History:Connections (British documentary)

| Connections | |

|---|---|

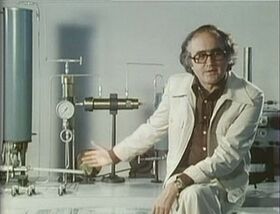

James Burke, the creator and host of Connections, explains the Haber-Bosch Process | |

| Genre | Science education |

| Written by | James Burke |

| Directed by | Mick Jackson |

| Presented by | James Burke |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Original language(s) | English |

| No. of seasons | 3 |

| No. of episodes | 40 |

| Production | |

| Running time | 50 minutes (22 min, Series 2) |

| Release | |

| Original network | BBC |

| Original release | 17 October – 19 December 1978 |

Connections is a science education television series created, written, and presented by science historian James Burke. The series was produced and directed by Mick Jackson of the BBC Science and Features Department and first aired in 1978 (UK) and 1979 (US). It took an interdisciplinary approach to the history of science and invention, and demonstrated how various discoveries, scientific achievements, and historical world events were built from one another successively in an interconnected way to bring about particular aspects of modern technology. The series was noted for Burke's crisp and enthusiastic presentation (and dry humour), historical re-enactments, and intricate working models.

The popular success of the series led to the production of The Day the Universe Changed (1985), a similar program but showing a more linear history of several important scientific developments. Years later, the success in syndication led to two sequels, Connections2 (1994) and Connections3 (1997), both for TLC. In 2004, KCSM-TV produced a program called Re-Connections, consisting of an interview of Burke and highlights of the original series, for the 25th anniversary of the first broadcast in the US on PBS.[1]

Content

Connections explores an "Alternative View of Change" (the subtitle of the series) that rejects the conventional linear and teleological view of historical progress. Burke contends that one cannot consider the development of any particular piece of the modern world in isolation. Rather, the entire gestalt of the modern world is the result of a web of interconnected events, each one consisting of a person or group acting for reasons of their own motivations (e.g., profit, curiosity, religion) with no concept of the final, modern result to which the actions of either them or their contemporaries would lead. The interplay of the results of these isolated events is what drives history and innovation, and is also the main focus of the series and its sequels.

To demonstrate this view, Burke begins each episode with a particular event or innovation in the past (usually ancient or medieval times) and traces the path from that event through a series of seemingly unrelated connections to a fundamental and essential aspect of the modern world. For example, the episode "The Long Chain" traces the invention of plastics from the development of the fluyt, a type of Dutch cargo ship.

Burke also explores three corollaries to his initial thesis. The first is that, if history is driven by individuals who act only on what they know at the time, and not because of any idea as to where their actions will eventually lead, then predicting the future course of technological progress is merely conjecture. Therefore, if we are astonished by the connections Burke is able to weave among past events, then we will be equally surprised to what the events of today eventually will lead, especially events of which we were not even aware at the time.

The second and third corollaries are explored most in the introductory and concluding episodes, and they represent the downside of an interconnected history. If history progresses because of the synergistic interaction of past events and innovations, then as history does progress, the number of these events and innovations increases. This increase in possible connections causes the process of innovation to not only continue, but also to accelerate. Burke poses the question of what happens when this rate of innovation, or more importantly "change" itself, becomes too much for the average person to handle, and what this means for individual power, liberty, and privacy.

Lastly, if the entire modern world is built from these interconnected innovations, all increasingly maintained and improved by specialists who required years of training to gain their expertise, what chance does the average citizen without this extensive training have in making an informed decision on practical technological issues, such as the building of nuclear power plants or the funding of controversial projects such as stem cell research? Furthermore, if the modern world is increasingly interconnected, what happens when one of those nodes collapses? Does the entire system follow suit?

Episodes

Series 1 (1978)

The original 1978 Connections 10-episode documentary television series was created, written, and presented by science historian James Burke and had a companion book (Connections, based on the series). The 1978 Connections companion book was published about the time the middle of the series was airing, so likely was written in parallel to the series and had a post-production editing release.[2] The very popular book was re-released as a work in a 1995 edition, in 1998 (relations to sections below is unknown), and again in 2007 as both hardcover or softcover editions. Since the television series varied in content with each corresponding production run and release, it is likely the companion volumes (as is suggested by the plethora of ISBN codes) are also different works. This 1978 work's coverage deviates in some topics and details being both more in depth and a bit broader, from the lighter coverage of the episodes.

