Degeneracy (mathematics)

In mathematics, a degenerate case is a limiting case of a class of objects which appears to be qualitatively different from (and usually simpler than) the rest of the class,[1] and the term degeneracy is the condition of being a degenerate case.[2]

The definitions of many classes of composite or structured objects often implicitly include inequalities. For example, the angles and the side lengths of a triangle are supposed to be positive. The limiting cases, where one or several of these inequalities become equalities, are degeneracies. In the case of triangles, one has a degenerate triangle if at least one side length or angle is zero. Equivalently, it becomes a "line segment".[3]

Often, the degenerate cases are the exceptional cases where changes to the usual dimension or the cardinality of the object (or of some part of it) occur. For example, a triangle is an object of dimension two, and a degenerate triangle is contained in a line,[3] which makes its dimension one. This is similar to the case of a circle, whose dimension shrinks from two to zero as it degenerates into a point.[1] As another example, the solution set of a system of equations that depends on parameters generally has a fixed cardinality and dimension, but cardinality and/or dimension may be different for some exceptional values, called degenerate cases. In such a degenerate case, the solution set is said to be degenerate.

For some classes of composite objects, the degenerate cases depend on the properties that are specifically studied. In particular, the class of objects may often be defined or characterized by systems of equations. In most scenarios, a given class of objects may be defined by several different systems of equations, and these different systems of equations may lead to different degenerate cases, while characterizing the same non-degenerate cases. This may be the reason for which there is no general definition of degeneracy, despite the fact that the concept is widely used and defined (if needed) in each specific situation.

A degenerate case thus has special features which makes it non-generic, or a special case. However, not all non-generic or special cases are degenerate. For example, right triangles, isosceles triangles and equilateral triangles are non-generic and non-degenerate. In fact, degenerate cases often correspond to singularities, either in the object or in some configuration space. For example, a conic section is degenerate if and only if it has singular points (e.g., point, line, intersecting lines).[4]

In geometry

Conic section

A degenerate conic is a conic section (a second-degree plane curve, defined by a polynomial equation of degree two) that fails to be an irreducible curve.

- A point is a degenerate circle, namely one with radius 0.[1]

- The line is a degenerate case of a parabola if the parabola resides on a tangent plane. In inversive geometry, a line is a degenerate case of a circle, with infinite radius.

- Two parallel lines also form a degenerate parabola.

- A line segment can be viewed as a degenerate case of an ellipse in which the semiminor axis goes to zero, the foci go to the endpoints, and the eccentricity goes to one.

- A circle can be thought of as a degenerate ellipse, as the eccentricity approaches 0 and the foci merge.[1]

- An ellipse can also degenerate into a single point.

- A hyperbola can degenerate into two lines crossing at a point, through a family of hyperbolae having those lines as common asymptotes.

Triangle

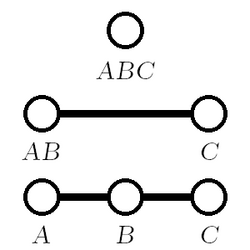

- A degenerate triangle has collinear vertices[3] and zero area, and thus coincides with a segment covered twice (if the three vertices are not all equal; otherwise, the triangle degenerates to a single point). If the three vertices are pairwise distinct, it has two 0° angles and one 180° angle. If two vertices are equal, it has one 0° angle and two undefined angles.

Rectangle

- A line segment is a degenerate case of a rectangle which has a side of length 0.

- For any non-empty subset , there is a bounded, axis-aligned degenerate rectangle where and ai, bi, ci are constant (with ai ≤ bi for all i). The number of degenerate sides of R is the number of elements of the subset S. Thus, there may be as few as one degenerate "side" or as many as n (in which case R reduces to a singleton point).

Convex polygon

- A convex polygon is degenerate if at least two consecutive sides coincide at least partially, or at least one side has zero length, or at least one angle is 180°. Thus a degenerate convex polygon of n sides looks like a polygon with fewer sides. In the case of triangles, this definition coincides with the one that has been given above.

Convex polyhedron

- A convex polyhedron is degenerate if either two adjacent facets are coplanar or two edges are aligned. In the case of a tetrahedron, this is equivalent to saying that all of its vertices lie in the same plane, giving it a volume of zero.

Standard torus

- In contexts where self-intersection is allowed, a double-covered sphere is a degenerate standard torus where the axis of revolution passes through the center of the generating circle, rather than outside it.

- A torus degenerates to a circle when its minor radius goes to 0.

Sphere

- When the radius of a sphere goes to zero, the resulting degenerate sphere of zero volume is a point.

Other

- See general position for other examples.

Elsewhere

- A set containing a single point is a degenerate continuum.

- Objects such as the digon and monogon can be viewed as degenerate cases of polygons: valid in a general abstract mathematical sense, but not part of the original Euclidean conception of polygons.

- A random variable which can only take one value has a degenerate distribution; if that value is the real number 0, then its probability density is the Dirac delta function.

- A root of a polynomial is sometimes said to be degenerate if it is a multiple root, since generically the n roots of an nth degree polynomial are all distinct.[1] This usage carries over to eigenproblems: a degenerate eigenvalue is a multiple root of the characteristic polynomial.

- In quantum mechanics, any such multiplicity in the eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian operator gives rise to degenerate energy levels. Usually any such degeneracy indicates some underlying symmetry in the system.

See also

- Degeneracy (graph theory)

- Degenerate form

- Trivial (mathematics)

- Pathological (mathematics)

- Vacuous truth

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weisstein, Eric W.. "Degenerate" (in en). http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Degenerate.html.

- ↑ "Definition of DEGENERACY" (in en). https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/degeneracy.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Mathwords: Degenerate". https://www.mathwords.com/d/degenerate.htm.

- ↑ "Mathwords: Degenerate Conic Sections". https://www.mathwords.com/d/degenerate_conics.htm.

|