Medicine:Sensory processing disorder

This article may contain an excessive number of citations. (October 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

}}

| Sensory processing disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sensory integration dysfunction |

| |

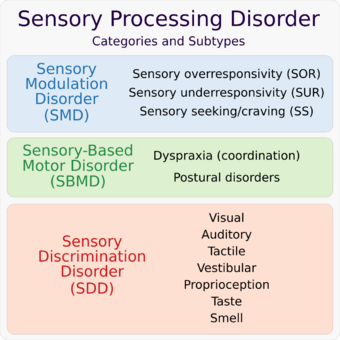

| An SPD nosology proposed by Miller LJ et al. (2007)[1] | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, occupational therapy, neurology |

| Symptoms | Hypersensitivity and hyposensitivity to stimuli, and/or difficulties using sensory information to plan movement. Problems discriminating characteristics of stimuli. |

| Complications | Low school performance, behavioral difficulties, social isolation, employment problems, family and personal stress |

| Usual onset | Uncertain |

| Risk factors | Anxiety, behavioral difficulties |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms |

| Treatment | |

Sensory processing disorder (SPD), formerly known as sensory integration dysfunction, is a condition in which multisensory input is not adequately processed in order to provide appropriate responses to the demands of the environment. Sensory processing disorder is present in many people with dyspraxia, autism spectrum disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Individuals with SPD may inadequately process visual, auditory, olfactory (smell), gustatory (taste), tactile (touch), vestibular (balance), proprioception (body awareness), and interoception (internal body senses) sensory stimuli.

Sensory integration was defined by occupational therapist Anna Jean Ayres in 1972 as "the neurological process that organizes sensation from one's own body and from the environment and makes it possible to use the body effectively within the environment".[2][3] Sensory processing disorder has been characterized as the source of significant problems in organizing sensation coming from the body and the environment and is manifested by difficulties in the performance in one or more of the main areas of life: productivity, leisure and play[4] or activities of daily living.[5]

Sources debate whether SPD is an independent disorder or represents the observed symptoms of various other, more well-established, disorders.[6][7][8][9] SPD is not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association,[10][11] and the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended in 2012 that pediatricians not use SPD as a stand-alone diagnosis.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Sensory integration difficulties or sensory processing disorder (SPD) are characterized by persistent challenges with neurological processing of sensory stimuli that interfere with a person's ability to participate in everyday life. Such challenges can appear in one or several sensory systems of the somatosensory system, vestibular system, proprioceptive system, interoceptive system, auditory system, visual system, olfactory system, and gustatory system. [12]

While many people can present one or two symptoms, sensory processing disorder has to have a clear functional impact on the person's life.[13]

Signs of over-responsivity,[14] including, for example, dislike of textures such as those found in fabrics, foods, grooming products or other materials found in daily living, to which most people would not react, and serious discomfort, sickness or threat induced by normal sounds, lights, ambient temperature, movements, smells, tastes, or even inner sensations such as heartbeat. Signs of under-responsivity, including sluggishness and lack of responsiveness.

Sensory cravings,[15] including, for example, fidgeting, impulsiveness, or seeking or making loud, disturbing noises; and sensorimotor-based problems, including slow and uncoordinated movements or poor handwriting.

Relationship to other disorders

Sensory integration and processing difficulties can be a feature of a number of disorders, including anxiety problems, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),[16] food intolerances, behavioral disorders, and particularly, autism spectrum disorder (ASD).[17][18][19] This pattern of comorbidities poses a significant challenge to those who claim that SPD is an identifiably specific disorder, rather than simply a term given to a set of symptoms common to other disorders.[20]

Two studies have provided preliminary evidence suggesting that there may be measurable neurological differences between children diagnosed with SPD and control children classified as neurotypical[21] or children diagnosed with autism.[22] Despite this evidence, that SPD researchers have yet to agree on a proven, standardized diagnostic tool undermines researchers' ability to define the boundaries of the disorder and makes correlational studies, like those on structural brain abnormalities, less convincing.[23]

Causes

The exact cause of SPD is not known.[24] However, it is known that the midbrain and brainstem regions of the central nervous system are early centers in the processing pathway for multisensory integration; these brain regions are involved in processes including coordination, attention, arousal, and autonomic function.[25] After sensory information passes through these centers, it is then routed to brain regions responsible for emotions, memory, and higher level cognitive functions.

