Company:Symantec

| |

Symantec headquarters in Mountain View, California | |

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

| NASDAQ: SYMC NASDAQ-100 Component S&P 500 Component | |

| Industry | Computer software |

| Founded | March 1, 1982 Sunnyvale, California , United States |

| Founder | Gary Hendrix |

| Headquarters | Mountain View, California , U.S.[1] |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Daniel Schulman (Chairman) Greg Clark (CEO) |

| Products | Security software |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 12,518 (2017)[3] |

| Divisions | List of divisions |

Symantec Corporation /sɪˈmænˌtɛk/ (commonly known as Symantec) is an American software company headquartered in Mountain View, California, United States . The company provides cybersecurity software and services. Symantec is a Fortune 500 company and a member of the S&P 500 stock-market index. The company also has development centers in Pune, Chennai and Bengaluru (India).

On October 9, 2014, Symantec declared it would split into two independent publicly traded companies by the end of 2015. One company would focus on security, the other on information management. On January 29, 2016, Symantec sold its information-management subsidiary, named Veritas Technologies (which Symantec had acquired in 2004)[4] to The Carlyle Group.[5]

The name "Symantec" is a portmanteau of the words "syntax" and "semantics" with "technology".[6]

History

1982 to 1989

Founded in 1982 by Gary Hendrix with a National Science Foundation grant, Symantec was originally focused on artificial intelligence-related projects, including a database program.[7] Hendrix hired several Stanford University natural language processing researchers as the company's first employees, among them Barry Greenstein (professional poker player and developer of the word processor component within Q&A).[7] Hendrix also hired Jerry Kaplan (entrepreneur and author) as a consultant to build the in-RAM database for Q&A.[8]

In 1984, it became clear that the advanced natural language and database system that Symantec had developed could not be ported from DEC minicomputers to the PC.[9] This left Symantec without a product, but with expertise in natural language database query systems and technology.[10] As a result, later in 1984 Symantec was acquired by another, smaller software startup company, C&E Software, founded by Denis Coleman and Gordon Eubanks and headed by Eubanks.[10] C&E Software developed a combined file management and word processing program called Q&A for "question and answer."[10]

The merged company retained the name Symantec.[10] Eubanks became its chairman, Vern Raburn, the former President of the original Symantec, remained as President of the combined company.[11] The new Symantec combined the file management and word processing functionality that C&E had planned, and added an advanced Natural Language query system (designed by Gary Hendrix and engineered by Dan Gordon) that set new standards for ease of database query and report generation. The natural language system was named "The Intelligent Assistant". Turner chose the name of Q&A for Symantec's flagship product, in large part because the name lent itself to use in a short, easily merchandised logo. Brett Walter designed the user interface of Q&A (Brett Walter, Director of Product Management). Q&A was released in November 1985.

During 1986, Vern Raburn and Gordon Eubanks swapped roles, and Eubanks became CEO and president of Symantec, while Raburn became its chairman.[12] Subsequent to this change, Raburn had little involvement with Symantec, and in a few years time, Eubanks added the Chairmanship to his other roles.[citation needed] After a slow start for sales of Q&A in the fall of 1985 and spring of 1986, Turner signed up a new advertising agency called Elliott/Dickens, embarked on an aggressive new advertising campaign, and came up with the "Six Pack Program" in which all Symantec employees, regardless of role, went on the road, training and selling dealer sales staff nationwide in the United States. Turner named it Six Pack because employees were to work six days a week, see six dealerships per day, train six sales representatives per store and stay with friends free or at Motel 6.[13] Simultaneously, a promotion was run jointly with SofSell (which was Symantec's exclusive wholesale distributor in the United States for the first year that Q&A was on the market). This promotion was very successful in encouraging dealers to try Q&A.

During this time, Symantec was advised by Jim Lally and John Doerr — both were board members of Symantec at that stage — (Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers) that if Symantec would cut its expenses and grow revenues enough to achieve cash flow break-even, then KPCB would back the company in raising more venture capital. To accomplish this, the management team worked out a salary reduction schedule where the chairman and the CEO would take zero pay, all vice presidents would take a 50% pay cut, and all other employees' pay was cut by 15%. Two employees were laid off. Eubanks also negotiated a sizable rent reduction on the office space the company had leased in the days of the original Symantec. These expense reductions, combined with strong international sales of Q&A, enabled the company to attain break-even.

The significantly increased traction for Q&A from this re-launch grew Symantec's revenues substantially, along with early success for Q&A in international markets (uniquely a German version was shipped three weeks after the United States version, and it was the first software in the world that supported German Natural Language) following Turner's having placed emphasis on establishing international sales distribution and multiple language versions of Q&A from initial shipment.

In 1985, Rod Turner negotiated the publishing agreement with David Whitney for Symantec's second product, which Turner named NoteIt (an annotation utility for Lotus 1-2-3). It was evident to Turner that NoteIt would confuse the dealer channel if it was launched under the Symantec name, because Symantec had built up interest by that stage in Q&A (but not yet shipped it), and because the low price for the utility would not be initially attractive to the dealer channel until demand had been built up. Turner felt that the product should be marketed under a unique brand name.

Turner and Gordon E. Eubanks, Jr., then chairman of Symantec Corporation, agreed to form a new division of Symantec, and Eubanks delegated the choice of name to Turner. Turner chose the name Turner Hall Publishing, to be a new division of Symantec devoted to publishing third-party software and hardware. The objective of the division was to diversify revenues and accelerate the growth of Symantec. Turner chose the name Turner Hall Publishing, using his last name and that of Dottie Hall (Director of Marketing Communications) in order to convey the sense of a stable, long established, company.[14][15] Turner Hall Publishing's first offering was Note-It, a notation utility add-in for Lotus 1-2-3, which was developed by David Whitney, and licensed to Symantec.[16][17] Its second product was the Turner Hall Card, which was a 256k RAM, half slot memory card, initially made to inexpensively increase the available memory for Symantec's flagship product, Q&A. The Turner Hall division also marketed the card as a standalone product. Turner Hall's third product, also a 1-2-3 add-in was SQZ! a Lotus 1-2-3 spreadsheet compression utility developed by Chris Graham Synex Systems.[18] In the summer of 1986 Eubanks and Turner recruited Tom Byers from Digital Research, to expand the Turner Hall Publishing product family and lead the Turner Hall effort.

By the winter of 1986–87, the Turner Hall Publishing division had achieved success with NoteIt, the Turner Hall Card and SQZ!. The popularity of these products, while contributing a relatively small portion of revenues to Symantec, conveyed the impression that Symantec was already a diversified company, and indeed, many industry participants were under the impression that Symantec had acquired Turner Hall Publishing. In 1987, Byers recruited Ted Schlein into the Turner Hall Product Group to assist in building the product family and in marketing.

Revenues from Q&A, and from Symantec's early launch into the international marketplace, combined with Turner Hall Publishing, generated the market presence and scale that enabled Symantec to make its first merger/acquisition, in February 1987, that of Breakthrough Software, maker of the TimeLine project management software for DOS. Because this was the first time that Symantec had acquired a business that had revenues, inventory and customers, Eubanks chose to change nothing at BreakThrough Software for six months, and the actual merger logistics started in the summer of 1987, with Turner being appointed by Eubanks as general manager of the TimeLine business unit, Turner was made responsible for the successful integration of the company into Symantec and ongoing growth of the business, with P&L. There was a heavy emphasis placed on making the minimum disruption by Eubanks and Turner.

Soon after the acquisition of TimeLine/Breakthrough Software, Eubanks reorganized Symantec, structuring the company around product-centric groups, each having its own development, quality assurance, technical support and product marketing functions, and a General Manager with profit and loss responsibility. Sales, finance and operations were centralized functions that were shared. This structure lent itself well to Symantec's further growth through mergers and acquisitions. Eubanks made Turner general manager of the new TimeLine Product Group, and simultaneously of the Q&A Product Group, and made Tom Byers general manager of the Turner Hall Product Group. Turner continued to build and lead the company's international business and marketing for the whole company.

At the TimeLine Product Group, Turner drove strong marketing, promotion and sales programs in order to accelerate momentum. By 1989 this merger was very successful—product group morale was high, TimeLine development continued apace, and the increased sales and marketing efforts applied built the TimeLine into the clear market lead in PC project management software on DOS. Both the Q&A and TimeLine product groups were healthily profitable. The profit stream and merger success set the stage for subsequent merger and acquisition activity by the company, and indeed funded the losses of some of the product groups that were subsequently acquired.[14] In 1989, Eubanks hired John Laing as VP worldwide sales, and Turner transferred the international division to Laing. Eubanks also recruited Bob Dykes to be Executive Vice President for Operations and Finance, in anticipation of the upcoming IPO. In July 1989 Symantec had its IPO.