- "The Trigger Effect" details the world's present dependence on complex technological networks through a detailed narrative of New York City and the power blackout of 1965. Agricultural technology is traced to its origins in ancient Egypt and the invention of the plough. The segment ends in Kuwait where, because of oil, society leapt from traditional patterns to advanced technology in a period of only about 30 years.

- "Death in the Morning" examines how being able to test the purity of gold with a touchstone allowed the ancient world to replace a trading system based on barter with one based on cash. This innovation stimulated trade from Greece to Persia, ultimately causing the construction of the huge commercial centre and the Great Library of Alexandria which included Ptolemy's star tables. This wealth of astronomical knowledge aided navigators during the Age of Discovery fourteen centuries later, following the introduction into Europe of lateen sails and sternpost rudders. Mariners who ventured further afield discovered that the magnetised needle of a compass did not actually point to the North Star, leading to investigations into the nature of magnetism by William Gilbert, and thus to the discovery of electricity by way of the sulphur ball of Otto von Guericke. Further interest in atmospheric electricity at the Ben Nevis weather station led to Wilson's cloud chamber which in turn allowed development of both Watson-Watt's radar and (by way of Rutherford's insights) nuclear weaponry.

- "Distant Voices" opens with two strands on developments in horse technology. The first on warfare, from the use of stirrups, improving saddles and moving to larger, stronger horses for carrying knights. The high costs of these led to a hereditary chivalry. The second strand, arising from the end of the 9th century with the development of the wheeled plough, the invention of the horse collar and the horseshoe, and the three-field system. The increased ability to use horses for both work and transport opening up the possibility of creating an agricultural surplus, and moving it for sale. Deep mine shafts flooded and scientists in search of a solution examined vacuums, air pressure, and other natural phenomena.

- "Faith in Numbers" examines the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance from the perspective of how commercialism, climate change, and the Black Death influenced cultural development. He examines the impact of Cistercian waterpower on the Industrial Revolution, derived from Roman watermill technology such as that of the Barbegal aqueduct and mill. Also covered are the Gutenberg printing press, the Jacquard loom, and the Hollerith punch card tabulator that led to modern computer programming.

- "The Wheel of Fortune" traces astrological knowledge in ancient Greek manuscripts from Baghdad's founder, Caliph Al-Mansur, via the Muslim monastery/medical school at Gundeshapur, to the medieval Church's need for alarm clocks (the water horologium and the verge and foliot clock). The clock mainspring gave way to the pendulum clock, but the latter could not be used by mariners, thus the need for precision machining by way of Huntsman's improved steel (1797) and Maudslay's use (1800) of Ramsden's idea of using a screw to better measure (which he took from the turner's trade). This process made a better mainspring and was also used by the Royal Navy to make better blocks. Le Blanc mentioned this same basic idea to Thomas Jefferson, who transmitted this "American system of manufactures" – precision machine-tooling of musket parts for interchangeability – to New Englanders Eli Whitney, John Hall, and Simeon North. The American efficiency expert Frank Gilbreth and his psychologist wife later improved the whole new system of the modern production line.

- "Thunder in the Skies" implicates the Little Ice Age (circa 1300-1850 AD) in the invention of the chimney, as well as knitting, buttons, wainscoting, wall tapestries, wall plastering, glass windows (Hardwick Hall [1597] has "more glass than wall"), and the practice of privacy for sleeping and sex. The genealogy of the steam engine is then examined: Thomas Newcomen's engine for pumping water out of mines (1712); Abraham Darby's cheap iron from coke, James Watt's addition of a second condensing cylinder (for cooling) to the engine (1763); John Wilkinson's improving of cannon boring (for the French military) and cylinder making (for Watt; 1773–75). Wilkinson's brother-in-law, Joseph Priestley, investigated gases, leading Alessandro Volta to invent "bad air" (marsh gas) detectors and ignitors. Meanwhile, Edwin Drake discovered oil (in Pennsylvania), allowing Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach (in Bad Cannstatt) to replace town gas with gasoline as fuel for auto engines (1883). They also invented (in 1892) the carburetor (inspired by the medical atomizers, which also developed from Priestley's work) and a new ignition system inspired by Volta's "bad air" detection spark gun. Finally, piano-maker Wilhelm Kress unsuccessfully attempted (1901) to fly the first seaplane on an Austrian lake using the new gasoline engine.

