Earth:Constructed wetland

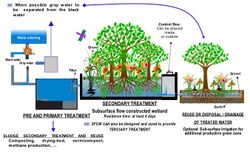

A constructed wetland is an artificial wetland to treat sewage, greywater, stormwater runoff or industrial wastewater.[1][2] It may also be designed for land reclamation after mining, or as a mitigation step for natural areas lost to land development. Constructed wetlands are engineered systems that use the natural functions of vegetation, soil, and organisms to provide secondary treatment to wastewater. The design of the constructed wetland has to be adjusted according to the type of wastewater to be treated. Constructed wetlands have been used in both centralized and decentralized wastewater systems. Primary treatment is recommended when there is a large amount of suspended solids or soluble organic matter (measured as biochemical oxygen demand and chemical oxygen demand).[3]

Similar to natural wetlands, constructed wetlands also act as a biofilter and/or can remove a range of pollutants (such as organic matter, nutrients, pathogens, heavy metals) from the water. Constructed wetlands are designed to remove water pollutants such as suspended solids, organic matter and nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus).[3] All types of pathogens (i.e., bacteria, viruses, protozoans and helminths) are expected to be removed to some extent in a constructed wetland. Subsurface wetlands provide greater pathogen removal than surface wetlands.[3]

There are two main types of constructed wetlands: subsurface flow and surface flow. The planted vegetation plays an important role in contaminant removal. The filter bed, consisting usually of sand and gravel, has an equally important role to play.[4] Some constructed wetlands may also serve as a habitat for native and migratory wildlife, although that is not their main purpose. Subsurface flow constructed wetlands are designed to have either horizontal flow or vertical flow of water through the gravel and sand bed. Vertical flow systems have a smaller space requirement than horizontal flow systems.

Terminology

Many terms are used to denote constructed wetlands, such as reed beds, soil infiltration beds, treatment wetlands, engineered wetlands, man-made or artificial wetlands.[4] A biofilter has some similarities with a constructed wetland, but is usually without plants.

The term of constructed wetlands can also be used to describe restored and recultivated land that was destroyed in the past through draining and converting into farmland, or mining.

Overview

A constructed wetland is an engineered sequence of water bodies designed to treat wastewater or storm water runoff.

Vegetation in a wetland provides a substrate (roots, stems, and leaves) upon which microorganisms can grow as they break down organic materials. This community of microorganisms is known as the periphyton. The periphyton and natural chemical processes are responsible for approximately 90 percent of pollutant removal and waste breakdown.[5] The plants remove about seven to ten percent of pollutants, and act as a carbon source for the microbes when they decay. Different species of aquatic plants have different rates of heavy metal uptake, a consideration for plant selection in a constructed wetland used for water treatment. Constructed wetlands are of two basic types: subsurface flow and surface flow wetlands.

Constructed wetlands are one example of nature-based solutions and of phytoremediation.

Constructed wetland systems are highly controlled environments that intend to mimic the occurrences of soil, flora, and microorganisms in natural wetlands to aid in treating wastewater. They are constructed with flow regimes, micro-biotic composition, and suitable plants in order to produce the most efficient treatment process.

Uses

Constructed wetlands can be used to treat raw sewage, storm water, agricultural and industrial effluent. Constructed wetlands mimic the functions of natural wetlands to capture stormwater, reduce nutrient loads, and create diverse wildlife habitat. Constructed wetlands are used for wastewater treatment or for greywater treatment.[6]

Many regulatory agencies list treatment wetlands as one of their recommended "best management practices" for controlling urban runoff.[7]

