people from using drugs, these sites are intended to allow addicts to use drugs in an environment where help is immediately available in the event of an overdose. Health Canada has licensed 16 safe injection sites in the country.[172] In Canada, about half of overdoses resulting in hospitalization were accidental, while a third were deliberate overdoses.[17]

Despite the illegality of injecting illicit drugs in most places around the world, many injectable drug users report willingness to utilize safe injection sites. Of these willing injectable drug users, those at especially high risk for opioid overdose were significantly more likely to be willing to use a safe injection site. This observed willingness suggests that safe injection sites would be well utilized by the very individuals who could benefit most from them.[173]

Needle Exchange Programs (NEP)

The CDC defines needle exchange programs (NEP), also known as syringe services programs, as “community-based programs that provide access to sterile needles and syringes free of cost and facilitate safe disposal of used needles and syringes”[174] NEP were first established in the U.S. in the late 1980s as a response to the HIV pandemic. Because federal funding has long been banned from being used for NEP, their prominence in the U.S. has been minimal.[175] However, in early 2016, in the face of the ever-increasing heroin crisis, Congress effectively rolled back those regulations and is now allowing federal funding to support certain aspects of NEP.[174] NEP are cited by the CDC as a vital aspect of the multi-faceted approach to the opioid crisis.[176]

While opposition to NEP includes fears of increased drug use, studies have shown that they do not increase drug use among users or within a community.[177] NEP have also been known to increase admittance into addiction treatment centers, offer counseling, housing support and help users begin the path to recovery through outreach from trusted staff.[175] In addition, NEP that operate on a one-for-one basis help to drastically reduce the amount of discarded needles in public. Both the Center for Disease Control and National Institute of Health support the idea that NEP are a crucial aspect to a comprehensive approach to the opioid crisis.[178][174]

Use of blue lights in public spaces

As of 2018, some retailers have begun experimenting with the use of blue light bulbs in bathrooms in order to deter addicts from using such spaces to inject opiates.[179] Blue lights are said to make finding veins to inject more difficult.[179]

See also

- List of deaths from drug overdose and intoxication

- History of opium in China

- Global Commission on Drug Policy

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Opioid Data Analysis and Resources. Drug Overdose. CDC Injury Center. Click on "Rising Rates" tab for chart. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNIDA-deaths - ↑ 3.0 3.1 "WISQARS Fatal Injury Reports". https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Mohamadi, Amin; Chan, Jimmy J.; Lian, Jayson; Wright, Casey L.; Marin, Arden M.; Rodriguez, Edward K.; von Keudell, Arvind; Nazarian, Ara (August 1, 2018). "Risk Factors and Pooled Rate of Prolonged Opioid Use Following Trauma or Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-(Regression) Analysis". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume 100 (15): 1332–1340. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.01239. ISSN 1535-1386. PMID 30063596.

- ↑ "Information sheet on opioid overdose". World Health Organization. November 2014. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/information-sheet/en/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "2015 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary" , DEA, Oct. 2015

- ↑ "Vital Signs: Overdoses of Prescription Opioid Pain Relievers – United States, 1999–2008" (in en). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm?s_cid=mm6043a4_w.

- ↑ "Drug overdoses now kill more Americans than guns", CBS News, December 9, 2016

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Katz, Josh (June 5, 2017). "Drug Deaths in America Are Rising Faster Than Ever". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/06/05/upshot/opioid-epidemic-drug-overdose-deaths-are-rising-faster-than-ever.html.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bernstein, Lenny; Ingraham, Christopher (December 21, 2017). "Fueled by drug crisis, U.S. life expectancy declines for a second straight year" (in en-US). Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/fueled-by-drug-crisis-us-life-expectancy-declines-for-a-second-straight-year/2017/12/20/2e3f8dea-e596-11e7-ab50-621fe0588340_story.html.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 National Center for Health Statistics. "Provisional Counts of Drug Overdose Deaths, as of 8/6/2017" (PDF). United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/monthly-drug-overdose-death-estimates.pdf. Source lists US totals for 2015 and 2016 and statistics by state.