- "The Long Chain" traces the invention of the fluyt freighter in Holland in the 16th century. Voyages were insured by Edward Lloyd (Lloyd's of London) if the ships' hulls were covered in pitch and tar (which came from the colonies until the American War of Independence in 1776). In Culross, Scotland, Archibald Cochrane (9th Earl of Dundonald) tried to distill coal vapour to get coal tar for ships' hulls, which led to the discovery of ammonia. The search for artificial quinine to treat malaria led to the development of artificial dyes, which Germany used to produce fertilizers to grow wheat and led to the advancement of chemistry which in turn led to DuPont's discovery of polymers such as nylon.

- "Eat, Drink and Be Merry..." begins with plastic, the plastic credit card, and the concept of credit, then leaps back to the time of the dukes of Burgundy, the first state to use credit. The dukes used credit for many luxuries, and to buy more armour for a stronger army. The Swiss opposed the army of Burgundy and invented a new military formation (with soldiers using pikes) called the pike square. The pike square, along with events following the French Revolution, set in motion the growth in the size of armies and in the use of ill-trained peasant soldiers. Feeding these large armies became a problem for Napoleon, which caused the innovation of bottled food. The bottled food was first put in champagne bottles then in tin cans. Canned food was used for armies and for navies. In one of the bottles, the canned food went bad, and people blamed the spoiled food on "bad air", also known as swamp air. Investigations around "bad air" and malaria led to the innovation of air conditioning and refrigeration. In 1892, Sir James Dewar invented a container that could keep liquids hot or cold (the thermos) which led three men – Tsiolkovsky, Robert Goddard, and Hermann Oberth – to construct a large thermal flask for either liquid hydrogen and oxygen or for solid fuel combustion for use in rocket propulsion, applying the thermal flask principle to keep rocket fuel cold and successfully using it for the V-2 rocket and the Saturn V rocket that put man on the Moon.

- "Countdown" connects the invention of the movie projector to improvements in castle fortifications caused by the invention and use of the cannon. The use of the cannon caused changes in castle fortifications to eliminate a blind spot where cannon fire could not reach. This improvement in castle defence caused innovation in offensive cannon fire, which eventually required maps. Thus, a need arose to view and map locations (like a mountain top) from a long distance, which led to the invention of limelight light source, and later the incandescent light. Burke turns to the next ingredient for a movie projector, film. Film is made with celluloid (made with guncotton) which was first invented as a substitute for ivory in billiard balls. Next was the invention of the zoopraxiscope which was first used for a bet to see if a horse's hooves all left the ground at any point while galloping. The zoopraxiscope used frame-by-frame pictures and holes on the side to allow the machine to pull the film forward. Communication signals for railways using Morse's telegraph led to Edison discovering how to speak into a microphone creating bumps on a disc that could be played back—the record player. This final ingredient gave movies sound. In summary, Burke connects the invention of the movie projector to four major innovations in history: the incandescent light, the discovery of celluloid, the projector that uses frame-by-frame pictures on celluloid, and finally, recorded sound.

- "Yesterday, Tomorrow and You" recaps the theme that change causes more change. Burke ties together the modern inventions in which previous episodes had culminated: telecommunications, the computer, the jet engine, plastics, rockets, television, the production line, and the atomic bomb. All of these inventions come together in the B-52 nuclear bomber. Start with the plow, you get irrigation, pottery, craftsmen, civilisation and writing, mathematics, a calendar to predict floods, empires, and a modern world where change happens so rapidly you cannot keep up. What do you do? Stop the change? Throw away all technology and live like cavemen? Decide what change will be allowed by law? Or just accept that the world is changing faster than we can keep up with?

Series 2 (1994)

Released as Connections2:

- "Revolutions" – What do all these things have in common—three grandfathers' lifetimes, two revolutions, 1750 Cornish steam engines for Cornwall's tin mines, water in mines, pumps, steam engines, Watt's copier, carbon paper, matches, phosphorus fertiliser, trains and gene-pool mixing, travelling salesmen, 24-hour production, educated women, the telephone, high-rise buildings, Damascus's swords, steel, diamond, carborundum, graphite, oscilloscope, television, Apollo space program, X-ray crystallography, DNA and gene therapy? You will learn these things in the first episode of Connections2, "Revolutions".

- "Sentimental Journeys" – What do these have in common – Freud, lifestyle crisis, electric shock therapy, hypnotherapy, magnetism, phrenology, penology, physiology, synthetic dyes, the Bunsen burner, absorption, Fraunhofer lines, astronomical telescopes, chromatic aberrations, and surveying? Follow James Burke on the trail of discovering the connections between these and others in "Sentimental Journeys".

- "Getting it Together" – James Burke explains the relationship between hot air balloons and laughing gas, and goes on to surgery, hydraulic-water gardens, hydraulic rams, tunnelling through the Alps, the Orient Express, nitroglycerin, heart attacks and headaches, aspirin, carbolic acid, disinfectants, Maybach-Gottlieb Daimler-Mercedes, carburetors, helicopters, typewriters, punch cards, and IBM.

- "Whodunit?" – This episode starts with a billiard ball and ends with a billiard ball. Along the way, Burke examines Georgius Agricola's De Re Metallica, how mining supported war, the role of money, the Spanish Armada, large ships, problems posed by a wood shortage, glass making, coal, plate glass, mirrors, the sextant, the discovery of granite, and seashells in the mountains, which enabled a new view of the age of the Earth, and Darwin's theory of evolution, Francis Galton's Eugenics, and the forensic use of fingerprints.

- "Something for Nothing" – How do Space Shuttle landings start with the vacuum which was forbidden by the Church? Burke takes us on an adventure with barometers, weather forecasting, muddy and blacktop roads, rain runoff, sewage, a cholera epidemic, hygiene, plumbing, ceramics, vacuum pumps, compressed-air drills, tunnels in the Alps, train air brakes, hydroelectric power, the electric motor, Galvani's muscle-electricity connection, Volta's battery, and gyroscopes.

- "Echoes of the Past" – The past in this case starts with the tea in Dutch-ruled India, examines the Japanese tea ceremony, Zen Buddhism, porcelain, the architecture of Florence, Delftware, Wedgwood, Free Masons, secret codes, radio-telephones, cosmic background radiation and—finally – radio astronomy, which listens to "Echoes of the Past".

- "Photo Finish" – Another series of discoveries examined by Burke includes Eastman Kodak's Brownie, the disappearing elephant scare of 1867, billiard balls, celluloid as a substitute for ivory, false teeth that explode, gun cotton, double shot sound of a bullet, Mach's shock wave, aerodynamics, nuclear bombs, Albert Einstein's relativity, Einstein's selenium, movie talkies, the vacuum tube amplifier, radio, railroad's use of wood, coal tar, gas lights, creosote, rubber, the Zeppelin, the automobile, and finally how Adeline vulcanises tires.

- "Separate Ways" – Burke shows how to get from sugar to atomic weapons by two totally independent paths. The first involves African slaves, Abolitionist societies, Sampson Lloyd II, wire, suspension bridges, galvanised wire, settlement of the Wild West, barbed wire, canned corn, and cadmium. The second path involves sweet tea, rum, a double boiler, the steam engine, Matthew Boulton, English currency, the pantograph, electroplating, and cathode ray tubes.

- "High Times" – The connection between polyethylene and Big Ben is a few degrees of separation, so let us recount them: polyethylene, radar, soap, artificial dyes, color perception, tapestries, Far East goods, fake lacquer furniture, search for shorter route to Japan, Hudson in Greenland, the discovery of plentiful whales, printing the Bible, Mercator map, Martin Luther's protest, star tables, Earth as a flattened sphere, and George Graham's clock which of course leads to Big Ben.

- "Deja Vu" – James Burke provides evidence that history does repeat itself by examining the likes of black and white movies, conquistadors, Peruvian Incas, small pox, settlements that look like Spain's cities, the gold abundance ending up in Belgium, Antwerp, colony exploitation, the practice of burying treasure to avoid pirates, Port Royal's pirates, earthquakes, the College of William and Mary, military discipline, Alexander Humboldt's observation on the environment, Friedrich Ratzel's superstate Lebensraum, and Haushofer's world domination.

