Dessin d'enfant

In mathematics, a dessin d'enfant is a type of graph embedding used to study Riemann surfaces and to provide combinatorial invariants for the action of the absolute Galois group of the rational numbers. The name of these embeddings is French for a "child's drawing"; its plural is either dessins d'enfant, "child's drawings", or dessins d'enfants, "children's drawings".

A dessin d'enfant is a graph, with its vertices colored alternately black and white, embedded in an oriented surface that, in many cases, is simply a plane. For the coloring to exist, the graph must be bipartite. The faces of the embedding are required be topological disks. The surface and the embedding may be described combinatorially using a rotation system, a cyclic order of the edges surrounding each vertex of the graph that describes the order in which the edges would be crossed by a path that travels clockwise on the surface in a small loop around the vertex.

Any dessin can provide the surface it is embedded in with a structure as a Riemann surface. It is natural to ask which Riemann surfaces arise in this way. The answer is provided by Belyi's theorem, which states that the Riemann surfaces that can be described by dessins are precisely those that can be defined as algebraic curves over the field of algebraic numbers. The absolute Galois group transforms these particular curves into each other, and thereby also transforms the underlying dessins.

For a more detailed treatment of this subject, see (Schneps 1994) or (Lando Zvonkin).

History

19th century

Early proto-forms of dessins d'enfants appeared as early as 1856 in the icosian calculus of William Rowan Hamilton;[1] in modern terms, these are Hamiltonian paths on the icosahedral graph.

Recognizable modern dessins d'enfants and Belyi functions were used by Felix Klein.[2] Klein called these diagrams Linienzüge (German, plural of Linienzug "line-track", also used as a term for polygon); he used a white circle for the preimage of 0 and a '+' for the preimage of 1, rather than a black circle for 0 and white circle for 1 as in modern notation.[3] He used these diagrams to construct an 11-fold cover of the Riemann sphere by itself, with monodromy group , following earlier constructions of a 7-fold cover with monodromy connected to the Klein quartic.[4] These were all related to his investigations of the geometry of the quintic equation and the group , collected in his famous 1884/88 Lectures on the Icosahedron. The three surfaces constructed in this way from these three groups were much later shown to be closely related through the phenomenon of trinity.

20th century

Dessins d'enfant in their modern form were then rediscovered over a century later and named by Alexander Grothendieck in 1984 in his Esquisse d'un Programme.[5] (Zapponi 2003) quotes Grothendieck regarding his discovery of the Galois action on dessins d'enfants:

| “ | This discovery, which is technically so simple, made a very strong impression on me, and it represents a decisive turning point in the course of my reflections, a shift in particular of my centre of interest in mathematics, which suddenly found itself strongly focused. I do not believe that a mathematical fact has ever struck me quite so strongly as this one, nor had a comparable psychological impact. This is surely because of the very familiar, non-technical nature of the objects considered, of which any child’s drawing scrawled on a bit of paper (at least if the drawing is made without lifting the pencil) gives a perfectly explicit example. To such a dessin we find associated subtle arithmetic invariants, which are completely turned topsy-turvy as soon as we add one more stroke. | ” |

Part of the theory had already been developed independently by (Jones Singerman) some time before Grothendieck. They outline the correspondence between maps on topological surfaces, maps on Riemann surfaces, and groups with certain distinguished generators, but do not consider the Galois action. Their notion of a map corresponds to a particular instance of a dessin d'enfant. Later work by (Bryant Singerman) extends the treatment to surfaces with a boundary.

