Medicine:Psychological pain

| Psychological pain | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Suffering, mental agony, mental pain, emotional pain, algopsychalia, psychic pain, social pain, spiritual pain, soul pain |

| |

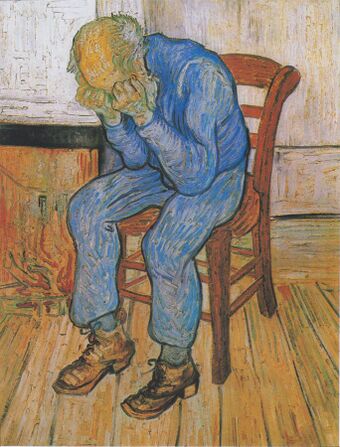

| Vincent van Gogh's 1890 painting Sorrowing old man ('At Eternity's Gate'), where a man weeps due to the unpleasant feelings of psychological pain. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, psychology |

| Medication | Antidepressant medication, Analgesic medication |

Psychological pain, mental pain, or emotional pain is an unpleasant feeling (a suffering) of a psychological, non-physical origin. A pioneer in the field of suicidology, Edwin S. Shneidman, described it as "how much you hurt as a human being. It is mental suffering; mental torment."[1] There is no shortage in the many ways psychological pain is referred to, and using a different word usually reflects an emphasis on a particular aspect of mind life. Technical terms include algopsychalia and psychalgia,[2] but it may also be called mental pain,[3][4] emotional pain,[5] psychic pain,[6][7] social pain,[8] spiritual or soul pain,[9] or suffering.[10][11] While these clearly are not equivalent terms, one systematic comparison of theories and models of psychological pain, psychic pain, emotional pain, and suffering concluded that each describe the same profoundly unpleasant feeling.[12] Psychological pain is widely believed to be an inescapable aspect of human existence.[13]

Other descriptions of psychological pain are "a wide range of subjective experiences characterized as an awareness of negative changes in the self and in its functions accompanied by negative feelings",[14] "a diffuse subjective experience ... differentiated from physical pain which is often localized and associated with noxious physical stimuli",[15] and "a lasting, unsustainable, and unpleasant feeling resulting from negative appraisal of an inability or deficiency of the self."[12]

Cause

The adjective 'psychological' is thought to encompass the functions of beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors,[16] which may be seen as an indication for the many sources of psychological pain. One way of grouping these different sources of pain was offered by Shneidman, who stated that psychological pain is caused by frustrated psychological needs.[1] For example, the need for love, autonomy, affiliation, and achievement, or the need to avoid harm, shame, and embarrassment. Psychological needs were originally described by Henry Murray in 1938 as needs that motivate human behavior.[17] Shneidman maintained that people rate the importance of each need differently, which explains why people's level of psychological pain differs when confronted with the same frustrated need. This needs perspective coincides with Patrick David Wall's description of physical pain that says that physical pain indicates a need state much more than a sensory experience.[18]

Unmet psychological needs in youth may cause an inability to meet human needs later in life.[19] As a consequence of neglectful parenting, children with unmet psychological needs may be linked to psychotic disorders in childhood throughout life.[20]

In the fields of social psychology and personality psychology, the term social pain is used to denote psychological pain caused by harm or threat to social connection; bereavement, embarrassment, shame and hurt feelings are subtypes of social pain.[21] From an evolutionary perspective, psychological pain forces the assessment of actual or potential social problems that might reduce the individual's fitness for survival.[22] The way people display their psychological pain socially (for example, crying, shouting, moaning) serves the purpose of indicating that they are in need.

Neuropsychology

Physical pain and psychological pain share common underlying neurological mechanisms.[23][15][24][25] Brain regions that were consistently found to be implicated in both types of pain are the anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal cortex (some subregions more than others), and may extend to other regions as well. Brain regions that were also found to be involved in psychological pain include the insular cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, parahippocampal gyrus, basal ganglia, and cerebellum. Some advocate that, because similar brain regions are involved in both physical pain and psychological pain, pain should be seen as a continuum that ranges from purely physical to purely psychological.[26] Moreover, many sources mention the fact that many metaphors of physical pain are used to refer to psychologically painful experiences.[8][12][27] Further connection between physical and psychological pain has been supported through proof that acetaminophen, an analgesic, can suppress activity in the anterior cingulate cortex and the insular cortex when experiencing social exclusion, the same way that it suppresses activity when experiencing physical pain,[28][29] and reduces the agitation of people with dementia.[30][31] However, use of paracetamol for more general psychological pain remains disputed.[32]

