Bézout's theorem

Bézout's theorem is a statement in algebraic geometry concerning the number of common zeros of n polynomials in n indeterminates. In its original form the theorem states that in general the number of common zeros equals the product of the degrees of the polynomials.[1] It is named after Étienne Bézout.

In some elementary texts, Bézout's theorem refers only to the case of two variables, and asserts that, if two plane algebraic curves of degrees and have no component in common, they have intersection points, counted with their multiplicity, and including points at infinity and points with complex coordinates.[2]

In its modern formulation, the theorem states that, if N is the number of common points over an algebraically closed field of n projective hypersurfaces defined by homogeneous polynomials in n + 1 indeterminates, then N is either infinite, or equals the product of the degrees of the polynomials. Moreover, the finite case occurs almost always.

In the case of two variables and in the case of affine hypersurfaces, if multiplicities and points at infinity are not counted, this theorem provides only an upper bound of the number of points, which is almost always reached. This bound is often referred to as the Bézout bound.

Bézout's theorem is fundamental in computer algebra and effective algebraic geometry, by showing that most problems have a computational complexity that is at least exponential in the number of variables. It follows that in these areas, the best complexity that can be hoped for will occur with algorithms that have a complexity that is polynomial in the Bézout bound.

History

In the case of plane curves, Bézout's theorem was essentially stated by Isaac Newton in his proof of Lemma 28 of volume 1 of his Principia in 1687, where he claims that two curves have a number of intersection points given by the product of their degrees.[3]

The general theorem was later published in 1779 in Étienne Bézout's Théorie générale des équations algébriques. He supposed the equations to be "complete", which in modern terminology would translate to generic. Since with generic polynomials, there are no points at infinity, and all multiplicities equal one, Bézout's formulation is correct, although his proof does not follow the modern requirements of rigor. This and the fact that the concept of intersection multiplicity was outside the knowledge of his time led to a sentiment expressed by some authors that his proof was neither correct nor the first proof to be given.[4]

The proof of the statement that includes multiplicities requires an accurate definition of the intersection multiplicities, and was therefore not possible before the 20th century. The definitions of multiplicities that was given during the first half of the 20th century involved continuous and infinitesimal deformations. It follows that the proofs of this period apply only over the field of complex numbers. It is only in 1958 that Jean-Pierre Serre gave a purely algebraic definition of multiplicities, which led to a proof valid over any algebraically closed field.[5]

Modern studies related to Bézout's theorem obtained different upper bounds to system of polynomials by using other properties of the polynomials, such as the Bernstein–Kushnirenko theorem, or generalized it to a large class of functions, such as Nash functions.[6]

Statement

Plane curves

Suppose that X and Y are two plane projective curves defined over a field F that do not have a common component (this condition means that X and Y are defined by polynomials, without common divisor of positive degree). Then the total number of intersection points of X and Y with coordinates in an algebraically closed field E that contains F, counted with their multiplicities, is equal to the product of the degrees of X and Y.

General case

The generalization in higher dimension may be stated as:

Let n projective hypersurfaces be given in a projective space of dimension n over an algebraically closed field, which are defined by n homogeneous polynomials in n + 1 variables, of degrees Then either the number of intersection points is infinite, or the number of intersection points, counted with multiplicity, is equal to the product If the hypersurfaces are in relative general position, then there are intersection points, all with multiplicity 1.

There are various proofs of this theorem, which either are expressed in purely algebraic terms, or use the language or algebraic geometry. Three algebraic proofs are sketched below.

Bézout's theorem has been generalized as the so-called multi-homogeneous Bézout theorem.

Affine case

The affine case of the theorem is the following statement, that was proven in 1983 by David Masser and Gisbert Wüstholz.[7]

Consider n affine hypersurfaces that are defined over an algebraically closed field by n polynomials in n variables, of degrees Then either the number of intersection points is infinite, or the number of intersection points, counted with their multiplicities, is at most the product If the hypersurfaces are in relative general position, then there are exactly intersection points, all with multiplicity 1.

This version is not a direct consequence of the general case, because it is possible to have a finite number of intersection points in the affine space, with infinitely many intersection points at infinity. The above statement is a special case of a more general statement, which is the result that Masser and Wüstholz proved.

For stating the general result, one has to recall that the intersection points form an algebraic set, and that there is a finite number of intersection points if and only if all component of the intersection have a zero dimension (an algebraic set of positive dimension has an infinity of points over an algebraically closed field). An intersection point is said isolated if it does not belong to a component of positive dimension of the intersection; the terminology make sense, since an isolated intersection point has neighborhoods (for Zariski topology or for the usual topology in the case of complex hypersurfaces) that does not contain any other intersection point.

Consider n projective hypersurfaces that are defined over an algebraically closed field by n homogeneous polynomials in variables, of degrees Then, the sum of the multiplicities of their isolated intersection points is at most the product The result remains valid for any number m of hypersurfaces, if one sets in the case and, otherwise, if one orders the degrees for having That is, there is no isolated intersection point if and, otherwise, the bound is the product of the smallest degree and the largest degrees.