1990 to 1999

In May 1990, Symantec announced its intent to merge with and acquire Peter Norton Computing, a developer of various utilities for DOS. Turner was appointed as product group manager for the Norton business, and made responsible for the merger, with P&L responsibility. Ted Schlein was made product group manager for the Q&A business.

The Peter Norton group merger logistical effort began immediately while the companies sought approval for the merger, and in August 1990, Symantec concluded the purchase—by this time the combination of the companies was already complete. Symantec's consumer antivirus and data management utilities are still marketed under the Norton name. At the time of the merger, Symantec had built upon its Turner Hall Publishing presence in the utility market, by introducing Symantec Antivirus for the Macintosh (SAM), and Symantec Utilities for the Macintosh (SUM). These two products were already market leaders on the Mac, and this success made the Norton merger more strategic. Symantec had already begun development of a DOS-based antivirus program one year before the merger with Norton. The management team had decided to enter the antivirus market in part because it was felt that the antivirus market entailed a great deal of ongoing work to stay ahead of new viruses. The team felt that Microsoft would be unlikely to find this effort attractive, which would lengthen the viability of the market for Symantec. Turner decided to use the Norton name for obvious reasons, on what became the Norton Antivirus, which Turner and the Norton team launched in 1991. At the time of the merger, Norton revenues were approximately 20 to 25% of the combined entity. By 1993, while being led by Turner, Norton product group revenues had grown to be approximately 82% of Symantec's total.

At one time Symantec was also known for its development tools, particularly the THINK Pascal, THINK C, Symantec C++, Enterprise Developer and Visual Cafe packages that were popular on the Macintosh and IBM PC compatible platforms. These product lines resulted from acquisitions made by the company in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These businesses and the Living Videotext acquisition were consistently unprofitable for Symantec, and these losses diverted expenditures away from both the Q&A for Windows and the TimeLine for Windows development efforts during the critical period from 1988 through 1992. Symantec exited this business in the late-1990s as competitors such as Metrowerks, Microsoft and Borland gained significant market share.

In 1996, Symantec Corporation was alleged of misleading financial statements in violation of GAAP.[19]

2000 to present

From 1999 to April 2009 Symantec was led by CEO John W. Thompson, a former VP at IBM. At the time, Thompson was the only African-American leading a major US technology company. He was succeeded in April 2009 by the company's long-time Symantec executive Enrique Salem.[20] Under Salem, Symantec completed the acquisition of Verisign's Certificate Authority business, dramatically increasing their share of that market.

Salem was abruptly fired in 2012 for disappointing earnings performance and replaced by Steve Bennett, a former CEO of Intuit and GE executive.[21] In January 2013, Bennett announced a major corporate reorganization, with a goal of reducing costs and improving Symantec's product line. He said that sales and marketing "had been high costs but did not provide quality outcomes". He concluded that "Our system is just broken".[22]

Robert Enderle of CIO.com reviewed the reorganization and noted that Bennett was following the General Electric model of being product-focused instead of customer-focused. He concluded "Eliminating middle management removes a large number of highly paid employees. This will tactically improve Symantec's bottom line but reduce skills needed to ensure high-quality products in the long term."[23]

In March 2014, Symantec fired Steve Bennett from his CEO position and named Michael Brown as interim president and chief executive. Including the interim CEO, Symantec has had 3 CEOs in less than two years.[24][25] On September 25, 2014 Symantec announced the appointment of Michael A. Brown as its President and Chief Executive Officer.[26] Brown had served as the company's interim President and Chief Executive Officer since March 20, 2014.[27] Mr. Brown has served as a member of the Company's Board of Directors since July 2005 following the acquisition of VERITAS Software Corporation. Mr. Brown had served on the VERITAS board of directors since 2003.[28]

In July 2016, Symantec introduced a solution to help carmarkers protect connected vehicles against zero-day attacks. The Symantec Anomaly Detection for Automotive is an IoT solution for manufacturers and uses machine learning to provide in-vehicle security analytics.[29] Greg Clark assumed the position of CEO in August 2016.[30]

In November 2016, Symantec announced its intent to acquire identity theft protection company LifeLock for $2.3 billion.[31]

In August 2017, Symantec announced that it had agreed to sell its business unit that verifies the identity of websites to Thoma Bravo. With this acquisition, Thoma Bravo plans to merge the Symantec business unit with its own web certification company, DigiCert.[32]

On January 4, 2018, Symantec and BT announced their partnership that provides new endpoint security protection.[33]

In May 2018, Symantec initiated an internal audit to address concerns raised by a former employee,[34][35] causing it to delay its annual earnings report.[36]

In August 2018, Symantec announced that the hedge fund Starboard Value had put forward five nominees to stand for election to the Symantec Board of Directors at Symantec's 2018 Annual Meeting of Stockholders.[37] This followed a Schedule 13D filing by Starboard showing that it had accumulated a 5.8% stake in Symantec.[38] In September 2018, Symantec announced that three nominees of Starboard were joining the Symantec board, two with immediate effect (including Starboard Managing Member Peter Feld) and one following the 2018 Annual Meeting of Stockholders.[39]

Demerger

On October 9, 2014, Symantec declared that the company would separate into two independent publicly traded companies by the end of 2015.[40] Symantec will continue to focus on security, while a new company will be established focusing on information management. Symantec confirmed on January 28, 2015 that the information management business would be called Veritas Technologies Corporation, marking a return of the Veritas name.[41] In August 2015, Symantec agreed to sell Veritas to a private equity group led by The Carlyle Group for $8 billion. The sale was completed by February 2016 that turned Veritas into a privately owned company.[42]

Norton products

As of 2015, Symantec's Norton product line includes Norton Security, Norton Small Business, Norton Family, Norton Mobile Security, Norton Online Backup, Norton360, Norton Utilities and Norton Computer Tune Up.[citation needed]

In 2012, PCTools iAntiVirus was rebranded as a Norton product under the name iAntivirus, and released to the Mac App Store. Also in 2012, the Norton Partner Portal was relaunched to support sales to consumers throughout the EMEA technologies.[citation needed]

Mergers and acquisitions

ACT!

In 1993, Symantec acquired ACT! from Contact Software International. Symantec sold ACT! to SalesLogix in 1999. At the time it was the world's most popular CRM application for Windows and Macintosh.[43]

Veritas

On December 16, 2004, Veritas Software and Symantec announced their plans for a merger. With Veritas valued at $13.5 billion, it was the largest software industry merger to date.[44] Symantec's shareholders voted to approve the merger on June 24, 2005; the deal closed successfully on July 2, 2005.[45] July 5, 2005, was the first day of business for the U.S. offices of the new, combined software company. As a result of this merger, Symantec includes storage- and availability-related products in its portfolio, namely Veritas File System (VxFS), Veritas Volume Manager (VxVM), Veritas Volume Replicator (VVR), Veritas Cluster Server (VCS), NetBackup (NBU), Backup Exec (BE) and Enterprise Vault (EV).[citation needed]

On January 29, 2016, Symantec sold Veritas Technologies to The Carlyle Group.[4]

Sygate

On August 16, 2005, Symantec acquired Sygate,[46] a security software firm based in Fremont, California, with about 200 staff.[47] As of November 30, 2005, all Sygate personal firewall products were discontinued.[48]

Altiris

On January 29, 2007, Symantec announced plans to acquire Altiris,[49] and on April 6, 2007, the acquisition was completed.[50] Altiris specializes in service-oriented management software that allows organizations to manage IT assets.[49] It also provides software for web services, security and systems management products. Established in 1998, Altiris is headquartered in Lindon, Utah.[51]

Vontu

On November 5, 2007, Symantec announced its acquisition of Vontu, the leader in Data Loss Prevention (DLP) solutions, for $350 million.[52]

Application Performance Management business

On January 17, 2008, Symantec announced[53] that it was spinning off its Application Performance Management (APM) business and the i3 product line to Vector Capital.[54] Precise Software Solutions took over development, product management, marketing and sales for the APM business, launching as an independent company on September 17, 2008.[55]

PC Tools

On August 18, 2008, Symantec announced the signing of an agreement to acquire PC Tools. Under the agreement, PC Tools would maintain separate operations. The financial terms of the acquisition were not disclosed. In May 2013, Symantec announced they were discontinuing the PC Tools line of internet security software.[56]