Removal of contaminants

Physical, chemical, and biological processes combine in wetlands to remove contaminants from wastewater. An understanding of these processes is fundamental not only to designing wetland systems but to understanding the fate of chemicals once they enter the wetland. Theoretically, wastewater treatment within a constructed wetland occurs as it passes through the wetland medium and the plant rhizosphere. A thin film around each root hair is aerobic due to the leakage of oxygen from the rhizomes, roots, and rootlets.[8] Aerobic and anaerobic micro-organisms facilitate decomposition of organic matter. Microbial nitrification and subsequent denitrification releases nitrogen as gas to the atmosphere. Phosphorus is coprecipitated with iron, aluminium, and calcium compounds located in the root-bed medium.[8][9] Suspended solids filter out as they settle in the water column in surface flow wetlands or are physically filtered out by the medium within subsurface flow wetlands. Harmful bacteria, fungi, and viruses are reduced by filtration and adsorption by biofilms on the gravel or sand media in subsurface flow and vertical flow systems.[citation needed]

Nitrogen removal

The dominant forms of nitrogen in wetlands that are of importance to wastewater treatment include organic nitrogen, ammonia, ammonium, nitrate and nitrite. Total nitrogen refers to all nitrogen species. Wastewater nitrogen removal is important because of ammonia's toxicity to fish if discharged into watercourses. Excessive nitrates in drinking water is thought to cause methemoglobinemia in infants, which decreases the blood's oxygen transport ability. Moreover, excess input of N from point and non-point sources to surface water promotes eutrophication in rivers, lakes, estuaries, and coastal oceans which causes several problems in aquatic ecosystems e.g. toxic algal blooms, oxygen depletion in water, fish mortality, loss of aquatic biodiversity.[10]

Ammonia removal occurs in constructed wetlands – if they are designed to achieve biological nutrient removal – in a similar ways as in sewage treatment plants, except that no external, energy-intensive addition of air (oxygen) is needed.[6] It is a two-step process, consisting of nitrification followed by denitrification. The nitrogen cycle is completed as follows: ammonia in the wastewater is converted to ammonium ions; the aerobic bacterium Nitrosomonas sp. oxidizes ammonium to nitrite; the bacterium Nitrobacter sp. then converts nitrite to nitrate. Under anaerobic conditions, nitrate is reduced to relatively harmless nitrogen gas that enters the atmosphere.[citation needed]

Nitrification

Nitrification is the biological conversion of organic and inorganic nitrogenous compounds from a reduced state to a more oxidized state, based on the action of two different bacteria types.[11] Nitrification is strictly an aerobic process in which the end product is nitrate (NO−3). The process of nitrification oxidizes ammonium (from the wastewater) to nitrite (NO−2), and then nitrite is oxidized to nitrate (NO−3).

Denitrification

Denitrification is the biochemical reduction of oxidized nitrogen anions, nitrate and nitrite to produce the gaseous products nitric oxide (NO), nitrous oxide (N2O) and nitrogen gas (N2), with concomitant oxidation of organic matter.[11] The end product, N2, and to a lesser extent the intermediary by product, N2O, are gases that re-enter the atmosphere.

Ammonia removal from mine water

Constructed wetlands have been used to remove ammonia and other nitrogenous compounds from contaminated mine water,[12] including cyanide and nitrate.

Phosphorus removal

Phosphorus occurs naturally in both organic and inorganic forms. The analytical measure of biologically available orthophosphates is referred to as soluble reactive phosphorus (SR-P). Dissolved organic phosphorus and insoluble forms of organic and inorganic phosphorus are generally not biologically available until transformed into soluble inorganic forms.[13]

In freshwater aquatic ecosystems phosphorus is typically the major limiting nutrient. Under undisturbed natural conditions, phosphorus is in short supply. The natural scarcity of phosphorus is demonstrated by the explosive growth of algae in water receiving heavy discharges of phosphorus-rich wastes. Because phosphorus does not have an atmospheric component, unlike nitrogen, the phosphorus cycle can be characterized as closed. The removal and storage of phosphorus from wastewater can only occur within the constructed wetland itself. Phosphorus may be sequestered within a wetland system by:

- The binding of phosphorus in organic matter as a result of incorporation into living biomass,

- Precipitation of insoluble phosphates with ferric iron, calcium, and aluminium found in wetland soils.[13]

