Earth:History of climate change policy and politics

The history of climate change policy and politics refers to the continuing history of political actions, policies, trends, controversies and activist efforts as they pertain to the issue of climate change.[clarification needed] Climate change emerged as a political issue in the 1970s, where activist and formal efforts were taken to ensure environmental crises were addressed on a global scale.[1] International policy regarding climate change has focused on cooperation and the establishment of international guidelines to address global warming. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is a largely accepted international agreement that has continuously developed to meet new challenges. Domestic policy on climate change has focused on both establishing internal measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and incorporating international guidelines into domestic law. In the 21st century there has been a shift towards vulnerability based policy for those most impacted by environmental anomalies.[2] Over the history of climate policy, concerns have been raised about the treatment of developing nations. Critical reflection on the history of climate change politics provides "ways to think about one of the most difficult issues we human beings have brought upon ourselves in our short life on the planet".[3]

History of climate change mitigation policies

History of activism

History of climate change denial

Political pressure on scientists in the United States

Actions under the Bush Administration around 2007

A survey of climate scientists which was reported to the US House Oversight and Government Reform Committee in 2007, noted "Nearly half of all respondents perceived or personally experienced pressure to eliminate the words 'climate change', 'global warming' or other similar terms from a variety of communications." These scientists were pressured to tailor their reports on global warming to fit the Bush administration's climate change denial. In some cases, this occurred at the request of former oil-industry lobbyist Phil Cooney, who worked for the American Petroleum Institute before becoming chief of staff at the White House Council on Environmental Quality (he resigned in 2005, before being hired by ExxonMobil).[4] In June 2008, a report by NASA's Office of the Inspector General concluded that NASA staff appointed by the White House had censored and suppressed scientific data on global warming in order to protect the Bush administration from controversy close to the 2004 presidential election.[5]

Officials, such as Philip Cooney repeatedly edited scientific reports from US government scientists,[6] many of whom, such as Thomas Knutson, were ordered to refrain from discussing climate change and related topics.[7][8][9]

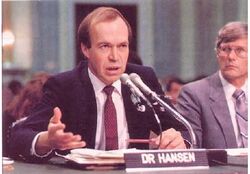

Climate scientist James E. Hansen, director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, wrote in a widely cited New York Times article[10] in 2006, that his superiors at the agency were trying to "censor" information "going out to the public". NASA denied this, saying that it was merely requiring that scientists make a distinction between personal, and official government views, in interviews conducted as part of work done at the agency. When multiple scientists working at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration made similar complaints;[11] government officials again said they were enforcing long-standing policies requiring government scientists to clearly identify personal opinions as such when participating in public interviews and forums.[citation needed]

In 2006, the BBC current affairs program Panorama investigated the issue, and was told, "scientific reports about global warming have been systematically changed and suppressed."[12]

According to an Associated Press release on 30 January 2007:

Climate scientists at seven government agencies say they have been subjected to political pressure aimed at downplaying the threat of global warming.

The groups presented a survey that shows two in five of the 279 climate scientists who responded to a questionnaire complained that some of their scientific papers had been edited in a way that changed their meaning. Nearly half of the 279 said in response to another question that at some point they had been told to delete reference to "global warming" or "climate change" from a report.[13]

The survey was published as a joint report the Union of Concerned Scientists and the Government Accountability Project.[14]

Politically motivated investigations into historic temperature reconstructions

In June 2005, Rep. Joe Barton, chairman of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce and Ed Whitfield, Chairman of the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, sent letters to three scientists Michael E. Mann, Raymond S. Bradley and Malcolm K. Hughes as authors of the studies of the 1998 and 1999 historic temperature reconstructions (widely publicised as the "hockey stick graphs").[15] In the letters he demanded not just data and methods of the research, but also personal information about their finances and careers, information about grants provided to the institutions they had worked for, and the exact computer codes used to generate their results.[16][17] [18]

Sherwood Boehlert, chairman of the House Science Committee, told his fellow Republican Joe Barton it was a "misguided and illegitimate investigation" seemingly intended to "intimidate scientists rather than to learn from them, and to substitute congressional political review for scientific review". The U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS) president Ralph Cicerone wrote to Barton proposing that the NAS should appoint an independent panel to investigate. Barton dismissed this offer.[19][20]