Mechanism

Research in sensory processing in 2007 is focused on finding the genetic and neurological causes of SPD. Electroencephalography (EEG),[26] measuring event-related potential (ERP), and magnetoencephalography (MEG) are traditionally used to explore the causes behind the behaviors observed in SPD.

Differences in tactile and auditory over-responsivity show moderate genetic influences, with tactile over-responsivity demonstrating greater heritability.[27] Differences in auditory latency (the time between the input is received and when reaction is observed in the brain), hypersensitivity to vibration in the Pacinian corpuscles receptor pathways, and other alterations in unimodal and multisensory processing have been detected in autism populations.[28]

People with sensory processing deficits appear to have less sensory gating than typical subjects,[29][30] and atypical neural integration of sensory input. In people with sensory over-responsivity, different neural generators activate, causing the automatic association of causally related sensory inputs that occurs at this early sensory-perceptual stage to not function properly.[31] People with sensory over-responsivity might have increased D2 receptor in the striatum, related to aversion to tactile stimuli, and reduced habituation. In animal models, prenatal stress significantly increased tactile avoidance.[32]

Recent research has also found an abnormal white matter microstructure in children with SPD, compared with typical children and those with other developmental disorders such as autism and ADHD.[33][34]

One hypothesis is that multisensory stimulation may activate a higher-level system in the frontal cortex that involves attention and cognitive processing, rather than the automatic integration of multisensory stimuli observed in typically developing adults in the auditory cortex.[28][31]

Diagnosis

Sensory processing disorder is accepted in the Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood (DC:0-3R). It is not recognized as a mental disorder in medical manuals such as the ICD-10[35] or the DSM-5.[36]

There is not a single test to diagnose sensory processing disorder. Diagnosis is primarily arrived at by the use of standardized tests, standardized questionnaires, expert observational scales, and free-play observation at an occupational therapy gym. Observation of functional activities might be carried at school and home as well.[37]

Though diagnosis in most of the world is done by an occupational therapist, in some countries diagnosis is made by certified professionals, such as psychologists, learning specialists, physiotherapists and/or speech and language therapists.[38] Some countries recommend to have a full psychological and neurological evaluation if symptoms are too severe.

Standardized tests

- Sensory Integration and Praxis Test (SIPT)

- Evaluation of Ayres' Sensory Integration (EASI) – in development

- DeGangi-Berk Test of Sensory Integration (TSI)

- Test of Sensory Functions in Infants (TSFI)[39]

Standardized questionnaires

- Sensory Profile (SP)[40]

- Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile[39]

- Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile

- Sensory Profile School Companion

- Indicators of Developmental Risk Signals (INDIPCD-R)[41]

- Sensory Processing Measure (SPM)[42]

- Sensory Processing Measure Preschool (SPM-P)[43]

Classification

Sensory integration and processing difficulties

Construct-related evidence relating to sensory integration and processing difficulties from Ayres' early research emerged from factor analysis of the earliest test the SCISIT and Mulligan's 1998 "Patterns of Sensory Integration Dysfunctions: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis".[44] Sensory integration and processing patterns recognised in the research support a classification of difficulties related to:

- Sensory registration and perception (discrimination)

- Sensory reactivity (modulation)

- Praxis (meaning "to do")

- Postural, ocular and bilateral integration

Sensory processing disorder (SPD)

Proponents of a new nosology SPD have instead proposed three categories: sensory modulation disorder, sensory-based motor disorders and sensory discrimination disorders[1] (as defined in the Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders in Infancy and Early Childhood).[45][46]

1. Sensory modulation disorder (SMD)

Sensory modulation refers to a complex central nervous system process[1][47] by which neural messages that convey information about the intensity, frequency, duration, complexity, and novelty of sensory stimuli are adjusted. [48]

SMD consists of three subtypes:

- Sensory over-responsivity.

- Sensory under-responsivity

- Sensory craving/seeking.

2. Sensory-based motor disorder (SBMD)

According to proponents, sensory-based motor disorder shows motor output that is disorganized as a result of incorrect processing of sensory information affecting postural control challenges, resulting in postural disorder, or developmental coordination disorder.[1][49]

The SBMD subtypes are:

- Dyspraxia

- Postural disorder

3. Sensory discrimination disorder (SDD)

Sensory discrimination disorder involves the incorrect processing of sensory information.[1] The SDD subtypes are:[50]

- Visual

- Auditory

- Tactile

- Gustatory (taste)

- Olfactory (smell)

- Vestibular (balance, head position and movement in space)

- Proprioceptive (feeling of where parts of the body are located in space, muscle sensation)

- Interoception (inner body sensations).