In December 2013, Symantec announced they were discontinuing and retiring the entire PC Tools brand and offering a non expiring license to PC Tools Performance Toolkit, PC Tools Registry Mechanic, PC Tools File Recover and PC Tools Privacy Guardian users with an active subscription as of December 4, 2013.[57]

AppStream

On April 18, 2008, Symantec completed the acquisition of AppStream, Inc. (“AppStream”), a nonpublic Palo Alto, California-based provider of endpoint virtualization software. AppStream was acquired to complement Symantec's endpoint management and virtualization portfolio and strategy.[58]

MessageLabs

On October 9, 2008, Symantec announced its intent to acquire Gloucester-based MessageLabs (spun off from Star Internet in 2007) to boost its Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) business. Symantec purchased the online messaging and Web security provider for about $695 million in cash.[59] The acquisition closed on November 17, 2008.[60]

PGP and GuardianEdge

On April 29, 2010, Symantec announced its intent to acquire PGP Corporation and GuardianEdge.[61] The acquisitions closed on June 4, 2010, and provided access to established encryption, key management and technologies to Symantec's customers.[citation needed]

Verisign authentication

On May 19, 2010, Symantec signed a definitive agreement to acquire Verisign’s authentication business unit, which included the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) Certificate, Public Key Infrastructure (PKI), Verisign Trust and Verisign Identity Protection (VIP) authentication services.[62] The acquisition closed on August 9, 2010. In August 2012, Symantec completed its rebranding of the Verisign SSL Certificate Service by renaming the Verisign Trust Seal the Norton Secured Seal.[63]

Rulespace

Acquired in October 10, 2010, RuleSpace is a web categorisation product first developed in 1996.[64] The categorisation is, automated using what Symantec refers to as the Automated Categorization System (ACS). It is used as the base for content filtering by many UK ISP.[citation needed]

Clearwell Systems

On May 19, 2011, Symantec announced the acquisition of Clearwell Systems for approximately $390 million.[65]

LiveOffice

On January 17, 2012, Symantec announced the acquisition of cloud email-archiving company LiveOffice. The acquisition price was $115 million.[66] Last year,[ambiguous] Symantec joined the cloud storage and backup sector with its Enterprise Vault.cloud and Cloud Storage for Enterprise Vault solutions, in addition to a cloud messaging solution, Symantec Instant Messaging Security cloud (IMS.cloud).[citation needed] Symantec stated that the acquisition would add to its information governance products,[66][67] allowing customers to store information on-premises, in Symantec's data centers, or both.

Odyssey Software

On March 2, 2012, Symantec completed the acquisition of Odyssey Software. Odyssey Software's main product was Athena, which was device management software that extended Microsoft System Center solutions, adding the ability to manage, support and control mobile and embedded devices, such as smartphones and ruggedized handhelds.[46][68]

Nukona Inc.

Symantec completed its acquisition of Nukona, a provider of mobile application management (MAM), on April 2, 2012.[69] The acquisition agreement between Symantec and Nukona was announced on March 20, 2012.[70]

NitroDesk Inc.

On May 2014 Symantec acquired NitroDesk, provider of TouchDown, the market-leading third-party EAS mobile application.[71]

Blue Coat Systems

On June 13, 2016 it was announced that Symantec has acquired Blue Coat for $4.65 billion.[72]

Security concerns and controversies

Restatement

On August 9, 2004, the company announced that it discovered an error in its calculation of deferred revenue, which represented an accumulated adjustment of $20 million.[73][74]

Endpoint bug

The arrival of the year 2010 triggered a bug in Symantec Endpoint. Symantec reported that malware and intrusion protection updates with "a date greater than December 31, 2009 11:59pm [were] considered to be 'out of date.'" The company created and distributed a workaround for the issue.[75]

Scan evasion vulnerability

In March 2010, it was reported that Symantec AntiVirus and Symantec Client Security were prone to a vulnerability that might allow an attacker to bypass on-demand virus scanning, and permit malicious files to escape detection.[76][77][citation needed]

Denial-of-service attack vulnerabilities

In January 2011, multiple vulnerabilities in Symantec products that could be exploited by a denial-of-service attack, and thereby compromise a system, were reported. The products involved were Symantec AntiVirus Corporate Edition Server and Symantec System Center.[78]

The November 12, 2012 Vulnerability Bulletin of the United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) reported the following vulnerability for older versions of Symantec's Antivirus system: "The decomposer engine in Symantec Endpoint Protection (SEP) 11.0, Symantec Endpoint Protection Small Business Edition 12.0, Symantec AntiVirus Corporate Edition (SAVCE) 10.x, and Symantec Scan Engine (SSE) before 5.2.8 does not properly perform bounds checks of the contents of CAB archives, which allows remote attackers to cause a denial of service (application crash) or possibly execute arbitrary code via a crafted file."[79]

The problem relates to older versions of the systems and a patch is available. US-CERT rated the seriousness of this vulnerability as a 9.7 on a 10-point scale. The "decomposer engine" is a component of the scanning system that opens containers, such as compressed files, so that the scanner can evaluate the files within.[citation needed]

Scareware lawsuit

In January 2012, James Gross filed a lawsuit against Symantec for distributing fake scareware scanners that purportedly alerted users of issues with their computers. Gross claimed that after the scan, only some of the errors and problems were corrected, and he was prompted by the scanner to purchase a Symantec app to remove the rest. Gross claimed that he bought the app, but it did not speed up his computer or remove the detected viruses. He hired a digital forensics expert to back up this claim. Symantec denied the allegations and said that it would contest the case.[80] Symantec settled a $11 million fund (up to $9 to more than 1 million eligible customers representing the overpaid amount for the app) and the case was dismissed in court.[81][82]

Source code theft

On January 17, 2012, Symantec disclosed that its network had been hacked. A hacker known as "Yama Tough" had obtained the source code for some Symantec software by hacking an Indian government server.[83] Yama Tough released parts of the code, and threatened to release more. According to Chris Paden, a Symantec spokesman, the source code that was taken was for Enterprise products that were between five and six years old.[83]

On September 25, 2012, an affiliate of the hacker group Anonymous published source code from Norton Utilities.[84] Symantec confirmed that it was part of the code that had been stolen earlier, and that the leak included code for 2006 versions of Norton Utilities, pcAnywhere and Norton Antivirus.[84]

Verisign data breach

In February 2012, it was reported that Verisign's network and data had been hacked repeatedly in 2010, but that the breaches had not been disclosed publicly until they were noted in an SEC filing in October 2011.[85] Verisign did not provide information about whether the breach included its certificate authority business, which was acquired by Symantec in late 2010.[85] Oliver Lavery, Director of Security and Research for nCircle, asked rhetorically, "Can we trust any site using Verisign SSL certificates? Without more clarity, the logical answer is no."[86][87]

pcAnywhere exploit

On February 17, 2012, details of an exploit of pcAnywhere were posted. The exploit would allow attackers to crash pcAnywhere on computers running Windows.[88] Symantec released a hotfix for the issue twelve days later.[89]

Hacking of The New York Times network

According to Mandiant, Symantec security products used by The New York Times detected only one of 45 pieces of malware that were installed by Chinese hackers on the newspaper's network during a three-month period in late 2012.[90] Symantec responded:

"Advanced attacks like the ones the New York Times described in the following article, <http://nyti.ms/TZtr5z>, underscore how important it is for companies, countries and consumers to make sure they are using the full capability of security solutions. The advanced capabilities in our [E]ndpoint offerings, including our unique reputation-based technology and behavior-based blocking, specifically target sophisticated attacks. Turning on only the signature-based anti-virus components of [E]ndpoint solutions alone [is] not enough in a world that is changing daily from attacks and threats. We encourage customers to be very aggressive in deploying solutions that offer a combined approach to security. Anti-virus software alone is not enough".[91]

Intellectual Ventures suit

In February 2015, Symantec was found guilty of two counts of patent infringement in a suit by Intellectual Ventures Inc and ordered to pay $17 million in compensation and damages,[92] In September 2016, this decision was reversed on appeal by the Federal Circuit.[93][94]

Sustaining digital certificate security

On September 18, 2015, Google notified Symantec that the latter issued 23 test certificates for five organizations, including Google and Opera, without the domain owners' knowledge.[95] Symantec performed another audit and announced that an additional 164 test certificates were mis-issued for 76 domains and 2,458 test certificates were mis-issued for domains that had never been registered. Google requested that Symantec update the public incident report with proven analysis explaining the details on each of the failures.[96]