Biomass plants incorporation

Aquatic vegetation may play an important role in phosphorus removal and, if harvested, extend the life of a system by postponing phosphorus saturation of the sediments.[14] Plants create a unique environment at the biofilm's attachment surface. Certain plants transport oxygen which is released at the biofilm/root interface, adding oxygen to the wetland system. Plants also increase soil or other root-bed medium hydraulic conductivity. As roots and rhizomes grow they are thought to disturb and loosen the medium, increasing its porosity, which may allow more effective fluid movement in the rhizosphere. When roots decay they leave behind ports and channels known as macropores which are effective in channeling water through the soil.

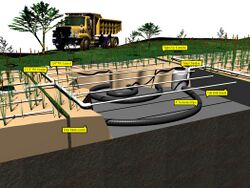

Metals removal

Constructed wetlands have been used extensively for the removal of dissolved metals and metalloids. Although these contaminants are prevalent in mine drainage, they are also found in stormwater, landfill leachate and other sources (e.g., leachate or FDG washwater[citation needed] at coal-fired power plants), for which treatment wetlands have been constructed for mines.[15]

Mine water—Acid drainage removal

Constructed wetlands can also be used for treatment of acid mine drainage from coal mines.[16]

Pathogen removal

Constructed wetlands are not designed for pathogen removal, but have been designed to remove other water quality constituents such as suspended solids, organic matter (biochemical oxygen demand and chemical oxygen demand) and nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus).[3]

All types of pathogens are expected to be removed in a constructed wetland; however, greater pathogen removal is expected to occur in a subsurface wetland. In a free water surface flow wetland one can expect 1 to 2 log10 reduction of pathogens; however, bacteria and virus removal may be less than 1 log10 reduction in systems that are heavily planted with vegetation.[3] This is because constructed wetlands typically include vegetation which assists in removing other pollutants such as nitrogen and phosphorus. Therefore, the importance of sunlight exposure in removing viruses and bacteria is minimized in these systems.[3]

Removal in a properly designed and operated free water surface flow wetland is reported to be less than 1 to 2 log10 for bacteria, less than 1 to 2 log10 for viruses, 1 to 2 log10 for protozoa, and 1 to 2 log10 for helminths.[3] In subsurface flow wetlands, the expected removal of pathogens is reported to be 1 to 3 log10 for bacteria, 1 to 2 log10 for viruses, 2 log10 for protozoa, and 2 log10 for helminths.[3]

The log10 removal efficiencies reported here can also be understood in terms of the common way of reporting removal efficiencies as percentages: 1 log10 removal is equivalent to a removal efficiency of 90%; 2 log10 = 99%; 3 log10 = 99.9%; 4 log10 = 99.99% and so on.[6]

Types and design considerations

Constructed wetland systems can be surface flow systems with only free-floating macrophytes, floating-leaved macrophytes, or submerged macrophytes; however, typical free water surface systems are usually constructed with emergent macrophytes.[17] Subsurface flow-constructed wetlands with a vertical or a horizontal flow regime are also common and can be integrated into urban areas as they require relatively little space.[4]

The main three broad types of constructed wetlands include:[18][6]

- Subsurface flow constructed wetland – this wetland can be either with vertical flow (the effluent moves vertically, from the planted layer down through the substrate and out) or with horizontal flow (the effluent moves horizontally, parallel to the surface)

- Surface flow constructed wetland (this wetland has horizontal flow)

- Floating treatment wetland

The former types are placed in a basin with a substrate to provide a surface area upon which large amounts of waste degrading biofilms form, while the latter relies on a flooded treatment basin upon which aquatic plants are held in flotation till they develop a thick mat of roots and rhizomes upon which biofilms form. In most cases, the bottom is lined with either a polymer geomembrane, concrete or clay (when there is appropriate clay type) in order to protect the water table and surrounding grounds. The substrate can be either gravel—generally limestone or pumice/volcanic rock, depending on local availability, sand or a mixture of various sizes of media (for vertical flow constructed wetlands).[citation needed]

Constructed wetlands can be used after a septic tank for primary treatment (or other types of systems) in order to separate the solids from the liquid effluent. Some constructed wetland designs however do not use upfront primary treatment.

