Medicine:Darier's disease

Darier's disease (DAR) is a rare, inherited skin disorder that presents with multiple greasy, crusting, thick brown bumps that merge into patches.[4] It is an autosomal dominant disorder discovered by French dermatologist Ferdinand-Jean Darier.

Mild forms of the disease are the most common, consisting solely of skin rashes that flare up under certain conditions such as high humidity, high stress, or tight-fitting clothes. Short stature, when combined with poorly-formed fingernails that contain vertical striations, is diagnostic even for mild forms of DAR. Symptoms will usually appear in late childhood or early adulthood between the ages of 15 and 30 years and will vary over the lifespan.

More severe cases are characterized by dark crusty patches on the skin that are mildly greasy and that emit a strong odor. These patches, also known as keratotic papules, keratosis follicularis, or dyskeratosis follicularis, most often appear on the scalp, forehead, upper arms, chest, back, knees, elbows, and behind the ear.[5][6]

Signs and symptoms

- Clinical symptoms of the disease:[citation needed]

- Seborrhoeic areas

- This is defined as areas where excess oil and sebum is released.

- Overall greasy or scaly skin either in the central chest and back or in the folds of the skin.

- Fragile or poorly formed fingernails

- Nail disease leading to V-shaped nicks at the edge of the nail.

- Rash that covers many areas of the body

- The rash is often associated with a strong unpleasant odor

- The rash can be aggravated by heat, humidity, and exposure to sunlight.

- Mucosal manifestation

- White cobblestone pattern of small papules

- Overgrowth of gums

- Usually affects the mouth, esophagus, rectum, vulva, vagina

- Oral symptoms can be diagnosed by a routine dental examination

- Seborrhoeic areas

- Other symptoms and their overall prevalence in the affected population:[7]

- In 80 to 90% of patients

- Acrokeratosis verruciformis[8]

- Acrokeratosis is characterized by several small wart-like and flat-topped bumps that line the skin on typically the hand and feet.[9]

- Hypermelanotic macule

- Patches on the skin that contain excess pigment, they often appear as dark patches in the skin.

- Pruritus

- Itching

- Subungual hyperkeratotic fragments

- Thickened skin that is often discolored, under nails, on either hands or feet.

- Palmar pits

- Usually red in color, they are pits or depressions in the palms or soles of the hands and feet.

- Acrokeratosis verruciformis[8]

- In 30 to 79% of patients

- Abnormal hair morphology

- Acne conglobata

- Typically described as cystic acne

- In 80 to 90% of patients

Genetics

Mutations in a single gene, ATP2A2, are responsible for the development of Darier's disease. ATP2A2 encodes the SERCA2 protein, which is a calcium pump localized to the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in nearly all cells and the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) in muscle cells. The ER is where protein processing and transport begins for proteins targeted for secretion. The SR is a specialized form of ER found in muscle cells that sequesters calcium, the regulated efflux of which into the cytosol stimulates muscle fiber contraction. Calcium acts as a second messenger in many cellular signal transduction pathways. SERCA2 is required for Ca2+ signaling in cells by removing nearly all Ca2+ ions from the cytoplasm and storing them in the ER/SR compartments.[10][11][12][13]

A large number of mutant alleles of ATP2A2 have been identified in association with Darier's Disease. One study of 19 families and 6 sporadic cases found 24 specific, novel mutations associated with DAR symptoms. This study reported a loose, imperfect correlation between the severity of ATP2A2 mutations with the severity of the condition. Significant variability in disease severity between members of the same family carrying the same mutation was also reported by this study, suggesting that genetic modifiers contribute to the phenotypic penetrance of certain mutations.[14]

