Medicine:Meckel syndrome

| Meckel syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

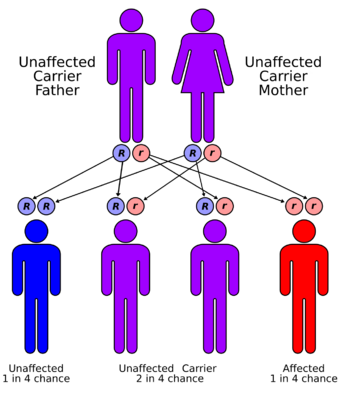

| This condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, meaning two copies of the gene in each cell are altered |

Meckel syndrome (also known as Meckel–Gruber syndrome, Gruber syndrome, dysencephalia splanchnocystica) is a rare, lethal, ciliopathic, genetic disorder, characterized by renal cystic dysplasia, central nervous system malformations (occipital encephalocele), polydactyly (post axial), hepatic developmental defects, and pulmonary hypoplasia due to oligohydramnios.

Meckel–Gruber syndrome is named for Johann Meckel and Georg Gruber.[1][2][3]

Pathophysiology

Meckel–Gruber syndrome (MKS) is an autosomal recessive lethal malformation. Recently, two MKS genes, MKS1 and MKS3, have been identified. A study done recently has described the cellular, sub-cellular and functional characterization of the novel proteins, MKS1 and meckelin, encoded by these genes.[4] The malfunction of this protein production is mainly responsible for this lethal disorder.

| Type | OMIM | Gene |

|---|---|---|

| MKS1 | 609883 | MKS1 |

| MKS2 | 603194 | TMEM216 |

| MKS3 | 607361 | TMEM67 |

| MKS4 | 611134 | CEP290 |

| MKS5 | 611561 | RPGRIP1L |

| MKS6 | 612284 | CC2D2A |

| MKS7 | 608002 | NPHP3 |

| MKS8 | 613846 | TCTN2 |

| MKS9 | 614144 | B9D1 |

| MKS10 | 611951 | B9D2 |

Relation to other rare genetic disorders

Recent findings in genetic research have suggested that a large number of genetic disorders, both genetic syndromes and genetic diseases, that were not previously identified in the medical literature as related, may be, in fact, highly related in the genetypical root cause of the widely varying, phenotypically-observed disorders. Thus, Meckel–Gruber syndrome is a ciliopathy. Other known ciliopathies include primary ciliary dyskinesia, Bardet–Biedl syndrome, polycystic kidney and liver disease, nephronophthisis, Alström syndrome, and some forms of retinal degeneration.[5] The MKS1 gene has been identified as being associated with a ciliopathy.[6]

Diagnosis

Dysplastic kidneys are prevalent in over 95% of all identified cases. When this occurs, microscopic cysts develop within the kidney and slowly destroy it, causing it to enlarge to 10 to 20 times its original size. The level of amniotic fluid within the womb may be significantly altered or remain normal, and a normal level of fluid should not be criteria for exclusion of diagnosis.[citation needed]

Occipital encephalocele is present in 60% to 80% of all cases, and post-axial polydactyly is present in 55% to 75% of the total number of identified cases. Bowing or shortening of the limbs are also common.[citation needed]

Finding at least two of the three phenotypic features of the classical triad, in the presence of normal karyotype, makes the diagnosis solid. Regular ultrasounds and pro-active prenatal care can usually detect symptoms early on in a pregnancy.[citation needed]

Management

Incidence

While not precisely known, it is estimated that the general rate of incidence, according to Bergsma,[7] for Meckel syndrome is 0.02 per 10,000 births. According to another study done six years later, the incidence rate could vary from 0.07 to 0.7 per 10,000 births.[8]

This syndrome is a Finnish heritage disease. Its frequency is much higher in Finland , where the incidence is as high as 1.1 per 10,000 births. It is estimated that Meckel syndrome accounts for 5% of all neural tube defects there.[9]

The Leicestershire Perinatal Mortality Survey for the years 1976 to 1982 had found high incidences of Meckel syndrome in Gujarati Indian immigrants.[10]

References

- ↑ synd/2055 at Who Named It?

- ↑ J. F. Meckel. Beschreibung zweier durch sehr ähnliche Bildungsabweichungen entstellter Geschwister. Deutsches Archiv für Physiologie, 1822, 7: 99–172.

- ↑ G. B. Gruber. Beiträge zur Frage "gekoppelter" Missbildungen (Akrocephalossyndactylie und Dysencephalia splancnocystica. Beitr path Anat, 1934, 93: 459–476.

- ↑ "The Meckel–Gruber Syndrome proteins MKS1 and meckelin interact and are required for primary cilium formation". Human Molecular Genetics 16 (2): 173–186. 2007. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl459. PMID 17185389. http://hmg.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/short/16/2/173?rss=1.

- ↑ Badano, Jose L.; Norimasa Mitsuma; Phil L. Beales; Nicholas Katsanis (Sep 2006). "The Ciliopathies : An Emerging Class of Human Genetic Disorders". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 7: 125–148. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. PMID 16722803. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ↑ Kyttälä, Mira (May 2006) (pdf). Identification of the Meckel Syndrome Gene (MKS1) Exposes a Novel Ciliopathy. National Public Health Institute, Helsinki. Archived from the original on 2006-07-21. https://web.archive.org/web/20060721230538/http://www.ktl.fi/attachments/suomi/julkaisut/julkaisusarja_a/2006/2006a05.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ↑ Bergsma, D. (1979). "Birth Defects". Atlas and Compendium. London: Macmillan Press.

- ↑ Salonen, R.; Norio, R.; Reynolds, James F. (1984). "The Meckel syndrome: Clinicopathological Findings in 67 Patients". American Journal of Medical Genetics 18 (4): 671–689. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320180414. PMID 6486167.

- ↑ Nyberg, D. A. (1990). "Meckel–Gruber syndrome; Importance of Prenatal Diagnosis". Journal of Ultrasound Medicine 9: 691–696.

- ↑ Young, I. D.; Rickett, A. B.; Clarke, M. (1985-08-01). "High incidence of Meckel's syndrome in Gujarati Indians." (in en). Journal of Medical Genetics 22 (4): 301–304. doi:10.1136/jmg.22.4.301. ISSN 0022-2593. PMID 4045959. PMC 1049454. http://jmg.bmj.com/content/22/4/301.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |