Finance:Environmental impact of cryptocurrencies

Cryptocurrencies that rely on proof of work technology, notably Bitcoin and Ethereum, have been criticized for the amount of electricity consumed by mining.[1][2] This has led to greater interest in cryptocurrencies that use proof of stake.[3][4]

Bitcoin energy consumption

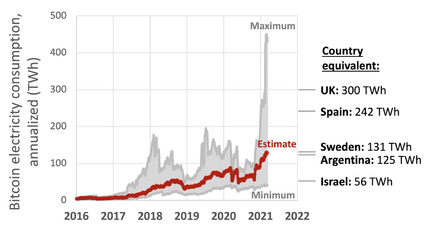

As of 2022[update], the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF) estimates that Bitcoin consumes 131 TWh annually, representing 0.29% of the world's energy production and 0.59% of the world's electricity production, ranking Bitcoin mining between Ukraine and Egypt in terms of electricity consumption.[5][6]

George Kamiya, writing for the International Energy Agency, says that "predictions about Bitcoin consuming the entire world's electricity" are sensational, but that the area "requires careful monitoring and rigorous analysis".[7] One study done by Michael Novogratz's Galaxy Digital, a cryptocurrency investment firm, claimed that Bitcoin mining used less energy than the traditional banking system.[8]

Sources of energy

Until 2021, according to the CCAF much of Bitcoin mining was done in China.[9][10] Chinese miners used to rely on cheap coal power in Xinjiang[11][12] in late autumn, winter and spring, and then migrate to regions with overcapacities in low-cost hydropower, like Sichuan, between May and October. In June 2021 China banned Bitcoin mining[13] and Chinese miners moved to other countries.[14] By December 2021, the global hashrate had mostly recovered to a level before China's crackdown, with increased shares of the total mining power coming from the U.S. (35.4%), Kazakhstan (18.1%), and Russia (11%) instead.[15]

As of September 2021, according to the New York Times , Bitcoin's use of renewables ranged from 40% to 75%.[1] According to the Bitcoin Mining Council and based on a survey of 32% of the global network, 56% of bitcoin mining came from renewable resources in Q2 2021.[16] However, experts and government authorities have suggested that the use of renewable energy by the cryptocurrency mining sector may limit the availability of such clean energy for ordinary uses by the general population.[1][17][18]

Proof of stake and other types of networks

While the largest proof of work (PoW) blockchains such as Bitcoin and Ethereum consume energy on the scale of medium-sized countries, demand from proof of stake (PoS) blockchains is on a scale equivalent to a housing estate. Various sources have cited 2021 figures compiled by TRG Datacentres in Texas of energy use in kilowatt hours per transaction: IOTA (0.00011); XRP (0.0079); Chia (0.023); Dogecoin (0.12); Cardano (0.5479); Litecoin (18.522); Bitcoin Cash (18.957); Ethereum (62.56); and Bitcoin (707). This has led to the identification of "eco-friendly cryptocurrencies”: Chia, IOTA, Cardano, Nano, Solarcoin and Bitgreen.[19][20]

Chia is based on a proof of space algorithm, which uses a lot less power because it relies on storage devices, not computer processing power.[21] However, the huge number of hard discs needed produces considerable amounts of electronic waste.[22][23]

Academics and researchers have used various methods for estimating the energy use and energy efficiency of blockchains. The Germany-based Crypto Carbon Ratings Institute (CCRI) studied the six largest PoS networks in May 2021. Its conclusions in terms of annual consumption (kWh/yr) were: Polkadot (70,237), Tezos (113,249), Avalanche (489,311), Algorand (512,671), Cardano (598,755) and Solana (1,967,930). This equates to Polkadot consuming 7 times the electricity of an average U.S. home, Cardano 57 homes and Solana 200 times as much. The research concluded that PoS networks consumed 0.001% the electricity of the Bitcoin network.[24]