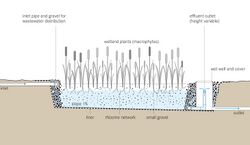

Subsurface flow

In subsurface flow constructed wetlands the flow of wastewater occurs between the roots of the plants and there is no water surfacing (it is kept below gravel). As a result, the system is more efficient, does not attract mosquitoes, is less odorous and less sensitive to winter conditions. Also, less area is needed to purify water. A downside to the system are the intakes, which can clog or bioclog easily, although some larger sized gravel will often solve this problem.

Subsurface flow wetlands can be further classified as horizontal flow or vertical flow constructed wetlands. In the vertical flow constructed wetland, the effluent moves vertically from the planted layer down through the substrate and out (requiring air pumps to aerate the bed).[20] In the horizontal flow constructed wetland the effluent moves horizontally via gravity, parallel to the surface, with no surface water thus avoiding mosquito breeding. Vertical flow constructed wetlands are considered to be more efficient with less area required compared to horizontal flow constructed wetlands. However, they need to be interval-loaded and their design requires more know-how while horizontal flow constructed wetlands can receive wastewater continuously and are easier to build.[4]

Due to the increased efficiency a vertical flow subsurface constructed wetland requires only about 3 square metres (32 sq ft) of space per person equivalent, down to 1.5 square metres in hot climates.[4]

The "French System" combines primary and secondary treatment of raw wastewater. The effluent passes various filter beds whose grain size is getting progressively smaller (from gravel to sand).[4]

Applications

Subsurface flow wetlands can treat a variety of different wastewaters, such as household wastewater, agricultural, paper mill wastewater, mining runoff, tannery or meat processing wastes, storm water.[6]

The quality of the effluent is determined by the design and should be customized for the intended reuse application (like irrigation or toilet flushing) or the disposal method.

Design considerations

Depending on the type of constructed wetlands, the wastewater passes through a gravel and more rarely sand medium on which plants are rooted.[6] A gravel medium (generally limestone or volcanic rock lavastone) can be used as well (the use of lavastone will allow for a surface reduction of about 20% over limestone) is mainly deployed in horizontal flow systems though it does not work as efficiently as sand (but sand will clog more readily).[4]

Constructed subsurface flow wetlands are meant as secondary treatment systems which means that the effluent needs to first pass a primary treatment which effectively removes solids. Such a primary treatment can consist of sand and grit removal, grease trap, compost filter, septic tank, Imhoff tank, anaerobic baffled reactor or upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor.[4] The following treatment is based on different biological and physical processes like filtration, adsorption or nitrification. Most important is the biological filtration through a biofilm of aerobic or facultative bacteria. Coarse sand in the filter bed provides a surfaces for microbial growth and supports the adsorption and filtration processes. For those microorganisms the oxygen supply needs to be sufficient.

Especially in warm and dry climates the effects of evapotranspiration and precipitation are significant. In cases of water loss, a vertical flow constructed wetland is preferable to a horizontal because of an unsaturated upper layer and a shorter retention time, although vertical flow systems are more dependent on an external energy source. Evapotranspiration (as is rainfall) is taken into account in designing a horizontal flow system.[6]

The effluent can have a yellowish or brownish colour if domestic wastewater or blackwater is treated. Treated greywater usually does not tend to have a colour. Concerning pathogen levels, treated greywater meets the standards of pathogen levels for safe discharge to surface water.[3] Treated domestic wastewater might need a tertiary treatment, depending on the intended reuse application.[4]

Plantings of reedbeds are popular in European constructed subsurface flow wetlands, although at least twenty other plant species are usable. Many fast growing timer plants can be used, as well for example as Musa spp., Juncus spp., cattails (Typha spp.) and sedges.