- "New Harmony" – A dream of utopia is followed from microchips to Singapore, from the transistor to its most important element, germanium, to Ming vases and cobalt fakes (which contribute to the blue in blue tiles used in special Islamic places), and mosaics in Byzantium, the donation of Constantine, Portuguese navigation by stars, the "discovery" of Brazil, Holland's tolerance, diamond merchants, optics, microscopes, beasts of science, Frankenstein's monster, and finally New Harmony.

- "Hot Pickle" – Burke starts out in a spice market in Istanbul where you can find hot pickle, recounts the taking of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453, follows the trail of pepper, tea, and opium and the exploitation of addicts, moves to the jungles of Java, then to zoos, the use of canaries as carbon monoxide detectors, how George Stephenson used his consolation prize to build a locomotive, which led to the battle between the Monitor and the Merrimack. Next we visit a sea island off the coast of South Carolina, where children of slaves are schooled. By the way, they picked cotton, which leads us to gaslight and air conditioning. Georgia Cayvan's glass dress leads to the neodymium glass laser, (which was used in the Gulf War). And the armed switch for firing a missile is also called a "hot pickle".

- "The Big Spin" is what California's lottery TV show is called. And lottery being a game of chance, from here Burke takes us through Alexander Fleming's chance discovery of penicillin, to Rudolf Virchow's observation that contaminated water is related to health, to Schliemann's search for the City of Troy, the theft of a discovered treasure, and to Virchow's criminology. From there we proceed to anthropology, the classification of life forms, Francis Bacon, the statistics of mortality, life expectancy, statistical math, Priestley's carbonated water, the soda fountain, petroleum oil, some French fossil hunters, seismology, and impossible-to-predict earthquakes.

- "Bright Ideas" – gin and tonic was invented to combat malaria in British colonies like Java, which leads us to Geneva, where cleanliness is an obsession. Here, tonic water was sealed with a disposable bottle cap, and razors became disposable, leading us to Huntsman's steel, invaluable for making clock springs. We take a little trip through lighthouses, the education of orphans, psycho-physics, the law of the just noticeable difference, which is the idea behind stellar magnitudes, which leads us to discovering the size of the universe.

- "Making Waves" – a permanent wave in ladies' hair is aided by curlers, and this leads us to explore borax, taking us to Switzerland, Johann Sutter's scam, and Sutter's Mill, and that means the discovery of gold leading to the 1848 California gold rush. Americans then cut into the English tea market with the aide of the Yankee Clipper, which played a big role in the gold rush. A fungus from America created the Great Famine of Ireland, resulting in the importing of corn, but laws prevented the Yankee clippers from being used until it was too late to save Ireland. Finally, the laws were changed, leading to franking fraud, which was overcome by special printing of postage stamps, which gave us wallpaper, and a thickening agent, leading us to the Canal du Midi, the American war for independence, resettlement in Scotland, highlanders in Nova Scotia and—finally—the Queen Elizabeth 2.

- "Routes" – Jethro Tull, a sick English lawyer, recuperates sipping wine and contributes the hoe to help fix farming problems. Farm production is not going so well in France, either. François Quesnay (doctor of King Louis XV's mistress) suggests a solution based on his complete misunderstanding of English farming techniques. Laissez-faire was his erroneous idea. It also got the people to demand social laissez-faire. His inciting the public's rebellion against the monarchy led to France's invasion of Geneva. The French Revolution led to personal exploration of the senses. Berlin doctor Müller reasoned that each sense does a different job and the nervous system analyses what the senses are telling one. Helmholtz's pupil, Hertz, discovered that sound and electricity have a wave-like nature in common. Guglielmo Marconi takes this a step further by sending and receiving signals very long distances across the earth. The BBC realised that the radio waves were reflected by the ionosphere, and Hess was the first to suggest that the ionization was due to "Hess rays" later related to solar activity. But World War II started and adding machines were needed to aim artillery, so digital computing was invented. Thus was enabled the GPS which tells travelers their "Routes".

- "One Word" – The one word that changed everything was "filioque", but we must make a trip to Constantinople, visit the Renaissance, meet Aldus Manutius of Venice, explore abbreviations, learn about Italic print, which resulted in an overload of books, requiring the development of a cataloguing system, which was complicated for those seeking education, where Komensky was innovating with pictorial textbooks. And that brings us to church intolerance, James Watt and the Industrial Revolution, cerium, the asteroid Ceres, Gauss's mathematics, and cultural anthropology.