The table below summarises the TRG and CCRI results alongside research from the University College London (UCL).[25] These sources give a measure of energy efficiency in terms of energy use per transaction.

| UCL | CCRI | TRG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorand (PoS) | 0.17–5.34 | 2.70 | |

| Cardano (PoS) | 12.39–378.54 | 51.59 | 547.9 |

| Polkadot (PoS) | 3.78–115.56 | 17.42 | |

| Tezos (PoS) | 0.36–10.96 | 41.45 | |

| Bitcoin (PoW) | 360,393–3,691,407 | 1,722,240 | 707,000 |

| VisaNet (as a comparator) | 3.58 | 1.5 |

Negative impact of mining

Bitcoin carbon emissions

Concerns about Bitcoin's environmental impact relate the network's energy consumption to carbon emissions.[26][27] The difficulty of translating the energy consumption into carbon emissions lies in the decentralized nature of Bitcoin impeding the ability of researchers to identify miners geographically and so examine the electricity mix used. The results of studies into the carbon footprint vary.[28][29][30][31] A 2018 study published in Nature Climate Change claimed that Bitcoin "could alone produce enough CO

2 emissions to push warming above 2C within less than three decades."[30] However, three later studies in Nature Climate Change dismissed this analysis on account of its poor methodology and false assumptions with one study concluding: "[T]he scenarios used by Mora et al are fundamentally flawed and should not be taken seriously by the public, researchers, or policymakers."[32][33][34] According to studies published in Joule and American Chemical Society in 2019, Bitcoin's annual energy consumption results in annual carbon emission ranging from 17[35] to 22.9 MtCO

2 which is comparable to the level of emissions of countries as Jordan and Sri Lanka or Kansas City.[31] However, other academic studies report a much broader range of carbon footprint estimates. For instance, according to a study published in Finance Research Letters in 2021, differences in underlying assumptions and variation in the coverage of time periods and forecast horizons have led to Bitcoin carbon footprint estimates spanning from 1.2-5.2 Mt CO2 to 130.50 Mt CO2 per year.[36]

Electronic waste

Researchers estimate that electronic waste generated by Bitcoin mining devices amounts to 30.7 metric kilotonnes annually as of May 2021. Due to the consistent increase of the Bitcoin network's hashrate, mining devices are estimated to have an average lifespan of 1.29 years until they become unprofitable and need to be replaced. Mining devices based on ASIC technology, the standard hardware for mining, are specialized and cannot be repurposed for another use, and hence become electronic waste once they become unprofitable.[37][38]

Efforts to reduce impact of mining

Some major cryptocurrencies are implementing technical measures to reduce the negative environmental impact.

Bitcoin developers are working on the Lightning Network that would reduce energy demand of the network by moving most transactions off the blockchain.[39][better source needed]

Ethereum is planning a transition from proof of work to a proof of stake algorithm. This could reduce the network's energy demand by 99%.[39][40]

Possible remedies

The development of intermittent renewable energy sources, such as wind power and solar power, is challenging because they cause instability in the electrical grid. Several papers concluded that these renewable power stations could use the surplus energy to mine Bitcoin and thereby reduce curtailment, hedge electricity price risk, stabilize the grid, increase the profitability of renewable energy infrastructure, and therefore accelerate transition to sustainable energy and decrease Bitcoin's carbon footprint.[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48]

Some hydroelectric plants are using the excess power to mine Bitcoin.[49][50] According to the owners of Mechanicville Hydroelectric Plant, the mining saved the plant from dismantlement.[49]

Reversible computing chips and hash recycling could possibly provide some advantage to bitcoin mining in forms of reduced energy usage and e-waste, but the reversible computing is still at its early stages. The paper [51] suggests starting research and development on reversible bitcoin mining chips and also hash recycling for providing entropy to pseudorandom number generation.