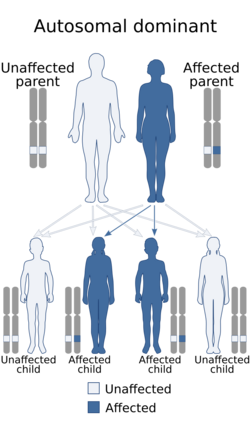

The mutation is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. This means that only one allele needs to be mutated in order to express the trait. This also means that someone who is born to one parent with DAR has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutant allele and having the disease. Loss-of-function mutations typically display recessive inheritance while the gain-of-function or hyperactive function of proteins is characteristic of dominant mutations. The observation that only one mutated allele of the SERCA2 is sufficient to produce clinical symptoms suggests that proper "gene dosage" is necessary for maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis in cells.[11] This means that two wild type copies of ATP2A2 are needed for proper cell function, which provides a logical basis for dominant phenotypes arising from loss-of-function alleles. Most ATP2A2 mutations are haploinsufficiency mutations, which means that only having only one functional copy of the functional gene results in a reduced level of protein expression that is not sufficient for wild type function for making enough of the coded protein for the cell to function properly. However, there is significant variability in disease severity in how the mutations are expressed even within families that have the same mutation. It is currently unclear in the current research why a reduction in SERCA2 expression/activity causes clinical symptoms restricted to the epidermis. One hypothesis that some researchers have given is that other cell types express additional "back-up" Ca2+ pumps that can compensate for the reduced function or expression of the SERCA2 protein, while skin cells rely exclusively on the SERCA2 gene for calcium sequestration, meaning only they are affected by its reduction in expression.[12]

As mentioned above, some cases of DAR result from somatic mutations to ATP2A2 in epidermal stem cells. These cases are referred to as instances of "linear" Darier's disease. Such individuals display phenotypic mosaicism, where the Darier's phenotype only affects the subset of epidermal tissue arising from the mutated progenitor cell. Somatic mutations are not inherited by the offspring of such individuals.[15]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Darier disease is often made by the appearance of the skin, family history, or genetic testing for the mutation in the ATP2A2 gene. However, many individuals are never diagnosed because of the mildness of their symptoms. Mild cases present clinically as minor rashes (without odor) that can become exacerbated by heat, humidity, stress, and sunlight. The symptoms of the disease are thought to be caused by an abnormality in the desmosome-keratin filament complex leading to a breakdown in cell adhesion.[12][8]

Darier's disease is an incommunicable disorder that is seen in males and females equally. Symptoms typically arise between the ages of 15 and 30. One study of 100 British individuals diagnosed with Darier's disease reported that affected individuals display elevated frequencies of neuropsychiatric conditions. There were high lifetime rates for mood disorders (50%), including depression (30%), bipolar disorder (4%), suicidal thoughts (31%), and suicide attempts (13%), suggesting a possible common genetic link.[16] Several case studies have suggested affected populations display elevated frequencies of learning disorders, but this has yet to be confirmed.[citation needed]

Treatment

Treatment of Darier disease depends on the severity of the presented clinical symptoms. In most minor cases, the disorder can be managed using sunscreen, moisturizing lotions, avoidance of non-breathable clothing, and excessive perspiration. In more severe cases of Darier's disease, hospitalisation may be required to heal affected individuals who display frequent relapse and remit patterns. In less severe cases, signs and symptoms may clear up completely through hygienic interventions. Most patients with Darier's disease live normal, healthy lives. Rapid resolution of rash symptoms can be complicated due to the increased vulnerability of affected skin surfaces by secondary bacterial or viral infections. Epidermal Staphylococcus aureus, human papillomavirus (HPV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections have been reported. In these cases, topical and/or oral antibiotic/antiviral medications may need to be prescribed.[17]

Typical recommendations are the application of antiseptics, soaking in astringents, antibiotics, benzoyl peroxide,[18] and topical diclofenac sodium.[19][20]

If Darier's is more localized, common treatments include:[citation needed]

- Topical retinoids: used to help in the reduction of hyperkeratosis, retinoids work by causing the skin cells in the top layers to die and be shed off. The common retinoids used for this disorder are:

- Dermabrasion

- Removal of the top layer of skin to help smooth and stimulate new growth of the skin.[21]

- Electrosurgery

- Used to help stop bleeding and remove abnormal skin growths.

- Topical corticosteroids

If symptoms are severe, oral retinoids are prescribed and have been proven to be 90% effective. However, there can be many adverse side-effects associated with prolonged use.[22] Common oral retinoids include acitretin, isotretinoin, and cyclosporine.

