Medicine:Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | |

|---|---|

| |

| People with ADHD may find focusing on and completing tasks such as schoolwork more difficult than others do. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, pediatrics |

| Symptoms | Difficulty paying attention, excessive activity, executive dysfunction, difficulty controlling behavior |

| Usual onset | Before age 6–12 |

| Causes | Both genetic and environmental factors |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after other possible causes ruled out |

| Differential diagnosis | Normally active young child, conduct disorder, autism spectrum disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, learning disorder, bipolar disorder, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder |

| Treatment | Psychotherapy, lifestyle changes, medications |

| Medication | Stimulants (i.e., methylphenidate, mixed amphetamine salts), atomoxetine, guanfacine, clonidine |

| Frequency | 84.7 million (2019) |

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a behavioral and neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, which are pervasive, impairing, and otherwise age inappropriate.[1][2] Some individuals with ADHD also display difficulty regulating emotions, or problems with executive function. For a diagnosis, the symptoms have to be present for more than six months, and cause problems in at least two settings (such as school, home, work, or recreational activities). In children, problems paying attention may result in poor school performance. Additionally, it is associated with other mental disorders and substance use disorders. Although it causes impairment, particularly in modern society, many people with ADHD have sustained attention for tasks they find interesting or rewarding, known as hyperfocus.

The precise cause or causes are unknown in the majority of cases.[3] Genetic factors are estimated to make up about 75% of the risk. Toxins and infections during pregnancy and brain damage may be environmental risks. It does not appear to be related to the style of parenting or discipline.[4] It affects about 5–7% of children when diagnosed via the DSM-IV criteria and 1–2% when diagnosed via the ICD-10 criteria. As of 2019, it was estimated to affect 84.7 million people globally.[5] Rates are similar between countries and differences in rates depend mostly on how it is diagnosed.[6] ADHD is diagnosed approximately two times more often in boys than in girls,[1] although the disorder is often overlooked in girls or only diagnosed in later life because their symptoms often differ from diagnostic criteria.[7][8][9][10] About 30–50% of people diagnosed in childhood continue to have symptoms into adulthood and between 2–5% of adults have the condition.[11][12] In adults, inner restlessness, rather than hyperactivity, may occur. Adults often develop coping skills which compensate for some or all of their impairments. The condition can be difficult to tell apart from other conditions, as well as from high levels of activity within the range of normal behavior.

ADHD management recommendations vary by country and usually involve some combination of medications, counseling, and lifestyle changes.[13] The British guideline emphasises environmental modifications and education for individuals and carers about ADHD as the first response. If symptoms persist, then parent-training, medication, or psychotherapy (especially cognitive behavioral therapy) can be recommended based on age.[14] Canadian and American guidelines recommend medications and behavioral therapy together, except in preschool-aged children for whom the first-line treatment is behavioral therapy alone.[15][16][17] For children and adolescents older than 5, treatment with stimulants is effective for at least 24 months;[18] however, for some, there may be potentially serious side effects.[19][20][21][22]

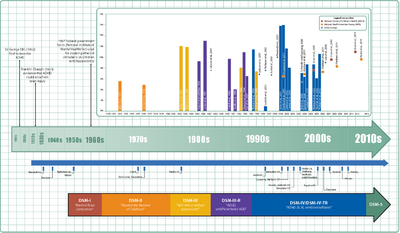

ADHD, its diagnosis, and its treatment have been considered controversial since the 1970s. The controversies have involved clinicians, teachers, policymakers, parents, and the media. Topics include ADHD's causes and the use of stimulant medications in its treatment. Most healthcare providers accept ADHD as a genuine diagnosis in children and adults, and the debate in the scientific community mainly centers on how it is diagnosed and treated.[23][24] The condition was officially known as attention deficit disorder (ADD) from 1980 to 1987, and prior to the 1980s, it was known as hyperkinetic reaction of childhood. The medical literature has described symptoms similar to those of ADHD since the 18th century.