Climate-related criticism of Bitcoin is primarily based on the network’s absolute carbon emissions, without considering its market value. However, when taking a relative emission perspective that connects Bitcoin’s carbon emissions to its market value, one study suggests that Bitcoin investments can be less carbon-intensive than standard equity investments. The addition of Bitcoin to a diversified equity portfolio can thus reduce the portfolio’s aggregate carbon footprint.[36]

A 2022 study concluded that cryptocurrencies and other blockchain applications can support the transition to a circular economy and the underlying three principles of reducing, reusing, and recycling. Cryptocurrencies and token rewards can be used to incentivize the sustainable behaviour of individuals[52]. For example, token reward models can incentivize individuals to recycle. There are also several plastic cleanup incentive mechanisms that rely on token rewards.[53]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Huang, Jon; O’Neill, Claire; Tabuchi, Hiroko (2021-09-03). "Bitcoin Uses More Electricity Than Many Countries. How Is That Possible?" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/09/03/climate/bitcoin-carbon-footprint-electricity.html.

- ↑ Olivia Rudgard (2022) “Environmental charities ditch cryptocurrencies after admitting they damage the planet”, The Telegraph, 24 April. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2022/04/24/environmental-charities-ditch-cryptocurrencies-admitting-damage/

- ↑ Wall Street Journal (2021) "Cardano’s Ada Wants to Solve Some of Crypto’s Biggest Challenges", 28 September. https://www.wsj.com/video/series/wsj-explains/cardanos-ada-wants-to-solve-some-of-cryptos-biggest-challenges/A0EDF5B1-F656-4674-A55C-D703622E85EE

- ↑ Katie Martin and Billy Nauman (2021) “Bitcoin’s growing energy problem: It’s a dirty currency”, 20 May, Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/1aecb2db-8f61-427c-a413-3b929291c8ac

- ↑ "Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI)" (in en). https://ccaf.io/cbeci/index/comparisons.

- ↑ "How bad is Bitcoin for the environment really?". 12 February 2021. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/bitcoin-environment-mining-energy-cryptocurrency-b1800938.html. "requires nearly as much energy as the entire country of Argentina"

- ↑ Kamiya, George. "Commentary: Bitcoin energy use - mined the gap". https://www.iea.org/commentaries/bitcoin-energy-use-mined-the-gap.

- ↑ "Bitcoin mining actually uses less energy than traditional banking, new report claims" (in en). 2021-05-18. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/bitcoin-mining-environment-climate-crypto-b1849211.html.

- ↑ "Bitcoin is literally ruining the earth, claim experts". The Independent. 6 December 2017. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/news/bitcoin-environment-green-energy-power-global-warming-climate-change-a8094661.html.

- ↑ "The Hard Math Behind Bitcoin's Global Warming Problem". WIRED. 15 December 2017. https://www.wired.com/story/bitcoin-global-warming/.

- ↑ Ponciano, Jonathan (18 April 2021). "Crypto Flash Crash Wiped Out $300 Billion In Less Than 24 Hours, Spurring Massive Bitcoin Liquidations" (in en). Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jonathanponciano/2021/04/18/crypto-flash-crash-wiped-out-300-billion-in-less-than-24-hours-spurring-massive-bitcoin-liquidations/.

- ↑ Murtaugh, Dan (9 February 2021). "The Possible Xinjiang Coal Link in Tesla's Bitcoin Binge" (in en). Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-09/tesla-s-bitcoin-binge-spells-overtime-for-xinjiang-coal-miners.

- ↑ "Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI)" (in en). https://ccaf.io/cbeci/mining_map.

- ↑ Sigalos, MacKenzie (2021-07-20). "Bitcoin mining isn't nearly as bad for the environment as it used to be, new data shows" (in en). https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/20/bitcoin-mining-environmental-impact-new-study.html.

- ↑ Mellor, Sophie (9 December 2021). "Bitcoin miners have returned to the record activity they had before China's crypto crackdown" (in en). Fortune. https://fortune.com/2021/12/09/bitcoin-miners-hashrate-record-activity-china-crypto-crackdown-kazakhstan/.