Some patients are able to prevent flares with use of topical sunscreens and oral vitamin C.[23]

Further information on and advocacy work for Darier's disease are provided by the FIRST Skin Foundation.[24]

Epidemiology

Worldwide prevalence is estimated as between 1:30,000 and 1:100,000. Case studies have shown estimated prevalence by country to be 3.8:100,000 in Slovenia,[25] 1:36,000 in north-east England,[26] 1:30,000 in Scotland,[27] and 1:100,000 in Denmark.[28]

History

Darier's disease was first described by the dermatologist Ferdinand-Jean Darier in the French dermatological journal Annales de dermatologie et de syphilographie.[29] Darier was a well-regarded dermatologist of the time who was the head of the medical department at the Hôpital Saint-Louis. Darier was an early proponent of histopathology, or the examination of samples of diseased flesh under a microscope to determine the cause of illnesses. Using this technique, he was able to uncover the origins of Darier's disease and a host of others that also bear his name.[30]

James Clarke White, a dermatologist at Harvard Medical School, independently characterized and published his observations on this dermatological disorder in the same year as Darier (1889), which is why the condition is also referred to as Darier-White disease.[31]

Court cases

In Singapore, there was a case of a man who escaped the death penalty for murder as a result of Darier's disease.

27-year-old Ong Teng Siew, a Malaysian and chicken slaughterer, was charged with murdering a 82-year-old opium addict Ng Gee Seh (alias Ng Ee Seng) in December 1995.[32][33] Ong was sentenced to death in August 1996 after the trial court found him guilty of murder,[34] and while he was in midst of appealing against his conviction and sentence, Ong was hospitalized in September 1996 for an outbreak of Darier's disease, which previously went undiagnosed before and during the trial, and after his lawyer Wong Siew Hong made a research and discovered that the disease had a causal link to various psychiatric disorders, the new evidence enabled Ong to successfully apply for a re-trial for Ng's murder.[35] After the trial court heard the new evidence, it accepted that at the time of the killing, Ong was suffering from diminished responsibility as a result of Darier's disease, and therefore, Ong was found guilty of a lesser offence of manslaughter and he was re-sentenced to life imprisonment in April 1998.[36][37]

See also

- Linear Darier disease

- List of cutaneous conditions

- Darier's sign

- Familial disseminated comedones without dyskeratosis

References

Notes

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis, MO: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN:0-07-138076-0.

- ↑ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN:0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "27. Genodermatoses and congenital anomalies" (in en). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Elsevier. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=UEaEDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA572.

- ↑ National Organization for Rare Disorders (2002). NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-3063-5.

- ↑ Sehgal, V. N.; Srivastava, G. (2005). "Darier's (Darier-White) disease/keratosis follicularis". International Journal of Dermatology 44 (3): 184–192. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02408.x. PMID 15807723.

- ↑ "Darier disease | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/6243/darier-disease.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Darier disease NZ". DermNet. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/darier-disease/.

- ↑ Acrokeratosis Verruciformis of Hopf: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology. 2020-03-26. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1055892-overview.

- ↑ Monk, Sarah; Sakuntabhai, Anavaj; Carter, Simon A.; Bryce, Steven D.; Cox, Roger; Harrington, Louise; Levy, Elaine; Ruiz-Perez, Victor L. et al. (April 1998). "Refined Genetic Mapping of the Darier Locus to a <1-cM Region of Chromosome 12q24.1, and Construction of a Complete, High-Resolution P1 Artificial Chromosome/Bacterial Artificial Chromosome Contig of the Critical Region". The American Journal of Human Genetics 62 (4): 890–903. doi:10.1086/301794. ISSN 0002-9297. PMID 9529352.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Foggia, Lucie; Hovnanian, Alain (2004). "Calcium pump disorders of the skin" (in fr). American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics 131C (1): 20–31. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30031. ISSN 1552-4876. PMID 15468148.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 Reference, Genetics Home. "Darier disease" (in en). https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/darier-disease.

- ↑ Sakuntabhai, Anavaj; Ruiz-Perez, Victor; Carter, Simon; Jacobsen, Nick; Burge, Susan; Monk, Sarah; Smith, Melanie; Munro, Colin S. et al. (March 1999). "Mutations in ATP2A2, encoding a Ca 2+ pump, cause Darier disease" (in en). Nature Genetics 21 (3): 271–277. doi:10.1038/6784. ISSN 1546-1718. PMID 10080178. https://www.nature.com/articles/ng0399_271.

