Pathological (mathematics)

In mathematics, when a mathematical phenomenon runs counter to some intuition, then the phenomenon is sometimes called pathological. On the other hand, if a phenomenon does not run counter to intuition, it is sometimes called well-behaved. These terms are sometimes useful in mathematical research and teaching, but there is no strict mathematical definition of pathological or well-behaved.[1]

In analysis

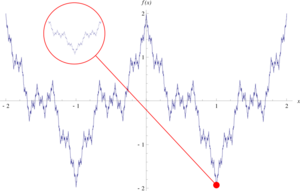

A classic example of a pathology is the Weierstrass function, a function that is continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere.[1] The sum of a differentiable function and the Weierstrass function is again continuous but nowhere differentiable; so there are at least as many such functions as differentiable functions. In fact, using the Baire category theorem, one can show that continuous functions are generically nowhere differentiable.[2]

Such examples were deemed pathological when they were first discovered: To quote Henri Poincaré:[3]

Logic sometimes breeds monsters. For half a century there has been springing up a host of weird functions, which seem to strive to have as little resemblance as possible to honest functions that are of some use. No more continuity, or else continuity but no derivatives, etc. More than this, from the point of view of logic, it is these strange functions that are the most general; those that are met without being looked for no longer appear as more than a particular case, and they have only quite a little corner left them.

Formerly, when a new function was invented, it was in view of some practical end. To-day they are invented on purpose to show our ancestors' reasonings at fault, and we shall never get anything more than that out of them.

If logic were the teacher's only guide, he would have to begin with the most general, that is to say, with the most weird, functions. He would have to set the beginner to wrestle with this collection of monstrosities. If you don't do so, the logicians might say, you will only reach exactness by stages.

— Henri Poincaré, Science and Method (1899), (1914 translation), page 125

Since Poincaré, nowhere differentiable functions have been shown to appear in basic physical and biological processes such as Brownian motion and in applications such as the Black-Scholes model in finance.

Counterexamples in Analysis is a whole book of such counterexamples.[4]

In topology

One famous counterexample in topology is the Alexander horned sphere, showing that topologically embedding the sphere S2 in R3 may fail to separate the space cleanly. As a counterexample, it motivated mathematicians to define the tameness property, which suppresses the kind of wild behavior exhibited by the horned sphere, wild knot, and other similar examples.[5]

Like many other pathologies, the horned sphere in a sense plays on infinitely fine, recursively generated structure, which in the limit violates ordinary intuition. In this case, the topology of an ever-descending chain of interlocking loops of continuous pieces of the sphere in the limit fully reflects that of the common sphere, and one would expect the outside of it, after an embedding, to work the same. Yet it does not: it fails to be simply connected.

For the underlying theory, see Jordan–Schönflies theorem.

Counterexamples in Topology is a whole book of such counterexamples.[6]

Well-behaved

Mathematicians (and those in related sciences) very frequently speak of whether a mathematical object—a function, a set, a space of one sort or another—is "well-behaved". While the term has no fixed formal definition, it generally refers to the quality of satisfying a list of prevailing conditions, which might be dependent on context, mathematical interests, fashion, and taste. To ensure that an object is "well-behaved", mathematicians introduce further axioms to narrow down the domain of study. This has the benefit of making analysis easier, but produces a loss of generality of any conclusions reached.

In both pure and applied mathematics (e.g., optimization, numerical integration, mathematical physics), well-behaved also means not violating any assumptions needed to successfully apply whatever analysis is being discussed.

The opposite case is usually labeled "pathological". It is not unusual to have situations in which most cases (in terms of cardinality or measure) are pathological, but the pathological cases will not arise in practice—unless constructed deliberately.

The term "well-behaved" is generally applied in an absolute sense—either something is well-behaved or it is not. For example:

- In algorithmic inference, a well-behaved statistic is monotonic, well-defined, and sufficient.

- In Bézout's theorem, two polynomials are well-behaved, and thus the formula given by the theorem for the number of their intersections is valid, if their polynomial greatest common divisor is a constant.