- ↑ Ramasubramanian, Sowmya (2021-07-08). "Bitcoin mining uses 56% green energy, mining council says" (in en-IN). The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/technology/bitcoin-mining-uses-56-green-energy-mining-council-says/article35208061.ece.

- ↑ "Crypto-assets are a threat to the climate transition – energy-intensive mining should be banned". 5 November 2021. https://www.fi.se/en/published/presentations/2021/crypto-assets-are-a-threat-to-the-climate-transition--energy-intensive-mining-should-be-banned/.

- ↑ Szalay, Eva (19 January 2022). "EU should ban energy-intensive mode of crypto mining, regulator says". Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/8a29b412-348d-4f73-8af4-1f38e69f28cf.

- ↑ Rachel Lacey (2022) “Everything you need to know about eco-friendly cryptocurrencies”, The Times, 1 March. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/money-mentor/article/eco-friendly-cryptocurrencies/

- ↑ Gedeon, Kimberly (1 June 2021). "The most energy-efficient cryptocurrencies — Tesla's top picks to replace Bitcoin" (in en). https://www.laptopmag.com/uk/best-picks/most-energy-efficient-cryptocurrencies-the-best-picks-for-teslas-new-coin.

- ↑ By (2021-07-07). "What's Chia, And Why Is It Eating All The Hard Drives?" (in en-US). https://hackaday.com/2021/07/07/whats-chia-and-why-is-it-eating-all-the-hard-drives/.

- ↑ Smith, Andrew (2021-05-29). "Chia, the environmentally friendly cryptocurrency, is producing e-waste" (in en-US). https://www.thecoinrepublic.com/2021/05/29/chia-the-environmentally-friendly-cryptocurrency-is-producing-e-waste/.

- ↑ Sparkes, Matthew (26 May 2021). "Bitcoin rival Chia 'destroyed' hard disc supply chains, says its boss". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2278696-bitcoin-rival-chia-destroyed-hard-disc-supply-chains-says-its-boss/.

- ↑ Joanna Ossinger (2022) “Polkadot Has Least Carbon Footprint, Crypto Researcher Says”, Bloomberg, 2 February. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-02-02/polkadot-has-smallest-carbon-footprint-crypto-researcher-says

- ↑ Jonathan Spencer Jones (2021) “Proof-of-stake blockchains – not all are equal”, 13 September, Smart Energy International. https://www.smart-energy.com/industry-sectors/new-technology/proof-of-stake-blockchains-not-all-are-equal/

- ↑ Hern, Alex (17 January 2018). "Bitcoin's energy usage is huge – we can't afford to ignore it". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jan/17/bitcoin-electricity-usage-huge-climate-cryptocurrency.

- ↑ Ethan, Lou (17 January 2019). "Bitcoin as big oil: the next big environmental fight?". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jan/17/bitcoin-big-oil-environment-energy.

- ↑ Foteinis, Spyros (2018). "Bitcoin's alarming carbon footprint". Nature 554 (7691): 169. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-01625-x. Bibcode: 2018Natur.554..169F.

- ↑ Krause, Max J.; Tolaymat, Thabet (2018). "Quantification of energy and carbon costs for mining cryptocurrencies". Nature Sustainability 1 (11): 711–718. doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0152-7.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Mora, Camilo (2018). "Bitcoin emissions alone could push global warming above 2°C". Nature Climate Change 8 (11): 931–933. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0321-8. Bibcode: 2018NatCC...8..931M.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Stoll, Christian; Klaaßen, Lena; Gallersdörfer, Ulrich (2019). "The Carbon Footprint of Bitcoin". Joule 3 (7): 1647–1661. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2019.05.012.

- ↑ Masanet, Eric (2019). "Implausible projections overestimate near-term Bitcoin CO2 emissions". Nature Climate Change 9 (9): 653–654. doi:10.1038/s41558-019-0535-4. Bibcode: 2019NatCC...9..653M.