The company was asked to report all the certificates issued to the Certificate Transparency log henceforth.[97][98] Symantec has since reported implementing Certificate Transparency for all its SSL Certificates. Above all, Google has insisted that Symantec execute a security audit by a third party and to maintain tamper-proof security audit logs.[97]

Google and Symantec clash on website security checks

On March 24, 2017, Google stated that it had lost confidence in Symantec, after the latest incident of improper certificate issuance.[99][100] Google says millions of existing Symantec certificates will become untrusted in Google Chrome over the next 12 months. According to Google, Symantec partners issued at least 30,000 certificates of questionable validity over several years, but Symantec disputes that number.[101] Google said Symantec failed to comply with industry standards and could not provide audits showing the necessary documentation.[102][103]

Google’s Ryan Sleevi said that Symantec partnered with other CAs (CrossCert (Korea Electronic Certificate Authority), Certisign Certificatadora Digital, Certsuperior S. de R. L. de C.V., and Certisur S.A.) who did not follow proper verification procedures leading to the misissuance of certificates.[104]

Following discussions in which Google had required that Symantec migrate Symantec-branded certificate issuance operations a non-Symantec-operated “Managed Partner Infrastructure”,[105] a deal was announced whereby DigiCert acquired Symantec's website security business.[106] In September 2017, Google announced that starting with Chrome 66, "Chrome will remove trust in Symantec-issued certificates issued prior to June 1, 2016".[107] Google further stated that "by December 1, 2017, Symantec will transition issuance and operation of publicly-trusted certificates to DigiCert infrastructure, and certificates issued from the old Symantec infrastructure after this date will not be trusted in Chrome."[107] Google predicted that toward the end of October, 2018, with the release of Chrome 70, the browser would omit all trust in Symantec’s old infrastructure and all of the certificates it had issued, affecting most certificates chaining to Symantec roots.[107] Mozilla Firefox will also remove trust in Symantec-issued certificates by Firefox 63, due to be released on October 23, 2018.[108]

See also

- Comparison of antivirus software

- Comparison of computer viruses

- Huawei Symantec, a joint venture between Huawei and Symantec

- List of mergers and acquisitions by Symantec

- Web blocking in the United Kingdom - Technologies

- Symantec behavior analysis technologies SONAR and AntiBot

References

- ↑ "Contact Us - Symantec Corp". Symantec.com. http://www.symantec.com/about/profile/contact.jsp. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Financial Tables". Symantec Investor Relations. https://finance.yahoo.com/q/is?s=SYMC&annual. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- ↑ "2017 Corporate Responsibility Report". Symantec. https://www.symantec.com/content/dam/symantec/docs/reports/2017-corporate-responsibility-report-en.pdf. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bray, Chad (August 11, 2015). "Carlyle Group and Other Investors to Acquire Veritas Technologies for $8 Billion". The New York Times Company. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/12/business/dealbook/carlyle-group-veritas-technologies-symantec-deal.html?_r=1.

- ↑ Kuranda, Sarah (January 29, 2016). "Partners Cheer the Official Closing Date of Symantec Split". CRN. http://m.crn.com/news/security/300079555/partners-cheer-the-official-closing-date-of-symantec-split.htm. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Symantec at 25: A short history". Symantec Corporation. https://www.symantec.com/content/en/us/about/media/Symantec_at_25_A_Short_History.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Slaughter, S.A. (2014). A Profile of the Software Industry: Emergence, Ascendance, Risks, and Rewards. 2014 digital library. Business Expert Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-60649-655-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=IXw6BAAAQBAJ&pg=PT69. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ Spicer, Dag (November 19, 2004). "Oral History of Gary Hendrix". Computer History Museum CHM Ref: X3008.2005: 24. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140323232514/http://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/access/text/Oral_History/102657945.05.01-acc.pdf. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ↑ Springer, P.J. (2015). Cyber Warfare: A Reference Handbook: A Reference Handbook. Contemporary World Issues. ABC-CLIO. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-61069-444-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=S6egBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA193. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Jones, C. (2014). The Technical and Social History of Software Engineering. Addison-Wesley. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-321-90342-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=BFkXAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA198. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ "From the News Desk". InfoWorld. September 14, 1984. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ci8EAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA9&lpg=PA9&dq=Vern+Raburn+CEO+of+symantec+C%26E&source=bl&ots=QyAnZo9Mt6&sig=WLebb3gnCC6He9dzifM7GOzYO5E&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjn5c2wkanTAhXLQyYKHWjkDhcQ6AEIODAD#v=onepage&q=Vern%20Raburn%20CEO%20of%20symantec%20C%26E&f=false. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ AI Trends. DM Data, Incorporated. 1985. https://books.google.com/books?id=1k8kAQAAMAAJ. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ Jones, C. (2014). The Technical and Social History of Software Engineering. Addison-Wesley. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-321-90342-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=BFkXAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA199. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Gordon Eubanks Oral History, Computerworld Honors Program, Daniel S. Morrow, November 8, 2000". Google. https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:GaxdaUdMgCIJ:www.cwhonors.org/archives/histories/Eubanks.pdf+%22Turner+Hall+Publishing%22&hl=en&gl=ca&sig=AHIEtbQhf3lmxre17qqPIDDtN8oTAMA5Hw. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ↑ "RasterOps-Truevison adds two industry leaders to board of directors; company names Walter W., Tuesday, March 21, 1995". Business Wire. Archived from the original on March 28, 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090328115712/http://www.allbusiness.com/company-activities-management/board-management/7109119-1.html. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ↑ U.S.. "Symantec". Answers.com. http://www.answers.com/topic/symantec. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Company Histories: Symantec Corporation, Funding Universe". Fundinguniverse.com. http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/Symantec-Corporation-Company-History.html. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Hendren and Associates". Hendrenet.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110711162458/http://hendrenet.com/synex.htm. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Class action suit filed against Symantec Corporation and its officers and directors alleging misrepresentations, false financial statements and insider trading.". Business Wire. August 14, 1996. http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Class+action+suit+filed+against+Symantec+Corporation+and+its+officers...-a018576660. Retrieved Jul 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Enrique Salem". 2012. Archived from the original on December 20, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20121220015950/http://www.symantec.com/about/news/resources/press_kits/detail.jsp?pkid=enrique_salem. Retrieved 2013-06-11.

- ↑ Finkle, Jim (July 25, 2012). "Symantec fires CEO, successor begins turnaround effort". Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/2012/07/25/us-symantec-ceo-idUSBRE86O13620120725. Retrieved 2013-07-11.

- ↑ Ellen Messmer (January 24, 2013). "Symantec CEO on reorg: 'our system is just broken'". Computerworld. http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/9236174/Symantec_CEO_on_reorg_our_system_is_just_broken_. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ Rob Enderle (January 25, 2013). "Symantec Reorganization Offers a Lesson on Knowing When to Leave". CIO. http://www.cio.com/article/727598/Symantec_Reorganization_Offers_a_Lesson_on_Knowing_When_to_Leave. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ Schwartz, Mathew (March 21, 2004). "Symantec Fires CEO In Surprise Move". Dark Reading. http://www.informationweek.com/security/security-monitoring/symantec-fires-ceo-in-surprise-move/d/d-id/1127848. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ Yadron, Danny (March 20, 2014). "Symantec Fires CEO Steve Bennett". https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303802104579451622038515000. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ Stynes, Tess (September 25, 2014). "Symantec Appoints Brown as CEO". https://www.wsj.com/articles/symantec-appoints-brown-as-ceo-1411677167.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters (March 20, 2014). "UPDATE 2-Symantec fires CEO Bennett". https://www.reuters.com/article/symantec-ceo-idUSL3N0MH4HZ20140320.

- ↑ "Symantec Appoints Michael A. Brown CEO". Symantec Press Release. https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/symantec-welcomes-new-ceo. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ News18.com. “Symantec Launches New System to Protect Connected Vehicles From Hack Attacks.” July 14, 2016. July 14, 2016.

- ↑ Henderson, James (June 13, 2016). "Aussie takes charge as Symantec closes in on $4.6 billion Blue Coat buyout". ARN. http://www.arnnet.com.au/article/601551/symantec-fills-security-ceo-gaps-4-6-billion-blue-coat-buyout/.

- ↑ Molina, Brett. "Symantec to acquire LifeLock for $2.3B". USA Today (2016-11-21). https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/news/2016/11/21/symantec-acquire-lifelock-23b/94208924. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- ↑ Reuters. “Symantec Plans to Sell This Business for Nearly $1 Billion.” August 2, 2017. August 29, 2017.