Operation and maintenance

Overloading peaks should not cause performance problems while continuous overloading lead to a loss of treatment capacity through too much suspended solids, sludge or fats.

Subsurface flow wetlands require the following maintenance tasks: regular checking of the pretreatment process, of pumps when they are used, of influent loads and distribution on the filter bed.[4]

Comparisons with other types

Subsurface wetlands are less hospitable to mosquitoes compared to surface flow wetlands, as there is no water exposed to the surface. Mosquitos can be a problem in surface flow constructed wetlands. Subsurface flow systems have the advantage of requiring less land area for water treatment than surface flow. However, surface flow wetlands can be more suitable for wildlife habitat.

For urban applications the area requirement of a subsurface flow constructed wetland might be a limiting factor compared to conventional municipal wastewater treatment plants. High rate aerobic treatment processes like activated sludge plants, trickling filters, rotating discs, submerged aerated filters or membrane bioreactor plants require less space. The advantage of subsurface flow constructed wetlands compared to those technologies is their operational robustness which is particularly important in developing countries. The fact that constructed wetlands do not produce secondary sludge (sewage sludge) is another advantage as there is no need for sewage sludge treatment.[4] However, primary sludge from primary settling tanks does get produced and needs to be removed and treated.

Costs

The costs of subsurface flow constructed wetlands mainly depend on the costs of sand with which the bed has to be filled.[6] Another factor is the cost of land.

Surface flow

Surface flow wetlands, also known as free water surface constructed wetlands, can be used for tertiary treatment or polishing of effluent from wastewater treatment plants.[21] They are also suitable to treat stormwater drainage.

Surface flow constructed wetlands always have horizontal flow of wastewater across the roots of the plants, rather than vertical flow. They require a relatively large area to purify water compared to subsurface flow constructed wetlands and may have increased smell and lower performance in winter.

Surface flow wetlands have a similar appearance to ponds for wastewater treatment (such as "waste stabilization ponds") but are in the technical literature not classified as ponds.[22]

Pathogens are destroyed by natural decay, predation from higher organisms, sedimentation and UV irradiation since the water is exposed to direct sunlight.[3] The soil layer below the water is anaerobic but the roots of the plants release oxygen around them, this allows complex biological and chemical reactions.[23]

Surface flow wetlands can be supported by a wide variety of soil types including bay mud and other silty clays.

Plants such as water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) and Pontederia spp. are used worldwide (although Typha and Phragmites are highly invasive).

However, surface flow constructed wetlands may encourage mosquito breeding. They may also have high algae production that lowers the effluent quality and due to open water surface mosquitos and odours, it is more difficult to integrate them in an urban neighbourhood.

-

Newly planted constructed wetland

-

Same constructed wetland, two years later

Hybrid systems

A combination of different types of constructed wetlands is possible to use the specific advantages of each system.[4]

Integrated constructed wetland

An integrated constructed wetland is an unlined free surface flow constructed wetland with emergent vegetated areas and local soil material. Its objectives is not only to treat wastewater from farmyards and other wastewater sources, but also to integrate the wetland infrastructure into the landscape and enhancing its biological diversity.[24]

Integrated constructed wetland facilitates may be more robust treatment systems compared to other constructed wetlands.[25][26][24] This is due to the greater biological complexity and generally relatively larger land area use and associated longer hydraulic residence time of integrated constructed wetland compared to conventional constructed wetlands.[27]

Integrated constructed wetlands are used in Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States since about 2007. Farm constructed wetlands, which are a subtype of integrated constructed wetlands, are promoted by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency and the Northern Ireland Environment Agency since 2008.[27]

