Link (knot theory)

In mathematical knot theory, a link is a collection of knots which do not intersect, but which may be linked (or knotted) together. A knot can be described as a link with one component. Links and knots are studied in a branch of mathematics called knot theory. Implicit in this definition is that there is a trivial reference link, usually called the unlink, but the word is also sometimes used in context where there is no notion of a trivial link.

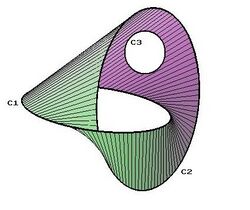

For example, a co-dimension 2 link in 3-dimensional space is a subspace of 3-dimensional Euclidean space (or often the 3-sphere) whose connected components are homeomorphic to circles.

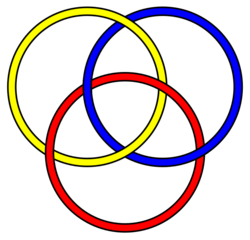

The simplest nontrivial example of a link with more than one component is called the Hopf link, which consists of two circles (or unknots) linked together once. The circles in the Borromean rings are collectively linked despite the fact that no two of them are directly linked. The Borromean rings thus form a Brunnian link and in fact constitute the simplest such link.

Generalizations

The notion of a link can be generalized in a number of ways.

General manifolds

Frequently the word link is used to describe any submanifold of the sphere diffeomorphic to a disjoint union of a finite number of spheres, .

In full generality, the word link is essentially the same as the word knot – the context is that one has a submanifold M of a manifold N (considered to be trivially embedded) and a non-trivial embedding of M in N, non-trivial in the sense that the 2nd embedding is not isotopic to the 1st. If M is disconnected, the embedding is called a link (or said to be linked). If M is connected, it is called a knot.

Tangles, string links, and braids

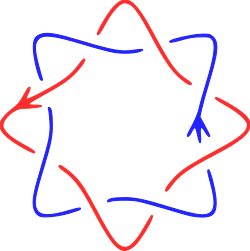

While (1-dimensional) links are defined as embeddings of circles, it is often interesting and especially technically useful to consider embedded intervals (strands), as in braid theory.

Most generally, one can consider a tangle[1][2] – a tangle is an embedding

of a (smooth) compact 1-manifold with boundary into the plane times the interval such that the boundary is embedded in

- ().

The type of a tangle is the manifold X, together with a fixed embedding of

Concretely, a connected compact 1-manifold with boundary is an interval or a circle (compactness rules out the open interval and the half-open interval neither of which yields non-trivial embeddings since the open end means that they can be shrunk to a point), so a possibly disconnected compact 1-manifold is a collection of n intervals and m circles The condition that the boundary of X lies in

says that intervals either connect two lines or connect two points on one of the lines, but imposes no conditions on the circles. One may view tangles as having a vertical direction (I), lying between and possibly connecting two lines

- ( and ),

and then being able to move in a two-dimensional horizontal direction ()

between these lines; one can project these to form a tangle diagram, analogous to a knot diagram.

Tangles include links (if X consists of circles only), braids, and others besides – for example, a strand connecting the two lines together with a circle linked around it.

In this context, a braid is defined as a tangle which is always going down – whose derivative always has a non-zero component in the vertical (I) direction. In particular, it must consist solely of intervals, and not double back on itself; however, no specification is made on where on the line the ends lie.

A string link is a tangle consisting of only intervals, with the ends of each strand required to lie at (0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 0), (1, 1), (2, 0), (2, 1), ... – i.e., connecting the integers, and ending in the same order that they began (one may use any other fixed set of points); if this has ℓ components, we call it an "ℓ-component string link". A string link need not be a braid – it may double back on itself, such as a two-component string link that features an overhand knot. A braid that is also a string link is called a pure braid, and corresponds with the usual such notion.

The key technical value of tangles and string links is that they have algebraic structure. Isotopy classes of tangles form a tensor category, where for the category structure, one can compose two tangles if the bottom end of one equals the top end of the other (so the boundaries can be stitched together), by stacking them – they do not literally form a category (pointwise) because there is no identity, since even a trivial tangle takes up vertical space, but up to isotopy they do. The tensor structure is given by juxtaposition of tangles – putting one tangle to the right of the other.

For a fixed ℓ, isotopy classes of ℓ-component string links form a monoid (one can compose all ℓ-component string links, and there is an identity), but not a group, as isotopy classes of string links need not have inverses. However, concordance classes (and thus also homotopy classes) of string links do have inverses, where inverse is given by flipping the string link upside down, and thus form a group.

Every link can be cut apart to form a string link, though this is not unique, and invariants of links can sometimes be understood as invariants of string links – this is the case for Milnor's invariants, for instance. Compare with closed braids.

See also

- Hyperbolic link

- Unlink

- Link group

References

- ↑ Habegger, Nathan; Lin, X.S. (1990), "The classification of links up to homotopy", Journal of the American Mathematical Society, 2 (American Mathematical Society) 3 (2): 389–419, doi:10.2307/1990959

- ↑ Habegger, Nathan; Masbaum, Gregor (2000), "The Kontsevich integral and Milnor's invariants", Topology 39 (6): 1253–1289, doi:10.1016/S0040-9383(99)00041-5

|