- ↑ VanillaPlus. "BT and Symantec partner to provide best-in-class endpoint security protection." Jan 04, 2018. Retrieved Jan 5, 2018.

- ↑ Salinas, Sara (2018-05-11). "Symantec suffers worst day in 17 years after news of internal audit". https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/11/symantec-symc-loses-a-third-of-its-value-after-news-of-audit.html.

- ↑ Reisinger, Don (May 11, 2018). "Symantec Is Conducting an Mysterious Internal Investigation as shares take a tumble". http://fortune.com/2018/05/11/symantec-internal-investigation/.

- ↑ "Symantec says annual report may be delayed due to investigation". May 10, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-symantec-results/symantec-reports-smaller-quarterly-loss-idUSKBN1IB2VY.

- ↑ Symantec Confirms Receipt of Director Nominations; http://investor.symantec.com/About/Investors/press-releases/press-release-details/2018/Symantec-Confirms-Receipt-of-Director-Nominations/default.aspx

- ↑ Balu, Nivedita and Panchadar, Arjun; Starboard eyes Symantec board seats after taking stake; Reuters Technology News; August 16, 2018; https://www.reuters.com/article/us-symantec-starboard-stake/starboard-eyes-symantec-board-seats-after-taking-stake-idUSKBN1L10EN

- ↑ RaiBalu, Sonam; Symantec names three Starboard nominees to board; Business News; September 17, 2018; https://www.reuters.com/article/us-symantec-starboard/symantec-appoints-starboards-peter-feld-to-its-board-idUSKCN1LX2EW

- ↑ "Symantec latest company to split in two". BBC News. October 10, 2014. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-29563475. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- ↑ Brown, Michael. "New Veritas Name Blends our History and Vision for Tomorrow’s Data Challenges". Symantec. http://www.symantec.com/connect/announcing-veritas. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ↑ Corporate press release, Symantec and Veritas separation, http://www.symantec.com/content/en/us/enterprise/veritas/other_resources/aug-symantec-separation-update-for-customers-en.pdf, retrieved 2016-02-15

- ↑ Darrow, Barbara (December 7, 1999). "Symantec To Sell ACT To SalesLogix". CRN.com. http://www.crn.com/news/channel-programs/18811391/symantec-to-sell-act-to-saleslogix.htm;jsessionid=XLUTh0qChZ1yuNbv27M2nw**.ecappj03. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ↑ Lee, Dan (August 18, 2014). "2004: Symantec to buy Veritas for $13.5 billion". http://www.mercurynews.com/2014/08/18/2004-symantec-to-buy-veritas-for-13-5-billion/. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ Flynn, Laurie J. (June 25, 2005). "Shareholders Approve Symantec-Veritas Software Merger". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/06/25/technology/shareholders-approve-symantecveritas-software-merger.html. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Das, Sejuti (June 15, 2016). "Symantec's on a roll: 15 merger and acquisition deals you need to know". http://www.channelworld.in/features/symantecs-roll-15-merger-and-acquisition-deals-you-need-know. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ Roberts, Paul F. (August 16, 2005). "Symantec Acquires Endpoint-Security Company Sygate". http://www.eweek.com/security/symantec-acquires-endpoint-security-company-sygate. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ Savvides, Lexy (November 29, 2005). "Symantec scraps Sygate consumer firewall". https://www.cnet.com/uk/news/symantec-scraps-sygate-consumer-firewall/. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Editorial, Reuters (January 29, 2007). "Symantec to acquire Altiris in $830 mln deal". https://www.reuters.com/article/us-symantec-altiris-idUSN2947872520070129. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Symantec Completes Acquisition of Altiris". April 10, 2007. http://www.pcworld.idg.com.au/article/182194/symantec_completes_acquisition_altiris/. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ (in de) Computerworld. IDG Enterprise. p. 69. https://books.google.com/books?id=EE9uNPV85VgC&pg=PA69. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters (November 5, 2007). "UPDATE 1-Symantec says to acquire Vontu for $350 million". https://www.reuters.com/article/vontu-symantec-idUSN0531206820071105. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Symantec to Sell Application Performance Management Business to Vector Capital". Symantec.com. http://www.symantec.com/about/news/release/article.jsp?prid=20080117_01. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ↑ Dubie, Denise (January 18, 2008). "Symantec dumps application performance management business". http://www.networkworld.com/article/2282443/infrastructure-management/symantec-dumps-application-performance-management-business.html. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ "The new Precise to redefine application performance management". precise.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20100928194100/http://precise.com/news/press/2008-0816_performance.asp. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Download PC Performance & Computer Registry Software | PC Tools by Symantec". Pctools.com. 2013-05-18. http://www.pctools.com/norton-offer/pctEOL/. Retrieved 2013-07-11.

- ↑ "Download PC Performance & Computer Registry Software | PC Tools by Symantec". Pctools.com. 2013-12-04. http://www.pctools.com/product-eol/index/faq/utility/. Retrieved 2014-01-15.

- ↑ http://www.wikinvest.com/stock/Symantec_(SYMC)/Appstream_Purchase

- ↑ Stafford, Philip (October 9, 2008). "MessageLabs sold to Symantec for £397m". https://www.ft.com/content/dde2e558-959b-11dd-aedd-000077b07658. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Symantec Acquires MessageLabs: Bolsters SaaS Messaging Security Offerings". November 17, 2008. https://enterprisemanagement.com/research/asset.php/1095/Symantec-Acquires-MessageLabs:--Bolsters-SaaS-Messaging-Security-Offerings. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ Messmer, Ellen (April 29, 2010). "Symantec buying PGP Corp., GuardianEdge for $370 million". http://www.networkworld.com/article/2209091/data-center/symantec-buying-pgp-corp---guardianedge-for--370-million.html. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ Termanini, R. (2016). The Cognitive Early Warning Predictive System Using the Smart Vaccine: The New Digital Immunity Paradigm for Smart Cities and Critical Infrastructure. CRC Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4987-2653-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=G4lUCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA85. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ "VeriSign Rebrands To Norton - Get Norton Secured Seal For Your Site". Trustico.com. 2012-04-15. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130729015126/http://www.trustico.com/rebranding/verisign-to-norton-rebranding.php. Retrieved 2013-07-11.

- ↑ Kaplan, Dan (October 20, 2010). "Symantec buys RuleSpace for URL filtering technology". https://www.scmagazine.com/news/symantec-buys-rulespace-for-url-filtering-technology/article/558270/. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters (May 19, 2011). "Symantec buys data experts Clearwell for $390 million". https://www.reuters.com/article/us-symantec-idUSTRE74I7D020110519. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Dignan, Larry (January 17, 2012). "Symantec picks up LiveOffice for $115 million, bolsters cloud archiving". http://www.zdnet.com/article/symantec-picks-up-liveoffice-for-115-million-bolsters-cloud-archiving/. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ Kirk, Jeremy (January 16, 2012). "Symantec Acquires LiveOffice Cloud-Based Archiving Company". http://www.cio.com/article/2400460/cloud-infrastructure/symantec-acquires-liveoffice-cloud-based-archiving-company.html. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ Howley, Daniel P. (July 17, 2012). "Symantec Beefs Up Enterprise Mobile Security Offerings". http://www.laptopmag.com/articles/symantec-beefs-up-enterprise-mobile-security-offerings. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Symantec Completes Acquisition of Nukona". April 16, 2012. https://www.symantec.com/about/newsroom/press-releases/2012/symantec_0416_01. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ Messmer, Ellen (March 20, 2012). "Symantec to acquire Nukona to assist in BYOD strategy". http://www.networkworld.com/article/2186998/smartphones/symantec-to-acquire-nukona-to-assist-in-byod-strategy.html. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ Kirk, Jeremy (May 28, 2014). "Symantec acquires NitroDesk for email security on Android". http://www.pcworld.com/article/2248060/symantec-acquires-nitrodesk-for-email-security-on-android.html. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ↑ McMillan, Robert; McMillan, Robert (June 12, 2016). "Symantec Set to Buy Blue Coat Systems in $4.65 Billion Deal". https://www.wsj.com/articles/symantec-set-to-buy-blue-coat-systems-in-4-65-billion-deal-1465774721. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Technology Briefing - Software: Symantec Cuts Profit On Accounting Error". August 10, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/08/10/business/technology-briefing-software-symantec-cuts-profit-on-accounting-error.html. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ McMillan, Robert (August 10, 2004). "Symantec lowers earnings results after software glitch". http://www.computerworld.com/article/2566543/security0/symantec-lowers-earnings-results-after-software-glitch.html. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ Greene, Tim (January 6, 2010). "Is It Y2K All Over Again in 2010?". http://www.pcworld.com/article/186044/y2k_in_2010.html. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Symantec AntiVirus Scan Evasion Vulnerability". http://www.securityfocus.com/bid/38219/discuss. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Security Advisories Relating to Symantec Products - Symantec Event Manipulation Potential Scan Bypass". http://www.symantec.com/security_response/securityupdates/detail.jsp?fid=security_advisory&pvid=security_advisory&year=2010&suid=20100217_00. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Multiple vulnerabilities in Symantec products". HelpNet Security. January 27, 2011. http://www.net-security.org/secworld.php?id=10503. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Vulnerability Summary for the Week of November 12, 2012 - US-CERT". United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team. http://www.us-cert.gov/cas/bulletins/SB12-324.html. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ Yin, Sara (2012-01-12). "Symantec Sued for Scareware Tactics". Ziff Davis. http://securitywatch.pcmag.com/none/292826-symantec-sued-for-scareware-tactics. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- ↑ McLernon, Sean (2013-03-18). "Symantec Inks $11M Deal Ending Claims It Used Scare Tactics". Portfolio Media. https://www.law360.com/articles/424823/symantec-inks-11m-deal-ending-claims-it-used-scare-tactics.