Riemann surfaces and Belyi pairs

The complex numbers, together with a special point designated as , form a topological space known as the Riemann sphere. Any polynomial, and more generally any rational function where and are polynomials, transforms the Riemann sphere by mapping it to itself. Consider, for example,[6] the rational function

At most points of the Riemann sphere, this transformation is a local homeomorphism: it maps a small disk centered at any point in a one-to-one way into another disk. However, at certain critical points, the mapping is more complicated, and maps a disk centered at the point in a -to-one way onto its image. The number is known as the degree of the critical point and the transformed image of a critical point is known as a critical value. The example given above, , has the following critical points and critical values. (Some points of the Riemann sphere that, while not themselves critical, map to one of the critical values, are also included; these are indicated by having degree one.)

| critical point x | critical value f(x) | degree |

|---|---|---|

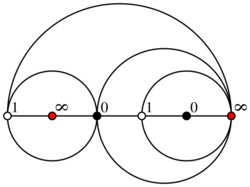

One may form a dessin d'enfant from by placing black points at the preimages of 0 (that is, at 1 and 9), white points at the preimages of 1 (that is, at ), and arcs at the preimages of the line segment [0, 1]. This line segment has four preimages, two along the line segment from 1 to 9 and two forming a simple closed curve that loops from 1 to itself, surrounding 0; the resulting dessin is shown in the figure.

In the other direction, from this dessin, described as a combinatorial object without specifying the locations of the critical points, one may form a compact Riemann surface, and a map from that surface to the Riemann sphere, equivalent to the map from which the dessin was originally constructed. To do so, place a point labeled within each region of the dessin (shown as the red points in the second figure), and triangulate each region by connecting this point to the black and white points forming the boundary of the region, connecting multiple times to the same black or white point if it appears multiple times on the boundary of the region. Each triangle in the triangulation has three vertices labeled 0 (for the black points), 1 (for the white points), or . For each triangle, substitute a half-plane, either the upper half-plane for a triangle that has 0, 1, and in counterclockwise order or the lower half-plane for a triangle that has them in clockwise order, and for every adjacent pair of triangles glue the corresponding half-planes together along the portion of their boundaries indicated by the vertex labels. The resulting Riemann surface can be mapped to the Riemann sphere by using the identity map within each half-plane. Thus, the dessin d'enfant formed from is sufficient to describe itself up to biholomorphism. However, this construction identifies the Riemann surface only as a manifold with complex structure; it does not construct an embedding of this manifold as an algebraic curve in the complex projective plane, although such an embedding always exists.

The same construction applies more generally when is any Riemann surface and is a Belyi function; that is, a holomorphic function from to the Riemann sphere having only 0, 1, and as critical values. A pair of this type is known as a Belyi pair. From any Belyi pair one can form a dessin d'enfant, drawn on the surface , that has its black points at the preimages of 0, its white points at the preimages of 1, and its edges placed along the preimages of the line segment . Conversely, any dessin d'enfant on any surface can be used to define gluing instructions for a collection of halfspaces that together form a Riemann surface homeomorphic to ; mapping each halfspace by the identity to the Riemann sphere produces a Belyi function on , and therefore leads to a Belyi pair . Any two Belyi pairs that lead to combinatorially equivalent dessins d'enfants are biholomorphic, and Belyi's theorem implies that, for any compact Riemann surface defined over the algebraic numbers, there are a Belyi function and a dessin d'enfant that provides a combinatorial description of both and .

Maps and hypermaps

A vertex in a dessin has a graph-theoretic degree, the number of incident edges, that equals its degree as a critical point of the Belyi function. In the example above, all white points have degree two; dessins with the property that each white point has two edges are known as clean, and their corresponding Belyi functions are called pure. When this happens, one can describe the dessin by a simpler embedded graph, one that has only the black points as its vertices and that has an edge for each white point with endpoints at the white point's two black neighbors. For instance, the dessin shown in the figure could be drawn more simply in this way as a pair of black points with an edge between them and a self-loop on one of the points. It is common to draw only the black points of a clean dessin and to leave the white points unmarked; one can recover the full dessin by adding a white point at the midpoint of each edge of the map.