Borderline personality disorder

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) has long been believed to be a disorder that produces the most intense emotional pain and distress in those who have this condition. Studies have shown that borderline patients experience chronic and significant emotional suffering and mental agony.[33][34] Borderline patients may feel overwhelmed by negative emotions, experiencing intense grief instead of sadness, shame and humiliation instead of mild embarrassment, rage instead of annoyance, and panic instead of nervousness.[35] People with BPD are especially sensitive to feelings of rejection, isolation and perceived failure.[36] Both clinicians and laymen alike have witnessed the desperate attempts to escape these subjective inner experiences of these patients. Borderline patients are severely impulsive and their attempts to alleviate the agony are often very destructive or self-destructive. Suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and bulimia nervosa), self-harm (cutting, overdosing, starvation, etc.), compulsive spending, gambling, sex addiction, violent and aggressive behavior, sexual promiscuity and deviant sexual behaviors, are desperate attempts to escape this pain.

The intrapsychic pain experienced by those diagnosed with BPD has been studied and compared to normal healthy controls and to others with major depression, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder, schizophrenia, other personality disorders, and a range of other conditions. Although the excruciatingly painful inner experience of the borderline patient is both unique and perplexing, it is often linked to severe childhood trauma of abuse and neglect. In clinical populations, the rate of suicide of patients with borderline personality disorder is estimated to be 10%, a rate far greater than that in the general population and still considerably greater than for patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. However, 60–70% of patients with borderline personality disorder make suicide attempts, so suicide attempts are far more frequent than completed suicides in patients with BPD.[37]

The intense dysphoric states which patients diagnosed with BPD endure on a regular basis distinguishes them from those with other personality disorders: major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and virtually all known DSM-IV Axis I and Axis II conditions. In a 1998 study entitled "The Pain of Being Borderline: Dysphoric States Specific to Borderline Personality Disorder", 146 diagnosed borderline patients took a 50-item self-report measure test. The conclusions from this study suggest "that the subjective pain of borderline patients may be both more pervasive and more multifaceted than previously recognised and that the overall "amplitude" of this pain may be a particularly good marker for the borderline diagnosis".[38]

Feelings of emptiness are a central problem for patients with personality disturbances. In an attempt to avoid this feeling, these patients employ defences to preserve their fragmentary selves. Feelings of emptiness may be so painful that suicide is considered.[39]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Appendix A Psychological Pain Survey". The Suicidal Mind. Oxford University Press. 1996. pp. 173. ISBN 9780195118018. https://books.google.com/books?id=rn4pf7-dca0C.

- ↑ Psychalgia: mental distress. Merriam-Webster's Medical Dictionary. But see also psychalgia in the sense of psychogenic pain.

- ↑ "Bodily pain and mental pain". The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 15: 1–13. 1934. http://www.pep-web.org/document.php?id=ijp.015.0001a.

- ↑ "Mental pain and its relationship to suicidality and life meaning". Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 33 (3): 231–41. 2003. doi:10.1521/suli.33.3.231.23213. PMID 14582834.

- ↑ "Grounded theory analysis of emotional pain". Psychotherapy Research 9 (3): 342–62. 1999. doi:10.1080/10503309912331332801. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10503309912331332801.

- ↑ "On the concept of pain, with special reference to depression and psychogenic pain". Journal of Psychosomatic Research 11 (1): 69–75. 1967. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(67)90058-X. PMID 6049033.

- ↑ "Why does "pain management" exclude psychic pain?". Issues in Mental Health Nursing 30 (5): 344. May 2009. doi:10.1080/01612840902844890. PMID 19437255. http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/M_Shattell_Why_2009_EMBARGO%20TIL%20MAY%202010.pdf.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain". Psychological Bulletin 131 (2): 202–23. March 2005. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.202. PMID 15740417. http://www.sozialpsychologie.uni-frankfurt.de/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/MacDonald-Leary-20051.pdf.

- ↑ Spiritual pain: 60,000 Google results. Soul pain: 237,000 Google results.

- ↑ "Toward a praxis theory of suffering". Advances in Nursing Science 24 (1): 47–59. September 2001. doi:10.1097/00012272-200109000-00007. PMID 11554533.

- ↑ "The progression of suffering implies alleviated suffering". Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 18 (3): 264–72. September 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00281.x. PMID 15355520.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Toward a unifying definition of psychological pain". Journal of Loss & Trauma 16 (5): 402–12. 2011. doi:10.1080/15325024.2011.572044. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15325024.2011.572044#preview.

- ↑ "On the capacity to endure psychic pain". The Scandinavian Psychoanalytic Review 34: 23–30. 2011. doi:10.1080/01062301.2011.10592880. http://www.pep-web.org/document.php?id=spr.034.0023a.

- ↑ "Mental pain: a multidimensional operationalization and definition". Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 33 (3): 219–30. 2003. doi:10.1521/suli.33.3.219.23219. PMID 14582833.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Psychological pain: a review of evidence". Journal of Psychiatric Research 40 (8): 680–90. December 2006. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.03.003. PMID 16725157.