- ↑ Breyer, Charles R. (2012-07-31). "Filing 49: Order by Judge Charles R. Breyer granting 38 Motion to Dismiss". Gross v. Symantec Corporation. https://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/california/candce/3:2012cv00154/250294/49/.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Gregg Keizer (2012-01-17). "Symantec backtracks, admits own network hacked". Computerworld. http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/9223495/Symantec_backtracks_admits_own_network_hacked.html. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Constantin, Lucian (September 25, 2012). "Symantec: Leaked Norton Utilities 2006 source code already published months ago". http://www.pcworld.com/article/2010584/symantec-leaked-norton-utilities-2006-source-code-already-published-months-ago.html. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Menn, Joseph (February 2, 2012). "Key Internet operator VeriSign hit by hackers". https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hacking-verisign-idUSTRE8110Z820120202. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ Bradley, Tony (February 2, 2012). "VeriSign Hacked: What We Don't Know Might Hurt Us". PCWorld. http://www.pcworld.com/article/249242/verisign_hacked_what_we_dont_know_might_hurt_us.html. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ Albanesius, Chloe. "VeriSign Hacked Multiple Times in 2010". PC Magazine. https://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2399773,00.asp.

- ↑ Keizer, Gregg (February 23, 2012). "pcAnywhere exploit hackers could hijack 200,000 Windows PCs". http://www.computerworlduk.com/it-vendors/pcanywhere-exploit-hackers-could-hijack-200000-windows-pcs-3339638/. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Claims by Anonymous about Symantec Source Code". Symantec. http://www.symantec.com/theme.jsp?themeid=anonymous-code-claims%7ccc.

- ↑ Perlroth, Nicole (January 31, 2013). "Hackers in China Attacked The Times for Last 4 Months". The New York Times. http://cn.nytimes.com/china/20130131/c31hack/en-us/. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Symantec Statement Regarding New York Times Cyber Attack". Symantec Official blog. http://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/symantec-statement-regarding-new-york-times-cyber-attack.

- ↑ Robinson, Teri. "Symantec to pay $17M in damages for patent violations". SC Magazine. http://www.scmagazine.com/jury-finds-symantec-guilty-on-two-counts-of-patent-infringement/article/397090/. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ Jeff John Roberts (October 3, 2016). "Here’s Why Software Patents Are in Peril After the Intellectual Ventures Ruling". Fortune Magazine. http://fortune.com/2016/10/03/software-patents/. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ Dennis Crouch (October 2, 2016). "First Amendment Finally Reaches Patent Law". PatentlyO. http://patentlyo.com/patent/2016/10/amendment-finally-reaches.html. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ Goodin, Dan (October 29, 2015). "Still fuming over HTTPS mishap, Google makes Symantec an offer it can’t refuse". https://arstechnica.com/security/2015/10/still-fuming-over-https-mishap-google-gives-symantec-an-offer-it-cant-refuse/. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Google threatens action against Symantec-issued SSL certificates following botched investigation" (in en). PCWorld. https://www.pcworld.com/article/2999146/encryption/google-threatens-action-against-symantec-issued-certificates-following-botched-investigation.html.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Constantin, Lucian (October 29, 2015). "Google threatens action against Symantec-issued SSL certificates following botched investigation". http://www.pcworld.com/article/2999146/encryption/google-threatens-action-against-symantec-issued-certificates-following-botched-investigation.html. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Google slams Symantec over Certificate Transparency trouble". April 16, 2017. http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/news/4500256515/Google-slams-Symantec-over-Certificate-Transparency-trouble. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ Constantin, Lucian. "To punish Symantec, Google may distrust a third of the web's SSL certificates". PC World. http://www.pcworld.com/article/3184660/security/to-punish-symantec-google-may-distrust-a-third-of-the-webs-ssl-certificates.html. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ Fariñas, Rafael (March 26, 2017). "Symantec loses Google’s trust over fishy SSL Certificates". The USB Port. http://theusbport.com/symantec-loses-googles-trust-over-fishy-ssl-certificates/26558. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- ↑ "To punish Symantec, Google may distrust a third of the web's SSL certificates". http://www.pcworld.idg.com.au/article/616592/punish-symantec-google-may-distrust-third-web-ssl-certificates/. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ↑ Goodin, Dan (March 24, 2017). "Google takes Symantec to the woodshed for mis-issuing 30,000 HTTPS certs". Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/security/2017/03/google-takes-symantec-to-the-woodshed-for-mis-issuing-30000-https-certs/. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ Cimpanu, Catalin. "Google Reducing Trust in Symantec Certificates Following Numerous Slip-Ups". Bleeping Computer. https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/google-reducing-trust-in-symantec-certificates-following-numerous-slip-ups/. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ Conger, Kate (March 27, 2017). "Google is fighting with Symantec over encrypting the internet". TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2017/03/27/google-is-fighting-with-symantec-over-encrypting-the-internet/. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ Fisher, Darin (July 27, 2017). "Re: [blink-dev Intent to Deprecate and Remove: Trust in existing Symantec-issued Certificates"]. blink-dev@chromium.org Google Group. https://groups.google.com/a/chromium.org/d/msg/blink-dev/eUAKwjihhBs/El1mH8S6AwAJ.

- ↑ Merrill, John (August 2, 2017). "DigiCert to Acquire Symantec’s Website Security Business". DigiCert. https://www.digicert.com/blog/digicert-to-acquire-symantec-website-security-business/.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 107.2 O’Brien, Devon; Sleevi, Ryan; Whalley, Andrew (September 11, 2017). "Chrome’s Plan to Distrust Symantec Certificates". Google Security Blog. https://security.googleblog.com/2017/09/chromes-plan-to-distrust-symantec.html.

- ↑ Thayer, Wayne (July 30, 2018). "Update on the Distrust of Symantec TLS Certificates". Mozilla Security Blog. https://blog.mozilla.org/security/2018/07/30/update-on-the-distrust-of-symantec-tls-certificates/.

External links

- Business data for Symantec:

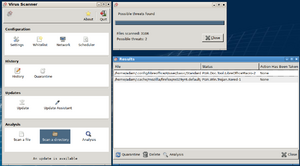

Antivirus software (abbreviated to AV software), also known as anti-malware, is a computer program used to prevent, detect, and remove malware.