Thus, any embedding of a graph in a surface in which each face is a disk (that is, a topological map) gives rise to a dessin by treating the graph vertices as black points of a dessin, and placing white points at the midpoint of each embedded graph edge. If a map corresponds to a Belyi function , its dual map (the dessin formed from the preimages of the line segment ) corresponds to the multiplicative inverse .[7]

A dessin that is not clean can be transformed into a clean dessin in the same surface, by recoloring all of its points as black and adding new white points on each of its edges. The corresponding transformation of Belyi pairs is to replace a Belyi function by the pure Belyi function . One may calculate the critical points of directly from this formula: , , and . Thus, is the preimage under of the midpoint of the line segment , and the edges of the dessin formed from subdivide the edges of the dessin formed from .

Under the interpretation of a clean dessin as a map, an arbitrary dessin is a hypermap: that is, a drawing of a hypergraph in which the black points represent vertices and the white points represent hyperedges.

Regular maps and triangle groups

The five Platonic solids – the regular tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron – viewed as two-dimensional surfaces, have the property that any flag (a triple of a vertex, edge, and face that all meet each other) can be taken to any other flag by a symmetry of the surface. More generally, a map embedded in a surface with the same property, that any flag can be transformed to any other flag by a symmetry, is called a regular map.

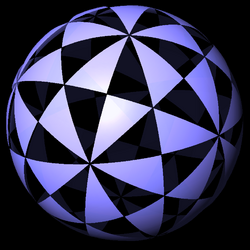

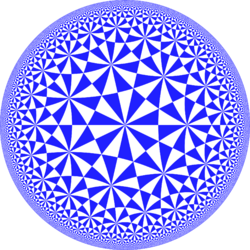

If a regular map is used to generate a clean dessin, and the resulting dessin is used to generate a triangulated Riemann surface, then the edges of the triangles lie along lines of symmetry of the surface, and the reflections across those lines generate a symmetry group called a triangle group, for which the triangles form the fundamental domains. For example, the figure shows the set of triangles generated in this way starting from a regular dodecahedron. When the regular map lies in a surface whose genus is greater than one, the universal cover of the surface is the hyperbolic plane, and the triangle group in the hyperbolic plane formed from the lifted triangulation is a (cocompact) Fuchsian group representing a discrete set of isometries of the hyperbolic plane. In this case, the starting surface is the quotient of the hyperbolic plane by a finite index subgroup Γ in this group.

Conversely, given a Riemann surface that is a quotient of a tiling (a tiling of the sphere, Euclidean plane, or hyperbolic plane by triangles with angles , , and , the associated dessin is the Cayley graph given by the order two and order three generators of the group, or equivalently, the tiling of the same surface by -gons meeting three per vertex. Vertices of this tiling give black dots of the dessin, centers of edges give white dots, and centers of faces give the points over infinity.

Trees and Shabat polynomials

The simplest bipartite graphs are the trees. Any embedding of a tree has a single region, and therefore by Euler's formula lies in a spherical surface. The corresponding Belyi pair forms a transformation of the Riemann sphere that, if one places the pole at , can be represented as a polynomial. Conversely, any polynomial with 0 and 1 as its finite critical values forms a Belyi function from the Riemann sphere to itself, having a single infinite-valued critical point, and corresponding to a dessin d'enfant that is a tree. The degree of the polynomial equals the number of edges in the corresponding tree. Such a polynomial Belyi function is known as a Shabat polynomial,[8] after George Shabat.

For example, take to be the monomial having only one finite critical point and critical value, both zero. Although 1 is not a critical value for , it is still possible to interpret as a Belyi function from the Riemann sphere to itself because its critical values all lie in the set . The corresponding dessin d'enfant is a star having one central black vertex connected to white leaves (a complete bipartite graph ).

More generally, a polynomial having two critical values and may be termed a Shabat polynomial. Such a polynomial may be normalized into a Belyi function, with its critical values at 0 and 1, by the formula but it may be more convenient to leave in its un-normalized form.[9]

An important family of examples of Shabat polynomials are given by the Chebyshev polynomials of the first kind, , which have −1 and 1 as critical values. The corresponding dessins take the form of path graphs, alternating between black and white vertices, with edges in the path. Due to the connection between Shabat polynomials and Chebyshev polynomials, Shabat polynomials themselves are sometimes called generalized Chebyshev polynomials.[9][10]

Different trees will, in general, correspond to different Shabat polynomials, as will different embeddings or colorings of the same tree. Up to normalization and linear transformations of its argument, the Shabat polynomial is uniquely determined from a coloring of an embedded tree, but it is not always straightforward to find a Shabat polynomial that has a given embedded tree as its dessin d'enfant.