- ↑ Lopez, German (July 7, 2017). "In 2016, drug overdoses likely killed more Americans than the entire wars in Vietnam and Iraq". Vox (Vox Media). https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/7/7/15925488/opioid-epidemic-deaths-2016.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Nolan, Dan; Amico, Chris (February 23, 2016). "How Bad is the Opioid Epidemic?". PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/how-bad-is-the-opioid-epidemic/.

- ↑ "America's Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescription Drug Abuse", National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), May 14, 2014

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 "America’s opioid epidemic is worsening", the Economist (U.K.) March 6, 2017,

- ↑ "STAT forecast: Opioids could kill nearly 500,000 Americans in the next decade", STAT, June 27, 2017,

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 "Canada's opioid crisis is burdening the health care system, report warns". 2017-09-14. https://globalnews.ca/news/3743705/canadas-opioid-crisis-is-burdening-the-health-care-system-report-warns/. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Miroff, Nick (November 13, 2017). "Mexican traffickers making New York a hub for lucrative — and deadly — fentanyl". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/at-the-new-york-division-of-fentanyl-inc-a-banner-year/2017/11/13/c3cce108-be83-11e7-af84-d3e2ee4b2af1_story.html. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ↑ "White House: True cost of opioid epidemic tops $500 billion". 2017-11-20. https://www.statnews.com/2017/11/20/white-house-opioid-epidemic/.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "CDC Chief Frieden: How to end America's growing opioid epidemic", Fox News, December 17, 2016

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 Caldwell, Christoper. "American Carnage: The New Landscape of Opioid Addiction", First Things, April 2017

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Turque, B. Maryland governor declares state of emergency for opioid crisis, The Washington Post (March 1, 2017).

- ↑ Katharine Q. Seelye, In Annual Speech, Vermont Governor Shifts Focus to Drug Abuse Image, New York Times (January 9, 2014).

- ↑ Mark Hofmann, Lawmakers react to governor's opioid state of emergency, Herald Standard (January 12, 2018).

- ↑ German Lopez, I looked for a state that’s taken the opioid epidemic seriously. I found Vermont., Vox (October 32, 2017).

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "FDA's Scott Gottlieb: Opioid addiction is FDA's biggest crisis now", CNBC, July 21, 2017

- ↑ "Trump declares opioids a public health emergency but pledges no new money", Chicago Tribune, October 26, 2017

- ↑ "President Trump delivers speech on opioid crisis", PBS, October 26, 2017

- ↑ "Integrating & Expanding Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Data". 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pehriie_report-a.pdf.

- ↑ Wang, Lucy Xiaolu (February 15, 2018) (in en). The Complementarity of Health Information and Health IT for Reducing Opioid-Related Mortality and Morbidity. Rochester, NY. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3176809.

- ↑ "Opioid epidemic shares chilling similarities with the past" , Chron, October 30, 2017

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "The devastating effect of opioids on our society". 2016-08-26. http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/healthcare/293473-the-devastating-effect-of-opioids-on-our-society.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Moghe, Sonia. "Opioids: From 'wonder drug' to abuse epidemic". http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/12/health/opioid-addiction-history/. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ↑ WGBH educational foundation. Interview with Dr. Robert DuPont. PBS.org (February 18, 1970)

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 "Opioid crisis: The letter that started it all". BBC News (BBC). June 3, 2017. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-40136881. Retrieved June 3, 2017.

- ↑ Porter, J; Jick, H (1980). "Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics". New England Journal of Medicine 302 (2): 123. doi:10.1056/NEJM198001103020221. PMID 7350425.

- ↑ Leung, Pamela T.M; MacDonald, Erin M; Stanbrook, Matthew B; Dhalla, Irfan A; Juurlink, David N (2017). "A 1980 Letter on the Risk of Opioid Addiction". New England Journal of Medicine 376 (22): 2194–2195. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1700150. PMID 28564561.