Antivirus software was originally developed to detect and remove computer viruses, hence the name. However, with the proliferation of other malware, antivirus software started to protect against other computer threats. Some products also include protection from malicious URLs, spam, and phishing.[1]

History

1949–1980 period (pre-antivirus days)

Although the roots of the computer virus date back as early as 1949, when the Hungarian scientist John von Neumann published the "Theory of self-reproducing automata",[2] the first known computer virus appeared in 1971 and was dubbed the "Creeper virus".[3] This computer virus infected Digital Equipment Corporation's (DEC) PDP-10 mainframe computers running the TENEX operating system.[4][5]

The Creeper virus was eventually deleted by a program created by Ray Tomlinson and known as "The Reaper".[6] Some people consider "The Reaper" the first antivirus software ever written – it may be the case, but it is important to note that the Reaper was actually a virus itself specifically designed to remove the Creeper virus.[6][7]

The Creeper virus was followed by several other viruses. The first known that appeared "in the wild" was "Elk Cloner", in 1981, which infected Apple II computers.[8][9][10]

In 1983, the term "computer virus" was coined by Fred Cohen in one of the first ever published academic papers on computer viruses.[11] Cohen used the term "computer virus" to describe programs that: "affect other computer programs by modifying them in such a way as to include a (possibly evolved) copy of itself."[12] (note that a more recent definition of computer virus has been given by the Hungarian security researcher Péter Szőr: "a code that recursively replicates a possibly evolved copy of itself").[13][14]

The first IBM PC compatible "in the wild" computer virus, and one of the first real widespread infections, was "Brain" in 1986. From then, the number of viruses has grown exponentially.[15][16] Most of the computer viruses written in the early and mid-1980s were limited to self-reproduction and had no specific damage routine built into the code. That changed when more and more programmers became acquainted with computer virus programming and created viruses that manipulated or even destroyed data on infected computers.[17]

Before internet connectivity was widespread, computer viruses were typically spread by infected floppy disks. Antivirus software came into use, but was updated relatively infrequently. During this time, virus checkers essentially had to check executable files and the boot sectors of floppy disks and hard disks. However, as internet usage became common, viruses began to spread online.[18]

1980–1990 period (early days)

There are competing claims for the innovator of the first antivirus product. Possibly, the first publicly documented removal of an "in the wild" computer virus (i.e. the "Vienna virus") was performed by Bernd Fix in 1987.[19][20]

In 1987, Andreas Lüning and Kai Figge, who founded G Data Software in 1985, released their first antivirus product for the Atari ST platform.[21] In 1987, the Ultimate Virus Killer (UVK) was also released.[22] This was the de facto industry standard virus killer for the Atari ST and Atari Falcon, the last version of which (version 9.0) was released in April 2004.[citation needed] In 1987, in the United States, John McAfee founded the McAfee company (was part of Intel Security[23]) and, at the end of that year, he released the first version of VirusScan.[24] Also in 1987 (in Czechoslovakia), Peter Paško, Rudolf Hrubý, and Miroslav Trnka created the first version of NOD antivirus.[25][26]

In 1987, Fred Cohen wrote that there is no algorithm that can perfectly detect all possible computer viruses.[27]

Finally, at the end of 1987, the first two heuristic antivirus utilities were released: Flushot Plus by Ross Greenberg[28][29][30] and Anti4us by Erwin Lanting.[31] In his O'Reilly book, Malicious Mobile Code: Virus Protection for Windows, Roger Grimes described Flushot Plus as "the first holistic program to fight malicious mobile code (MMC)."[32]

However, the kind of heuristic used by early AV engines was totally different from those used today. The first product with a heuristic engine resembling modern ones was F-PROT in 1991.[33] Early heuristic engines were based on dividing the binary into different sections: data section, code section (in a legitimate binary, it usually starts always from the same location). Indeed, the initial viruses re-organized the layout of the sections, or overrode the initial portion of a section in order to jump to the very end of the file where malicious code was located—only going back to resume execution of the original code. This was a very specific pattern, not used at the time by any legitimate software, which represented an elegant heuristic to catch suspicious code. Other kinds of more advanced heuristics were later added, such as suspicious section names, incorrect header size, regular expressions, and partial pattern in-memory matching.

In 1988, the growth of antivirus companies continued. In Germany, Tjark Auerbach founded Avira (H+BEDV at the time) and released the first version of AntiVir (named "Luke Filewalker" at the time). In Bulgaria, Vesselin Bontchev released his first freeware antivirus program (he later joined FRISK Software). Also Frans Veldman released the first version of ThunderByte Antivirus, also known as TBAV (he sold his company to Norman Safeground in 1998). In Czechoslovakia, Pavel Baudiš and Eduard Kučera started avast! (at the time ALWIL Software) and released their first version of avast! antivirus. In June 1988, in South Korea , Ahn Cheol-Soo released its first antivirus software, called V1 (he founded AhnLab later in 1995). Finally, in autumn 1988, in the United Kingdom, Alan Solomon founded S&S International and created his Dr. Solomon's Anti-Virus Toolkit (although he launched it commercially only in 1991 – in 1998 Solomon's company was acquired by McAfee). In November 1988 a professor at the Panamerican University in Mexico City named Alejandro E. Carriles copyrighted the first antivirus software in Mexico under the name "Byte Matabichos" (Byte Bugkiller) to help solve the rampant virus infestation among students.[34]

Also in 1988, a mailing list named VIRUS-L[35] was started on the BITNET/EARN network where new viruses and the possibilities of detecting and eliminating viruses were discussed. Some members of this mailing list were: Alan Solomon, Eugene Kaspersky (Kaspersky Lab), Friðrik Skúlason (FRISK Software), John McAfee (McAfee), Luis Corrons (Panda Security), Mikko Hyppönen (F-Secure), Péter Szőr, Tjark Auerbach (Avira) and Vesselin Bontchev (FRISK Software).[35]

In 1989, in Iceland, Friðrik Skúlason created the first version of F-PROT Anti-Virus (he founded FRISK Software only in 1993). Meanwhile, in the United States, Symantec (founded by Gary Hendrix in 1982) launched its first Symantec antivirus for Macintosh (SAM).[36][37] SAM 2.0, released March 1990, incorporated technology allowing users to easily update SAM to intercept and eliminate new viruses, including many that didn't exist at the time of the program's release.[38]

In the end of the 1980s, in United Kingdom, Jan Hruska and Peter Lammer founded the security firm Sophos and began producing their first antivirus and encryption products. In the same period, in Hungary, also VirusBuster was founded (which has recently being incorporated by Sophos).

1990–2000 period (emergence of the antivirus industry)

In 1990, in Spain, Mikel Urizarbarrena founded Panda Security (Panda Software at the time).[39] In Hungary, the security researcher Péter Szőr released the first version of Pasteur antivirus. In Italy, Gianfranco Tonello created the first version of VirIT eXplorer antivirus, then founded TG Soft one year later.[40]

In 1990, the Computer Antivirus Research Organization (CARO) was founded. In 1991, CARO released the "Virus Naming Scheme", originally written by Friðrik Skúlason and Vesselin Bontchev.[41] Although this naming scheme is now outdated, it remains the only existing standard that most computer security companies and researchers ever attempted to adopt. CARO members includes: Alan Solomon, Costin Raiu, Dmitry Gryaznov, Eugene Kaspersky, Friðrik Skúlason, Igor Muttik, Mikko Hyppönen, Morton Swimmer, Nick FitzGerald, Padgett Peterson, Peter Ferrie, Righard Zwienenberg and Vesselin Bontchev.[42][43]

In 1991, in the United States, Symantec released the first version of Norton AntiVirus. In the same year, in the Czech Republic, Jan Gritzbach and Tomáš Hofer founded AVG Technologies (Grisoft at the time), although they released the first version of their Anti-Virus Guard (AVG) only in 1992. On the other hand, in Finland , F-Secure (founded in 1988 by Petri Allas and Risto Siilasmaa – with the name of Data Fellows) released the first version of their antivirus product. F-Secure claims to be the first antivirus firm to establish a presence on the World Wide Web.[44]

In 1991, the European Institute for Computer Antivirus Research (EICAR) was founded to further antivirus research and improve development of antivirus software.[45][46]

In 1992, in Russia, Igor Danilov released the first version of SpiderWeb, which later became Dr.Web.[47]

In 1994, AV-TEST reported that there were 28,613 unique malware samples (based on MD5) in their database.[48]

Over time other companies were founded. In 1996, in Romania, Bitdefender was founded and released the first version of Anti-Virus eXpert (AVX).[49] In 1997, in Russia, Eugene Kaspersky and Natalya Kaspersky co-founded security firm Kaspersky Lab.[50]

In 1996, there was also the first "in the wild" Linux virus, known as "Staog".[51]

In 1999, AV-TEST reported that there were 98,428 unique malware samples (based on MD5) in their database.[48]

2000–2005 period

In 2000, Rainer Link and Howard Fuhs started the first open source antivirus engine, called OpenAntivirus Project.[52]

In 2001, Tomasz Kojm released the first version of ClamAV, the first ever open source antivirus engine to be commercialised. In 2007, ClamAV was bought by Sourcefire,[53] which in turn was acquired by Cisco Systems in 2013.[54]

In 2002, in United Kingdom, Morten Lund and Theis Søndergaard co-founded the antivirus firm BullGuard.[55]

In 2005, AV-TEST reported that there were 333,425 unique malware samples (based on MD5) in their database.[48]

2005–2014 period

In 2007, AV-TEST reported a number of 5,490,960 new unique malware samples (based on MD5) only for that year.[48] In 2012 and 2013, antivirus firms reported a new malware samples range from 300,000 to over 500,000 per day.[56][57]

Over the years it has become necessary for antivirus software to use several different strategies (e.g. specific email and network protection or low level modules) and detection algorithms, as well as to check an increasing variety of files, rather than just executables, for several reasons:

- Powerful macros used in word processor applications, such as Microsoft Word, presented a risk. Virus writers could use the macros to write viruses embedded within documents. This meant that computers could now also be at risk from infection by opening documents with hidden attached macros.[58]

- The possibility of embedding executable objects inside otherwise non-executable file formats can make opening those files a risk.[59]

- Later email programs, in particular Microsoft's Outlook Express and Outlook, were vulnerable to viruses embedded in the email body itself. A user's computer could be infected by just opening or previewing a message.[60]

In 2005, F-Secure was the first security firm that developed an Anti-Rootkit technology, called BlackLight.