Treatment

Sensory integration therapy

Typically offered as part of occupational therapy, ASI that places a child in a room specifically designed to stimulate and challenge all of the senses to elicit functional adaptive responses. Occupational therapy is defined by the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) as "Occupational therapy practitioners in pediatric settings work with children and their families, caregivers and teachers to promote participation in meaningful activities and occupations". In childhood, these occupations may include play, school and learning self-care tasks. An entry-level occupational therapist can provide treatment for sensory processing disorder; however, more advanced clinical training exists to target the underlying neuro-biological processes involved.[51] Although Ayres initially developed her assessment tools and intervention methods to support children with sensory integration and processing challenges, the theory is relevant beyond childhood.[52][53][54]

Sensory integration therapy is driven by four main principles:[55]

- Just right challenge (the child must be able to successfully meet the challenges that are presented through playful activities)

- Adaptive response (the child adapts their behavior with new and useful strategies in response to the challenges presented)

- Active engagement (the child will want to participate because the activities are fun)

- Child directed (the child's preferences are used to initiate therapeutic experiences within the session)

Serious questions have been raised as to the effectiveness of this therapy[56][57][58][59] particularly in medical journals where the requirements for a treatment to be effective is much higher and developed than its occupational therapy counterparts which often advocate the effectiveness of the treatment.[60][61]

Sensory processing therapy

This therapy retains all of the above-mentioned four principles and adds:[62]

- Intensity (person attends therapy daily for a prolonged period of time)

- Developmental approach (therapist adapts to the developmental age of the person, against actual age)

- Test-retest systematic evaluation (all clients are evaluated before and after)

- Process driven vs. activity driven (therapist focuses on the "just right" emotional connection and the process that reinforces the relationship)

- Parent education (parent education sessions are scheduled into the therapy process)

- "Joie de vivre" (happiness of life is therapy's main goal, attained through social participation, self-regulation, and self-esteem)

- Combination of best practice interventions (is often accompanied by integrated listening system therapy, floor time, and electronic media such as Xbox Kinect, Nintendo Wii, Makoto II machine training and others)

While occupational therapists using a sensory integration frame of reference work on increasing a child's ability to adequately process sensory input, other OTs may focus on environmental accommodations that parents and school staff can use to enhance the child's function at home, school, and in the community.[63][64] These may include selecting soft, tag-free clothing, avoiding fluorescent lighting, and providing ear plugs for "emergency" use (such as for fire drills).

Evaluation of treatment effectiveness

A 2019 review found sensory integration therapy to be effective for autism spectrum disorder.[65] Another study from 2018 backs up the intervention for children with special needs,[66] Additionally, the American Occupational Therapy Association supports the intervention.[67]

In its overall review of the treatment effectiveness literature, Aetna concluded that "The effectiveness of these therapies is unproven",[68] while the American Academy of Pediatrics concluded that "parents should be informed that the amount of research regarding the effectiveness of sensory integration therapy is limited and inconclusive."[69] A 2015 article concluded that SIT techniques exist "outside the bounds of established evidence-based practice" and that SIT is "quite possibly a misuse of limited resources."[70]

Epidemiology

It has been estimated by proponents that up to 16.5% of elementary school aged children present elevated SOR behaviors in the tactile or auditory modalities.[71] This figure is larger than what previous studies with smaller samples had shown: an estimate of 5–13% of elementary school aged children.[72] Critics have noted that such a high incidence for just one of the subtypes of SPD raises questions about the degree to which SPD is a specific and clearly identifiable disorder.[23]

Proponents have also claimed that adults may also show signs of sensory processing difficulties and would benefit for sensory processing therapies,[73] although this work has yet to distinguish between those with SPD symptoms alone vs adults whose processing abnormalities are associated with other disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder.[74]

Society and culture

The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) and British Royal College of Occupational Therapy (RCOT) support the use of a variety of methods of sensory integration for those with sensory integration and processing difficulties. Both organizations recognise the need for further research about Ayres' Sensory Integration and related approaches. In the USA this important to increase insurance coverage for related therapies. AOTA and RCOT have made efforts to educate the public about sensory Integration and related approaches. AOTA's practice guidelines and RCOT's informed view "Sensory Integration and sensory-based interventions"[75] currently support the use of sensory integration therapy and interprofessional education and collaboration in order to optimize treatment for those with sensory integration and processing difficulties. The AOTA provides several resources pertaining to sensory integration therapy, some of which includes a fact sheet, new research, and continuing education opportunities.[76]

