Homotopy groups of spheres

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (September 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In the mathematical field of algebraic topology, the homotopy groups of spheres describe how spheres of various dimensions can wrap around each other. They are examples of topological invariants, which reflect, in algebraic terms, the structure of spheres viewed as topological spaces, forgetting about their precise geometry. Unlike homology groups, which are also topological invariants, the homotopy groups are surprisingly complex and difficult to compute.

The n-dimensional unit sphere — called the n-sphere for brevity, and denoted as Sn — generalizes the familiar circle (S1) and the ordinary sphere (S2). The n-sphere may be defined geometrically as the set of points in a Euclidean space of dimension n + 1 located at a unit distance from the origin. The i-th homotopy group πi(Sn) summarizes the different ways in which the i-dimensional sphere Si can be mapped continuously into the n-dimensional sphere Sn. This summary does not distinguish between two mappings if one can be continuously deformed to the other; thus, only equivalence classes of mappings are summarized. An "addition" operation defined on these equivalence classes makes the set of equivalence classes into an abelian group.

The problem of determining πi(Sn) falls into three regimes, depending on whether i is less than, equal to, or greater than n:

- For 0 < i < n, any mapping from Si to Sn is homotopic (i.e., continuously deformable) to a constant mapping, i.e., a mapping that maps all of Si to a single point of Sn. In the smooth case, it follows directly from Sard's Theorem. Therefore the homotopy group is the trivial group.

- When i = n, every map from Sn to itself has a degree that measures how many times the sphere is wrapped around itself. This degree identifies the homotopy group πn(Sn) with the group of integers under addition. For example, every point on a circle can be mapped continuously onto a point of another circle; as the first point is moved around the first circle, the second point may cycle several times around the second circle, depending on the particular mapping.

- The most interesting and surprising results occur when i > n. The first such surprise was the discovery of a mapping called the Hopf fibration, which wraps the 3-sphere S3 around the usual sphere S2 in a non-trivial fashion, and so is not equivalent to a one-point mapping.

The question of computing the homotopy group πn+k(Sn) for positive k turned out to be a central question in algebraic topology that has contributed to development of many of its fundamental techniques and has served as a stimulating focus of research. One of the main discoveries is that the homotopy groups πn+k(Sn) are independent of n for n ≥ k + 2. These are called the stable homotopy groups of spheres and have been computed for values of k up to 90.[1] The stable homotopy groups form the coefficient ring of an extraordinary cohomology theory, called stable cohomotopy theory. The unstable homotopy groups (for n < k + 2) are more erratic; nevertheless, they have been tabulated for k < 20. Most modern computations use spectral sequences, a technique first applied to homotopy groups of spheres by Jean-Pierre Serre. Several important patterns have been established, yet much remains unknown and unexplained.

Background

The study of homotopy groups of spheres builds on a great deal of background material, here briefly reviewed. Algebraic topology provides the larger context, itself built on topology and abstract algebra, with homotopy groups as a basic example.

n-sphere

An ordinary sphere in three-dimensional space—the surface, not the solid ball—is just one example of what a sphere means in topology. Geometry defines a sphere rigidly, as a shape. Here are some alternatives.

- Implicit surface: x20 + x21 + x22 = 1

- This is the set of points in 3-dimensional Euclidean space found exactly one unit away from the origin. It is called the 2-sphere, S2, for reasons given below. The same idea applies for any dimension n; the equation x20 + x21 + ⋯ + x2n = 1 produces the n-sphere as a geometric object in (n + 1)-dimensional space. For example, the 1-sphere S1 is a circle.[2]

- Disk with collapsed rim: written in topology as D2/S1

- This construction moves from geometry to pure topology. The disk D2 is the region contained by a circle, described by the inequality x20 + x21 ≤ 1, and its rim (or "boundary") is the circle S1, described by the equality x20 + x21 = 1. If a balloon is punctured and spread flat it produces a disk; this construction repairs the puncture, like pulling a drawstring. The slash, pronounced "modulo", means to take the topological space on the left (the disk) and in it join together as one all the points on the right (the circle). The region is 2-dimensional, which is why topology calls the resulting topological space a 2-sphere. Generalized, Dn/Sn−1 produces Sn. For example, D1 is a line segment, and the construction joins its ends to make a circle. An equivalent description is that the boundary of an n-dimensional disk is glued to a point, producing a CW complex.[3]

- Suspension of equator: written in topology as ΣS1

- This construction, though simple, is of great theoretical importance. Take the circle S1 to be the equator, and sweep each point on it to one point above (the North Pole), producing the northern hemisphere, and to one point below (the South Pole), producing the southern hemisphere. For each positive integer n, the n-sphere x20 + x21 + ⋯ + x2n = 1 has as equator the (n − 1)-sphere x20 + x21 + ⋯ + x2n−1 = 1, and the suspension ΣSn−1 produces Sn.[4]

Some theory requires selecting a fixed point on the sphere, calling the pair (sphere, point) a pointed sphere. For some spaces the choice matters, but for a sphere all points are equivalent so the choice is a matter of convenience.[5] For spheres constructed as a repeated suspension, the point (1, 0, 0, ..., 0), which is on the equator of all the levels of suspension, works well; for the disk with collapsed rim, the point resulting from the collapse of the rim is another obvious choice.

Homotopy group

The distinguishing feature of a topological space is its continuity structure, formalized in terms of open sets or neighborhoods. A continuous map is a function between spaces that preserves continuity. A homotopy is a continuous path between continuous maps; two maps connected by a homotopy are said to be homotopic.[6] The idea common to all these concepts is to discard variations that do not affect outcomes of interest. An important practical example is the residue theorem of complex analysis, where "closed curves" are continuous maps from the circle into the complex plane, and where two closed curves produce the same integral result if they are homotopic in the topological space consisting of the plane minus the points of singularity.[7]

The first homotopy group, or fundamental group, π1(X) of a (path connected) topological space X thus begins with continuous maps from a pointed circle (S1,s) to the pointed space (X,x), where maps from one pair to another map s into x. These maps (or equivalently, closed curves) are grouped together into equivalence classes based on homotopy (keeping the "base point" x fixed), so that two maps are in the same class if they are homotopic. Just as one point is distinguished, so one class is distinguished: all maps (or curves) homotopic to the constant map S1↦x are called null homotopic. The classes become an abstract algebraic group with the introduction of addition, defined via an "equator pinch". This pinch maps the equator of a pointed sphere (here a circle) to the distinguished point, producing a "bouquet of spheres" — two pointed spheres joined at their distinguished point. The two maps to be added map the upper and lower spheres separately, agreeing on the distinguished point, and composition with the pinch gives the sum map.[8]

More generally, the i-th homotopy group, πi(X) begins with the pointed i-sphere (Si, s), and otherwise follows the same procedure. The null homotopic class acts as the identity of the group addition, and for X equal to Sn (for positive n) — the homotopy groups of spheres — the groups are abelian and finitely generated. If for some i all maps are null homotopic, then the group πi consists of one element, and is called the trivial group.

A continuous map between two topological spaces induces a group homomorphism between the associated homotopy groups. In particular, if the map is a continuous bijection (a homeomorphism), so that the two spaces have the same topology, then their i-th homotopy groups are isomorphic for all i. However, the real plane has exactly the same homotopy groups as a solitary point (as does a Euclidean space of any dimension), and the real plane with a point removed has the same groups as a circle, so groups alone are not enough to distinguish spaces. Although the loss of discrimination power is unfortunate, it can also make certain computations easier.[citation needed]

Low-dimensional examples

The low-dimensional examples of homotopy groups of spheres provide a sense of the subject, because these special cases can be visualized in ordinary 3-dimensional space. However, such visualizations are not mathematical proofs, and do not capture the possible complexity of maps between spheres.

π1(S1) = Z

The simplest case concerns the ways that a circle (1-sphere) can be wrapped around another circle. This can be visualized by wrapping a rubber band around one's finger: it can be wrapped once, twice, three times and so on. The wrapping can be in either of two directions, and wrappings in opposite directions will cancel out after a deformation. The homotopy group π1(S1) is therefore an infinite cyclic group, and is isomorphic to the group Z of integers under addition: a homotopy class is identified with an integer by counting the number of times a mapping in the homotopy class wraps around the circle. This integer can also be thought of as the winding number of a loop around the origin in the plane.[9]

The identification (a group isomorphism) of the homotopy group with the integers is often written as an equality: thus π1(S1) = Z.[10]

π2(S2) = Z

Mappings from a 2-sphere to a 2-sphere can be visualized as wrapping a plastic bag around a ball and then sealing it. The sealed bag is topologically equivalent to a 2-sphere, as is the surface of the ball. The bag can be wrapped more than once by twisting it and wrapping it back over the ball. (There is no requirement for the continuous map to be injective and so the bag is allowed to pass through itself.) The twist can be in one of two directions and opposite twists can cancel out by deformation. The total number of twists after cancellation is an integer, called the degree of the mapping. As in the case mappings from the circle to the circle, this degree identifies the homotopy group with the group of integers, Z. These two results generalize: for all n > 0, πn(Sn) = Z (see below).

π1(S2) = 0

Any continuous mapping from a circle to an ordinary sphere can be continuously deformed to a one-point mapping, and so its homotopy class is trivial. One way to visualize this is to imagine a rubber-band wrapped around a frictionless ball: the band can always be slid off the ball. The homotopy group is therefore a trivial group, with only one element, the identity element, and so it can be identified with the subgroup of Z consisting only of the number zero. This group is often denoted by 0. Showing this rigorously requires more care, however, due to the existence of space-filling curves.[11]

This result generalizes to higher dimensions. All mappings from a lower-dimensional sphere into a sphere of higher dimension are similarly trivial: if i < n, then πi(Sn) = 0. This can be shown as a consequence of the cellular approximation theorem.[12]

π2(S1) = 0

All the interesting cases of homotopy groups of spheres involve mappings from a higher-dimensional sphere onto one of lower dimension. Unfortunately, the only example which can easily be visualized is not interesting: there are no nontrivial mappings from the ordinary sphere to the circle. Hence, π2(S1) = 0. This is because S1 has the real line as its universal cover which is contractible (it has the homotopy type of a point). In addition, because S2 is simply connected, by the lifting criterion,[13] any map from S2 to S1 can be lifted to a map into the real line and the nullhomotopy descends to the downstairs space (via composition).

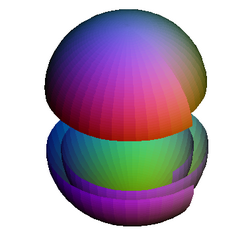

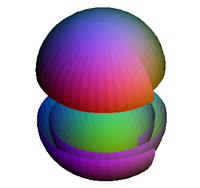

π3(S2) = Z

The first nontrivial example with i > n concerns mappings from the 3-sphere to the ordinary 2-sphere, and was discovered by Heinz Hopf, who constructed a nontrivial map from S3 to S2, now known as the Hopf fibration.[14] This map generates the homotopy group π3(S2) = Z.[15]

History

In the late 19th century Camille Jordan introduced the notion of homotopy and used the notion of a homotopy group, without using the language of group theory.[16] A more rigorous approach was adopted by Henri Poincaré in his 1895 set of papers Analysis situs where the related concepts of homology and the fundamental group were also introduced.[17]

Higher homotopy groups were first defined by Eduard Čech in 1932.[18] (His first paper was withdrawn on the advice of Pavel Sergeyevich Alexandrov and Heinz Hopf, on the grounds that the groups were commutative so could not be the right generalizations of the fundamental group.) Witold Hurewicz is also credited with the introduction of higher homotopy groups in his 1935 paper.[19] An important method for calculating the various groups is the concept of stable algebraic topology, which finds properties that are independent of the dimensions. Typically these only hold for larger dimensions. The first such result was Hans Freudenthal's suspension theorem, published in 1937. Stable algebraic topology flourished between 1945 and 1966 with many important results.[19] In 1953 George W. Whitehead showed that there is a metastable range for the homotopy groups of spheres. Jean-Pierre Serre used spectral sequences to show that most of these groups are finite, the exceptions being πn(Sn) and π4n−1(S2n). Others who worked in this area included José Adem, Hiroshi Toda, Frank Adams, J. Peter May, Mark Mahowald, Daniel Isaksen, Guozhen Wang, and Zhouli Xu. The stable homotopy groups πn+k(Sn) are known for k up to 90, and, as of 2023, unknown for larger k.[1]

General theory

As noted already, when i is less than n, πi(Sn) = 0, the trivial group. The reason is that a continuous mapping from an i-sphere to an n-sphere with i < n can always be deformed so that it is not surjective. Consequently, its image is contained in Sn with a point removed; this is a contractible space, and any mapping to such a space can be deformed into a one-point mapping.[12]

When i = n, πn(Sn) = Z, the infinite cyclic group, generated by the identity map from the n-sphere to itself. It follows from the definition of homotopy groups that the identity map and its multiples are elements of πn(Sn). That these are the only elements can be shown using the Freudenthal suspension theorem, which relates the homotopy groups of a space and its suspension. In the case of spheres, the suspension of an n-sphere is an (n+1)-sphere, and the suspension theorem states that there is a group homomorphism πi(Sn) → πi+1(Sn+1) which is an isomorphism for all i < 2n-1 and is surjective for i = 2n-1. This implies that there is a sequence of group homomorphisms

in which the first homomorphism is a surjection and the rest are isomorphisms. As noted already, π1(S1) = Z, and π2(S2) contains a copy of Z generated by the identity map, so the fact that there is a surjective homomorphism from π1(S1) to π2(S2) implies that π2(S2) = Z. The rest of the homomorphisms in the sequence are isomorphisms, so πn(Sn) = Z for all n.[20]

The homology groups Hi(Sn), with i > n, are all trivial. It therefore came as a great surprise historically that the corresponding homotopy groups are not trivial in general.[citation needed] This is the case that is of real importance: the higher homotopy groups πi(Sn), for i > n, are surprisingly complex and difficult to compute, and the effort to compute them has generated a significant amount of new mathematics.[citation needed]

Table

The following table gives an idea of the complexity of the higher homotopy groups even for spheres of dimension 8 or less. In this table, the entries are either a) the trivial group 0, the infinite cyclic group Z, b) the finite cyclic groups of order n (written as Zn), or c) the direct products of such groups (written, for example, as Z24×Z3 or Z22 = Z2×Z2). Extended tables of homotopy groups of spheres are given at the end of the article.

| π1 | π2 | π3 | π4 | π5 | π6 | π7 | π8 | π9 | π10 | π11 | π12 | π13 | π14 | π15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Z | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S2 | 0 | Z | Z | Z2 | Z2 | Z12 | Z2 | Z2 | Z3 | Z15 | Z2 | Z22 | Z12×Z2 | Z84×Z22 | Z22 |

| S3 | 0 | 0 | Z | Z2 | Z2 | Z12 | Z2 | Z2 | Z3 | Z15 | Z2 | Z22 | Z12×Z2 | Z84×Z22 | Z22 |

| S4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Z | Z2 | Z2 | Z×Z12 | Z22 | Z22 | Z24×Z3 | Z15 | Z2 | Z32 | Z120×Z12×Z2 | Z84×Z52 |

| S5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Z | Z2 | Z2 | Z24 | Z2 | Z2 | Z2 | Z30 | Z2 | Z32 | Z72×Z2 |

| S6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Z | Z2 | Z2 | Z24 | 0 | Z | Z2 | Z60 | Z24×Z2 | Z32 |

| S7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Z | Z2 | Z2 | Z24 | 0 | 0 | Z2 | Z120 | Z32 |

| S8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Z | Z2 | Z2 | Z24 | 0 | 0 | Z2 | Z×Z120 |

The first row of this table is straightforward. The homotopy groups πi(S1) of the 1-sphere are trivial for i > 1, because the universal covering space, , which has the same higher homotopy groups, is contractible.[21]

Beyond the first row, the higher homotopy groups (i > n) appear to be chaotic, but in fact there are many patterns, some obvious and some very subtle.

- The groups below the jagged black line are constant along the diagonals (as indicated by the red, green and blue coloring).

- Most of the groups are finite. The only infinite groups are either on the main diagonal or immediately above the jagged line (highlighted in yellow).

- The second and third rows of the table are the same starting in the third column (i.e., πi(S2) = πi(S3) for i ≥ 3). This isomorphism is induced by the Hopf fibration S3 → S2.

- For n = 2, 3, 4, 5 and i ≥ n the homotopy groups πi(Sn) do not vanish. However, πn+4(Sn) = 0 for n ≥ 6.

These patterns follow from many different theoretical results.[citation needed]

Stable and unstable groups

The fact that the groups below the jagged line in the table above are constant along the diagonals is explained by the suspension theorem of Hans Freudenthal, which implies that the suspension homomorphism from πn+k(Sn) to πn+k+1(Sn+1) is an isomorphism for n > k + 1. The groups πn+k(Sn) with n > k + 1 are called the stable homotopy groups of spheres, and are denoted πSk: they are finite abelian groups for k ≠ 0, and have been computed in numerous cases, although the general pattern is still elusive.[22] For n ≤ k+1, the groups are called the unstable homotopy groups of spheres.[citation needed]

Hopf fibrations

The classical Hopf fibration is a fiber bundle:

The general theory of fiber bundles F → E → B shows that there is a long exact sequence of homotopy groups

For this specific bundle, each group homomorphism πi(S1) → πi(S3), induced by the inclusion S1 → S3, maps all of πi(S1) to zero, since the lower-dimensional sphere S1 can be deformed to a point inside the higher-dimensional one S3. This corresponds to the vanishing of π1(S3). Thus the long exact sequence breaks into short exact sequences,

Since Sn+1 is a suspension of Sn, these sequences are split by the suspension homomorphism πi−1(S1) → πi(S2), giving isomorphisms

Since πi−1(S1) vanishes for i at least 3, the first row shows that πi(S2) and πi(S3) are isomorphic whenever i is at least 3, as observed above.

The Hopf fibration may be constructed as follows: pairs of complex numbers (z0,z1) with |z0|2 + |z1|2 = 1 form a 3-sphere, and their ratios z0/z1 cover the complex plane plus infinity, a 2-sphere. The Hopf map S3 → S2 sends any such pair to its ratio.[citation needed]

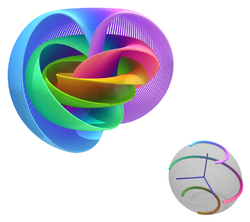

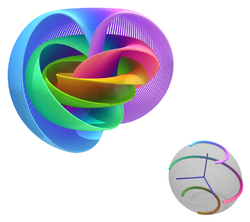

Similarly (in addition to the Hopf fibration , where the bundle projection is a double covering), there are generalized Hopf fibrations

constructed using pairs of quaternions or octonions instead of complex numbers.[23] Here, too, π3(S7) and π7(S15) are zero. Thus the long exact sequences again break into families of split short exact sequences, implying two families of relations.