- ↑ Scott, Peter Dale; Marshall, Jonathan. Cocaine Politics: Drugs, Armies, and the CIA in Central America, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (1991) p. 2

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Van Zee, Art (February 2009). "The promotion and marketing of OxyContin: commercial triumph, public health tragedy". American Journal of Public Health 99 (2): 221–7. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.131714. PMID 18799767.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Abuse, National Institute on Drug (October 25, 2017). "Federal Efforts to Combat the Opioid Crisis: A Status Update on CARA and Other Initiatives". https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2017/federal-efforts-to-combat-opioid-crisis-status-update-cara-other-initiatives. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Dowell, Deborah; Noonan, Rita K.; Houry, Debra (December 19, 2017). "Underlying factors in drug overdose deaths". JAMA 318 (23): 2295–2296. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.15971. PMID 29049472.

- ↑ Abuse, National Institute on Drug (June 1, 2017). "Opioid Overdose Crisis". https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 "The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction". Annu Rev Public Health 36: 559–74. March 2015. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122957. PMID 25581144.

- ↑ Frakt, Austin (2018-03-05). "Overshadowed by the Opioid Crisis: A Comeback by Cocaine". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/05/upshot/overshadowed-by-the-opioid-crisis-a-comeback-by-cocaine.html.

- ↑ Anderson, Leigh (May 18, 2014). "Heroin: Effects, Addictions & Treatment Options". https://www.drugs.com/illicit/heroin.html.

- ↑ Abuse, National Institute on Drug (January 27, 2016). "What Science tells us About Opioid Abuse and Addiction". https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/what-science-tells-us-about-opioid-abuse-addiction#references. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ Now a counselor, she went from stoned to straight, San Francisco Chronicle, November 2. 2015.

- ↑ Coplan, Paul (2012). "Findings from Purdue's Post-Marketing Epidemiology Studies of Reformulated OxyContin's Effects". NASCSA 2012 Conference. Scottsdale, Arizona. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130614115419/http://www.nascsa.org/Conference2012/Presentations/Coplan.pdf.

- ↑ Meier, Barry (May 10, 2007). "In Guilty Plea, OxyContin Maker to Pay $600 Million". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/10/business/11drug-web.html.

- ↑ "Impact of Abuse-Deterrent OxyContin on Prescription Opioid Utilization". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 24 (2): 197–204. 2015. doi:10.1002/pds.3723. PMID 25393216.

- ↑ Morin, Kristen A.; Eibl, Joseph K.; Franklyn, Alexandra M.; Marsh, David C. (2017). "The opioid crisis: Past, present and future policy climate in Ontario, Canada". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 12 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/s13011-017-0130-5. PMID 29096653.g

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the. "Press Announcements – FDA requests removal of Opana ER for risks related to abuse". https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm562401.htm. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Fentanyl Takes a Deadly Toll on Vermont", VTDigger, June 4, 2017

- ↑ "Why fentanyl is deadlier than heroin, in a single photo", Stat, September 29, 2016

- ↑ "Fentanyl drug profile", The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA)

- ↑ "CDC – Fentanyl: Workers at Risk – NIOSH Workplace Safety & Health Topics". August 30, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/fentanyl/risk.html. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ "Online Sales of Illegal Opioids from China Surge in U.S.", New York Times, January 24, 2018

- ↑ "Americans spent nearly $800M in 2 years on illegal fentanyl from China: 5 things to know", Becker's Hospital Review, January 25, 2018

- ↑ "Deadly synthetic opioids coming to US via 'dark web' and the postal service", Becker's Hospital Review, December 28, 2016

- ↑ "In China, Illegal Drugs Are Sold Online in an Unbridled Market", New York Times, June 21, 2015

- ↑ "China ‘stands ready to work with US’ to crack down on opioid dealers using postal service to smuggle drugs", South China Morning Post, January 25, 2018

- ↑ Katz, Josh (September 2, 2017). "The First Count of Fentanyl Deaths in 2016: Up 540% in Three Years" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/02/upshot/fentanyl-drug-overdose-deaths.html.