Other design aspects

The design of a constructed wetland can greatly effect the surrounding environment. A wide range of skills and knowledge is needed in the construction and can easily be detrimental to the site if not done correctly. A long list of professions ranging from civil engineers to hydrologists to wildlife biologists to landscape architects are needed in this design process. The landscape architect can utilize a wide range of skills to help accomplish the task of constructing a wetland that may not be thought of by other professions. Ecological landscape architects are also qualified to create wetland restoration designs in coordination with wetland scientists that increase the community value and appreciation of a project through well designed access, interpretation, and views of the project.[28] Landscape architecture has a long history of engagement with the aesthetic dimension of wetlands. Landscape architects also guide through the laws and regulations associated with constructing a wetland.[29]

Plants and other organisms

Plants

Typhas and Phragmites are the main species used in constructed wetland due to their effectiveness, even though they can be invasive outside their native range.

In North America, cattails (Typha latifolia) are common in constructed wetlands because of their widespread abundance, ability to grow at different water depths, ease of transport and transplantation, and broad tolerance of water composition (including pH, salinity, dissolved oxygen and contaminant concentrations). Elsewhere, Common Reed (Phragmites australis) are common (both in blackwater treatment but also in greywater treatment systems to purify wastewater).

Plants are usually indigenous in that location for ecological reasons and optimum workings.

-

Newly planted constructed wetland for blackwater treatment (Lima, Peru)

-

The large roots of this uprooted plant growing in a constructed wetlands indicate a healthy plant (Lima, Peru)

-

A hybrid system using Flowforms in a treatment pond, in Norway .

Animals

Locally grown non-predatory fish can be added to surface flow constructed wetlands to eliminate or reduce pests, such as mosquitos.

Stormwater wetlands provide habitat for amphibians but the pollutants they accumulate can affect the survival of larval stages, potentially making them function as "ecological traps".[30]

Costs

Since constructed wetlands are self-sustaining their lifetime costs are significantly lower than those of conventional treatment systems. Often their capital costs are also lower compared to conventional treatment systems.[31] They do take up significant space, and are therefore not preferred where real estate costs are high.

History

Primary clarifier effluent was discharged directly to natural wetlands for decades before environmental regulations discouraged the practice.[citation needed] Subsurface flow constructed wetlands with sand filter beds have their origin in China and are now used in Asia in small cities.[4]

Examples

Austria

The total number of constructed wetlands in Austria is 5,450 (in 2015).[32] Due to legal requirements (nitrification), only vertical flow constructed wetlands are implemented in Austria as they achieve better nitrification performance than horizontal flow constructed wetlands. Only about 100 of these constructed wetlands have a design size of 50 population equivalents or more. The remaining 5,350 treatment plants are smaller than that.[32]

Canada

As part of the remediation efforts to remove contamination from CFB Goose Bay, one of the waste dumps was transformed into an engineered wetland. [33]

See also

- Decentralized wastewater system

- Ecological engineering

- Ecological sanitation

- Floodplain restoration

- Integrated constructed wetland

- Passive treatment system

- Sanitation

- Vegetative treatment system

- Water-sensitive urban design

- Wetland classification

- Wetlands Construídos (a company in Brazil)

References

- ↑ Vymazal, Jan; Zhao, Yaqian; Mander, Ülo (2021-11-01). "Recent research challenges in constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment: A review" (in en). Ecological Engineering 169: 106318. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2021.106318. ISSN 0925-8574. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925857421001737.

- ↑ Arden, S.; Ma, X. (2018-07-15). "Constructed wetlands for greywater recycle and reuse: A review" (in en). Science of the Total Environment 630: 587–599. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.218. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 29494968. Bibcode: 2018ScTEn.630..587A.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 Maiga, Y., von Sperling, M., Mihelcic, J. 2017. Constructed Wetlands. In: J.B. Rose and B. Jiménez-Cisneros, (eds) Global Water Pathogens Project. (C. Haas, J.R. Mihelcic and M.E. Verbyla) (eds) Part 4 Management Of Risk from Excreta and Wastewater) Michigan State University, E. Lansing, MI, UNESCO.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Hoffmann, H., Platzer, C., von Münch, E., Winker, M. (2011): Technology review of constructed wetlands – Subsurface flow constructed wetlands for greywater and domestic wastewater treatment. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Eschborn, Germany