- "Sign Here" – Murphy's Law says you need insurance from Lloyd's of London, so pack your bags to study international law and protect yourself from piracy by calculating the probability. You better study Pascal's math for that, but you might find yourself jailed for free thinking. While you are in jail, study some sign language, or at least learn to speak better than Eliza Doolittle. Henry Higgins's waveform recordings lead you to the telephone, the invention of shorthand, the radiometer, gas flow, the Wright brothers' aeroplane, lubrication, ball bearings and a ballpoint pen so you can "Sign Here".

- "Better Than the Real Thing" starts in the 1890s with bicycles and bloomers and then takes a look at boots, zippers, sewing machines, and infinitesimal difference. Speaking of small, we look at microscopic germs, polarized light, sugar, coal, iron, microbubbles, the spectroscope, night vision, beriberi resulting from polished rice, chickens, war rationing, and finally, we arrive at vitamins in a pill.

- "Flexible Response" is a whimsical look at the myth of the English longbow, Robin Hood, sheep, the need to drain land with windmills, the effect of compound interest, decimal fractions (wrongly pointing to the US, not Russia, as the first country with decimal currency; in fact the US did not exist at the time of Russian decimalisation in 1704), increased productivity, the Erie Canal, railroads, telegraphs, department stores, Quaker Oats, X-ray diagnostics, biofeedback, and servo control systems in a Panavia Tornado aircraft.

Series 3 (1997)

Released as Connections3

- "Feedback" – Electronic agents on the internet and wartime guns use feedback techniques discovered in the first place by Claude Bernard, whose vivisection experiments kick off animal rights movements called humane societies that really start out as lifeboat crews rescuing people from all the shipwrecks happening because of all the extra ships out there that are using Matthew Maury's data on wind and currents transmitted by the radio telegraph, invented by Samuel Morse, who is also a painter whose hero is Washington Allston, who spends time in Italy with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who comes to Malta and spies for the governor Alexander Ball, who saved Admiral Horatio Nelson's skin so he can go head over heels for Emma Hamilton in Naples, resulting in an illegitimate son. Emma became notable in the Electrico-Magnetico Celestial Bed, where you go regain your fertility through electricity, and you can get more whisky thanks to Joseph Black, who determined the latent heat of vaporisation in steam. James Watt borrowed that information to make a better steam engine. Watt is linked to Roebuck who discovered chlorine bleach which eventually is used to make white paper. The paper is used for decorating walls by William Morris, who is a socialist with Annie Besant, who is a vegetarian just like the Seventh-day Adventists. And we end up with W.K. Kellogg's cornflakes.

- "What's in a Name?" – Remember the cornflakes from last episode? Because corncobs make adhesives to bond carborundum discovered by Edward Goodrich Acheson, otherwise known as silicon carbide, to grinding wheels used to grind lightbulbs, silicon carbide is also then used as protection against armour-piercing shells developed to hit tanks that start life as American tractors, which use diesel engines developed from funding from Krupp, who inspired Bismarck's welfare scheme based on Quetelet's statistics that inspired the Charles Babbage's difference engine, whose punch cards were used to rivet the SS Great Eastern, the monster ship that laid the transatlantic cable insulated with gutta-percha used to manufacture golf balls for factory managers in industrial Scotland, where James Watt had a run-in with Cavendish, whose protegee was James Macie, also called James Smithson, who caused all the row in the capitol building, so the money got used to set up a world-renowned institution named after James Macie's new family name, which was Smithson: The institution known as the Smithsonian.

- "Drop the Apple" – At the Smithsonian, we learn of electric crystals that help Pierre and Marie Curie discover what they call radium, and then Langevin uses the piezoelectric crystal to develop sonar that helps save Liberty ships (from German U-boats) put together with welding techniques using acetylene made with carbon arcs, also working the arc lights with clockwork regulators built by Foucault, whose pendulum helps him to take pictures of solar eclipses. Also thanks to ash from seaweed, interchangeable parts for clocks, the world of opera, and gurus, we get Einstein's theory of the gravity effect, which means Newton's universe is gone and you can drop the apple.