Controversy

There are concerns regarding the validity of the diagnosis. SPD is not included in the DSM-5 or ICD-10, the most widely used diagnostic sources in healthcare. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 2012 stated that there is no universally accepted framework for diagnosis and recommends caution against using any "sensory" type therapies unless as a part of a comprehensive treatment plan. The AAP has plans to review its policy, though those efforts are still in the early stages.[77]

A 2015 article on Sensory Integration Therapy (SIT) concluded that SIT is "ineffective and that its theoretical underpinnings and assessment practices are unvalidated", that SIT techniques exist "outside the bounds of established evidence-based practice", and that SIT is "quite possibly a misuse of limited resources".[70]

Some sources point that sensory issues are an important concern, but not a diagnosis in themselves.[78][79]

Critics have noted that what proponents claim are symptoms of SPD are both broad and, in some cases, represent very common, and not necessarily abnormal or atypical, childhood characteristics. Where these traits become grounds for a diagnosis is generally in combination with other more specific symptoms or when the child gets old enough to explain that the reasons behind their behavior are specifically sensory.[80]

Manuals

SPD is in Stanley Greenspan's Diagnostic Manual for Infancy and Early Childhood and as Regulation Disorders of Sensory Processing part of The Zero to Three's Diagnostic Classification.

Is not recognized as a stand-alone diagnosis in the manuals ICD-10 or in the recently updated DSM-5, but unusual reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects is included as a possible but not necessary criterion for the diagnosis of autism.[81][80]

History

Sensory processing disorder as a specific form of atypical functioning was first described by occupational therapist Anna Jean Ayres (1920–1989).[82]

Original model

Ayres's theoretical framework for what she called Sensory Integration Dysfunction was developed after six factor analytic studies of populations of children with learning disabilities, perceptual motor disabilities and normal developing children.[83] Ayres created the following nosology based on the patterns that appeared on her factor analysis:

- Dyspraxia: poor motor planning (more related to the vestibular system and proprioception)

- Poor bilateral integration: inadequate use of both sides of the body simultaneously

- Tactile defensiveness: negative reaction to tactile stimuli

- Visual perceptual deficits: poor form and space perception and visual motor functions

- Somatodyspraxia: poor motor planning (related to poor information coming from the tactile and proprioceptive systems)

- Auditory-language problems

In 1998, Mulligan found a similar pattern of deficits in a confirmatory factor analytic study.[84][85]

Quadrant model

Dunn's nosology uses two criteria:[86] response type (passive vs. active) and sensory threshold to the stimuli (low or high) creating four subtypes or quadrants:[87]

- High neurological thresholds

- Low registration: high threshold with passive response. Individuals who do not pick up on sensations and therefore partake in passive behavior.[88]

- Sensation seeking: high threshold and active response. Those who actively seek out a rich sensory filled environment.[88]

- Low neurological threshold

- Sensitivity to stimuli: low threshold with passive response. Individuals who become distracted and uncomfortable when exposed to sensation but do not actively limit or avoid exposure to the sensation.[88]

- Sensation avoiding: low threshold and active response. Individuals actively limit their exposure to sensations and are therefore high self regulators.[88]

Sensory processing model

In Miller's nosology "sensory integration dysfunction" was renamed into "Sensory processing disorder" to facilitate coordinated research work with other fields such as neurology since "the use of the term sensory integration often applies to a neurophysiologic cellular process rather than a behavioral response to sensory input as connoted by Ayres."[1]

The sensory processing model's nosology divides SPD in three subtypes: modulation, motor based and discrimination problems.[1]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Concept evolution in sensory integration: a proposed nosology for diagnosis". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 61 (2): 135–40. 2007. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.135. PMID 17436834.

- ↑ Sensory integration and learning disorders. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. 1972. ISBN 978-0-87424-303-1. OCLC 590960. https://archive.org/details/sensoryintegrati00ayre.

- ↑ "Types of sensory integrative dysfunction among disabled learners". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 26 (1): 13–8. 1972. PMID 5008164.

- ↑ "Sensory processing disorders and social participation". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 64 (3): 462–73. 2010. doi:10.5014/ajot.2010.09076. PMID 20608277.

- ↑ "Sensory Processing Disorder Explained". SPD Foundation. http://www.spdfoundation.net/about-sensory-processing-disorder.html.

- ↑ Brout, Jennifer; Miller, Lucy Jane. "DSM-5 Application for Sensory Processing Disorder Appendix A (part 1)". https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285591455.