On 15 July, Mann wrote giving his detailed response to Barton and Whitfield. He emphasized that the full data and necessary methods information was already publicly available in full accordance with National Science Foundation (NSF) requirements, so that other scientists had been able to reproduce their work. NSF policy was that computer codes are considered the intellectual property of researchers and are not subject to disclosure, but notwithstanding these property rights, the program used to generate the original MBH98 temperature reconstructions had been made available at the Mann et al. public FTP site.[21]

Many scientists protested Barton's demands.[19][22] Alan I. Leshner wrote to him on behalf of the American Association for the Advancement of Science stating that the letters gave "the impression of a search for some basis on which to discredit these particular scientists and findings, rather than a search for understanding", He stated that Mann, Bradley and Hughes had given out their full data and descriptions of methods.[23][24] A Washington Post editorial on 23 July which described the investigation as harassment quoted Bradley as saying it was "intrusive, far-reaching and intimidating", and Alan I. Leshner of the AAAS describing it as unprecedented in the 22 years he had been a government scientist; he thought it could "have a chilling effect on the willingness of people to work in areas that are politically relevant".[15] Congressman Boehlert said the investigation was as "at best foolhardy" with the tone of the letters showing the committee's inexperience in relation to science.[23]

Barton was given support by global warming sceptic Myron Ebell of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, who said "We've always wanted to get the science on trial ... we would like to figure out a way to get this into a court of law," and "this could work".[23] In his Junk Science column on Fox News, Steven Milloy said Barton's inquiry was reasonable.[25] In September 2005 David Legates alleged in a newspaper op-ed that the issue showed climate scientists not abiding by data access requirements and suggested that legislators might ultimately take action to enforce them.[26]

Boehlert commissioned the U.S. National Academy of Sciences to appoint an independent panel which investigated the issues and produced the North Report which confirmed the validity of the science. At the same time, Barton arranged with statistician Edward Wegman to back up the attacks on the "hockey stick" reconstructions. The Wegman Report repeated allegations about disclosure of data and methods, but Wegman failed to provide the code and data used by his team, despite repeated requests, and his report was subsequently found to contain plagiarized content.[citation needed]

Climatic Research Unit email controversy (2009)

Shift from bipartisanship in the United States

As recent as the 2000s, climate policy was a bipartisan issue. In the Senate, John McCain (R-AZ) introduced the Climate Stewardship Act with Joseph Lieberman (D-CT) in 2003, which aimed to reduce American carbon emissions through policy. In 2005, the Senate also endorsed the view that climate change was happening, and policy needed to be enacted in response to it.[29]

With the risk of losses in profit, the fossil fuel industry enlisted scientists to negate any evidence of climate change.[29] According to a 2015 investigation,[30] Exxon knew about the impacts of fossil fuels on the climate as early as 1977. They carried out their own research and senior scientist James Black concluded that Exxon had a 5 to 10-year period before they need to shift energy strategies. In 1988, Exxon publicly maintained the perspective that climate science was controversial and non-conclusive. In 1998, Exxon contributed to the prevention of the United States’ involvement in the Kyoto Protocol, and ultimately China’s and India’s.[31]

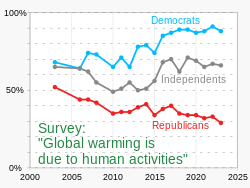

By 2009, polls shows an increase in partisan belief in climate change. Pew Research Center concluded in a 2023 survey that over the past 10 years, democrats and republicans have grown more divided over the subjects of climate change.[32] In 2016, polls showed one-third of Americans were climate skeptics. Climate skepticism is typically associated with right-wing thought,[33] but national panel studies from 2014 and 2016 show that many US republicans do believe in climate change. This data has led psychological scientists to conclude that congressional lawmakers “support policies from their own party and reactively devalue policies from the opposing party."[34]

Development of political concern

In the mid-1970s, climate change shifted from a solely scientific issue to a point of political concern. The formal political discussion of global environment began in June 1972 with the UN Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) in Stockholm.[1] The UNCHE identified the need for states to work cooperatively to solve environmental issues on a global scale.[1]

The first World Climate Conference in 1979 framed climate change as a global political issue, giving way to similar conferences in 1985, 1987, and 1988.[35] In 1985, the Advisory Group on Greenhouse Gases (AGGG) was formed to offer international policy recommendations regarding climate change and global warming.[35] At the Toronto Conference on the Changing Atmosphere in 1988, climate change was suggested to be almost as serious as nuclear war and early targets for CO