- ↑ Dittmar, Lars; Praktiknjo, Aaron (2019). "Could Bitcoin emissions push global warming above 2°C?". Nature Climate Change 9 (9): 656–657. doi:10.1038/s41558-019-0534-5. Bibcode: 2019NatCC...9..656D.

- ↑ Houy, Nicolas (2019). "Rational mining limits Bitcoin emissions". Nature Climate Change 9 (9): 655. doi:10.1038/s41558-019-0533-6. Bibcode: 2019NatCC...9..655H.

- ↑ Köhler, Susanne; Pizzol, Massimo (20 November 2019). "Life Cycle Assessment of Bitcoin Mining". Environmental Science & Technology 53 (23): 13598–13606. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b05687. PMID 31746188. Bibcode: 2019EnST...5313598K.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Baur, Dirk G.; Oll, Josua (2021-11-20). "Bitcoin investments and climate change: A financial and carbon intensity perspective" (in en). Finance Research Letters: 102575. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2021.102575. ISSN 1544-6123. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1544612321005262.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 de Vries, Alex; Stoll, Christian (December 2021). "Bitcoin's growing e-waste problem". Resources, Conservation and Recycling 175: 105901. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105901.

- ↑ "Bitcoin mining producing tonnes of waste". BBC News. 20 September 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-58572385.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Cryptocurrency mining and renewable energy: Friend or foe?". 25 May 2021. https://www.smart-energy.com/renewable-energy/cryptocurrency-mining-and-renewable-energy-friend-or-foe/.

- ↑ "Why Ethereum is switching to proof of stake and how it will work" (in en). https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/03/04/1046636/ethereum-blockchain-proof-of-stake/.

- ↑ Fridgen, Gilbert; Körner, Marc-Fabian; Walters, Steffen; Weibelzahl, Martin (2021-03-09). "Not All Doom and Gloom: How Energy-Intensive and Temporally Flexible Data Center Applications May Actually Promote Renewable Energy Sources" (in en). Business & Information Systems Engineering 63 (3): 243–256. doi:10.1007/s12599-021-00686-z. ISSN 2363-7005. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12599-021-00686-z. "To gain applicable knowledge, this paper evaluates the developed model by means of two use-cases with real-world data, namely AWS computing instances for training Machine Learning algorithms and Bitcoin mining as relevant DC applications. The results illustrate that for both cases the NPV of the IES compared to a stand-alone RES-plant increases, which may lead to a promotion of RES-plants.".

- ↑ Rhodes, Joshua. "Is Bitcoin Inherently Bad For The Environment?" (in en). https://www.forbes.com/sites/joshuarhodes/2021/10/08/is-bitcoin-inherently-bad-for-the-environment/. "Mining and transacting cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoin, do present energy and emissions challenges, but new research shows that there are possible pathways to mitigate some of these issues if cryptocurrency miners are willing to operate in a way to compliment the deployment of more low-carbon energy."

- ↑ "Green Bitcoin Does Not Have to Be an Oxymoron" (in en). https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/green-bitcoin-does-not-have-to-be-an-oxymoron. "One way to invest in Bitcoin that has a positive effect on renewable energy is to encourage mining operations near wind or solar sites. This provides a customer for power that might otherwise need to be transmitted or stored, saving money as well as carbon."

- ↑ Moffit, Tim (2021-06-01). "Beyond Boom and Bust: An emerging clean energy economy in Wyoming" (in en). UC San Diego: Climate Science and Policy. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0zp872rt. "Currently, projects are under development, but the issue of overgenerated wind continues to exist. By harnessing the overgenerated wind for Bitcoin mining, Wyoming has the opportunity to redistribute the global hashrate, incentivize Bitcoin miners to move their operations to Wyoming, and stimulate job growth as a result.".