- ↑ "Psychogenic pain-what it means, why it does not exist, and how to diagnose it". Pain Medicine 1 (4): 287–94. December 2000. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.00049.x. PMID 15101873.

- ↑ Explorations in personality (70 ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-0-19-530506-7.

- ↑ "On the relation of injury to pain". Pain 6 (3): 253–64. 1979. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(79)90047-2. PMID 460933.

- ↑ Sheppard, R.; Deane, F. P.; Ciarrochi, J. (2018). "Unmet need for professional mental health care among adolescents with high psychological distress". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 52 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1177/0004867417707818. PMID 28486819. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28486819/#:~:text=Compared%20to%20cases%20with%20partially,management%20and%20concerns%20regarding%20stigma.

- ↑ DeVylder, Jordan E.; Oh, Hans Y.; Corcoran, Cheryl M.; Lukens, Ellen P. (June 20, 2014). "Treatment Seeking and Unmet Need for Care Among Persons Reporting Psychosis-Like Experiences". Psychiatric Services 65 (6): 774–780. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201300254. PMID 24534875.

- ↑ "Social Pain and Hurt Feelings". Cambridge Handbook of Personality Psychology. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. 2009. ISBN 9780521680516. http://web.psych.utoronto.ca/gmacdonald/macdonald_social_pain_chapter.pdf.

- ↑ "The Evolution of Psychological Pain". Sociobiology and the Social Sciences. Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University Press. 1989. ISBN 978-0-89672-161-6. https://archive.org/details/sociobiologysoci0000unse.

- ↑ "The neural bases of social pain: evidence for shared representations with physical pain". Psychosomatic Medicine 74 (2): 126–35. 2012. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182464dd1. PMID 22286852.

- ↑ "Why rejection hurts: a common neural alarm system for physical and social pain". Trends in Cognitive Sciences 8 (7): 294–300. July 2004. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.05.010. PMID 15242688.

- ↑ "Brain regions associated with psychological pain: implications for a neural network and its relationship to physical pain". Brain Imaging and Behavior 7 (1): 1–14. March 2013. doi:10.1007/s11682-012-9179-y. PMID 22660945.

- ↑ "Is there such a thing as psychological pain? And why it matters". Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 34 (4): 658–67. December 2010. doi:10.1007/s11013-010-9190-y. PMID 20835887.

- ↑ "Heartbreak and physical pain linked in brain". Issues in Mental Health Nursing 32 (12): 789–91. 2011. doi:10.3109/01612840.2011.583714. PMID 22077752.

- ↑ "Acetaminophen reduces social pain: behavioral and neural evidence". Psychological Science 21 (7): 931–7. July 2010. doi:10.1177/0956797610374741. PMID 20548058.

- ↑ "The common pain of surrealism and death: acetaminophen reduces compensatory affirmation following meaning threats". Psychological Science 24 (6): 966–73. June 2013. doi:10.1177/0956797612464786. PMID 23579320.

- ↑ "Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomised clinical trial". BMJ 343: d4065. July 2011. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4065. PMID 21765198.

- ↑ "Reducing agitation through pain relief - Living with dementia magazine October 2011 - Alzheimer's Society". alzheimers.org.uk. http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=1713&pageNumber=3.

- ↑ "Don't take paracetamol for painful emotions". www.nhs.uk. 2013-04-22. http://www.nhs.uk/news/2013/04April/Pages/paracetamol-not-recommended-for-painful-emotions.aspx.

- ↑ "Enhanced 'Reading the Mind in the Eyes' in borderline personality disorder compared to healthy controls". Psychological Medicine 39 (12): 1979–88. December 2009. doi:10.1017/S003329170900600X. PMID 19460187.

- ↑ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994. ISBN 978-0-89-042061-4. https://archive.org/details/diagnosticstati00amer.

- ↑ Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press. 1993. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-89862-183-9.

- ↑ "Aversive tension in patients with borderline personality disorder: a computer-based controlled field study". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 111 (5): 372–9. May 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00466.x. PMID 15819731.

- ↑ "Borderline personality disorder and suicidality". The American Journal of Psychiatry 163 (1): 20–6. January 2006. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.20. PMID 16390884.

- ↑ "The pain of being borderline: dysphoric states specific to borderline personality disorder". Harvard Review of Psychiatry 6 (4): 201–7. 1998. doi:10.3109/10673229809000330. PMID 10370445.

- ↑ "The Experience of Emptiness in Narcissistic and Borderline States: II. The Struggle for a Sense of Self and the Potential for Suicide". International Review of Psycho-Analysis 4 (4): 471–479. 1977. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1979-13573-001. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

|