Medicine:Savant syndrome

| Savant syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Autistic savant, savant syndrome (historical)[1] |

| |

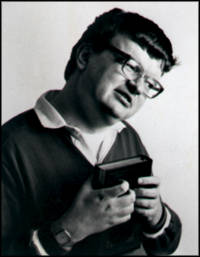

| Kim Peek, the savant who was the inspiration for the main character in the movie Rain Man | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology |

| Symptoms | General mental disability with certain abilities far in excess of average[1][2] |

| Types | Congenital, acquired[3] |

| Causes | Neurodevelopmental disorder such as autism spectrum disorder, brain injury[1] |

| Frequency | ~1 in a million people[4] |

Savant syndrome (/sæˈvɑːnt, səˈvɑːnt, ˈsævənt/) is a phenomenon where someone demonstrates exceptional aptitude in one domain, such as art or mathematics, despite significant social or intellectual impairment.[1]

Those with the condition generally have a neurodevelopmental disorder such as autism spectrum disorder or have experienced a brain injury.[1] About half of cases are associated with autism, and these individuals may be known as Autistic savant (fr)[1] While the condition usually becomes apparent in childhood, some cases develop later in life.[1] It is not recognized as a mental disorder within the DSM-5, as it relates to parts of the brain healing or restructuring.[5]

Savant syndrome is estimated to affect around one in a million people.[4] The condition affects more males than females, at a ratio of 6:1.[1] The first medical account of the condition was in 1783.[1] Approximately half of savants are autistic; the other half often have some form of central nervous system injury or disease.[1] It is estimated that between 0.5% up to 10% of those with autism have some form of savant abilities.[1][6][7] It is estimated that there are fewer than a hundred prodigious savants, with skills so extraordinary that they would be considered spectacular even for a non-impaired person, currently living.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Savant skills are usually found in one or more of five major areas: art, memory, arithmetic, musical abilities, and spatial skills.[1] The most common kinds of savants are calendrical savants,[8][9] "human calendars" who can calculate the day of the week for any given date with speed and accuracy, or recall personal memories from any given date. Advanced memory is the key "superpower" in savant abilities.[8]

Calendrical savants

A calendrical savant (or calendar savant) is someone who – despite having an intellectual disability – can name the day of the week of a date, or vice versa, on a limited range of decades or certain millennia.[9][10] The rarity of human calendar calculators is possibly due to the lack of motivation to develop such skills among the general population, although mathematicians have developed formulas that allow them to obtain similar skills.[10] Calendrical savants, on the other hand, may not be prone to invest in socially engaging skills.[11]

Mechanism

Psychological

No widely accepted cognitive theory explains savants' combination of talent and deficit.[12] It has been suggested that individuals with autism are biased towards detail-focused processing and that this cognitive style predisposes individuals either with or without autism to savant talents.[13] Another hypothesis is that savants hyper-systemize, thereby giving an impression of talent. Hyper-systemizing is an extreme state in the empathizing–systemizing theory that classifies people based on their skills in empathizing with others versus systemizing facts about the external world.[14] Also, the attention to detail of savants is a consequence of enhanced perception or sensory hypersensitivity in these unique individuals.[14][15] It has also been hypothesized that some savants operate by directly accessing deep, unfiltered information that exists in all human brains that is not normally available to conscious awareness.[16]

Neurological

In some cases, savant syndrome can be induced following severe head trauma to the left anterior temporal lobe.[1] Savant syndrome has been artificially replicated using low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation to temporarily disable this area of the brain.[17]

Epidemiology

There are no objectively definitive statistics about how many people have savant skills. The estimates range from "exceedingly rare"[18] to one in ten people with autism having savant skills in varying degrees.[1] A 2009 British study of 137 parents of autistic children found that 28% believe their children met the criteria for a savant skill, defined as a skill or power "at a level that would be unusual even for 'normal' people".[19] As many as 50 cases of sudden or acquired savant syndrome have been reported.[20][21]