The three fibrations have base space Sn with n = 2m, for m = 1, 2, 3. A fibration does exist for S1 (m = 0) as mentioned above, but not for S16 (m = 4) and beyond. Although generalizations of the relations to S16 are often true, they sometimes fail; for example,

Thus there can be no fibration

the first non-trivial case of the Hopf invariant one problem, because such a fibration would imply that the failed relation is true.[citation needed]

Framed cobordism

Homotopy groups of spheres are closely related to cobordism classes of manifolds. In 1938 Lev Pontryagin established an isomorphism between the homotopy group πn+k(Sn) and the group Ωframedk(Sn+k) of cobordism classes of differentiable k-submanifolds of Sn+k which are "framed", i.e. have a trivialized normal bundle. Every map f : Sn+k → Sn is homotopic to a differentiable map with Mk = f−1(1, 0, ..., 0) ⊂ Sn+k a framed k-dimensional submanifold. For example, πn(Sn) = Z is the cobordism group of framed 0-dimensional submanifolds of Sn, computed by the algebraic sum of their points, corresponding to the degree of maps f : Sn → Sn. The projection of the Hopf fibration S3 → S2 represents a generator of π3(S2) = Ωframed1(S3) = Z which corresponds to the framed 1-dimensional submanifold of S3 defined by the standard embedding S1 ⊂ S3 with a nonstandard trivialization of the normal 2-plane bundle. Until the advent of more sophisticated algebraic methods in the early 1950s (Serre) the Pontrjagin isomorphism was the main tool for computing the homotopy groups of spheres. In 1954 the Pontrjagin isomorphism was generalized by René Thom to an isomorphism expressing other groups of cobordism classes (e.g. of all manifolds) as homotopy groups of spaces and spectra. In more recent work the argument is usually reversed, with cobordism groups computed in terms of homotopy groups.[24]

Finiteness and torsion

In 1951, Jean-Pierre Serre showed that homotopy groups of spheres are all finite except for those of the form πn(Sn) or π4n−1(S2n) (for positive n), when the group is the product of the infinite cyclic group with a finite abelian group.[25] In particular the homotopy groups are determined by their p-components for all primes p. The 2-components are hardest to calculate, and in several ways behave differently from the p-components for odd primes.[citation needed]

In the same paper, Serre found the first place that p-torsion occurs in the homotopy groups of n dimensional spheres, by showing that πn+k(Sn) has no p-torsion if k < 2p − 3, and has a unique subgroup of order p if n ≥ 3 and k = 2p − 3. The case of 2-dimensional spheres is slightly different: the first p-torsion occurs for k = 2p − 3 + 1. In the case of odd torsion there are more precise results; in this case there is a big difference between odd and even dimensional spheres. If p is an odd prime and n = 2i + 1, then elements of the p-component of πn+k(Sn) have order at most pi.[26] This is in some sense the best possible result, as these groups are known to have elements of this order for some values of k.[27] Furthermore, the stable range can be extended in this case: if n is odd then the double suspension from πk(Sn) to πk+2(Sn+2) is an isomorphism of p-components if k < p(n + 1) − 3, and an epimorphism if equality holds.[28] The p-torsion of the intermediate group πk+1(Sn+1) can be strictly larger.[citation needed]

The results above about odd torsion only hold for odd-dimensional spheres: for even-dimensional spheres, the James fibration gives the torsion at odd primes p in terms of that of odd-dimensional spheres,

(where (p) means take the p-component).[29] This exact sequence is similar to the ones coming from the Hopf fibration; the difference is that it works for all even-dimensional spheres, albeit at the expense of ignoring 2-torsion. Combining the results for odd and even dimensional spheres shows that much of the odd torsion of unstable homotopy groups is determined by the odd torsion of the stable homotopy groups.[citation needed]

For stable homotopy groups there are more precise results about p-torsion. For example, if k < 2p(p − 1) − 2 for a prime p then the p-primary component of the stable homotopy group πSk vanishes unless k + 1 is divisible by 2(p − 1), in which case it is cyclic of order p.[30]

The J-homomorphism

An important subgroup of πn+k(Sn), for k ≥ 2, is the image of the J-homomorphism J : πk(SO(n)) → πn+k(Sn), where SO(n) denotes the special orthogonal group.[31] In the stable range n ≥ k + 2, the homotopy groups πk(SO(n)) only depend on k (mod 8). This period 8 pattern is known as Bott periodicity, and it is reflected in the stable homotopy groups of spheres via the image of the J-homomorphism which is:

- a cyclic group of order 2 if k is congruent to 0 or 1 modulo 8;

- trivial if k is congruent to 2, 4, 5, or 6 modulo 8; and

- a cyclic group of order equal to the denominator of B2m/4m, where B2m is a Bernoulli number, if k = 4m − 1 ≡ 3 (mod 4).

This last case accounts for the elements of unusually large finite order in πn+k(Sn) for such values of k. For example, the stable groups πn+11(Sn) have a cyclic subgroup of order 504, the denominator of B6/12 = 1/504.[citation needed]

The stable homotopy groups of spheres are the direct sum of the image of the J-homomorphism, and the kernel of the Adams e-invariant, a homomorphism from these groups to . Roughly speaking, the image of the J-homomorphism is the subgroup of "well understood" or "easy" elements of the stable homotopy groups. These well understood elements account for most elements of the stable homotopy groups of spheres in small dimensions. The quotient of πSn by the image of the J-homomorphism is considered to be the "hard" part of the stable homotopy groups of spheres (Adams 1966). (Adams also introduced certain order 2 elements μn of πSn for n ≡ 1 or 2 (mod 8), and these are also considered to be "well understood".) Tables of homotopy groups of spheres sometimes omit the "easy" part im(J) to save space.[citation needed]

Ring structure

The direct sum

of the stable homotopy groups of spheres is a supercommutative graded ring, where multiplication is given by composition of representing maps, and any element of non-zero degree is nilpotent;[32] the nilpotence theorem on complex cobordism implies Nishida's theorem.[citation needed]