The absolute Galois group and its invariants

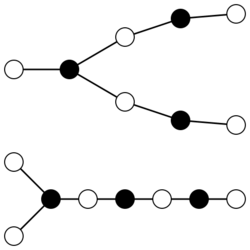

The polynomial may be made into a Shabat polynomial by choosing[11] The two choices of lead to two Belyi functions and . These functions, though closely related to each other, are not equivalent, as they are described by the two nonisomorphic trees shown in the figure.

However, as these polynomials are defined over the algebraic number field , they may be transformed by the action of the absolute Galois group of the rational numbers. An element of that transforms to will transform into and vice versa, and thus can also be said to transform each of the two trees shown in the figure into the other tree. More generally, due to the fact that the critical values of any Belyi function are the pure rationals 0, 1, and , these critical values are unchanged by the Galois action, so this action takes Belyi pairs to other Belyi pairs. One may define an action of on any dessin d'enfant by the corresponding action on Belyi pairs; this action, for instance, permutes the two trees shown in the figure.

Due to Belyi's theorem, the action of on dessins is faithful (that is, every two elements of define different permutations on the set of dessins),[12] so the study of dessins d'enfants can tell us much about itself. In this light, it is of great interest to understand which dessins may be transformed into each other by the action of and which may not. For instance, one may observe that the two trees shown have the same degree sequences for their black nodes and white nodes: both have a black node with degree three, two black nodes with degree two, two white nodes with degree two, and three white nodes with degree one. This equality is not a coincidence: whenever transforms one dessin into another, both will have the same degree sequence. The degree sequence is one known invariant of the Galois action, but not the only invariant.

The stabilizer of a dessin is the subgroup of consisting of group elements that leave the dessin unchanged. Due to the Galois correspondence between subgroups of and algebraic number fields, the stabilizer corresponds to a field, the field of moduli of the dessin. An orbit of a dessin is the set of all other dessins into which it may be transformed; due to the degree invariant, orbits are necessarily finite and stabilizers are of finite index. One may similarly define the stabilizer of an orbit (the subgroup that fixes all elements of the orbit) and the corresponding field of moduli of the orbit, another invariant of the dessin. The stabilizer of the orbit is the maximal normal subgroup of contained in the stabilizer of the dessin, and the field of moduli of the orbit corresponds to the smallest normal extension of that contains the field of moduli of the dessin. For instance, for the two conjugate dessins considered in this section, the field of moduli of the orbit is . The two Belyi functions and of this example are defined over the field of moduli, but there exist dessins for which the field of definition of the Belyi function must be larger than the field of moduli.[13]

Notes

- ↑ (Hamilton 1856). See also (Jones 1995).

- ↑ Klein (1879).

- ↑ le Bruyn (2008).

- ↑ (Klein 1878–1879a); (Klein 1878–1879b).

- ↑ (Grothendieck 1984)

- ↑ This example was suggested by (Lando Zvonkin), pp. 109–110.

- ↑ (Lando Zvonkin), pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Girondo & González-Diez (2012) p. 252

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 (Lando Zvonkin), p. 82.

- ↑ Jones, G. and Streit, M. "Galois groups, monodromy groups and cartographic groups", p. 43 in Schneps & Lochak (2007) pp. 25–66. Zbl 0898.14012

- ↑ (Lando Zvonkin), pp. 90–91. For the purposes of this example, ignore the parasitic solution .

- ↑ acts faithfully even when restricted to dessins that are trees; see (Lando Zvonkin), Theorem 2.4.15, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ (Lando Zvonkin), pp. 122–123.