- ↑ Arky, Beth. "The Debate Over Sensory Processing". https://childmind.org/article/the-debate-over-sensory-processing/.

- ↑ Walbam, K. (2014). The Relevance of Sensory Processing Disorder to Social Work Practice: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 31(1), 61-70. doi:10.1007/s10560-013-0308-2

- ↑ "AAP Recommends Careful Approach to Using Sensory-Based Therapies" (in en-US). https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/pages/AAP-Recommends-Careful-Approach-to-Using-Sensory-Based-Therapies.aspx.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Neale, Todd (June 2012). "AAP: Don't Use Sensory Disorder Diagnosis". Everyday Health. https://www.medpagetoday.com/pediatrics/generalpediatrics/33018.

- ↑ Weinstein, Edie (2016-11-22). "Making Sense of Sensory Processing Disorder". https://psychcentral.com/lib/making-sense-of-sensory-processing-disorder/.

- ↑ Galiana-Simal, A., Vela-Romero, M., Romero-Vela, V. M., Oliver-Tercero, N., García-Olmo, V., Benito-Castellanos, P. J., Muñoz-Martinez, V., & Beato-Fernandez, L. (2020). Sensory processing disorder: Key points of a frequent alteration in neurodevelopmental disorders. Cogent Medicine, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2020.1736829

- ↑ Mulligan, Shelley; Douglas, Sarah; Armstrong, Caitlin (2021-04-28). "Characteristics of Idiopathic Sensory Processing Disorder in Young Children". Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 15. doi:10.3389/fnint.2021.647928. ISSN 1662-5145. PMID 33994966.

- ↑ "Trajectories of Sensory Over-Responsivity from Early to Middle Childhood: Birth and Temperament Risk Factors". PLOS ONE 10 (6). 2015-06-24. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129968. PMID 26107259. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1029968V.

- ↑ "Longitudinal follow-up of autism spectrum features and sensory behaviors in Angelman syndrome by deletion class". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 53 (2): 152–9. February 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02455.x. PMID 21831244.

- ↑ "Sensory processing problems in children with ADHD, a systematic review". Psychiatry Investigation 8 (2): 89–94. June 2011. doi:10.4306/pi.2011.8.2.89. PMID 21852983.

- ↑ "Sensory processing subtypes in autism: association with adaptive behavior". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 40 (1): 112–22. January 2010. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0840-2. PMID 19644746.

- ↑ "Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 61 (2): 190–200. 2007. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.190. PMID 17436841.

- ↑ "Sensory correlations in autism". Autism 11 (2): 123–34. March 2007. doi:10.1177/1362361307075702. PMID 17353213.

- ↑ Flanagan, Joanne (2009). "Sensory processing disorder". Pediatric News. Kennedy Krieger.org. http://www.kennedykrieger.org/sites/kki2.com/files/08-09.pdf.

- ↑ "Abnormal white matter microstructure in children with sensory processing disorders". NeuroImage. Clinical 2: 844–53. June 17, 2013. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2013.06.009. PMID 24179836.

- ↑ "Autism and sensory processing disorders: shared white matter disruption in sensory pathways but divergent connectivity in social-emotional pathways". PLOS ONE 9 (7). July 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103038. PMID 25075609. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j3038C.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Palmer, Brian (2014-02-28). "Get Ready for the Next Big Medical Fight Is sensory processing disorder a real disease?". http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/medical_examiner/2014/02/sensory_processing_disorder_the_debate_over_whether_spd_is_a_real_disease.html.

- ↑ "Sensory Processing Disorder". InfoSpace Holdings LLC. 2008-06-17. https://health.howstuffworks.com/pregnancy-and-parenting/childhood-conditions/sensory-processing-disorder1.htm.

- ↑ "The neural basis of multisensory integration in the midbrain: its organization and maturation". Hearing Research 258 (1–2): 4–15. December 2009. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2009.03.012. PMID 19345256.

- ↑ "Validating the diagnosis of sensory processing disorders using EEG technology". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 61 (2): 176–89. 2007. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.176. PMID 17436840.

- ↑ "A population-based twin study of parentally reported tactile and auditory defensiveness in young children". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 34 (3): 393–407. June 2006. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9024-0. PMID 16649001.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Marco, Elysa J.; Hinkley, Leighton B. N.; Hill, Susanna S.; Nagarajan, Srikantan S. (May 2011). "Sensory Processing in Autism: A Review of Neurophysiologic Findings" (in en). Pediatric Research 69 (8): 48–54. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182130c54. ISSN 1530-0447. PMID 21289533.