2 emission reductions were discussed.[35]

The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) jointly established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988.[36] A succession of political summits in 1989, namely the Francophone Summit in Dakar, the Small Island States meeting, the G7 Meeting, the Commonwealth Summit, and the Non-Aligned Meeting, addressed climate change as a global political issue.[35]

Partisan division

In the late 2000s, the political discourse regarding climate change policy became increasingly polarising.[37] In the United States, the political right has largely opposed climate policy while the political left has favoured progressive action to address environmental anomalies.[38] In a 2016 study, Dunlap, McCright, and Yarosh note the 'escalating polarisation of environmental protection and climate change'[38] discourse in the USA. In 2020, the partisan gap in public opinion regarding the importance of climate change policy was the widest in history.[37] The Pew Research Center found that, in 2020, 78% of Democrats and 21% of Republicans in the USA saw climate policy as a top priority to be addressed by the President and Congress.[39]

In Europe, there is growing tension between right-wing interest in migration and left-wing climate advocacy as primary political concerns.[40] The validity of climate change research and climate scepticism have also become partisan issues in the United States.[38] However in the United Kingdom the right-wing Conservative Party set one of the first net zero goals in the world in 2019.[41]

Development of international policy

Through the creation of multilateral treaties, agreements, and frameworks, international policy on climate change seeks to establish a worldwide response to the impacts of global warming and environmental anomalies. Historically, these efforts culminated in attempts to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions on a country-by-country basis.[1]

In 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) was held in Rio de Janeiro.[35] The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was also introduced during the conference.[35] The UNFCCC established the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities, defined Annex 1 and Annex 2 countries, highlighted the needs of vulnerable nations, and established a precautionary approach to climate policy.[35] In accordance with the convention, the first session of the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP-1) was held in Berlin in 1995.[1]

In 1997, the third session of the Conference of the Parties (COP-3) passed the Kyoto Protocol, which contained the first legally binding greenhouse gas reduction targets.[1] The Kyoto Protocol required Annex 1 countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 5% from 1990 levels between 2008 and 2012.[42]

At the 13th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP-13) in 2007, the Bali Action Plan was implemented to promote a shared vision for the Copenhagen Summit.[35] The Action Plan called for Annex 2 nations to adopt Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs).[43] The Bali Conference also raised awareness for the 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions caused by deforestation.[35]

In 2009, the Copenhagen Accord was created at the 15th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP-15) in Copenhagen, Denmark.[1] Although not legally binding, the Accord established an agreed-upon goal to keep global warming below two degrees Celsius.[1]

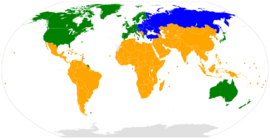

The Paris Agreement was adopted at the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties (COP-21) on the 12th of December 2015.[44] It entered into force on the 4th of November 2016.[45] The agreement addressed greenhouse-gas-emissions mitigation, adaptation, and finance.[45] Its language was negotiated by representatives of 196 state parties at COP-21. As of March 2019, 195 UNFCCC members have signed the agreement and 187 have become party to the agreement.[46]

History of climate change adaptation policies

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Haibach, H. and Schneider, K., 2013. The Politics of Climate Change: Review and Future Challenges. In: O. Ruppel, C. Roschmann and K. Ruppel-Schlichting, ed., Climate Change: International Law and Global Governance: Volume II: Policy, Diplomacy and Governance in a Changing Environment, 1st ed. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, p.372.

- ↑ Ford, James (2007). "Emerging trends in climate change policy: the role of adaptation". Journal of Climate 3: 5–14. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228910050.

- ↑ Dryzek, John S.; Norgaard, Richard B.; Schlosberg, David (2011-08-18). Climate Change and Society: Approaches and Responses. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566600.003.0001. http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566600.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199566600-e-1.

- ↑ US climate scientists pressured on climate change, New Scientist, 31 January 2007

- ↑ Goddard, Jacqui (4 June 2008). "Nasa 'played down' global warming to protect Bush". The Scotsman (Edinburgh). http://news.scotsman.com/world/Nasa-39played-down39-global-.4147975.jp.