Because most users are usually connected to the Internet on a continual basis, Jon Oberheide first proposed a Cloud-based antivirus design in 2008.[61]

In February 2008 McAfee Labs added the industry-first cloud-based anti-malware functionality to VirusScan under the name Artemis. It was tested by AV-Comparatives in February 2008[62] and officially unveiled in August 2008 in McAfee VirusScan.[63]

Cloud AV created problems for comparative testing of security software – part of the AV definitions was out of testers control (on constantly updated AV company servers) thus making results non-repeatable. As a result, Anti-Malware Testing Standards Organisation (AMTSO) started working on method of testing cloud products which was adopted on May 7, 2009.[64]

In 2011, AVG introduced a similar cloud service, called Protective Cloud Technology.[65]

2014–present: rise of next-gen, market consolidation

Following the 2013 release of the APT 1 report from Mandiant, the industry has seen a shift towards signature-less approaches to the problem capable of detecting and mitigating zero-day attacks.[66] Numerous approaches to address these new forms of threats have appeared, including behavioral detection, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and cloud-based file detonation. According to Gartner, it is expected the rise of new entrants, such Carbon Black, Cylance and Crowdstrike will force EPP incumbents into a new phase of innovation and acquisition.[67] One method from Bromium involves micro-virtualization to protect desktops from malicious code execution initiated by the end user. Another approach from SentinelOne and Carbon Black focuses on behavioral detection by building a full context around every process execution path in real time,[68][69] while Cylance leverages an artificial intelligence model based on machine learning.[70] Increasingly, these signature-less approaches have been defined by the media and analyst firms as "next-generation" antivirus[71] and are seeing rapid market adoption as certified antivirus replacement technologies by firms such as Coalfire and DirectDefense.[72] In response, traditional antivirus vendors such as Trend Micro,[73] Symantec and Sophos[74] have responded by incorporating "next-gen" offerings into their portfolios as analyst firms such as Forrester and Gartner have called traditional signature-based antivirus "ineffective" and "outdated".[75]

As of Windows 8, Windows includes its own free antivirus protection under the Windows Defender brand. Despite bad detection scores in its early days, AV-Test now certifies Defender as one of its top products.[76][77] While it isn't publicly known how the inclusion of antivirus software in Windows affected antivirus sales, Google search traffic for antivirus has declined significantly since 2010.[78]

Since 2016, there has been a notable amount of consolidation in the industry. Avast purchased AVG in 2016 for $1.3 billion.[79] Avira was acquired by Norton owner Gen Digital (then NortonLifeLock) in 2020 for $360 million.[80] In 2021, the Avira division of Gen Digital acquired BullGuard.[81] The BullGuard brand was discontinued in 2022 and its customers were migrated to Norton. In 2022, Gen Digital acquired Avast, effectively consolidating four major antivirus brands under one owner.[82]

Identification methods

In 1987, Frederick B. Cohen demonstrated that the algorithm, which would be able to detect all possible viruses, can't possibly exist (like the algorithm which determines whether or not the given program halts).[27] However, using different layers of defense, a good detection rate may be achieved.

There are several methods which antivirus engines can use to identify malware:

- Sandbox detection: a particular behavioural-based detection technique that, instead of detecting the behavioural fingerprint at run time, it executes the programs in a virtual environment, logging what actions the program performs. Depending on the actions logged which can include memory usage and network accesses,[83] the antivirus engine can determine if the program is malicious or not.[84] If not, then, the program is executed in the real environment. Albeit this technique has shown to be quite effective, given its heaviness and slowness, it is rarely used in end-user antivirus solutions.[85]

- Data mining techniques: one of the latest approaches applied in malware detection. Data mining and machine learning algorithms are used to try to classify the behaviour of a file (as either malicious or benign) given a series of file features, that are extracted from the file itself.[86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][excessive citations]

Signature-based detection

Traditional antivirus software relies heavily upon signatures to identify malware.[100]

Substantially, when a malware sample arrives in the hands of an antivirus firm, it is analysed by malware researchers or by dynamic analysis systems. Then, once it is determined to be a malware, a proper signature of the file is extracted and added to the signatures database of the antivirus software.[101]

Although the signature-based approach can effectively contain malware outbreaks, malware authors have tried to stay a step ahead of such software by writing "oligomorphic", "polymorphic" and, more recently, "metamorphic" viruses, which encrypt parts of themselves or otherwise modify themselves as a method of disguise, so as to not match virus signatures in the dictionary.[102]

Heuristics

Many viruses start as a single infection and through either mutation or refinements by other attackers, can grow into dozens of slightly different strains, called variants. Generic detection refers to the detection and removal of multiple threats using a single virus definition.[103]

For example, the Vundo trojan has several family members, depending on the antivirus vendor's classification. Symantec classifies members of the Vundo family into two distinct categories, Trojan.Vundo and Trojan.Vundo.B.[104][105]

While it may be advantageous to identify a specific virus, it can be quicker to detect a virus family through a generic signature or through an inexact match to an existing signature. Virus researchers find common areas that all viruses in a family share uniquely and can thus create a single generic signature. These signatures often contain non-contiguous code, using wildcard characters where differences lie. These wildcards allow the scanner to detect viruses even if they are padded with extra, meaningless code.[106] A detection that uses this method is said to be "heuristic detection".

Rootkit detection

Anti-virus software can attempt to scan for rootkits. A rootkit is a type of malware designed to gain administrative-level control over a computer system without being detected. Rootkits can change how the operating system functions and in some cases can tamper with the anti-virus program and render it ineffective. Rootkits are also difficult to remove, in some cases requiring a complete re-installation of the operating system.[107]

Real-time protection

Real-time protection, on-access scanning, background guard, resident shield, autoprotect, and other synonyms refer to the automatic protection provided by most antivirus, anti-spyware, and other anti-malware programs. This monitors computer systems for suspicious activity such as computer viruses, spyware, adware, and other malicious objects. Real-time protection detects threats in opened files and scans apps in real-time as they are installed on the device.[108] When inserting a CD, opening an email, or browsing the web, or when a file already on the computer is opened or executed.[109]

Issues of concern

Unexpected renewal costs

Some commercial antivirus software end-user license agreements include a clause that the subscription will be automatically renewed, and the purchaser's credit card automatically billed, at the renewal time without explicit approval. For example, McAfee requires users to unsubscribe at least 60 days before the expiration of the present subscription[110] while Bitdefender sends notifications to unsubscribe 30 days before the renewal.[111] Norton AntiVirus also renews subscriptions automatically by default.[112]

Rogue security applications

Some apparent antivirus programs are actually malware masquerading as legitimate software, such as WinFixer, MS Antivirus, and Mac Defender.[113]

Problems caused by false positives

A "false positive" or "false alarm" is when antivirus software identifies a non-malicious file as malware. When this happens, it can cause serious problems. For example, if an antivirus program is configured to immediately delete or quarantine infected files, as is common on Microsoft Windows antivirus applications, a false positive in an essential file can render the Windows operating system or some applications unusable.[114] Recovering from such damage to critical software infrastructure incurs technical support costs and businesses can be forced to close whilst remedial action is undertaken.[115][116]

Examples of serious false-positives:

- May 2007: a faulty virus signature issued by Symantec mistakenly removed essential operating system files, leaving thousands of PCs unable to boot.[117]

- May 2007: the executable file required by Pegasus Mail on Windows was falsely detected by Norton AntiVirus as being a Trojan and it was automatically removed, preventing Pegasus Mail from running. Norton AntiVirus had falsely identified three releases of Pegasus Mail as malware, and would delete the Pegasus Mail installer file when that happened.[118] In response to this Pegasus Mail stated: