Hurwitz's automorphisms theorem

In mathematics, Hurwitz's automorphisms theorem bounds the order of the group of automorphisms, via orientation-preserving conformal mappings, of a compact Riemann surface of genus g > 1, stating that the number of such automorphisms cannot exceed 84(g − 1). A group for which the maximum is achieved is called a Hurwitz group, and the corresponding Riemann surface a Hurwitz surface. Because compact Riemann surfaces are synonymous with non-singular complex projective algebraic curves, a Hurwitz surface can also be called a Hurwitz curve.[1] The theorem is named after Adolf Hurwitz, who proved it in (Hurwitz 1893).

Hurwitz's bound also holds for algebraic curves over a field of characteristic 0, and over fields of positive characteristic p>0 for groups whose order is coprime to p, but can fail over fields of positive characteristic p>0 when p divides the group order. For example, the double cover of the projective line y2 = xp −x branched at all points defined over the prime field has genus g=(p−1)/2 but is acted on by the group SL2(p) of order p3−p.

Interpretation in terms of hyperbolicity

One of the fundamental themes in differential geometry is a trichotomy between the Riemannian manifolds of positive, zero, and negative curvature K. It manifests itself in many diverse situations and on several levels. In the context of compact Riemann surfaces X, via the Riemann uniformization theorem, this can be seen as a distinction between the surfaces of different topologies:

- X a sphere, a compact Riemann surface of genus zero with K > 0;

- X a flat torus, or an elliptic curve, a Riemann surface of genus one with K = 0;

- and X a hyperbolic surface, which has genus greater than one and K < 0.

While in the first two cases the surface X admits infinitely many conformal automorphisms (in fact, the conformal automorphism group is a complex Lie group of dimension three for a sphere and of dimension one for a torus), a hyperbolic Riemann surface only admits a discrete set of automorphisms. Hurwitz's theorem claims that in fact more is true: it provides a uniform bound on the order of the automorphism group as a function of the genus and characterizes those Riemann surfaces for which the bound is sharp.

Statement and proof

Theorem: Let be a smooth connected Riemann surface of genus . Then its automorphism group has size at most .

Proof: Assume for now that is finite (this will be proved at the end).

- Consider the quotient map . Since acts by holomorphic functions, the quotient is locally of the form and the quotient is a smooth Riemann surface. The quotient map is a branched cover, and we will see below that the ramification points correspond to the orbits that have a non-trivial stabiliser. Let be the genus of .

- By the Riemann-Hurwitz formula, where the sum is over the ramification points for the quotient map . The ramification index at is just the order of the stabiliser group, since where the number of pre-images of (the number of points in the orbit), and . By definition of ramification points, for all ramification indices.

Now call the righthand side and since we must have . Rearranging the equation we find:

- If then , and

- If , then and so that ,

- If , then and

- if then , so that

- if then , so that ,

- if then write . We may assume .

- if then so that ,

- if then

- if then so that ,

- if then so that .

In conclusion, .

To show that is finite, note that acts on the cohomology preserving the Hodge decomposition and the lattice .

- In particular, its action on gives a homomorphism with discrete image .

- In addition, the image preserves the natural non-degenerate Hermitian inner product on . In particular the image is contained in the unitary group which is compact. Thus the image is not just discrete, but finite.

- It remains to prove that has finite kernel. In fact, we will prove is injective. Assume acts as the identity on . If is finite, then by the Lefschetz fixed-point theorem,

This is a contradiction, and so is infinite. Since is a closed complex sub variety of positive dimension and is a smooth connected curve (i.e. ), we must have . Thus is the identity, and we conclude that is injective and is finite. Q.E.D.

Corollary of the proof: A Riemann surface of genus has automorphisms if and only if is a branched cover with three ramification points, of indices 2,3 and 7.

The idea of another proof and construction of the Hurwitz surfaces

By the uniformization theorem, any hyperbolic surface X – i.e., the Gaussian curvature of X is equal to negative one at every point – is covered by the hyperbolic plane. The conformal mappings of the surface correspond to orientation-preserving automorphisms of the hyperbolic plane. By the Gauss–Bonnet theorem, the area of the surface is

- A(X) = − 2π χ(X) = 4π(g − 1).

In order to make the automorphism group G of X as large as possible, we want the area of its fundamental domain D for this action to be as small as possible. If the fundamental domain is a triangle with the vertex angles π/p, π/q and π/r, defining a tiling of the hyperbolic plane, then p, q, and r are integers greater than one, and the area is

- A(D) = π(1 − 1/p − 1/q − 1/r).

Thus we are asking for integers which make the expression

- 1 − 1/p − 1/q − 1/r

strictly positive and as small as possible. This minimal value is 1/42, and

- 1 − 1/2 − 1/3 − 1/7 = 1/42

gives a unique triple of such integers. This would indicate that the order |G| of the automorphism group is bounded by

- A(X)/A(D) ≤ 168(g − 1).

However, a more delicate reasoning shows that this is an overestimate by the factor of two, because the group G can contain orientation-reversing transformations. For the orientation-preserving conformal automorphisms the bound is 84(g − 1).

Construction

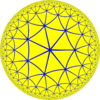

To obtain an example of a Hurwitz group, let us start with a (2,3,7)-tiling of the hyperbolic plane. Its full symmetry group is the full (2,3,7) triangle group generated by the reflections across the sides of a single fundamental triangle with the angles π/2, π/3 and π/7. Since a reflection flips the triangle and changes the orientation, we can join the triangles in pairs and obtain an orientation-preserving tiling polygon. A Hurwitz surface is obtained by 'closing up' a part of this infinite tiling of the hyperbolic plane to a compact Riemann surface of genus g. This will necessarily involve exactly 84(g − 1) double triangle tiles.

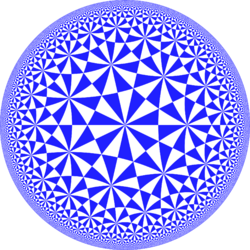

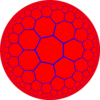

The following two regular tilings have the desired symmetry group; the rotational group corresponds to rotation about an edge, a vertex, and a face, while the full symmetry group would also include a reflection. The polygons in the tiling are not fundamental domains – the tiling by (2,3,7) triangles refines both of these and is not regular.

order-3 heptagonal tiling |

order-7 triangular tiling |

Wythoff constructions yields further uniform tilings, yielding eight uniform tilings, including the two regular ones given here. These all descend to Hurwitz surfaces, yielding tilings of the surfaces (triangulation, tiling by heptagons, etc.).

From the arguments above it can be inferred that a Hurwitz group G is characterized by the property that it is a finite quotient of the group with two generators a and b and three relations

thus G is a finite group generated by two elements of orders two and three, whose product is of order seven. More precisely, any Hurwitz surface, that is, a hyperbolic surface that realizes the maximum order of the automorphism group for the surfaces of a given genus, can be obtained by the construction given. This is the last part of the theorem of Hurwitz.

Examples of Hurwitz groups and surfaces

The smallest Hurwitz group is the projective special linear group PSL(2,7), of order 168, and the corresponding curve is the Klein quartic curve. This group is also isomorphic to PSL(3,2).

Next is the Macbeath curve, with automorphism group PSL(2,8) of order 504. Many more finite simple groups are Hurwitz groups; for instance all but 64 of the alternating groups are Hurwitz groups, the largest non-Hurwitz example being of degree 167. The smallest alternating group that is a Hurwitz group is A15.

Most projective special linear groups of large rank are Hurwitz groups, (Lucchini Tamburini). For lower ranks, fewer such groups are Hurwitz. For np the order of p modulo 7, one has that PSL(2,q) is Hurwitz if and only if either q=7 or q = pnp. Indeed, PSL(3,q) is Hurwitz if and only if q = 2, PSL(4,q) is never Hurwitz, and PSL(5,q) is Hurwitz if and only if q = 74 or q = pnp, (Tamburini Vsemirnov).

Similarly, many groups of Lie type are Hurwitz. The finite classical groups of large rank are Hurwitz, (Lucchini Tamburini). The exceptional Lie groups of type G2 and the Ree groups of type 2G2 are nearly always Hurwitz, (Malle 1990). Other families of exceptional and twisted Lie groups of low rank are shown to be Hurwitz in (Malle 1995).