- "An Invisible Object" – Black holes in space, seen by the Hubble Space Telescope, brought into space with hydrazine fuel, which was a byproduct of fungicides for French vines, fuelled by quarantine conventions and money orders, American Express and Buffalo Bill, Vaudeville and French battles, Joan of Arc and the Inquisition, Jews welcomed by Turks, who lost to Maltese knights with surgeons trained on pictures by Titian, in Augsburg, where goldsmiths made French money to pay for tobacco. That triggered logarithms and slide rules made by clock makers, who also made pressure cookers that sterilised French beer kept cool by refrigerators that were also used to freeze meat and chill down paraffin wax for making objects invisible.

- "Life is No Picnic" – Instant coffee gets off the ground in World War II and Jeeps lead to nylons and stocking machines smashed by Luddites, who were defended by Lord Byron, who meets John Galt in Turkey, avoiding the same blockade that inspires the "Star-Spangled Banner", which was really an English song all about a Greek poet discovered by a publisher whose son-in-law is pals with Joseph Justus Scaliger of chronology fame, whose military boss, Maurice, inspires Gustavus of Sweden, father of the runaway Christina, whose teacher René Descartes' mechanical universe inspires the book about brains by Willis, which is illustrated by the architect of St. Paul's, Christopher Wren, who dabbles in investments like John Law's Louisiana scam that ruins France, and Pierre Beaumarchais, and later the French finance minister Jacques Necker, whose daughter is the opinionated de Stael, whose romantic pals get Thomas Henry Huxley looking into jellyfish so he can defend Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. This demonstrates that "Life is No Picnic".

- "Elementary Stuff" – Alfred Russel Wallace, who studied beetles, Oliver Lodge and telegraphy, a radio designed by Reginald Fessenden, which was used by banana growers, studied by Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, who got the Swiss to use stamps on postcards with cartoons of Gothic houses of parliament, which in turn had been inspired by Johann Gottfried Herder's Romantic movement, inspired by fake Scottish poems. The exiled Scots escaped to North Carolina, producing turpentine, which helped make Chinese lacquer on tinplate, which is for what Jean-Baptiste Colbert had hoped. French navy decorator Pierre Paul Puget, who paints pictures of locations where barometers are the subject of investigation. The weather experimenter, whose brother's writing turns on Swift, whose pal Berkeley has visual theories that Young confirms while decoding ancient Egyptian from examples sketched by pencils invented by French balloonists. The American balloons are used for spying by Allan Pinkerton and his intrepid agent James McParland, who becomes famous in England because of Conan Doyle.

- "A Special Place" – Professor Sir Alec Jeffries of Leicester University in England develops DNA profiling and schlieren photography used by Theodore von Karman to study aerodynamics and Anthony Fokker's airborne machine guns and the Red Baron and geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen and Johann Gottfried Herder's romantic ideas that start in Italy and paintings of actors and lighthouses and the War of Jenkins' Ear and Spanish gold and Alexander Monro and William Cheselden's skeleton drawings and astronomical poetry by friends of fishing aficionados who write books and Charles Cotton and sceptical wine-drinkers called Michel Eyquem, and Edward Jenner's cure for smallpox and J. J. Audubon and American bird painters and devious Russian real estate deals, and as a result in 1872, America gets a special place, the first national park, Yellowstone.

- "Fire from the Sky" – Due to continental drift and Alfred Wegener's passion for mirages, magic images from the sister of King Arthur, whose chivalry supposedly triggers the medieval courtly love answers to adultery, which were in turn inspired by the free love ideas of the mystical Cathars, who lived next to the mystical cabalists who were fascinated with mystic numbers that spark Pico of Mirandola's interest in Hebrew, which then brings trouble for Johann Reuchlin, not helped by his nephew, the Protestant Melanchthon, who had a feud with Osiander, who rewrites the work of Copernicus. Osiander's Italian pal, Dr. Cardano, who cures the asthmatic Archbishop John Hamilton, executed for helping Mary, Queen of Scots, whose lover, the explosive-bearing Earl of Bothwell, ends up in Scandinavia with a friend of astronomer Tycho Brahe, whose assistant, Willem Blaeu, makes maps updated in the first true atlas by the Englishman Dudley, working in Italy for Bernardo Buontalenti, who got opera started, which was a rave success, especially with the French Cardinal Mazarin, whose library inspired the secretary of the English navy, which eventually buys French semaphore, after which Gamble gets the patent for canned food that feeds explorers like Hooker, who transplanted rubber trees to Sri Lanka. As a result of all that, we have rubber to mix with gasoline to make napalm, which is "Fire from the Sky".