- A meromorphic function is a ratio of two well-behaved functions, in the sense of those two functions being holomorphic.

- The Karush–Kuhn–Tucker conditions are first-order necessary conditions for a solution in a well-behaved nonlinear programming problem to be optimal; a problem is referred to as well-behaved if some regularity conditions are satisfied.

- In probability, events contained in the probability space's corresponding sigma-algebra are well-behaved, as are measurable functions.

Unusually, the term could also be applied in a comparative sense:

- In calculus:

- Analytic functions are better-behaved than general smooth functions.

- Smooth functions are better-behaved than general differentiable functions.

- Continuous differentiable functions are better-behaved than general continuous functions. The larger the number of times the function can be differentiated, the more well-behaved it is.

- Continuous functions are better-behaved than Riemann-integrable functions on compact sets.

- Riemann-integrable functions are better-behaved than Lebesgue-integrable functions.

- Lebesgue-integrable functions are better-behaved than general functions.

- In topology, continuous functions are better-behaved than discontinuous ones.

- Euclidean space is better-behaved than non-Euclidean geometry.

- Attractive fixed points are better-behaved than repulsive fixed points.

- Hausdorff topologies are better-behaved than those in arbitrary general topology.

- Borel sets are better-behaved than arbitrary sets of real numbers.

- Spaces with integer dimension are better-behaved than spaces with fractal dimension.

- In abstract algebra:

- Groups are better-behaved than magmas and semigroups.

- Abelian groups are better-behaved than non-Abelian groups.

- Finitely-generated Abelian groups are better-behaved than non-finitely-generated Abelian groups.

- Finite-dimensional vector spaces are better-behaved than infinite-dimensional ones.

- Fields are better-behaved than skew fields or general rings.

- Separable field extensions are better-behaved than non-separable ones.

- Normed division algebras are better-behaved than general composition algebras.

Pathological examples

Pathological examples often have some undesirable or unusual properties that make it difficult to contain or explain within a theory. Such pathological behaviors often prompt new investigation and research, which leads to new theory and more general results. Some important historical examples of this are:

- The discovery of irrational numbers by the school of Pythagoras in ancient Greece; for example, the length of the diagonal of a unit square, that is .

- The discovery of complex numbers in the 16th century in order to find the roots of cubic and quartic polynomial functions.

- Some number fields have rings of integers that do not form a unique factorization domain, for example the extended field .

- The discovery of fractals and other "rough" geometric objects (see Hausdorff dimension).

- Weierstrass function, a real-valued function on the real line, that is continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere.[1]

- Test functions in real analysis and distribution theory, which are infinitely differentiable functions on the real line that are 0 everywhere outside of a given limited interval. An example of such a function is the test function,

- The Cantor set is a subset of the interval that has measure zero but is uncountable.

- The fat Cantor set is nowhere dense but has positive measure.

- The Fabius function is everywhere smooth but nowhere analytic.

- Volterra's function is differentiable with bounded derivative everywhere, but the derivative is not Riemann-integrable.

- The Peano space-filling curve is a continuous surjective function that maps the unit interval onto .

- The Dirichlet function, which is the indicator function for rationals, is a bounded function that is not Riemann integrable.

- The Cantor function is a monotonic continuous surjective function that maps onto , but has zero derivative almost everywhere.

- The Minkowski question-mark function is continuous and strictly increasing but has zero derivative almost everywhere.

- Satisfaction classes containing "intuitively false" arithmetical statements can be constructed for countable, recursively saturated models of Peano arithmetic. [citation needed]

- The Osgood curve is a Jordan curve (unlike most space-filling curves) of positive area.

- An exotic sphere is homeomorphic but not diffeomorphic to the standard Euclidean n-sphere.