There are 12 sporadic groups that can be generated as Hurwitz groups: the Janko groups J1, J2 and J4, the Fischer groups Fi22 and Fi'24, the Rudvalis group, the Held group, the Thompson group, the Harada–Norton group, the third Conway group Co3, the Lyons group, and the Monster, (Wilson 2001).

Automorphism groups in low genus

The largest |Aut(X)| can get for a Riemann surface X of genus g is shown below, for 2≤g≤10, along with a surface X0 with |Aut(X0)| maximal.

| genus g | Largest possible |Aut(X)| | X0 | Aut(X0) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 48 | Bolza curve | GL2(3) |

| 3 | 168 (Hurwitz bound) | Klein quartic | PSL2(7) |

| 4 | 120 | Bring curve | S5 |

| 5 | 192 | Modular curve X(8) | PSL2(Z/8Z) |

| 6 | 150 | Fermat curve F5 | (C5 x C5):S3 |

| 7 | 504 (Hurwitz bound) | Macbeath curve | PSL2(8) |

| 8 | 336 | ||

| 9 | 320 | ||

| 10 | 432 | ||

| 11 | 240 |

In this range, there only exists a Hurwitz curve in genus g=3 and g=7.

Generalizations

The concept of a Hurwitz surface can be generalized in several ways to a definition that has examples in all but a few genera. Perhaps the most natural is a "maximally symmetric" surface: One that cannot be continuously modified through equally symmetric surfaces to a surface whose symmetry properly contains that of the original surface. This is possible for all orientable compact genera (see above section "Automorphism groups in low genus").

See also

Notes

- ↑ Technically speaking, there is an equivalence of categories between the category of compact Riemann surfaces with the orientation-preserving conformal maps and the category of non-singular complex projective algebraic curves with the algebraic morphisms.

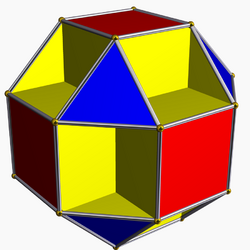

- ↑ (Richter {{{2}}}) Note each face in the polyhedron consist of multiple faces in the tiling – two triangular faces constitute a square face and so forth, as per this explanatory image.

References

- Hurwitz, A. (1893), "Über algebraische Gebilde mit Eindeutigen Transformationen in sich", Mathematische Annalen 41 (3): 403–442, doi:10.1007/BF01443420.

- Lucchini, A.; Tamburini, M. C. (1999), "Classical groups of large rank as Hurwitz groups", Journal of Algebra 219 (2): 531–546, doi:10.1006/jabr.1999.7911, ISSN 0021-8693

- Lucchini, A.; Tamburini, M. C.; Wilson, J. S. (2000), "Hurwitz groups of large rank", Journal of the London Mathematical Society, Second Series 61 (1): 81–92, doi:10.1112/S0024610799008467, ISSN 0024-6107

- Malle, Gunter (1990), "Hurwitz groups and G2(q)", Canadian Mathematical Bulletin 33 (3): 349–357, doi:10.4153/CMB-1990-059-8, ISSN 0008-4395

- Malle, Gunter (1995), "Small rank exceptional Hurwitz groups", Groups of Lie type and their geometries (Como, 1993), London Math. Soc. Lecture Note Ser., 207, Cambridge University Press, pp. 173–183

- Tamburini, M. C.; Vsemirnov, M. (2006), "Irreducible (2,3,7)-subgroups of PGL(n,F) for n ≤ 7", Journal of Algebra 300 (1): 339–362, doi:10.1016/j.jalgebra.2006.02.030, ISSN 0021-8693

- Wilson, R. A. (2001), "The Monster is a Hurwitz group", Journal of Group Theory 4 (4): 367–374, doi:10.1515/jgth.2001.027, http://web.mat.bham.ac.uk/R.A.Wilson/pubs/MHurwitz.ps, retrieved 2015-09-04

- Richter, David A., How to Make the Mathieu Group M24, http://homepages.wmich.edu/~drichter/mathieu.htm, retrieved 2010-04-15

|