- ↑ Campbell, D. (20 June 2003) "White House cuts global warming from report" The Guardian

- ↑ Donaghy, T., et al. (2007) "Atmosphere of Pressure:" a report of the Government Accountability Project (Cambridge, Massachusetts: UCS Publications)

- ↑ Rule, E. (2005) "Possible media attention" Email to NOAA staff, 27 July. Obtained via FOIA request on 31 July 2006. and Teet, J. (2005) "DOC Interview Policy" Email to NOAA staff, 29 September. Originally published by Alexandrovna, L. (2005) "Commerce Department tells National Weather Service media contacts must be pre-approved" The Raw Story, 4 October. Retrieved 22 December 2006.

- ↑ Zabarenko, D. (2007) "'Don't discuss polar bears:' memo to scientists" Reuters

- ↑ Revkin, Andrew C. (29 January 2006). "Climate Expert Says NASA Tried to Silence Him". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/29/science/earth/29climate.html?ei=5088&en=28e236da0977ee7f&ex=1296190800&pagewanted=all.

- ↑ Eilperin, J. (6 April 2006) "Climate Researchers Feeling Heat From White House" The Washington Post

- ↑ "Climate chaos: Bush's climate of fear". BBC Panorama. 1 June 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/panorama/5005994.stm.

- ↑ "Groups Say Scientists Pressured On Warming". CBC and Associated Press. 30 January 2007. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/01/30/politics/main2413400.shtml.

- ↑ Donaghy, Timothy; Freeman, Jennifer; Grifo, Francesca; Kaufman, Karly; Maassarani, Tarek; Shultz, Lexi (February 2007). "Appendix A: UCS Climate Scientist Survey Text and Responses (Federal)". Atmosphere of Pressure – Political Interference in Federal Climate Science. Union of Concerned Scientists & Government Accountability Project. http://www.whistleblower.org/storage/documents/AtmosphereOfPressure.pdf.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 editorial (23 July 2005). "Hunting Witches". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/07/22/AR2005072201658.html.

- ↑ Richard Monastersky (1 July 2005). Congressman Demands Complete Records on Climate Research by 3 Scientists Who Support Theory of Global Warming — Archives. http://chronicle.com/article/Congressman-Demands-Complete/121447/. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ↑ "The Committee on Energy and Commerce, Joe Barton, Chairman". Letters Requesting Information Regarding Global Warming Studies. U.S. House of Representatives. 23 June 2005. http://energycommerce.house.gov/108/Letters/06232005_1570.htm.

- ↑ Joe Barton; Ed Whitfield (23 June 2005). "letter to Michael Mann". United States House Committee on Energy and Commerce. http://energycommerce.house.gov/108/Letters/062305_Mann.pdf.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Juliet Eilperin (18 July 2005). "GOP Chairmen Face Off on Global Warming". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/07/17/AR2005071701056.html.

- ↑ Henry A. Waxman (1 July 2005). "Letter to Chairman Barton". Henry Waxman House of Representatives website. http://www.henrywaxman.house.gov/UploadedFiles/Letter_to_Chairman_Barton.pdf.

- ↑ Michael E. Mann (15 July 2005). "Letter to Chairman Barton and Chairman Whitfield". RealClimate. http://www.realclimate.org/Mann_response_to_Barton.pdf. Gavin Schmidt; Stefan Rahmstorf (18 July 2005). "Scientists respond to Barton". RealClimate. http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2005/07/barton-and-the-hockey-stick/.

- ↑ 20 scientists as listed (15 July 2005). "letter to Chairman Barton and Chairman Whitfield". RealClimate. http://www.realclimate.org/Scientists_to_Barton.pdf.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Roland Pease (18 July 2005). "Science/Nature | Politics plays climate 'hockey'". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/4693855.stm.

- ↑ Alan I. Leshner (13 July 2005). "www.aaas.org". American Association for the Advancement of Science. http://www.aaas.org/news/releases/2005/0714letter.pdf.

- ↑ Steven Milloy (31 July 2005). "Tree Ring Circus". Fox News. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,163999,00.html.

- ↑ "The Weekly Closer from U.S. Senate, September 23, 2005.". https://www.senate.gov/comm/environment_and_public_works/general/repweeklycloser/TheWeeklyCloser9_23_05.pdf.