- ↑ Rennie, Ellie (2021-11-07). "Climate change and the legitimacy of Bitcoin" (in en). Rochester, NY. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3961105. "In responding to these pressures and events, some miners are providing services and innovations that may help the viability of clean energy infrastructures for energy providers and beyond, including the data and computing industry. The paper finds that if Bitcoin loses legitimacy as a store of value, then it may result in lost opportunities to accelerate sustainable energy infrastructures and markets."

- ↑ Eid, Bilal; Islam, Md Rabiul; Shah, Rakibuzzaman; Nahid, Abdullah-Al; Kouzani, Abbas Z.; Mahmud, M. A. Parvez (2021-11-01). "Enhanced Profitability of Photovoltaic Plants By Utilizing Cryptocurrency-Based Mining Load". IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 31 (8): 1–5. doi:10.1109/TASC.2021.3096503. ISSN 1558-2515. Bibcode: 2021ITAS...3196503E. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9483629. "The grid connected photovoltaic (PV) power plants (PVPPs) are booming nowadays. The main problem facing the PV power plants deployment is the intermittency which leads to instability of the grid. [...] This paper investigating the usage of a customized load - cryptocurrency mining rig - to create an added value for the owner of the plant and increase the ROI of the project. [...] The developed strategy is able to keep the profitability as high as possible during the fluctuation of the mining network.".

- ↑ Bastian-Pinto, Carlos L.; Araujo, Felipe V. de S.; Brandão, Luiz E.; Gomes, Leonardo L. (2021-03-01). "Hedging renewable energy investments with Bitcoin mining" (in en). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 138: 110520. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110520. ISSN 1364-0321. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032120308054. "Windfarms can hedge electricity price risk by investing in Bitcoin mining. [...] These findings, which can also be applied to other renewable energy sources, may be of interest to both the energy generator as well as the system regulator as it creates an incentive for early investment in sustainable and renewable energy sources.".

- ↑ Shan, Rui; Sun, Yaojin (2019-08-07). "Bitcoin Mining to Reduce the Renewable Curtailment: A Case Study of Caiso" (in en). USAEE Working Paper. 19-415 (Rochester, NY). https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3436872. "The enormous energy demand from Bitcoin mining is a considerable burden to achieve the climate agenda and the energy cost is the major operation cost. On the other side, with high penetration of renewable resources, the grid makes curtailment for reliability reasons, which reduces both economic and environmental benefits from renewable energy. Deploying the Bitcoin mining machines at renewable power plants can mitigate both problems.".

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Moore, Kathleen (8 July 2021). "Mechanicville hydro plant gets new life". https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/Mechanicville-hydro-plant-gets-new-life-16299115.php.

- ↑ Murillo, Alvaro (12 January 2022). "Costa Rica hydro plant gets new lease on life from crypto mining". https://www.reuters.com/technology/costa-rica-hydro-plant-gets-new-lease-life-crypto-mining-2022-01-11/.

- ↑ Heinonen, Henri T.; Semenov, Alexander (2022). Lee, Kisung; Zhang, Liang-Jie. eds. "Recycling Hashes from Reversible Bitcoin Mining to Seed Pseudorandom Number Generators" (in en). Blockchain – ICBC 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Cham: Springer International Publishing) 12991: 103–117. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-96527-3_7. ISBN 978-3-030-96527-3. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-96527-3_7.

- ↑ Juszczyk, Oskar; Shahzad, Khuram (June 2022). "Blockchain Technology for Renewable Energy: Principles, Applications and Prospects" (in en). Energies 15 (13): 4603. doi:10.3390/en15134603. ISSN 1996-1073. https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/15/13/4603.

- ↑ Böhmecke-Schwafert, Moritz; Wehinger, Marie; Teigland, Robin (2022). "Blockchain for the circular economy: Theorizing blockchain's role in the transition to a circular economy through an empirical investigation" (in en). Business Strategy and the Environment: 1–16. doi:10.1002/bse.3032. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bse.3032.