- ↑ Abdelhakeem, Sara G.; Aboulroos, Samir A.; Kamel, Mohamed M. (2016-09-01). "Performance of a vertical subsurface flow constructed wetland under different operational conditions" (in en). Journal of Advanced Research 7 (5): 803–814. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2015.12.002. ISSN 2090-1232.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Dotro, G.; Langergraber, G.; Molle, P.; Nivala, J.; Puigagut Juárez, J.; Stein, O. R.; von Sperling, M. (2017). "Treatment wetlands". Volume 7. Biological Wastewater Treatment Series. London: IWA Publishing. ISBN 9781780408767. OCLC 984563578. https://www.iwapublishing.com/open-access-ebooks/3567.

- ↑ For example, see Urban Drainage and Flood Control District, Denver, CO. "Treatment BMP Fact Sheets:"

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Brix, H., Schierup, H. (1989): Danish experience with sewage treatment in constructed wetlands. In: Hammer, D.A., ed. (1989): Constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment. Lewis publishers, Chelsea, Michigan, pp. 565–573

- ↑ Davies, T.H.; Hart, B.T. (1990). "Use of Aeration to Promote Nitrification in Reed Beds Treating Wastewater". Constructed Wetlands in Water Pollution Control. pp. 77–84. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-040784-5.50012-7. ISBN 9780080407845.

- ↑ Carpenter, S.R., Caraco, N.F., Correll, D.L., Howarth, R.W., Sharpley, A.N. & Smith, V.H. (1998)Nonpoint pollution of surface waters with phosphorus and nitrogen.Ecological Applications, 8, 559–568.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Wetzel, R.G. (1983): Limnology. Orlando, Florida: Saunders college publishing.

- ↑ Hallin, Sara; Hellman, Maria; Choudhury, Maidul I.; Ecke, Frauke (2015). "Relative importance of plant uptake and plant associated denitrification for removal of nitrogen from mine drainage in sub-arctic wetlands". Water Research 85: 377–383. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2015.08.060. PMID 26360231. Bibcode: 2015WatRe..85..377H.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mitsch, J.W., Gosselink, J.G. (1986): Wetlands. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, p. 536

- ↑ Guntensbergen, G.R., Stearns, F., Kadlec, J.A. (1989): Wetland vegetation. In Hammer, D.A., ed. (1989): Constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment. Lewis publishers, Chelsea, Michigan, pp. 73–88

- ↑ "Wetlands for Treatment of Mine Drainage". Technology.infomine.com. http://technology.infomine.com/enviromine/wetlands/Welcome.htm.

- ↑ Hedin, R.S., Nairn, R.W.; Kleinmann, R.L.P. (1994): Passive treatment of coal mine drainage. Information Circular (Pittsburgh, PA.: U.S. Bureau of Mines) (9389).

- ↑ Vymazal, J.; Kröpfleova, L. (2008). Wastewater treatment in constructed wetlands with horizontal sub-surface flow. Environmental Pollution. 14. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8580-2. ISBN 978-1-4020-8579-6.

- ↑ Stefanakis, Alexandros; Akratos, Christos; Tsihrintzis, Vassilios (5 August 2014). Vertical Flow Constructed Wetlands: Eco-engineering Systems for Wastewater and Sludge Treatment (1st ed.). Elsevier Science. pp. 392. ISBN 978-0-12-404612-2. https://www.elsevier.com/books/vertical-flow-constructed-wetlands/stefanakis/978-0-12-404612-2.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Tilley, E., Ulrich, L., Lüthi, C., Reymond, Ph., Zurbrügg, C. (2014): Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies – (2nd Revised Edition). Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag), Duebendorf, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-906484-57-0.