References

- le Bruyn, Lieven (2008), Klein's dessins d'enfant and the buckyball, http://www.neverendingbooks.org/kleins-dessins-denfant-and-the-buckyball.

- Bryant, Robin P.; Singerman, David (1985), "Foundations of the theory of maps on surfaces with boundary", Quarterly Journal of Mathematics, Second Series 36 (141): 17–41, doi:10.1093/qmath/36.1.17.

- Girondo, Ernesto; González-Diez, Gabino (2012), Introduction to compact Riemann surfaces and dessins d'enfants, London Mathematical Society Student Texts, 79, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-74022-7.

- Grothendieck, A. (1984), Esquisse d'un programme

- Hamilton, W. R. (17 October 1856), Letter to John T. Graves "On the Icosian". Collected in Halberstam, H.; Ingram, R. E., eds. (1967), Mathematical papers, Vol. III, Algebra, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 612–625.

- Jones, Gareth (1995), "Dessins d'enfants: bipartite maps and Galois groups", Séminaire Lotharingien de Combinatoire B35d: 4, http://radon.mat.univie.ac.at/~slc/s/s35jones.html, retrieved 2 June 2010.

- Jones, Gareth; Singerman, David (1978), "Theory of maps on orientable surfaces", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 37 (2): 273–307, doi:10.1112/plms/s3-37.2.273.

- Klein, Felix (1878–79), "Über die Transformation der elliptischen Funktionen und die Auflösung der Gleichungen fünften Grades (On the transformation of elliptic functions and ...)", Mathematische Annalen 14: 13–75 (in Oeuvres, Tome 3), doi:10.1007/BF02297507, http://mathdoc.emath.fr/cgi-bin/oetoc?id=OE_KLEIN__3, retrieved 2 June 2010.

- Klein, Felix (1878–79), "Über die Transformation siebenter Ordnung der elliptischen Funktionen (On the seventh order transformation of elliptic functions)", Mathematische Annalen 14: 90–135 (in Oeuvres, Tome 3), doi:10.1007/BF01677143, http://mathdoc.emath.fr/cgi-bin/oetoc?doi=OE_KLEIN__3, retrieved 9 July 2010.

- Klein, Felix (1879), "Ueber die Transformation elfter Ordnung der elliptischen Functionen (On the eleventh order transformation of elliptic functions)", Mathematische Annalen 15 (3–4): 533–555, doi:10.1007/BF02086276, https://zenodo.org/record/1642598, collected as pp. 140–165 in Oeuvres, Tome 3 .

- Lando, Sergei K.; Zvonkin, Alexander K. (2004), Graphs on Surfaces and Their Applications, Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences: Lower-Dimensional Topology II, 141, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-00203-1. See especially chapter 2, "Dessins d'Enfants", pp. 79–153.

- Schneps, Leila, ed. (1994), The Grothendieck Theory of Dessins d'Enfants, London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-47821-2.

- Schneps, Leila; Lochak, Pierre, eds. (1997), Geometric Galois actions II. The inverse Galois problem, moduli spaces and mapping class groups. Proceedings of the conference on geometry and arithmetic of moduli spaces, Luminy, France, August 1995, London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, 243, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-59641-6.

- Shabat, G.B.; Voedvodsky, V.A. (2007), "Drawing curves over number fields", in Cartier, P.; Illusie, L.; Katz, N.M. et al., The Grothendieck Festschrift Volume III, Modern Birkhäuser Classics, Birkhäuser, pp. 199–227, ISBN 978-0-8176-4568-7.

- Singerman, David; Syddall, Robert I. (2003), "The Riemann Surface of a Uniform Dessin", Beiträge zur Algebra und Geometrie 44 (2): 413–430, http://www.emis.de/journals/BAG/vol.44/no.2/9.html.

- Zapponi, Leonardo (August 2003), "What is a Dessin d'Enfant", Notices of the American Mathematical Society 50 (7): 788–789, https://www.ams.org/notices/200307/what-is.pdf.

|