- ↑ "Orlando man pleads guilty to selling heroin mixed with fentanyl", Orlando.com, March 20, 2017

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "Why opioid overdose deaths seem to happen in spurts", CNN, February 8, 2017

- ↑ "Opioid Data Analysis", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), date?

- ↑ "Prince's Autopsy Result Highlights Dangers of Opioid Painkiller Fentanyl", ABC News, June 2, 2016

- ↑ "Documents highlight Prince’s struggle with opioid addiction", Seattle Times, April 17, 2017

- ↑ "Coroner: Franklin County fentanyl deaths hit 'unprecedented' rate of one per day", The Columbus Dispatch, March 16, 2017

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 "'Truly terrifying': Chinese suppliers flood US and Canada with deadly fentanyl", STAT, April 5, 2016,

- ↑ "Addressing America's Fentanyl Crisis". National Institute of Drug Abuse. April 6, 2017. https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/noras-blog/2017/04/addressing-americas-fentanyl-crisis.

- ↑ "Signs of a Pill Mill in Your Community". Kentucky Law Enforcement. https://docjt.ky.gov/Magazines/Issue%2041/files/assets/downloads/page0019.pdf.

- ↑ "Dr. Procter's House -". October 3, 2016. http://samquinones.com/reporters-blog/2016/10/03/dr-procters-house/. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ↑ Quinones, Sam (2015). Dreamland.

- ↑ "America's Pill Mills" (in en-US). DrugAbuse.com. July 1, 2016. https://drugabuse.com/featured/americas-pill-mills/.

- ↑ "Cracking Down on 'Pill Mill' Doctors" (in en). 2016-05-19. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/pill-mill-doctors-prosecuted-amid-opioid-epidemic#6.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Chang, Hsien-Yen; Murimi, Irene; Faul, Mark; Rutkow, Lainie; Alexander, G. Caleb (April 2018). "Impact of Florida's prescription drug monitoring program and pill mill law on high-risk patients: A comparative interrupted time series analysis". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 27 (4): 422–429. doi:10.1002/pds.4404. ISSN 1099-1557. PMID 29488663.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 "Opioid Prescriptions Fall After 2010 Peak, C.D.C. Report Finds", New York Times, July 6, 2017

- ↑ "Heroin Production in Mexico and U.S. Policy", Congressional Research Service report, March 3, 2016

- ↑ Achenbach, Joel (October 24, 2017). "Wave of addiction linked to fentanyl worsens as drugs, distribution, evolve". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/wave-of-addiction-linked-to-fentanyl-worsens-as-drugs-distribution-evolve/2017/10/24/5bedbcf0-9c97-11e7-8ea1-ed975285475e_story.html. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Too many meds? America's love affair with prescription medication". https://www.consumerreports.org/prescription-drugs/too-many-meds-americas-love-affair-with-prescription-medication/.

- ↑ "Pills for everything: The power of American pharmacy". https://curiousmatic.com/pills-for-everything-the-power-of-american-pharmacy/.

- ↑ Bekiempis, Victoria (2012-04-09). "America's prescription drug addiction suggests a sick nation". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/apr/09/america-prescription-drug-addiction.

- ↑ https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/Pain_Std_History_Web_Version_05122017.pdf

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 "Facing Addiction in America" , U.S. Surgeon General (2016), 413 pp

- ↑ "Rethinking opioid prescribing to protect patient safety and public health". JAMA 308 (18): 1865–6. November 2012. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14282. PMID 23150006.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 Shipton, Edward A.; Shipton, Elspeth I.; Shipton, Ashleigh J. (April 6, 2018). "A Review of the Opioid Epidemic: What Do We Do About It?". Pain and Therapy 7 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1007/s40122-018-0096-7. PMID 29623667.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 The U.S. Opioid Crisis Is So Devastating, It's Made More Organs Available for Transplant, Gizmodo

- ↑ Amos, Owen (October 25, 2017). "Why opioids are such an American problem" (in en-GB). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-41701718.