Example: If η is the generator of πS1 (of order 2), then η2 is nonzero and generates πS2, and η3 is nonzero and 12 times a generator of πS3, while η4 is zero because the group πS4 is trivial.[citation needed]

If f and g and h are elements of πS* with f g = 0 and g⋅h = 0, there is a Toda bracket ⟨f, g, h⟩ of these elements.[33] The Toda bracket is not quite an element of a stable homotopy group, because it is only defined up to addition of products of certain other elements. Hiroshi Toda used the composition product and Toda brackets to label many of the elements of homotopy groups. There are also higher Toda brackets of several elements, defined when suitable lower Toda brackets vanish. This parallels the theory of Massey products in cohomology.[citation needed] Every element of the stable homotopy groups of spheres can be expressed using composition products and higher Toda brackets in terms of certain well known elements, called Hopf elements.[34]

Computational methods

If X is any finite simplicial complex with finite fundamental group, in particular if X is a sphere of dimension at least 2, then its homotopy groups are all finitely generated abelian groups. To compute these groups, they are often factored into their p-components for each prime p, and calculating each of these p-groups separately. The first few homotopy groups of spheres can be computed using ad hoc variations of the ideas above; beyond this point, most methods for computing homotopy groups of spheres are based on spectral sequences.[35] This is usually done by constructing suitable fibrations and taking the associated long exact sequences of homotopy groups; spectral sequences are a systematic way of organizing the complicated information that this process generates.[citation needed]

- "The method of killing homotopy groups", due to Cartan and Serre (1952a, 1952b) involves repeatedly using the Hurewicz theorem to compute the first non-trivial homotopy group and then killing (eliminating) it with a fibration involving an Eilenberg–MacLane space. In principle this gives an effective algorithm for computing all homotopy groups of any finite simply connected simplicial complex, but in practice it is too cumbersome to use for computing anything other than the first few nontrivial homotopy groups as the simplicial complex becomes much more complicated every time one kills a homotopy group.

- The Serre spectral sequence was used by Serre to prove some of the results mentioned previously. He used the fact that taking the loop space of a well behaved space shifts all the homotopy groups down by 1, so the nth homotopy group of a space X is the first homotopy group of its (n−1)-fold repeated loop space, which is equal to the first homology group of the (n−1)-fold loop space by the Hurewicz theorem. This reduces the calculation of homotopy groups of X to the calculation of homology groups of its repeated loop spaces. The Serre spectral sequence relates the homology of a space to that of its loop space, so can sometimes be used to calculate the homology of loop spaces. The Serre spectral sequence tends to have many non-zero differentials, which are hard to control, and too many ambiguities appear for higher homotopy groups. Consequently, it has been superseded by more powerful spectral sequences with fewer non-zero differentials, which give more information.[citation needed]

- The EHP spectral sequence can be used to compute many homotopy groups of spheres; it is based on some fibrations used by Toda in his calculations of homotopy groups.[36][33]

- The classical Adams spectral sequence has E2 term given by the Ext groups Ext∗,∗A(p)(Zp, Zp) over the mod p Steenrod algebra A(p), and converges to something closely related to the p-component of the stable homotopy groups. The initial terms of the Adams spectral sequence are themselves quite hard to compute: this is sometimes done using an auxiliary spectral sequence called the May spectral sequence.[37]

- At the odd primes, the Adams–Novikov spectral sequence is a more powerful version of the Adams spectral sequence replacing ordinary cohomology mod p with a generalized cohomology theory, such as complex cobordism or, more usually, a piece of it called Brown–Peterson cohomology. The initial term is again quite hard to calculate; to do this one can use the chromatic spectral sequence.[38]

- A variation of this last approach uses a backwards version of the Adams–Novikov spectral sequence for Brown–Peterson cohomology: the limit is known, and the initial terms involve unknown stable homotopy groups of spheres that one is trying to find.[39]

- The motivic Adams spectral sequence converges to the motivic stable homotopy groups of spheres. By comparing the motivic one over the complex numbers with the classical one, Isaksen gives rigorous proof of computations up to the 59-stem. In particular, Isaksen computes the Coker J of the 56-stem is 0, and therefore by the work of Kervaire-Milnor, the sphere S56 has a unique smooth structure.[40]

- The Kahn–Priddy map induces a map of Adams spectral sequences from the suspension spectrum of infinite real projective space to the sphere spectrum. It is surjective on the Adams E2 page on positive stems. Wang and Xu develops a method using the Kahn–Priddy map to deduce Adams differentials for the sphere spectrum inductively. They give detailed argument for several Adams differentials and compute the 60 and 61-stem. A geometric corollary of their result is the sphere S61 has a unique smooth structure, and it is the last odd dimensional one – the only ones are S1, S3, S5, and S61.[41]

- The motivic cofiber of τ method is so far the most efficient method at the prime 2. The class τ is a map between motivic spheres. The Gheorghe–Wang–Xu theorem identifies the motivic Adams spectral sequence for the cofiber of τ as the algebraic Novikov spectral sequence for BP*, which allows one to deduce motivic Adams differentials for the cofiber of τ from purely algebraic data. One can then pullback these motivic Adams differentials to the motivic sphere, and then use the Betti realization functor to push forward them to the classical sphere.[42] Using this method, (Isaksen Wang) computes up to the 90-stem.[1]

The computation of the homotopy groups of S2 has been reduced to a combinatorial group theory question. (Berrick Cohen) identify these homotopy groups as certain quotients of the Brunnian braid groups of S2. Under this correspondence, every nontrivial element in πn(S2) for n > 2 may be represented by a Brunnian braid over S2 that is not Brunnian over the disk D2. For example, the Hopf map S3 → S2 corresponds to the Borromean rings.[43]

Applications

- The winding number (corresponding to an integer of π1(S1) = Z) can be used to prove the fundamental theorem of algebra, which states that every non-constant complex polynomial has a zero.[44]

- The fact that πn−1(Sn−1) = Z implies the Brouwer fixed point theorem that every continuous map from the n-dimensional ball to itself has a fixed point.[45]

- The stable homotopy groups of spheres are important in singularity theory, which studies the structure of singular points of smooth maps or algebraic varieties. Such singularities arise as critical points of smooth maps from to . The geometry near a critical point of such a map can be described by an element of πm−1(Sn−1), by considering the way in which a small m − 1 sphere around the critical point maps into a topological n − 1 sphere around the critical value.[citation needed]