Males diagnosed with savant syndrome outnumber females by roughly 6:1 (in Finland ),[22] slightly higher than the sex ratio disparity for autism spectrum disorders of 4.3:1.[23]

History

The term idiot savant (French for "learned idiot") was first used to describe the condition in 1887 by John Langdon Down, who is known for his description of Down syndrome. The term idiot savant was later described as a misnomer because not all reported cases fit the definition of idiot, originally used for a person with a very severe intellectual disability. The term autistic savant (fr) was also used as a description of the disorder. Like idiot savant, the term came to be considered a misnomer because only half of those who were diagnosed with savant syndrome were autistic. Upon realization of the need for accuracy of diagnosis and dignity towards the individual, the term savant syndrome became widely accepted terminology.[1][18]

Society and culture

Notable cases

- Daniel Tammet, British author and polyglot

- Derek Paravicini, British blind musical prodigy and pianist

- Henriett Seth F., Hungarian autistic writer and artist

- Nadia Chomyn, British autistic artist.

- Kim Peek, American "megasavant"

- Leslie Lemke, American musician

- Rex Lewis-Clack, American pianist and musical savant

- Matt Savage, American musician

- Stephen Wiltshire, British architectural artist

- Temple Grandin,[24] American professor of animal science

- David M. Nisson, American scientist[25]

- Tom Wiggins, American blind pianist and composer[26]

- Tommy McHugh, British artist and poet

- Kodi Lee, 2019 America's Got Talent winner (musician)

Acquired cases

- Alonzo Clemons, American acquired savant sculptor

- Anthony Cicoria, American acquired savant pianist and medical doctor

- Derek Amato, American acquired savant composer and pianist

- Patrick Fagerberg, American acquired savant artist, inventor and former lawyer

- Orlando Serrell, American acquired savant

- Jason Padgett, American acquired savant and artist

Fictional cases

- Shaun Murphy, autistic savant in the 2017 American medical drama television series The Good Doctor.

- Raymond Babbitt, autistic savant in the 1988 film Rain Man (inspired by Kim Peek)

- Park Shi-on, autistic savant in the 2013 South Korean medical drama Good Doctor

- Kazan, autistic savant in the 1997 film Cube

- Kazuo Kiriyama, main antagonist in the Japan 1999 novel Battle Royale

- Jeong Jae-hee, autistic savant in the 2021 South Korean psychological drama Mouse

- Patrick Obyedkov, acquired savant in a 2007 episode of the U.S. medical drama House.

- Woo Young-woo, autistic savant in the 2022 South Korean legal drama Extraordinary Attorney Woo.

- Mashiro Shiina, savant in the 2012 anime series The Pet Girl of Sakurasou.

- Ali Vefa, autistic savant in the 2019 Turkish medical drama Mucize Doktor, based on the South Korean series Good Doctor.

See also

- Autistic art

- Child prodigy

- Creativity and mental illness

- Wise fool

- Idiot

- Mental calculator

- Hyperthymesia

- Ideasthesia

- Twice exceptional

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 "The savant syndrome: an extraordinary condition. A synopsis: past, present, future". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1351–7. May 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0326. PMID 19528017.

- ↑ "The savant syndrome: intellectual impairment and exceptional skill". Psychological Bulletin 125 (1): 31–46. January 1999. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.1.31. PMID 9990844.

- ↑ "The Savant Syndrome and Its Possible Relationship to Epilepsy". Neurodegenerative Diseases. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 724. 2012. pp. 332–43. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0653-2_25. ISBN 978-1-4614-0652-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hyltenstam, Kenneth (2016). Advanced Proficiency and Exceptional Ability in Second Languages. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 258. ISBN 9781614515173. https://books.google.com/books?id=DOfCDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA258. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ Sperry, Len (2015). Mental Health and Mental Disorders: An Encyclopedia of Conditions, Treatments, and Well-Being [3 volumes: An Encyclopedia of Conditions, Treatments, and Well-Being]. ABC-CLIO. p. 969. ISBN 9781440803833. https://books.google.com/books?id=NzgVCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA969. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ Treffert, Darold A.. "The Autistic Savant". Wisconsin Medical Society. https://www.wisconsinmedicalsociety.org/professional/savant-syndrome/resources/articles/the-autistic-savant/. Retrieved 2014-07-24.