- ↑ "As Economic Concerns Recede, Environmental Protection Rises on the Public's Policy Agenda / Partisan gap on dealing with climate change gets even wider". Pew Research Center. 13 February 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/02/13/as-economic-concerns-recede-environmental-protection-rises-on-the-publics-policy-agenda/. (Discontinuity resulted from survey changing in 2015 from reciting "global warming" to "climate change".)

- ↑ Saad, Lydia (20 April 2023). "A Steady Six in 10 Say Global Warming's Effects Have Begun". Gallup, Inc.. https://news.gallup.com/poll/474542/steady-six-say-global-warming-effects-begun.aspx.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Fiske, S. 2016. “Climate Skepticism” inside the Beltway and across the Bay. In Anthropology and Climate Change: From Actions to Transformations. S. Crate and M. Nuttall, eds. Pp. 319-325. New York: Routledge.

- ↑ Banjeree, Neela; Cushman Jr., John H; Hasemyer, David; Song, Lisa. Exxon: The Road Not Taken. Inside Climate News. 2015. https://insideclimatenews.org/project/exxon-the-road-not-taken/

- ↑ Hall, Shannon. “Exxon Knew about Climate Change almost 40 years ago.” Scientific American. 26 October 2015. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/exxon-knew-about-climate-change-almost-40-years-ago/

- ↑ Tyson, Alec; Funk, Cary; Kennedy, Brian. “What the data says about Americans’ views of climate change.” Pew Research Center. 9 August 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/08/09/what-the-data-says-about-americans-views-of-climate-change/

- ↑ Yan, Pu; Schroeder, Ralph; Stier, Sebastian. “Is there a link between climate change scepticism and populism? An analysis of web tracking and survey data from Europe and the US.” Information, Communication & Society. Vol: 25, Iss: 10. 7 January 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1864005

- ↑ Van Boven, Leaf; Ehret, Phillip J; Sherman, David K. “Psychological Barriers to Bipartisan Public Support for Climate Policy.” Perspectives on Psychological Science. Vol: 13, Iss: 4. 2 July 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617748966

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 35.6 35.7 35.8 Gupta, Joyeeta (2010). "A history of international climate change policy". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 1 (5): 636–653. doi:10.1002/wcc.67. ISSN 1757-7780. Bibcode: 2010WIRCC...1..636G.

- ↑ "History — IPCC". https://www.ipcc.ch/about/history/.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Popovich, Nadja (2020-02-20). "Climate Change Rises as a Public Priority. But It's More Partisan Than Ever." (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/02/20/climate/climate-change-polls.html.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Dunlap, Riley E.; McCright, Aaron M.; Yarosh, Jerrod H. (2016-09-02). "The Political Divide on Climate Change: Partisan Polarization Widens in the U.S." (in en). Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 58 (5): 4–23. doi:10.1080/00139157.2016.1208995. ISSN 0013-9157. Bibcode: 2016ESPSD..58e...4D.

- ↑ Kennedy, Brian. "U.S. concern about climate change is rising, but mainly among Democrats" (in en-US). https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/16/u-s-concern-about-climate-change-is-rising-but-mainly-among-democrats/.

- ↑ Walker, Shaun (2019-12-02). "Migration v climate: Europe's new political divide" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/dec/02/migration-v-climate-europes-new-political-divide.

- ↑ "UK net zero target" (in en). 2020-04-20. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/article/explainer/uk-net-zero-target.

- ↑ DiMento, Joseph F; Doughman, Pamela (2014). Climate Change: What It Means for Us, Our Children, and Our Grandchildren. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-32230-0. OCLC 875633405.

- ↑ United Nations Development Programme. (2008). The Bali Action plan: key issues in the climate negotiations: Summary for Policy Makers. Retrieved from http://content-ext.undp.org/aplaws_assets/2512309/2512309.pdf

- ↑ Sutter, John D.; Berlinger, Joshua (12 December 2015). "Final draft of climate deal formally accepted in Paris". Cable News Network, Turner Broadcasting System, Inc.. http://www.cnn.com/2015/12/12/world/global-climate-change-conference-vote/.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "The Paris Agreement". 2020. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement.

- ↑ "Paris Agreement". United Nations Treaty Collection. 8 July 2016. https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-7-d&chapter=27&clang=_en.

|