- ↑ Stefanakis, Alexandros; Akratos, Christos; Tsihrintzis, Vassilios (5 August 2014). Vertical Flow Constructed Wetlands: Eco-engineering Systems for Wastewater and Sludge Treatment (1st ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. pp. 392. ISBN 9780124046122. https://www.elsevier.com/books/vertical-flow-constructed-wetlands/stefanakis/978-0-12-404612-2.

- ↑ Sanchez-Ramos, David; Aragones, David G.; Florín, Máximo (2019). "Effects of flooding regime and meteorological variability on the removal efficiency of treatment wetlands under a Mediterranean climate" (in en). Science of the Total Environment 668: 577–591. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.006. PMID 30856568. Bibcode: 2019ScTEn.668..577S.

- ↑ Tilley, Elizabeth; Ulrich, Lukas; Lüthi, Christoph; Reymond, Philippe; Zurbrügg, Chris (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies (2nd ed.). Duebendorf, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag). ISBN 978-3-906484-57-0. http://www.eawag.ch/en/department/sandec/publications/compendium/.

- ↑ Aragones, David G.; Sanchez-Ramos, David; Calvo, Gabriel F. (2020). "SURFWET: A biokinetic model for surface flow constructed wetlands" (in en). Science of the Total Environment 723: 137650. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137650. PMID 32229378. Bibcode: 2020ScTEn.723m7650A.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Scholz M., Sadowski A. J., Harrington R. and Carroll P. (2007b), Integrated Constructed Wetlands Assessment and Design for Phosphate Removal. Biosystems Engineering, 97 (3), 415–423.

- ↑ Mustafa A., Scholz M., Harrington R. and Carrol P. (2009) Long-term Performance of a Representative Integrated Constructed Wetland Treating Farmyard Runoff. Ecological Engineering, 35 (5), 779–790.

- ↑ Scholz M., Harrington R., Carroll P. and Mustafa A. (2007a), The Integrated Constructed Wetlands (ICW) Concept. Wetlands, 27 (2), 337–354.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Carty A., Scholz M., Heal K., Gouriveau F. and Mustafa A. (2008), The Universal Design, Operation and Maintenance Guidelines for Farm Constructed Wetlands (FCW) in Temperate Climates. Bioresource Technology, 99 (15), 6780–6792.

- ↑ "For Peat's Sake: Behind the Scenes of Wetland Restoration: Critical Roles for Landscape Architects | The Complete Wetlander". https://www.aswm.org/wordpress/for-peats-sake-behind-the-scenes-of-wetland-restoration-critical-roles-for-landscape-architects/.

- ↑ Walsh, P. (2015). "The return of the swamp". Landscape Architecture Magazine. https://landscapearchitecturemagazine.org/2015/08/25/the-return-of-the-swamp/. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

- ↑ Sievers, Michael; Parris, Kirsten M.; Swearer, Stephen E.; Hale, Robin (June 2018). "Stormwater wetlands can function as ecological traps for urban frogs". Ecological Applications 28 (4): 1106–1115. doi:10.1002/eap.1714. PMID 29495099.

- ↑ Technical and Regulatory Guidance Document for Constructed Treatment Wetlands (Report). Washington, D.C.: Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council. December 2003. http://www.itrcweb.org/GuidanceDocuments/WTLND-1.pdf.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Langergraber, Guenter; Weissenbacher, Norbert (2017-05-25). "Survey on number and size distribution of treatment wetlands in Austria" (in en). Water Science and Technology 75 (10): 2309–2315. doi:10.2166/wst.2017.112. ISSN 0273-1223. PMID 28541938.

- ↑ Barker, Jacob. "Turning an old dump into new wetland in Happy Valley-Goose Bay". https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/south-escarpment-work-goose-bay-1.4233395.

External links

- Constructed Wetlands – US Environmental Protection Agency — Handbook, studies and related resources

- Publications on constructed wetlands in the library of the Sustainable Sanitation Alliance

|