At the time of their discovery, each of these was considered highly pathological; today, each has been assimilated into modern mathematical theory. These examples prompt their observers to correct their beliefs or intuitions, and in some cases necessitate a reassessment of foundational definitions and concepts. Over the course of history, they have led to more correct, more precise, and more powerful mathematics. For example, the Dirichlet function is Lebesgue integrable, and convolution with test functions is used to approximate any locally integrable function by smooth functions.[Note 1]

Whether a behavior is pathological is by definition subject to personal intuition. Pathologies depend on context, training, and experience, and what is pathological to one researcher may very well be standard behavior to another.

Pathological examples can show the importance of the assumptions in a theorem. For example, in statistics, the Cauchy distribution does not satisfy the central limit theorem, even though its symmetric bell-shape appears similar to many distributions which do; it fails the requirement to have a mean and standard deviation which exist and that are finite.

Some of the best-known paradoxes, such as Banach–Tarski paradox and Hausdorff paradox, are based on the existence of non-measurable sets. Mathematicians, unless they take the minority position of denying the axiom of choice, are in general resigned to living with such sets.[citation needed]

Computer science

In computer science, pathological has a slightly different sense with regard to the study of algorithms. Here, an input (or set of inputs) is said to be pathological if it causes atypical behavior from the algorithm, such as a violation of its average case complexity, or even its correctness. For example, hash tables generally have pathological inputs: sets of keys that collide on hash values. Quicksort normally has time complexity, but deteriorates to when it is given input that triggers suboptimal behavior.

The term is often used pejoratively, as a way of dismissing such inputs as being specially designed to break a routine that is otherwise sound in practice (compare with Byzantine). On the other hand, awareness of pathological inputs is important, as they can be exploited to mount a denial-of-service attack on a computer system. Also, the term in this sense is a matter of subjective judgment as with its other senses. Given enough run time, a sufficiently large and diverse user community (or other factors), an input which may be dismissed as pathological could in fact occur (as seen in the first test flight of the Ariane 5).

Exceptions

A similar but distinct phenomenon is that of exceptional objects (and exceptional isomorphisms), which occurs when there are a "small" number of exceptions to a general pattern (such as a finite set of exceptions to an otherwise infinite rule). By contrast, in cases of pathology, often most or almost all instances of a phenomenon are pathological (e.g., almost all real numbers are irrational).

Subjectively, exceptional objects (such as the icosahedron or sporadic simple groups) are generally considered "beautiful", unexpected examples of a theory, while pathological phenomena are often considered "ugly", as the name implies. Accordingly, theories are usually expanded to include exceptional objects. For example, the exceptional Lie algebras are included in the theory of semisimple Lie algebras: the axioms are seen as good, the exceptional objects as unexpected but valid.

By contrast, pathological examples are instead taken to point out a shortcoming in the axioms, requiring stronger axioms to rule them out. For example, requiring tameness of an embedding of a sphere in the Schönflies problem. In general, one may study the more general theory, including the pathologies, which may provide its own simplifications (the real numbers have properties very different from the rationals, and likewise continuous maps have very different properties from smooth ones), but also the narrower theory, from which the original examples were drawn.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weisstein, Eric W.. "Pathological" (in en). http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Pathological.html.

- ↑ "Baire Category & Nowhere Differentiable Functions (Part One)". https://www.math3ma.com/blog/baire-category-nowhere-differentiable-functions-part-one.

- ↑ Kline, Morris (1990). Mathematical thought from ancient to modern times.. Oxford University Press. pp. 973. OCLC 1243569759. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1243569759.

- ↑ Gelbaum, Bernard R. (1964). Counterexamples in analysis. John M. H. Olmsted. San Francisco: Holden-Day. ISBN 0-486-42875-3. OCLC 527671. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/527671.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W.. "Alexander's Horned Sphere" (in en). http://mathworld.wolfram.com/AlexandersHornedSphere.html.

- ↑ Steen, Lynn Arthur (1995). Counterexamples in topology. J. Arthur Seebach. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-68735-X. OCLC 32311847. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/32311847.

Notes

- ↑ The approximations converge almost everywhere and in the space of locally integrable functions.

External links

- Pathological Structures & Fractals – Extract of an article by Freeman Dyson, "Characterising Irregularity", Science, May 1978

|