- ↑ Erickson, Amanda (December 28, 2017). "Analysis | Opioid abuse in the U.S. is so bad it's lowering life expectancy. Why hasn't the epidemic hit other countries?" (in en-US). Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/12/28/opioid-abuse-in-america-is-so-bad-its-lowering-our-life-expectancy-why-hasnt-the-epidemic-hit-other-countries/.

- ↑ "Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000–2010". Med Care 51 (10): 870–8. October 2013. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a95d86. PMID 24025657.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 91.2 91.3 91.4 91.5 "The opioid epidemic could turn into a pandemic if we're not careful", Washington Post, February 9, 2017

- ↑ Opioid Crisis: What People Don't Know About Heroin, Rolling Stone

- ↑ Pergolizzi Jr., J.V.; LeQuang, J.A.; Taylor Jr., R.; Raffa, R.B. (January 2018). "Going beyond prescription pain relievers to understand the opioid epidemic: the role of illicit fentanyl, new psychoactive substances, and street heroin". Postgrad Med. 130 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/00325481.2018.1407618. PMID 29190175.

- ↑ Fentanyl. Image 4 of 17. US DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration).

- ↑ "Heroin deaths surpass gun homicides for the first time, CDC data shows", Washington Post, December 8, 2016, Retrieved May 8, 2017

- ↑ "The Children of the Opioid Crisis", Wall Street Journal, December 15, 2016

- ↑ "The true cost of opioid epidemic tops $500 billion, White House says". 2017-11-20. https://www.cnbc.com/2017/11/20/the-true-cost-of-opioid-epidemic-tops-500-billion-white-house-says.html.

- ↑ Phillips, Kristine (July 29, 2018). "A doctor was killed for refusing to prescribe opioids, authorities say". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2017/07/29/a-doctor-was-killed-for-refusing-to-prescribe-opioids-authorities-say/?noredirect=on.

- ↑ "U.S. House passes bill named for slain South Bend doctor to address opioid epidemic". South Bend Tribune. June 20, 2018. https://www.southbendtribune.com/news/politics/u-s-house-passes-bill-named-for-slain-south-bend/article_7af3ac46-ba84-54dd-a278-36b7f1fbeb37.html.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Drug Overdose Death Data. CDC Injury Center. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The numbers for each state are in the data table below the map.

- ↑ "Native American Overdose Deaths Surge Since Opioid Epidemic". Drug Discovery & Development. Associated Press. March 15, 2018. https://www.dddmag.com/news/2018/03/native-american-overdose-deaths-surge-opioid-epidemic.

- ↑ Kolata, Gina; Cohen, Sarah (November 10, 2017). "Drug Overdoses Propel Rise in Mortality Rates of Young Whites". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/17/science/drug-overdoses-propel-rise-in-mortality-rates-of-young-whites.html. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ Sullivan, Andrew (March 16, 2017). "The Opioid Epidemic Is This Generation’s Pandemic Crisis". New York Magazine. http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2017/03/the-opioid-epidemic-is-this-generations-aids-crisis.html. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Canada opioid crisis hits small cities hardest". BBC News. September 14, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-41273792. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ↑ "National report: apparent opioid-related deaths (2016)". 2017-06-06. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-abuse/prescription-drug-abuse/opioids/national-report-apparent-opioid-related-deaths.html#def. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ "Prescription Opioid Data | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center". 2018-08-31. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/prescribing.html.

- ↑ Chhatre, Sumedha; Cook, Ratna; Mallik, Eshita; Jayadevappa, Ravishankar (August 22, 2017). "Trends in substance use admissions among older adults.". BMC Health Services Research 17 (1): 584. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2538-z. PMID 28830504.