- The fact that the third stable homotopy group of spheres is cyclic of order 24, first proved by Vladimir Rokhlin, implies Rokhlin's theorem that the signature of a compact smooth spin 4-manifold is divisible by 16.[24]

- Stable homotopy groups of spheres are used to describe the group Θn of h-cobordism classes of oriented homotopy n-spheres (for n ≠ 4, this is the group of smooth structures on n-spheres, up to orientation-preserving diffeomorphism; the non-trivial elements of this group are represented by exotic spheres). More precisely, there is an injective map

- where bPn+1 is the cyclic subgroup represented by homotopy spheres that bound a parallelizable manifold, πSn is the nth stable homotopy group of spheres, and J is the image of the J-homomorphism. This is an isomorphism unless n is of the form 2k − 2, in which case the image has index 1 or 2.[46]

- The groups Θn above, and therefore the stable homotopy groups of spheres, are used in the classification of possible smooth structures on a topological or piecewise linear manifold.[24]

- The Kervaire invariant problem, about the existence of manifolds of Kervaire invariant 1 in dimensions 2k − 2 can be reduced to a question about stable homotopy groups of spheres. For example, knowledge of stable homotopy groups of degree up to 48 has been used to settle the Kervaire invariant problem in dimension 26 − 2 = 62. (This was the smallest value of k for which the question was open at the time.)[47]

- The Barratt–Priddy theorem says that the stable homotopy groups of the spheres can be expressed in terms of the plus construction applied to the classifying space of the symmetric group, leading to an identification of K-theory of the field with one element with stable homotopy groups.[48]

Table of homotopy groups

Tables of homotopy groups of spheres are most conveniently organized by showing πn+k(Sn).

The following table shows many of the groups πn+k(Sn). The stable homotopy groups are highlighted in blue, the unstable ones in red. Each homotopy group is the product of the cyclic groups of the orders given in the table, using the following conventions:[49]

- The entry "⋅" denotes the trivial group.

- Where the entry is an integer, m, the homotopy group is the cyclic group of that order (generally written Zm).

- Where the entry is ∞, the homotopy group is the infinite cyclic group, Z.

- Where entry is a product, the homotopy group is the cartesian product (equivalently, direct sum) of the cyclic groups of those orders. Powers indicate repeated products. (Note that when a and b have no common factor, Za×Zb is isomorphic to Zab.)

Example: π19(S10) = π9+10(S10) = Z×Z2×Z2×Z2, which is denoted by ∞⋅23 in the table.

| Sn → | S0 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | S11 | S12 | S≥13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| π<n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | |

| π0+n(Sn) | 2 | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ |

| π1+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | ∞ | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| π2+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| π3+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 2 | 12 | ∞⋅12 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| π4+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 12 | 2 | 22 | 2 | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ |

| π5+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 2 | 2 | 22 | 2 | ∞ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ |

| π6+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 2 | 3 | 24⋅3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| π7+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 3 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 60 | 120 | ∞⋅120 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 |

| π8+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 15 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 24⋅2 | 23 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| π9+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 2 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 24 | ∞⋅23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| π10+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 22 | 12⋅2 | 120⋅12⋅2 | 72⋅2 | 72⋅2 | 24⋅2 | 242⋅2 | 24⋅2 | 12⋅2 | 6⋅2 | 6 | 6 |

| π11+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 12⋅2 | 84⋅22 | 84⋅25 | 504⋅22 | 504⋅4 | 504⋅2 | 504⋅2 | 504⋅2 | 504 | 504 | ∞⋅504 | 504 |

| π12+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 84⋅22 | 22 | 26 | 23 | 240 | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | 12 | 2 | 22 | See below |

| π13+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 22 | 6 | 24⋅6⋅2 | 6⋅2 | 6 | 6 | 6⋅2 | 6 | 6 | 6⋅2 | 6⋅2 | |

| π14+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 6 | 30 | 2520⋅6⋅2 | 6⋅2 | 12⋅2 | 24⋅4 | 240⋅24⋅4 | 16⋅4 | 16⋅2 | 16⋅2 | 48⋅4⋅2 | |

| π15+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30⋅2 | 60⋅6 | 120⋅23 | 120⋅25 | 240⋅23 | 240⋅22 | 240⋅2 | 240⋅2 | |

| π16+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 30 | 6⋅2 | 62⋅2 | 22 | 504⋅22 | 24 | 27 | 24 | 240⋅2 | 2 | 2 | |

| π17+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 6⋅2 | 12⋅22 | 24⋅12⋅4⋅22 | 4⋅22 | 24 | 24 | 6⋅24 | 24 | 23 | 23 | 24 | |

| π18+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 12⋅22 | 12⋅22 | 120⋅12⋅25 | 24⋅22 | 24⋅6⋅2 | 24⋅2 | 504⋅24⋅2 | 24⋅2 | 24⋅22 | 8⋅4⋅2 | 480⋅42⋅2 | |

| π19+n(Sn) | ⋅ | ⋅ | 12⋅22 | 132⋅2 | 132⋅25 | 264⋅2 | 1056⋅8 | 264⋅2 | 264⋅2 | 264⋅2 | 264⋅6 | 264⋅23 | 264⋅25 |

| Sn → | S13 | S14 | S15 | S16 | S17 | S18 | S19 | S20 | S≥21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| π12+n(Sn) | 2 | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ | ⋅ |

| π13+n(Sn) | 6 | ∞⋅3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| π14+n(Sn) | 16⋅2 | 8⋅2 | 4⋅2 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| π15+n(Sn) | 480⋅2 | 480⋅2 | 480⋅2 | ∞⋅480⋅2 | 480⋅2 | 480⋅2 | 480⋅2 | 480⋅2 | 480⋅2 |

| π16+n(Sn) | 2 | 24⋅2 | 23 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| π17+n(Sn) | 24 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 25 | ∞⋅24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| π18+n(Sn) | 82⋅2 | 82⋅2 | 82⋅2 | 24⋅82⋅2 | 82⋅2 | 8⋅4⋅2 | 8⋅22 | 8⋅2 | 8⋅2 |

| π19+n(Sn) | 264⋅23 | 264⋅4⋅2 | 264⋅22 | 264⋅22 | 264⋅22 | 264⋅2 | 264⋅2 | ∞⋅264⋅2 | 264⋅2 |