- ↑ Ruiz-Perez, Victor L.; Carter, Simon A.; Healy, Eugene; Todd, Carole; Rees, Jonathan L.; Steijlen, Peter M.; Carmichael, Andrew J.; Lewis, Helen M. et al. (1999-09-01). "ATP2A2 Mutations in Darier's Disease: Variant Cutaneous Phenotypes Are Associated with Missense Mutations, But Neuropsychiatry Features Are Independent of Mutation Class" (in en). Human Molecular Genetics 8 (9): 1621–1630. doi:10.1093/hmg/8.9.1621. ISSN 0964-6906. PMID 10441324. https://academic.oup.com/hmg/article/8/9/1621/814081.

- ↑ Sakuntabhai, Anavaj; Dhitavat, Jittima; Hovnanian, Alain; Burge, Susan (December 2000). "Mosaicism for ATP2A2 Mutations Causes Segmental Darier's Disease". Journal of Investigative Dermatology 115 (6): 1144–1147. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00182.x. ISSN 0022-202X. PMID 11121153.

- ↑ "The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease". Br. J. Dermatol. 163 (3): 515–22. September 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x. PMID 20456342.

- ↑ Hohl, D. Hand, J. Darier disease. (2017) Corona, R. (Ed) Uptodate.

- ↑ Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews: Biochemistry (Champe, Harvey & Ferrier, ISBN:0-7817-2265-9, 3rd ed., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2005)

- ↑ "Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition restores ultraviolet B-induced downregulation of ATP2A2/SERCA2 in keratinocytes: possible therapeutic approach of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition for treatment of Darier disease". Br. J. Dermatol. 166 (5): 1017–22. May 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10789.x. PMID 22413864.

- ↑ "Improvement of Darier disease with diclofenac sodium 3% gel". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 70 (4): e89–e90. April 2014. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.033. PMID 24629373.

- ↑ "Dermabrasion: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia" (in en). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002987.htm.

- ↑ "How do retinol creams work, anyway?" (in en). 30 November 2018. https://getsundaily.com/blogs/skin-from-within/how-do-retinoid-creams-work-anyway.

- ↑ Andrew's Diseases of the Skin (James, Berger, Elston, 10th ed., Saunders Elsevier, 2006)

- ↑ "FIRST Skin Foundation". http://www.firstskinfoundation.org/darier-disease.

- ↑ "Epidemiology of Darier's Disease in Slovenia". Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 14 (2): 43–8. June 2005. PMID 16001099.

- ↑ "The phenotype of Darier's disease: penetrance and expressivity in adults and children". Br. J. Dermatol. 127 (2): 126–30. August 1992. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb08044.x. PMID 1390140.

- ↑ "Genetic epidemiology of Darier's disease: a population study in the west of Scotland". Br. J. Dermatol. 146 (1): 107–9. January 2002. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04559.x. PMID 11841374.

- ↑ "Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 27 (1): 40–50. July 1992. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70154-8. PMID 1619075.

- ↑ Crissey, John Thorne; Parish, Lawrence C.; Holubar, Karl (2013). "Late nineteenth century French dermatology" (in en). Historical Atlas of Dermatology and Dermatologists. CRC Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-84184-864-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=7ThZDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA75.

- ↑ Cadogan, Dr Mike (2019-03-01). "Ferdinand-Jean Darier • LITFL" (in en-US). https://litfl.com/ferdinand-jean-darier/.

- ↑ "Keratosis Follicularis (Darier Disease): Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". 2020-10-01. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1107340-overview.

- ↑ "Was he murdered?". The New Paper. 29 December 1995. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/newpaper19951229-1.2.11.1.

- ↑ "Chicken slaughterer charged with murder". The Straits Times. 4 January 1996. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19960104-1.2.39.9.

- ↑ "Man gets death for murdering opium addict, 82". The Straits Times. 13 August 1996. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19960813-1.2.29.15.

- ↑ "Did man's skin disease lead him to kill addict?". The Straits Times. 24 February 1998. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19980224-1.2.41.6.

- ↑ "Skin disease may save man's life". The Straits Times. 18 April 1998. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19980418-1.2.4.

- ↑ "Skin disease saves man's neck". The Straits Times. 28 May 1998. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19980528-1.2.42.12.

Sources

- Cardoso, Camila Lopes; Freitas, Patrícia; Taveira, Luís Antônio de Assis; Consolaro, Alberto (2006). "Darier disease: case report with oral manifestations". Medicina Oral Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal 11 (E404-6). https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/medicorpa/v11n5/04.pdf.

|