Examples (plane curves)

Two lines

The equation of a line in a Euclidean plane is linear, that is, it equates to zero a polynomial of degree one. So, the Bézout bound for two lines is 1, meaning that two lines either intersect at a single point, or do not intersect. In the latter case, the lines are parallel and meet at a point at infinity.

One can verify this with equations. The equation of a first line can be written in slope-intercept form or, in projective coordinates (if the line is vertical, one may exchange x and y). If the equation of a second line is (in projective coordinates) by substituting for y in it, one gets If one gets the x-coordinate of the intersection point by solving the latter equation in x and putting t = 1.

If that is the two line are parallel as having the same slope. If they are distinct, and the substituted equation gives t = 0. This gives the point at infinity of projective coordinates (1, s, 0).

A line and a curve

As above, one may write the equation of the line in projective coordinates as If curve is defined in projective coordinates by a homogeneous polynomial of degree n, the substitution of y provides a homogeneous polynomial of degree n in x and t. The fundamental theorem of algebra implies that it can be factored in linear factors. Each factor gives the ratio of the x and t coordinates of an intersection point, and the multiplicity of the factor is the multiplicity of the intersection point.

If t is viewed as the coordinate of infinity, a factor equal to t represents an intersection point at infinity.

If at least one partial derivative of the polynomial p is not zero at an intersection point, then the tangent of the curve at this point is defined (see Algebraic curve § Tangent at a point), and the intersection multiplicity is greater than one if and only if the line is tangent to the curve. If all partial derivatives are zero, the intersection point is a singular point, and the intersection multiplicity is at least two.

Two conic sections

Two conic sections generally intersect in four points, some of which may coincide. To properly account for all intersection points, it may be necessary to allow complex coordinates and include the points on the infinite line in the projective plane. For example:

- Two circles never intersect in more than two points in the plane, while Bézout's theorem predicts four. The discrepancy comes from the fact that every circle passes through the same two complex points on the line at infinity. Writing the circle in homogeneous coordinates, we get from which it is clear that the two points (1 : i : 0) and (1 : –i : 0) lie on every circle. When two circles do not meet at all in the real plane, the two other intersections have non-real coordinates, or if the circles are concentric then they meet at exactly the two points on the line at infinity with an intersection multiplicity of two.

- Any conic should meet the line at infinity at two points according to the theorem. A hyperbola meets it at two real points corresponding to the two directions of the asymptotes. An ellipse meets it at two complex points, which are conjugate to one another—in the case of a circle, the points (1 : i : 0) and (1 : –i : 0). A parabola meets it at only one point, but it is a point of tangency and therefore counts twice.

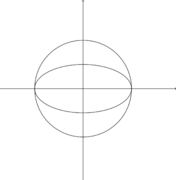

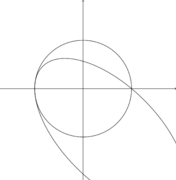

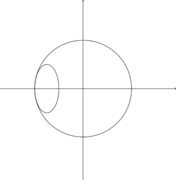

- The following pictures show examples in which the circle x2 + y2 – 1 = 0 meets another ellipse in fewer intersection points because at least one of them has multiplicity greater than one:

Multiplicity

The concept of multiplicity is fundamental for Bézout's theorem, as it allows having an equality instead of a much weaker inequality.

Intuitively, the multiplicity of a common zero of several polynomials is the number of zeros into which the common zero can split when the coefficients are slightly changed. For example, a tangent to a curve is a line that cuts the curve at a point that splits in several points if the line is slightly moved. This number is two in general (ordinary points), but may be higher (three for inflection points, four for undulation points, etc.). This number is the "multiplicity of contact" of the tangent.

This definition of a multiplicities by deformation was sufficient until the end of the 19th century, but has several problems that led to more convenient modern definitions: Deformations are difficult to manipulate; for example, in the case of a root of a univariate polynomial, for proving that the multiplicity obtained by deformation equals the multiplicity of the corresponding linear factor of the polynomial, one has to know that the roots are continuous functions of the coefficients. Deformations cannot be used over fields of positive characteristic. Moreover, there are cases where a convenient deformation is difficult to define (as in the case of more than two plane curves having a common intersection point), and even cases where no deformation is possible.[citation needed]

Currently, following Jean-Pierre Serre, a multiplicity is generally defined as the length of a local ring associated with the point where the multiplicity is considered.[5] Most specific definitions can be shown to be special case of Serre's definition.

In the case of Bézout's theorem, the general intersection theory can be avoided, as there are proofs (see below) that associate to each input data for the theorem a polynomial in the coefficients of the equations, which factorizes into linear factors, each corresponding to a single intersection point. So, the multiplicity of an intersection point is the multiplicity of the corresponding factor. The proof that this multiplicity equals the one that is obtained by deformation, results then from the fact that the intersection points and the factored polynomial depend continuously on the roots.

Proofs

Using the resultant (plane curves)

Let P and Q be two homogeneous polynomials in the indeterminates x, y, t of respective degrees p and q. Their zeros are the homogeneous coordinates of two projective curves. Thus the homogeneous coordinates of their intersection points are the common zeros of P and Q.