Table of stable homotopy groups

The stable homotopy groups πSk are the products of cyclic groups of the infinite or prime power orders shown in the table. (For largely historical reasons, stable homotopy groups are usually given as products of cyclic groups of prime power order, while tables of unstable homotopy groups often give them as products of the smallest number of cyclic groups.) For p > 5, the part of the p-component that is accounted for by the J-homomorphism is cyclic of order p if 2(p − 1) divides k + 1 and 0 otherwise.[50] The mod 8 behavior of the table comes from Bott periodicity via the J-homomorphism, whose image is underlined.

| n → | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| π0+nS | ∞ | 2 | 2 | 8⋅3 | ⋅ | ⋅ | 2 | 16⋅3⋅5 |

| π8+nS | 2⋅2 | 2⋅22 | 2⋅3 | 8⋅9⋅7 | ⋅ | 3 | 22 | 32⋅2⋅3⋅5 |

| π16+nS | 2⋅2 | 2⋅23 | 8⋅2 | 8⋅2⋅3⋅11 | 8⋅3 | 22 | 2⋅2 | 16⋅8⋅2⋅9⋅3⋅5⋅7⋅13 |

| π24+nS | 2⋅2 | 2⋅2 | 22⋅3 | 8⋅3 | 2 | 3 | 2⋅3 | 64⋅22⋅3⋅5⋅17 |

| π32+nS | 2⋅23 | 2⋅24 | 4⋅23 | 8⋅22⋅27⋅7⋅19 | 2⋅3 | 22⋅3 | 4⋅2⋅3⋅5 | 16⋅25⋅3⋅3⋅25⋅11 |

| π40+nS | 2⋅4⋅24⋅3 | 2⋅24 | 8⋅22⋅3 | 8⋅3⋅23 | 8 | 16⋅23⋅9⋅5 | 24⋅3 | 32⋅4⋅23⋅9⋅3⋅5⋅7⋅13 |

| π48+nS | 2⋅4⋅23 | 2⋅2⋅3 | 23⋅3 | 8⋅8⋅2⋅3 | 23⋅3 | 24 | 4⋅2 | 16⋅3⋅3⋅5⋅29 |

| π56+nS | 2 | 2⋅22 | 22 | 8⋅22⋅9⋅7⋅11⋅31 | 4 | ⋅ | 24⋅3 | 128⋅4⋅22⋅3⋅5⋅17 |

| π64+nS | 2⋅4⋅25 | 2⋅4⋅28⋅3 | 8⋅26 | 8⋅4⋅23⋅3 | 23⋅3 | 24 | 42⋅25 | 16⋅8⋅4⋅26⋅27⋅5⋅7⋅13⋅19⋅37 |

| π72+nS | 2⋅27⋅3 | 2⋅26 | 43⋅2⋅3 | 8⋅2⋅9⋅3 | 4⋅22⋅5 | 4⋅25 | 42⋅23⋅3 | 32⋅4⋅26⋅3⋅25⋅11⋅41 |

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Isaksen, Wang & Xu 2023.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. xii.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, Example 0.3, p. 6.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. 129.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. 28.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. 3.

- ↑ Miranda 1995, pp. 123–125.

- ↑ Hu 1959, p. 107.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. 29.

- ↑ See, e.g., Homotopy type theory 2013, Section 8.1, "".

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. 348.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Hatcher 2002, p. 349.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. 61.

- ↑ Hopf 1931.

- ↑ Walschap 2004, p. 90.

- ↑ O'Connor & Robertson 2001.

- ↑ O'Connor & Robertson 1996.

- ↑ Čech 1932, p. 203.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 May 1999a.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. 361.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. 342.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, Stable homotopy groups, pp. 385–393.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Scorpan 2005.

- ↑ Serre 1951.

- ↑ Cohen, Moore & Neisendorfer 1979.

- ↑ Ravenel 2003, p. 4.

- ↑ Serre 1952.

- ↑ Ravenel 2003, p. 25.

- ↑ Fuks 2001.

- ↑ Adams 1966.

- ↑ Nishida 1973.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Toda 1962.

- ↑ Cohen 1968.

- ↑ Ravenel 2003.

- ↑ Mahowald 2001.

- ↑ Ravenel 2003, pp. 67–74.

- ↑ Ravenel 2003, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Kochman 1990.

- ↑ Isaksen 2019.

- ↑ Wang & Xu 2017.

- ↑ Gheorghe, Wang & Xu 2021.

- ↑ Berrick et al. 2006.

- ↑ Fine & Rosenberger 1997.

- ↑ Hatcher 2002, p. 32.

- ↑ Kervaire & Milnor 1963.

- ↑ Barratt, Jones & Mahowald 1984.

- ↑ Deitmar 2006.

- ↑ These tables are based on the table of homotopy groups of spheres in (Toda 1962).

- ↑ Fuks 2001. The 2-components can be found in (Isaksen Wang), and the 3- and 5-components in (Ravenel 2003).

Sources

- Adams, J. Frank (1966), "On the groups J(X) IV", Topology 5 (1): 21–71, doi:10.1016/0040-9383(66)90004-8. See also Adams, J (1968), "Correction", Topology 7 (3): 331, doi:10.1016/0040-9383(68)90010-4.

- Barratt, Michael G.; Jones, John D. S.; Mahowald, Mark E. (1984), "Relations amongst Toda brackets and the Kervaire invariant in dimension 62", Journal of the London Mathematical Society 30 (3): 533–550, doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-30.3.533.

- Berrick, A. J.; Cohen, Frederick R.; Wong, Yan Loi; Wu, Jie (2006), "Configurations, braids, and homotopy groups", Journal of the American Mathematical Society 19 (2): 265–326, doi:10.1090/S0894-0347-05-00507-2, http://www.math.nus.edu.sg/~matwujie/publications.html.

- Cartan, Henri; Serre, Jean-Pierre (1952a), "Espaces fibrés et groupes d'homotopie. I. Constructions générales", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série I (Paris) 234: 288–290, ISSN 0764-4442.

- Cartan, Henri; Serre, Jean-Pierre (1952b), "Espaces fibrés et groupes d'homotopie. II. Applications", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série I (Paris) 234: 393–395, ISSN 0764-4442.

- Cohen, Frederick R.; Moore, John C.; Neisendorfer, Joseph A. (November 1979), "The double suspension and exponents of the homotopy groups of spheres", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series 110 (3): 549–565, doi:10.2307/1971238.