- "Hit the Water" – Thanks to napalm, made with palm oil, also used for margarine, stiffened with a process using kieselguhr that comes from plankton living in currents studied by Ballot before observing the Doppler effect that caused Fizeau to measure the speed of light. Fizeau's father-in-law's friend, Prosper Mérimée, who wrote "Carmen"... his friend, Anthony Panizzi, who works at the British Museum, opened to house the collection of Hans Sloane, who treats Lady Montague's smallpox before she sees Turkish tulips, first drawn by Gesner, whose godfather eats sausages and cancels the military contract with France, which was the first to develop military music and choreography, used in a London show by John Gay, whose friend Arbuthnot does statistics that impress the Dutch mathematician who knows Voltaire, who hears from the worm-slicing Lazzaro Spallanzani, who stars in the story by Judge Hoffman, who tries German nationalists who start gymnastics, adopted by the YMCA and the man who started the Red Cross, who need a way to figure out blood types, surgical stitching and the perfusion pump invented by Charles Lindbergh, whose father-in-law's disarmament treaty leads to Graf Spee, Altmark, and the German invasion of Norway and the Allied commandos whose mission was to "Hit the Water".

- "In Touch" – Starting from an attempt for cheaper fusion power using superconductivity, which was discovered by Onnes, with liquid gas provided by Louis-Paul Cailletet, who carried out experiments on a tower built by Gustave Eiffel, who also built the Statue of Liberty with its famous poem by the Jewish activist Emma Lazarus, helped by Oliphant, whose boss Elgin was the son of the man who stole the Elgin Marbles and sold them with the help of royal painter Thomas Lawrence, whose colleague John Hunter had an assistant whose wife's lodger was Benjamin Franklin, who charted the Gulf Stream with a thermometer Fahrenheit borrowed from Ole Rømer, whose friend Picard surveyed Versailles and provided the water for the fountains and the royal gardens and all the trees that inspired Duhamel to write the book on gardening that was read by the architect William Chambers, who hired the Scottish stonemason Thomas Telford, whose idea for London Bridge was turned down by Thomas Young, whose light waves travel in ether, as do Hertz's electricity waves, with which Helmholtz prods a frog to disprove the vitalists, whose leader, Klages, analyses handwriting so individual post codes have to be capital letters to get your mail to a jungle village to keep you "In Touch".

Related works

The first series received a companion book, also by Burke. All three Connections series have been released in their entirety as DVD box sets in the US. The ten episodes of series one were released in Europe (Region 2) on 6 February 2017.

Burke also wrote a recurring column for Scientific American which explored the history of science and ideas, going back and forth through time explaining things on the way and, generally, coming back to the starting point. The columns were collated into a book in 1995 (ISBN:0-316-11672-6).

Burke produced another documentary series called The Day the Universe Changed in 1985, which explored man's concept of how the universe worked in a manner similar to the original Connections.

Richard Hammond's Engineering Connections, shown on BBC2, follows a similar format.

In video games

Connections, a Myst-style computer game with James Burke and others providing video footage and voice acting, was released in 1995.[3] It was a runner-up for Computer Gaming World's award for the best "Classics/Puzzles" game of 1995, which ultimately went to You Don't Know Jack. The editors wrote of Connections, "That you enjoy yourself so much you hardly realize that you're learning is a tribute to the design."[4]

A clip from the episode "Yesterday, Tomorrow and You" appears in the 2016 video game The Witness.

References

- ↑ "Re-Connections: James Burke is Back!". KCSM Community Stations – San Mateo, California. http://www.kcsm.org/tv/catalog/Reconnections/index.htm.

- ↑ This is not the ISBN of the original 1978 book, but those available online March 2017 via used book web sites Connections. Simon and Schuster. 2007. ISBN 9780316116725., and ISBN:978-0743299558, 1998 edition: ISBN:978-0316116817.

- ↑ Connections – MobyGames

- ↑ Staff (June 1996). "The Computer Gaming World 1996 Premier Awards". Computer Gaming World (143): 55, 56, 58, 60, 62, 64, 66, 67.

External links

- Partial series on the Internet Archive

- Complete Series on Internet Archive

- Connections on IMDb

- Connections 2 on IMDb

- Connections 3 on IMDb

- Re-Connections on IMDb

- TV Cream on Connections