By collecting together the powers of one indeterminate, say y, one gets univariate polynomials whose coefficients are homogeneous polynomials in x and t.

For technical reasons, one must change of coordinates in order that the degrees in y of P and Q equal their total degrees (p and q), and each line passing through two intersection points does not pass through the point (0, 1, 0) (this means that no two point have the same Cartesian x-coordinate.

The resultant R(x ,t) of P and Q with respect to y is a homogeneous polynomial in x and t that has the following property: with if and only if it exist such that is a common zero of P and Q (see Resultant § Zeros). The above technical condition ensures that is unique. The first above technical condition means that the degrees used in the definition of the resultant are p and q; this implies that the degree of R is pq (see Resultant § Homogeneity).

As R is a homogeneous polynomial in two indeterminates, the fundamental theorem of algebra implies that R is a product of pq linear polynomials. If one defines the multiplicity of a common zero of P and Q as the number of occurrences of the corresponding factor in the product, Bézout's theorem is thus proved.

For proving that the intersection multiplicity that has just been defined equals the definition in terms of a deformation, it suffices to remark that the resultant and thus its linear factors are continuous functions of the coefficients of P and Q.

Proving the equality with other definitions of intersection multiplicities relies on the technicalities of these definitions and is therefore outside the scope of this article.

Using U-resultant

In the early 20th century, Francis Sowerby Macaulay introduced the multivariate resultant (also known as Macaulay's resultant) of n homogeneous polynomials in n indeterminates, which is generalization of the usual resultant of two polynomials. Macaulay's resultant is a polynomial function of the coefficients of n homogeneous polynomials that is zero if and only the polynomials have a nontrivial (that is some component is nonzero) common zero in an algebraically closed field containing the coefficients.

The U-resultant is a particular instance of Macaulay's resultant, introduced also by Macaulay. Given n homogeneous polynomials in n + 1 indeterminates the U-resultant is the resultant of and where the coefficients are auxiliary indeterminates. The U-resultant is a homogeneous polynomial in whose degree is the product of the degrees of the

Although a multivariate polynomial is generally irreducible, the U-resultant can be factorized into linear (in the ) polynomials over an algebraically closed field containing the coefficients of the These linear factors correspond to the common zeros of the in the following way: to each common zero corresponds a linear factor and conversely.

This proves Bézout's theorem, if the multiplicity of a common zero is defined as the multiplicity of the corresponding linear factor of the U-resultant. As for the preceding proof, the equality of this multiplicity with the definition by deformation results from the continuity of the U-resultant as a function of the coefficients of the

This proof of Bézout's theorem seems the oldest proof that satisfies the modern criteria of rigor.

Using the degree of an ideal

Bézout's theorem can be proved by recurrence on the number of polynomials by using the following theorem.

Let V be a projective algebraic set of dimension and degree , and H be a hypersurface (defined by a single polynomial) of degree , that does not contain any irreducible component of V; under these hypotheses, the intersection of V and H has dimension and degree

For a (sketched) proof using Hilbert series, see Hilbert series and Hilbert polynomial § Degree of a projective variety and Bézout's theorem.

Beside allowing a conceptually simple proof of Bézout's theorem, this theorem is fundamental for intersection theory, since this theory is essentially devoted to the study of intersection multiplicities when the hypotheses of the above theorem do not apply.

See also

- Multi-homogeneous Bézout theorem

- AF+BG theorem – About algebraic curves passing through all intersection points of two other curves

- Bernstein–Kushnirenko theorem – On the number of common zeros of Laurent polynomials

Notes

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Bézout's theorem", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Bezout.html.

- ↑ Fulton 1974.

- ↑ Newton 1966.

- ↑ Kirwan, Frances (1992). Complex Algebraic Curves. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42353-8.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Serre 1965.

- ↑ Ramanakoraisina, R. (1989). "Bezout theorem for nash functions" (in en). Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra 61 (3): 295–301. doi:10.1016/0022-4049(89)90080-7. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0022404989900807.

- ↑ Masser & Wüstholz 1983.

References

- Fulton, William (1974). Algebraic Curves. Mathematics Lecture Note Series. W.A. Benjamin. p. 112. ISBN:0-8053-3081-4.

- Masser, David; Wüstholz, Gisbert (1983). "Fields of large transcendence degree generated by values of elliptic functions". Inventiones Mathematicae (Springer) 72 (3): 407–464. doi:10.1007/BF01398396. Bibcode: 1983InMat..72..407M.

- Newton, I. (1966), Principia Vol. I The Motion of Bodies (based on Newton's 2nd edition (1713); translated by Andrew Motte (1729) and revised by Florian Cajori (1934) ed.), Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-00928-8 Alternative translation of earlier (2nd) edition of Newton's Principia.

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1965). Algèbre locale et multiplicités: cours au Collège de France, 1957–1958, rédigé par Pierre Gabriel. Springer.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Bezout theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/b016000

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Bézout's Theorem". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/BezoutsTheorem.html.

- Bezout's Theorem at MathPages

|