- ↑ "Maturation of sensory gating performance in children with and without sensory processing disorders". International Journal of Psychophysiology 72 (2): 187–97. May 2009. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.12.007. PMID 19146890.

- ↑ "Comparison of sensory gating to mismatch negativity and self-reported perceptual phenomena in healthy adults". Psychophysiology 41 (4): 604–12. July 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00191.x. PMID 15189483. http://spdfoundation.net/pdf/kisely_noecker.pdf.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "An exploratory event-related potential study of multisensory integration in sensory over-responsive children". Brain Research 1321: 67–77. March 2010. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.043. PMID 20097181. http://spdfoundation.net/pdf/Brett-Green_et_al%20article_2010.pdf.

- ↑ "Sensory processing disorder in a primate model: evidence from a longitudinal study of prenatal alcohol and prenatal stress effects". Child Development 79 (1): 100–13. 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01113.x. PMID 18269511. PMC 4226060. http://www.sinetwork.org/pdf/schneider_moore.pdf.

- ↑ "Abnormal white matter microstructure in children with sensory processing disorders". NeuroImage. Clinical 2: 844–53. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2013.06.009. PMID 24179836.

- ↑ "Autism and sensory processing disorders: shared white matter disruption in sensory pathways but divergent connectivity in social-emotional pathways". PLOS ONE 9 (7). 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103038. PMID 25075609. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j3038C.

- ↑ ICD 10

- ↑ Miller, Lucy Jane. "Final Decision for DSM-V". Sensory Processing Disorder Foundation. http://spdfoundation.net/sensory-processing-blog/2012/12/05/final-decision-for-dsm-v/.

- ↑ "Sensory Processing Disorder Test And ABA: What You Need To Know" (in en). 2023-11-01. https://www.levelaheadaba.com/sensory-processing-disorder-test-and-aba-what-you-need-to-know.

- ↑ "Course information and booking". Sensory Integration Network. http://www.sensoryintegration.org.uk/course-information-and-booking.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Assessments of sensory processing in infants: a systematic review". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 55 (4): 314–26. April 2013. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04434.x. PMID 23157488.

- ↑ "The sensory profile: a discriminant analysis of children with and without disabilities". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 52 (4): 283–90. April 1998. doi:10.5014/ajot.52.4.283. PMID 9544354.

- ↑ "Developmental Risk Signals as a Screening Tool for Early Identification of Sensory Processing Disorders". Occupational Therapy International 23 (2): 154–64. June 2016. doi:10.1002/oti.1420. PMID 26644234.

- ↑ "Development of the Sensory Processing Measure-School: initial studies of reliability and validity". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 61 (2): 170–5. 2007. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.170. PMID 17436839. http://ajot.aotapress.net/content/61/2/170.full.pdf.

- ↑ "The Sensory Processing Measure–Preschool (SPM-P)—Part One: Description of the Tool and Its Use in the Preschool Environment". Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention 4 (1): 42–52. 2011. doi:10.1080/19411243.2011.573245.

- ↑ Mulligan, Shelley (1998-11-01). "Patterns of Sensory Integration Dysfunction: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 52 (10): 819–828. doi:10.5014/ajot.52.10.819. ISSN 0272-9490.

- ↑ "Perspectives on sensory processing disorder: a call for translational research". Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 3: 22. 2009. doi:10.3389/neuro.07.022.2009. PMID 19826493.

- ↑ "Sensory integration therapies for children with developmental and behavioral disorders". Pediatrics 129 (6): 1186–9. June 2012. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0876. PMID 22641765.

- ↑ "Parasympathetic functions in children with sensory processing disorder". Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 4: 4. 2010. doi:10.3389/fnint.2010.00004. PMID 20300470.

- ↑ Miller, L. J., Reisman, J. E., McIntosh, D. N., & Simon, J. (2001). An ecological model of sensory modulation: Performance of children with fragile X syndrome, autistic disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and sensory modulation dysfunction. In S. S. Roley, E. I. Blanche, & R. C. Schaaf (Eds.), Understanding the nature of sensory integration with diverse populations, (pp. 57-88). Therapy Skill Builders. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304716933_An_ecological_model_of_sensory_integration_performance_of_children_with_fragile_X_syndrome_autistic_disorder_attention-deficithyperactivity_disorder_and_sensory_modulation_dysfunction

- ↑ "Development of multisensory reweighting is impaired for quiet stance control in children with developmental coordination disorder (DCD)". PLOS ONE 7 (7). 2012. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040932. PMID 22815872. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...740932B.

