Chemistry:Sodium decavanadate

| |

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Na6[V10O28] | |

| Molar mass | 1419.6 g/mol |

| Appearance | orange solid |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Sodium decavanadate describes any member of the family of inorganic compounds with the formula Na6[V10O28](H2O)n. These are sodium salts of the orange-colored decavanadate anion [V10O28]6−.[1] Numerous other decavanadate salts have been isolated and studied since 1956 when it was first characterized.[2]

Preparation

The preparation of decavanadate is achieved by acidifying an aqueous solution of ortho-vanadate:[1]

- 10 Na3[VO4] + 24 HOAc → Na6[V10O28] + 12 H2O + 24 NaOAc

The formation of decavanadate is optimized by maintaining a pH range of 4–7. Typical side products include metavanadate, [VO3]−, and hexavanadate, [V6O16]2−, ions.[1]

Structure

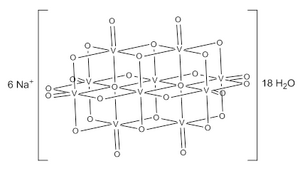

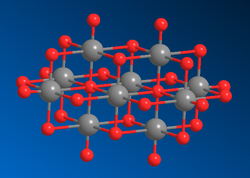

The decavanadate ion consists of 10 fused VO6 octahedra and has D2h symmetry.[3][4][5] The structure of Na6[V10O28]·18H2O has been confirmed with X-ray crystallography.[6]

The decavanadate anions contains three sets of equivalent V atoms (see fig. 1).[3] These include two central VO6 octahedra (Vc) and four each peripheral tetragonal-pyramidal VO5 groups (Va and Vb). There are seven unique groups of oxygen atoms (labeled A through G). Two of these (A) bridge to six V centers, four (B) bridge three V centers, fourteen of these (C, D and E) span edges between pairs of V centers, and eight (F and G) are peripheral.

The oxidation state of vanadium in decavanadate is +5.

Acid-base properties

Aqueous vanadate (V) compounds undergo various self-condensation reactions.[7] Depending on pH, major vanadate anions in solution include VO2(H2O)42+, VO43−, V2O73−, V3O93−, V4O124−, and V10O286−. The anions often reversibly protonate.[5] Decavanadate forms according to this equilibrium:[2][7]

- H3V10O283− ⇌ H2V10O284− + H+

- H2V10O284− ⇌ HV10O285− + H+

- HV10O285−(aq) ⇌ V10O286− + H+

The structure of the various protonation states of the decavanadate ion has been examined by 51V NMR spectroscopy.[5][7] Each species gives three signals; with slightly varying chemical shifts around −425, −506, and −523 ppm relative to vanadium oxytrichloride; suggesting that rapid proton exchange occurs resulting in equally symmetric species.[8] The three protonations of decavanadate have been shown to occur at the bridging oxygen centers, indicated as B and C in figure 1.[8]

Decavanadate is most stable in pH 4–7 region.[1][4][7] Solutions of vanadate turn bright orange at pH 6.5, indicating the presence of decavanadate. Other vanadates are colorless. Below pH 2.0, brown V2O5 precipitates as the hydrate.[3][7]

- V10O286− + 6H+ + 12H2 ⇌ 5V2O5

Potential uses

Decavanadate has been found to inhibit phosphoglycerate mutase, an enzyme which catalyzes step 8 of glycolysis. In addition, decavandate was found to have modest inhibition of Leishmania tarentolae viability, suggesting that decavandate may have a potential use as a topical inhibitor of protozoan parasites.[9]

Related decavanadates

Many decavanadate salts have been characterized. NH4+, Ca2+, Ba2+, Sr2+, and group I decavanadate salts are prepared by the acid-base reaction between V2O5 and the oxide, hydroxide, carbonate, or hydrogen carbonate of the desired positive ion.[1]

- 6 NH3 + 5 V2O5 + 3 H2O ⇌ (NH4)6[V10O28]

Other decavanadates:

- (NH4)6[V10O28]·6H2O[2]

- K6[V10O28]·9H2O[2]

- K6[V10O28]·10H2O[1][2][3]