- ↑ "Patient brokering exacerbates opioid crisis in Florida", South Bend Tribune, April 2, 2017

- ↑ de La Bruyere, Emily (August 2, 2017). "Middletown, Ohio, a city under siege: "Everyone I associate with abd including me, is on heroin"". Yahoo. https://www.yahoo.com/news/middletown-ohio-city-siege-everyone-know-heroin-155314072.html.

- ↑ "Doctors must help remedy opioid crisis in Canada, CMA meeting hears". http://www.cbc.ca/news/health/opioid-cma-1.4259178. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ Meyer, Katie; Sholtis, Brett (January 10, 2018). "Gov. Tom Wolf declares 'state of emergency' in Pa. opioid epidemic". WHYY. https://whyy.org/segments/video-gov-tom-wolf-declare-state-emergency-pa-opioid-epidemic/. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Vital Signs: Variation Among States in Prescribing of Opioid Pain Relievers and Benzodiazepines — United States, 2012", CDC, July 4, 2014

- ↑ "Americans consume vast majority of the world's opioids", Dina Gusovsky, CNBC, April 27, 2016

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 114.2 Martins, Silvia S; Ghandour, Lilian A (2017). "Nonmedical use of prescription drugs in adolescents and young adults: Not just a Western phenomenon". World Psychiatry 16 (1): 102–104. doi:10.1002/wps.20350. PMID 28127929.

- ↑ "Warnings after drug kills 'at least 60'". BBC News. August 1, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-40793887. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ↑ Knaul, Felicia Marie; Farmer, Paul E; Krakauer, Eric L; De Lima, Liliana; Bhadelia, Afsan; Jiang Kwete, Xiaoxiao; Arreola-Ornelas, Héctor; Gómez-Dantés, Octavio et al. (April 8, 2018). "Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report" (in English). The Lancet 391 (10128): 1391–1454. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 29032993. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)32513-8/fulltext.

- ↑ Jr, Donald G. McNeil (December 4, 2017). "‘Opiophobia’ Has Left Africa in Agony" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/04/health/opioids-africa-pain.html.

- ↑ US, The Conversation (March 25, 2016). "The Other Opioid Crisis – People in Poor Countries Can't Get the Pain Medication They Need" (in en-US). https://www.huffingtonpost.com/the-conversation-us/the-other-opioid-crisis_b_9548050.html.

- ↑ "China says United States domestic opioid market the crux of crisis". Reuters. June 25, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-drugs-usa/china-says-united-states-domestic-opioid-market-the-crux-of-crisis-idUSKBN1JL0D2.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 "Poll: Many Utahns know people who seek treatment for opioid addiction, but barriers remain", The Salt Lake Tribune, April 3, 2017

- ↑ Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 October 12, 2010, Government Publishing Office, 4 pp

- ↑ "Tackling the Opioid Public Health Crisis" , College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, September 8, 2010

- ↑ "First Do No Harm: Responding to Canada's Prescription Drug Crisis", Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, March 2013

- ↑ "UK: Task Force offers ideas for opioid addiction solutions". Delhidailynews.com. June 11, 2014. http://www.delhidailynews.com/news/UK--Task-Force-offers-ideas-for-opioid-addiction-solutions-1402491160/. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ↑ Summary of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, American Society of Addiction Medicine.

- ↑ Higham, Scott; Bernstein, Lenny (October 15, 2017). "How Congress allied with drug company lobbyists to derail the DEA’s war on opioids" (in en). The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2017/investigations/dea-drug-industry-congress/. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ↑ Mike DeBonis, Congress passes 21st Century Cures Act, boosting research and easing drug approvals, Washington Post (December 7, 2016).

- ↑ Juliet Eilperin & Carolyn Y. Johnson, paying tribute to Biden and bipartisanship, signs 21st Century Cures Act Tuesday, Washington Post (December 13, 2016).