- ↑ Lonkar, Heather. "An overview of sensory processing disorder". Western Michigan University. http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3437&context=honors_theses.

- ↑ Bundy, Anita C; Lane, Shelly J; Murray, Elizabeth A (2002). Sensory integration: theory and practice (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. ISBN 978-0-8036-0545-9. OCLC 49421642.

- ↑ Watling, Renee; Bodison, Stefanie; Henry, Diana; Miller-Kuhaneck, Heather (2006-12-01). "Sensory Integration: It's Not Just for Children". Occupational Therapy Faculty Publications 29 (4). https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/ot_fac/17.

- ↑ Brown, Stephen; Shankar, Rohit; Smith, Kathryn (2009). "Borderline personality disorder and sensory processing impairment" (in en). Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry 13 (4): 10–16. doi:10.1002/pnp.127. ISSN 1931-227X.

- ↑ Brown, Catana (2002-09-14). "What Is the Best Environment for Me? A Sensory Processing Perspective". Occupational Therapy in Mental Health 17 (3–4): 115–125. doi:10.1300/j004v17n03_08. ISSN 0164-212X.

- ↑ "What is Sensory Processing Disorder? | Meaning | Symptoms | Causes" (in en). https://www.fluentaac.com/sensory-processing-disorder.

- ↑ Leong, H. M.; Carter, Mark; Stephenson, Jennifer (2015-12-01). "Systematic review of sensory integration therapy for individuals with disabilities: Single case design studies" (in en). Research in Developmental Disabilities 47: 334–351. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.09.022. ISSN 0891-4222. PMID 26476485. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0891422215001687.

- ↑ Section On Complementary And Integrative Medicine; Council on Children with Disabilities; Zimmer, M.; Desch, L. (2012). "AAP Login". Pediatrics 129 (6): 1186–1189. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0876. PMID 22641765. https://www.aap.org/en/my-account/login/. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- ↑ Hyatt, Keith J.; Stephenson, Jennifer; Carter, Mark (2009). "A Review of Three Controversial Educational Practices: Perceptual Motor Programs, Sensory Integration, and Tinted Lenses". Education and Treatment of Children 32 (2): 313–342. doi:10.1353/etc.0.0054. ISSN 0748-8491.

- ↑ Stephenson, Jennifer; Carter, Mark (2008-07-01). "The Use of Weighted Vests with Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Other Disabilities" (in en). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 39 (1): 105–114. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0605-3. ISSN 1573-3432. PMID 18592366.

- ↑ Schaaf, Roseann C.; Dumont, Rachel L.; Arbesman, Marian; May-Benson, Teresa A. (2017-12-13). "Efficacy of Occupational Therapy Using Ayres Sensory Integration®: A Systematic Review". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 72 (1): 7201190010p1–7201190010p10. doi:10.5014/ajot.2018.028431. ISSN 0272-9490. PMID 29280711.

- ↑ Watling, Renee; Hauer, Sarah (2015-09-04). "Effectiveness of Ayres Sensory Integration® and Sensory-Based Interventions for People With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 69 (5): 6905180030p1–6905180030p12. doi:10.5014/ajot.2015.018051. ISSN 0272-9490. PMID 26356655.

- ↑ "The "So What?" of Sensory Integration Therapy: Joie de Vivre". Sensory Solutions. Sensory Processing Disorder Foundation. 2013. http://spdfoundation.net/files/2714/2430/1254/Jan-Feb2013_sensorysolutions.pdf.

- ↑ Peske, Nancy; Biel, Lindsey (2005). Raising a sensory smart child: the definitive handbook for helping your child with sensory integration issues. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303488-9. OCLC 56420392. https://archive.org/details/raisingsensorysm00biel_0.

- ↑ "Sensory Checklist". Raising a Sensory Smart Child. http://sensorysmarts.com/sensory-checklist.pdf.

- ↑ "A systematic review of ayres sensory integration intervention for children with autism". Autism Research 12 (1): 6–19. January 2019. doi:10.1002/aur.2046. PMID 30548827.

- ↑ "®: A Systematic Review". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 72 (1): 7201190010p1–7201190010p10. 2018-01-01. doi:10.5014/ajot.2018.028431. PMID 29280711.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions About Ayres Sensory Integration". American Occupational Therapy Association. 2008. https://www.aota.org/-/media/Corporate/Files/Practice/Children/Resources/FAQs/SI%20Fact%20Sheet%202.pdf.