- Cohen, Joel M. (1968), "The decomposition of stable homotopy", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series 87 (2): 305–320, doi:10.2307/1970586, PMID 16591550.

- Deitmar, Anton (2006), "Remarks on zeta functions and K-theory over F1", Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series A, Mathematical Sciences 82 (8): 141–146, doi:10.3792/pjaa.82.141, ISSN 0386-2194, http://projecteuclid.org/getRecord?id=euclid.pja/1162820095.

- Fine, Benjamin; Rosenberger, Gerhard (1997), "8.1 Winding Number and Proof Five", The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag, New York, pp. 134–136, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1928-6, ISBN 0-387-94657-8

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Spheres, homotopy groups of the", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=s/s086650.

- Hu, Sze-tsen (1959), Homotopy theory, Pure and Applied Mathematics, 8, New York & London: Academic Press

- Isaksen, Daniel C. (2019), "Stable Stems", Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society 262 (1269), doi:10.1090/memo/1269, ISBN 978-1-4704-3788-6.

- Isaksen, Daniel C.; Wang, Guozhen; Xu, Zhouli (2023), "Stable homotopy groups of spheres: from dimension 0 to 90", Publications mathématiques de l'IHÉS 137: 107–243, doi:10.1007/s10240-023-00139-1.

- Kervaire, Michel A.; Milnor, John W. (1963), "Groups of homotopy spheres: I", Annals of Mathematics 77 (3): 504–537, doi:10.2307/1970128.

- Kochman, Stanley O. (1990), Stable homotopy groups of spheres. A computer-assisted approach, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 1423, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/BFb0083795, ISBN 978-3-540-52468-7 Also see the corrections in (Kochman Mahowald)

- Kochman, Stanley O.; Mahowald, Mark E. (1995), "On the computation of stable stems", The Čech centennial (Boston, MA, 1993), Contemporary Mathematics, 181, Providence, R.I.: Amer. Math. Soc., pp. 299–316, ISBN 978-0-8218-0296-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=nEaGVNx2MsoC&pg=PA299

- Mahowald, Mark (1998), "Toward a global understanding of π∗(Sn)", Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians (Berlin, 1998), Documenta Mathematica, Extra Volume, II, pp. 465–472, http://www.emis.de/journals/DMJDMV/xvol-icm/06/Mahowald.MAN.html

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "EHP spectral sequence", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=E/e110020.

- Milnor, John W. (2011), "Differential topology forty-six years later", Notices of the American Mathematical Society 58 (6): 804–809, https://www.ams.org/notices/201106/rtx110600804p.pdf

- Miranda, Rick (1995), Algebraic curves and Riemann surfaces, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, 5, Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, doi:10.1090/gsm/005, ISBN 0-8218-0268-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=aN4bfzgHvvkC&pg=PA123

- "The nilpotency of elements of the stable homotopy groups of spheres", Journal of the Mathematical Society of Japan 25 (4): 707–732, 1973, doi:10.2969/jmsj/02540707, ISSN 0025-5645.

- Pontrjagin, Lev, Smooth manifolds and their applications in homotopy theory American Mathematical Society Translations, Ser. 2, Vol. 11, pp. 1–114 (1959)

- Ravenel, Douglas C. (2003), Complex cobordism and stable homotopy groups of spheres (2nd ed.), AMS Chelsea, ISBN 978-0-8218-2967-7, http://www.math.rochester.edu/people/faculty/doug/mu.html.

- Scorpan, Alexandru (2005), The wild world of 4-manifolds, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-3749-8.

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1951), "Homologie singulière des espaces fibrés. Applications", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series 54 (3): 425–505, doi:10.2307/1969485.

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1952), "Sur la suspension de Freudenthal", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série I (Paris) 234: 1340–1342, ISSN 0764-4442.

- Toda, Hirosi (1962), Composition methods in homotopy groups of spheres, Annals of Mathematics Studies, 49, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-09586-8.

- Walschap, Gerard (2004), "Chapter 3: Homotopy groups and bundles over spheres", Metric structures in differential geometry, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 224, Springer-Verlag, New York, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-21826-7, ISBN 0-387-20430-X

- Wang, Guozhen; Xu, Zhouli (2017), "The triviality of the 61-stem in the stable homotopy groups of spheres", Annals of Mathematics 186 (2): 501–580, doi:10.4007/annals.2017.186.2.3.

- Gheorghe, Bogdan; Wang, Guozhen; Xu, Zhouli (2021), "The special fiber of the motivic deformation of the stable homotopy category is algebraic", Acta Mathematica 226 (2): 319–407, doi:10.4310/ACTA.2021.v226.n2.a2.

- Homotopy type theory—univalent foundations of mathematics, The Univalent Foundations Program and Institute for Advanced Study, 2013, https://homotopytypetheory.org/book/

General algebraic topology references

- Hatcher, Allen (2002), Algebraic Topology, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-79540-1, https://pi.math.cornell.edu/~hatcher/AT/ATpage.html.

- May (1999b), A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology, Chicago lectures in mathematics (revised ed.), University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-51183-2, http://www.math.uchicago.edu/~may/CONCISE.

Historical papers

- Čech, Eduard (1932), "Höherdimensionale Homotopiegruppen", Verhandlungen des Internationalen Mathematikerkongress, Zürich.

- Hopf, Heinz (1931), "Über die Abbildungen der dreidimensionalen Sphäre auf die Kugelfläche", Mathematische Annalen 104 (1): 637–665, doi:10.1007/BF01457962, http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?GDZPPN002274760.

- May (1999a), "Stable Algebraic Topology 1945–1966", in I. M. James, History of Topology, Elsevier Science, pp. 665–723, ISBN 978-0-444-82375-5, http://hopf.math.purdue.edu/cgi-bin/generate?/May/history.

External links

- Baez, John (21 April 1997), This week's finds in mathematical physics 102, http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/week102.html, retrieved 2007-10-09

- Hatcher, Allen, Stable homotopy groups of spheres, https://pi.math.cornell.edu/~hatcher/stemfigs/stems.pdf, retrieved 2007-10-20

- O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (1996), A history of Topology, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Topology_in_mathematics.html, retrieved 2007-11-14 in MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (2001), Marie Ennemond Camille Jordan, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Jordan.html, retrieved 2007-11-14 in MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

|