- Ca3[V10O28]·16H2O[2][3]

- K2Mg2[V10O28]·16H2O[2][3]

- K2Zn2[V10O28]·16H2O[1][2][3]

- Cs2Mg2[V10O28]·16H2O[3]

- Cs4Na2[V10O28]·10H2O[10]

- K4Na2[V10O28]·16H2O[11]

- Sr3[V10O28]·22H2O[10]

- Ba3[V10O28]·19H2O[10]

- [(C6H5)4P]H3V10O28·4CH3CN[8]

- Ag6[V10O28]·4H2O[12][13]

Naturally occurring decavanadates include:

- Ca3V10O28·17 H2O (Pascoite)

- Ca2Mg(V10O28)·16H2O (Magnesiopascoite)

- Na4Mg(V10O28)·24H2O (Huemulite)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Johnson, G.; Murmann, R. K. (1979). "Sodium and Ammonium Decayanadates(V)". Inorganic Syntheses. 19. pp. 140–145. doi:10.1002/9780470132500.ch32. ISBN 978-0-471-04542-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Rossotti, F. J.; Rossotti, H. (1956). "Equilibrium Studies of Polyanions". Acta Chemica Scandinavica 10: 957–984. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.10-0957.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Evans, H. T. Jr (1966). "The molecular structure of the isopoly complex ion, decavanadate". Inorg. Chem. 5: 967–977. doi:10.1021/ic50040a004.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kustin, K.; Pessoa, J. C.; Crans, D. C. (2007). Vandadium: The Versatile Metal. Washington, D. C.: American Chemical Society. ISBN 978-0-8412-7446-4.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Rehder, D. (2008). Bioinorganic Vanadium Chemistry. Wiley & Sons. pp. 13–51. ISBN 978-0-470-06509-9.

- ↑ Durif, P.A.; Averbuch-pouchot, M.T. (1980). "Structure d'un Décavanadate d'Hexasodium Hydraté". Acta Crystallogr. B 36 (3): 680–682. doi:10.1107/S0567740880004116. Bibcode: 1980AcCrB..36..680D.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Tracey, A.S.; Crans, D.C. (1998). Vanadium Compounds. Washington D.C.: American Chemical Society. ISBN 0-8412-3589-9.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Day, V. W.; Klemperer, W. G.; Maltbie, D. J. (1987). "Where Are the Protons in H3V10O283−?". Journal of the American Chemical Society 109 (10): 2991–3002. doi:10.1021/ja00244a022.

- ↑ Turner, Timothy; Nguyen, Victoria; McLauchlan, Craig; Dymon, Zaneta; Dorsey, Benjamin; Hooker, Jaqueline; Jones, Marjorie (March 2012). "Inhibitory effects of decavanadate on several enzymes and Leishmania tarentolae In Vitro". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry 108: 96–104. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.09.009. PMID 22005446. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0162013411002637. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Dametto, A.C.; de Arauju, A.S.; de Souza Correa, R.; Guilherme, L.R.; Massabni, A.C. (2010). "Synthesis, infrared spectroscopy and crystal structure determination of a new decavanadate". J Chem Crystallogr 40 (11): 897–901. doi:10.1007/s10870-010-9759-x.

- ↑ Matias, P.M.; Pessoa, J.C.; Duarte, M.T.; Maderia, C. (2000). "Tetrapotassium disodium decavanadate(V) decahydrate". Acta Crystallogr. C 57 (3): e75–e76. doi:10.1107/S0108270100001530. PMID 15263200. Bibcode: 2000AcCrC..56E..75M.

- ↑ Escobar, M.E.; Baran, E.J. (1981). "Die Schwingungsspektren einiger kristalliner Dekavanadate". Monatshefte für Chemie 112: 43–49. doi:10.1007/BF00906241. http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/146548.

- ↑ Aureliano, Manuel; Crans, Debbie C. (2009). "Decavanadate (V10O6−28) and oxovanadates: Oxometalates with many biological activities". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry 103 (4): 536–546. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.11.010. ISSN 0162-0134. PMID 19110314. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0162013408002882.

|