- ↑ "Sensory and Auditory Integration Therapy". http://www.aetna.com/cpb/medical/data/200_299/0256.html.

- ↑ "Sensory integration therapies for children with developmental and behavioral disorders". Pediatrics 129 (6): 1186–9. June 2012. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0876. PMID 22641765.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Smith, T., Mruzek, D. W., & Mozingo, D. (2015). Sensory integration therapy. In R. M. Foxx & J. A. Mulick (Eds.), Controversial therapies for autism (2nd ed.) (pp. 247-269). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315754345

- ↑ "Sensory over-responsivity in elementary school: prevalence and social-emotional correlates". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 37 (5): 705–16. July 2009. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9295-8. PMID 19153827. PMC 5972374. http://www.spdfoundation.net/pdf/Sensory_Over-Responsivity_in_Elementary_School_Prevalence_and_Social_Emotional_Correlates_2009.pdf.

- ↑ "Prevalence of parents' perceptions of sensory processing disorders among kindergarten children". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 58 (3): 287–93. 2004. doi:10.5014/ajot.58.3.287. PMID 15202626. http://spdnetwork.com/pdf/Prevalence-of-Parents-Perceptions-of-SPD-2004.pdf.

- ↑ "The Effectiveness of Sensory Integration Therapy to Improve Functional Behaviour in Adults with Learning Disabilities: Five Single-Case Experimental Designs". Br. J. Occup. Ther. 68 (2): 56–66. February 2005. doi:10.1177/030802260506800202.

- ↑ Brown, Stephen; Shankar, Rohit; Smith, Kathryn (2009). "Borderline personality disorder and sensory processing impairment". Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry 13 (4): 10–16. doi:10.1002/pnp.127.

- ↑ "Sensory Integration and Sensory- based Interventions". https://www.rcot.co.uk/about-occupational-therapy/rcot-informed-views.

- ↑ "Sensory Integration". https://www.aota.org/practice/children-youth/si.aspx.

- ↑ "Autism Diagnoses Shouldn't Be One-Size Fits All" (in en-US). 2020-01-15. https://www.fatherly.com/health-science/sensory-processing-disorder-autism/.

- ↑ Center for Autism and the Developing Brain

- ↑ Arky, Beth. "The debate over sensory processing". https://childmind.org/article/the-debate-over-sensory-processing/.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Wood, Jessica K. (2020-07-01). "Sensory Processing Disorder: Implications for Primary Care Nurse Practitioners" (in en). The Journal for Nurse Practitioners 16 (7): 514–516. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.03.022. ISSN 1555-4155. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1555415520301823.

- ↑ Association., American Psychiatric (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89042-556-5. OCLC 825047464.

- ↑ Ayres, A. Jean; Robbins, Jeff (2005). Sensory integration and the child: understanding hidden sensory challenge (25th Anniversary ed.). Los Angeles, CA: WPS. ISBN 978-0-87424-437-3. OCLC 63189804.

- ↑ Bundy, Anita. C.; Lane, J. Shelly; Murray, Elizabeth A. (2002). Sensory integration, Theory and practice. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company. ISBN 978-0-8036-0545-9.

- ↑ Mulligan, Shelley (1998). "Patterns of Sensory Integration Dysfunction: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis". American Journal of Occupational Therapy 52 (November/December): 819–828. doi:10.5014/ajot.52.10.819.

- ↑ "Understanding Ayres Sensory Integration". OT Practice. 17 12. September 2007. http://www.pediatrictherapy.com/images/content/208.pdf. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Dunn, Winnie (April 1997). "The Impact of Sensory Processing Abilities on the Daily Lives of Young Children and Their Families: A Conceptual Model". Infants & Young Children 9 (4): 23–35. doi:10.1097/00001163-199704000-00005. http://journals.lww.com/iycjournal/abstract/1997/04000/the_impact_of_sensory_processing_abilities_on_the.5.aspx. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ↑ "The sensations of everyday life: empirical, theoretical, and pragmatic considerations". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 55 (6): 608–20. 2001. doi:10.5014/ajot.55.6.608. PMID 12959225.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 88.3 "The relationship between sensory processing patterns and sleep quality in healthy adults". Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 79 (3): 134–41. June 2012. doi:10.2182/cjot.2012.79.3.2. PMID 22822690.

Template:Sensation and perception

|