- ↑ "Savant Syndrome Statistics". Health Research Funding. 2014-07-12. http://healthresearchfunding.org/savant-syndrome-statistics/. Retrieved 2014-07-24.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Incidence of Savant Syndrome in Finland". Perceptual and Motor Skills 91 (1): 120–2. August 2000. doi:10.2466/pms.2000.91.1.120. PMID 11011882.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "An analysis of calendar performance in two autistic calendar savants". Learning & Memory 14 (8): 533–8. August 2007. doi:10.1101/lm.653607. PMID 17686947.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Cowan, Richard; Carney, Daniel P. J. (June 2006). "Calendrical savants: Exceptionality and Practice". Cognition 100 (2): B1–B9. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2005.08.001. PMID 16157326. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1488985/. Retrieved 2021-08-24.

- ↑ "Do calendrical savants use calculation to answer date questions? A functional magnetic resonance imaging study". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1417–24. May 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0323. PMID 19528025.

- ↑ Pring, Linda (2005). "Savant talent". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 47 (7): 500–503. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2005.tb01180.x. PMID 15991873.

- ↑ "What aspects of autism predispose to talent?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences (The Economist) 364 (1522): 1369–75. May 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0332. PMID 19528019. PMC 2677590. http://www.economist.com/science/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13489714. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Talent in autism: hyper-systemizing, hyper-attention to detail and sensory hypersensitivity". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1377–83. May 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0337. PMID 19528020.

- ↑ "Enhanced perception in savant syndrome: patterns, structure and creativity". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1385–91. May 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0333. PMID 19528021.

- ↑ "Explaining and inducing savant skills: privileged access to lower level, less-processed information". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences (The Economist) 364 (1522): 1399–405. May 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0290. PMID 19528023. PMC 2677578. http://www.economist.com/science/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13489714. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ↑ "Explaining and inducing savant skills: privileged access to lower level, less-processed information". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1399–405. May 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0290. PMID 19528023.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hiles, Dave (2001). "Savant Syndrome". De Montfort University. http://www.psy.dmu.ac.uk/drhiles/Savant%20Syndrome.htm.

- ↑ "Savant skills in autism: psychometric approaches and parental reports". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences (The Economist) 364 (1522): 1359–67. May 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0328. PMID 19528018. PMC 2677586. http://www.economist.com/science/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13489714. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ↑ Yant-Kinney, Monica (2012-08-20). "An artist is born after car crash". The Inquirer (Philadelphia). http://articles.philly.com/2012-08-20/news/33273378_1_brain-injury-owens-answers-car-crash/2.

- ↑ "'A ski accident left me with advanced mental abilities': US woman tells her extraordinary story". Daily Telegraph. 17 April 2015. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/11544405/A-ski-accident-left-me-with-advanced-mental-abilities-US-woman-tells-her-extraordinary-story.html.

- ↑ Treffert, Darold. A Visual Feast

- ↑ "The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders". Annual Review of Public Health 28: 235–58. 2007. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007. PMID 17367287.

- ↑ McGowan, Kat (March 13, 2013). "Exploring Temple Grandin's Brain". Discover Magazine. http://discovermagazine.com/2013/april/2-exploring-temple-grandins-brain. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ↑ "The Physics of Success". March 23, 2016. https://stories.ucdavis.edu/stories/students/nisson.html.

- ↑ Badcock, Christopher (2009). The Imprinted Brain: How Genes Set the Balance Between Autism and Psychosis. London: Jessica Kingsley. p. 29. ISBN 9781849050234. https://books.google.com/books?id=PG0uZ5UnuFEC&q=Wiggins&pg=PA29. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|