Signs and symptoms

Inattention, hyperactivity (restlessness in adults), disruptive behavior, and impulsivity are common in ADHD.[25][26] Academic difficulties are frequent as are problems with relationships.[25] The symptoms can be difficult to define, as it is hard to draw a line at where normal levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity end and significant levels requiring interventions begin.[27]

According to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), symptoms must be present for six months or more to a degree that is much greater than others of the same age.[1] This requires at least 6 symptoms of either inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity for those under 17 and at least 5 for those 17 years or older.[1] The symptoms must interfere with or reduce quality of functioning in at least two settings (e.g., social, school, work, or home).[1] Additionally, several symptoms must have been present before age twelve.[1]

Subtypes

ADHD is divided into three primary presentations: predominantly inattentive (ADHD-PI or ADHD-I), predominantly hyperactive-impulsive (ADHD-PH or ADHD-HI), and combined type (ADHD-C).[1][27]

The table "DSM-5 symptoms" lists the symptoms for ADHD-I and ADHD-HI. Symptoms which can be better explained by another psychiatric or medical condition which an individual has are not considered to be a symptom of ADHD for that person.

| Presentations | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Inattentive | 6 or more of the following symptoms in children, and 5 or more in adults, excluding situations where these symptoms are better explained by another psychiatric or medical condition:

|

| Hyperactive-Impulsive | 6 or more of the following symptoms in children, and 5 or more in adults, excluding situations where these symptoms are better explained by another psychiatric or medical condition:

|

| Combined | Meet the criteria for both inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive ADHD. |

Girls and women with ADHD tend to display fewer hyperactivity and impulsivity symptoms but more symptoms of inattention and distractibility.[28] Symptoms of hyperactivity tend to go away with age and turn into inner restlessness in teens and adults with ADHD.[11] Although not listed as an official symptom for this condition, emotional dysregulation is generally understood to be a common symptom of ADHD.[29] Before this condition had the title of ADHD, emotional dysregulation was commonly listed as a symptom.[citation needed]

People with ADHD of all ages are more likely to have problems with social skills, such as social interaction and forming and maintaining friendships. This is true for all presentations. About half of children and adolescents with ADHD experience social rejection by their peers compared to 10–15% of non-ADHD children and adolescents. People with attention deficits are prone to having difficulty processing verbal and nonverbal language which can negatively affect social interaction. They also may drift off during conversations, miss social cues, and have trouble learning social skills.[30]

Difficulties managing anger are more common in children with ADHD[31] as are poor handwriting[32] and delays in speech, language and motor development.[33][34] Although it causes significant difficulty, many children with ADHD have an attention span equal to or greater than that of other children for tasks and subjects they find interesting.[35]

Comorbidities

Psychiatric

In children, ADHD occurs with other disorders about two-thirds of the time.[35]

Other neurodevelopmental conditions are common comorbidities. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) co-occurring at a rate of 21%, affects social skills, ability to communicate, behaviour, and interests.[36][37] As of 2013, the DSM-5 allows for an individual to be diagnosed with both ASD and ADHD.[1] Learning disabilities have been found to occur in about 20–30% of children with ADHD. Learning disabilities can include developmental speech and language disorders, and academic skills disorders.[38] ADHD, however, is not considered a learning disability, but it very frequently causes academic difficulties.[38] Intellectual disabilities[1] and Tourette's syndrome[37] are also common.

ADHD is often comorbid with disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) occurs in about 25% of children with an inattentive presentation and 50% of those with a combined presentation.[1] It is characterized by angry or irritable mood, argumentative or defiant behaviour and vindictiveness which are age-inappropriate. Conduct disorder (CD) occurs in about 25% of adolescents with ADHD.[1] It is characterized by aggression, destruction of property, deceitfulness, theft and violations of rules.[39] Adolescents with ADHD who also have CD are more likely to develop antisocial personality disorder in adulthood.[40] Brain imaging supports that CD and ADHD are separate conditions, wherein conduct disorder was shown to reduce the size one's temporal lobe and limbic system, and increase the size of one's orbitofrontal cortex whereas ADHD was shown to reduce connections in the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex more broadly. Conduct disorder involves more impairment in motivation control than ADHD.[41] Intermittent explosive disorder is characterized by sudden and disproportionate outbursts of anger, and commonly co-occurs with ADHD.[1]

Anxiety and mood disorders are frequent comorbidities. Anxiety disorders have been found to occur more commonly in the ADHD population.[42] This is also true of mood disorders (especially bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder). Boys diagnosed with the combined ADHD subtype are more likely to have a mood disorder.[42] Adults and children with ADHD sometimes also have bipolar disorder, which requires careful assessment to accurately diagnose and treat both conditions.[43][44]

Sleep disorders and ADHD commonly co-exist. They can also occur as a side effect of medications used to treat ADHD. In children with ADHD, insomnia is the most common sleep disorder with behavioral therapy the preferred treatment.[45][46] Problems with sleep initiation are common among individuals with ADHD but often they will be deep sleepers and have significant difficulty getting up in the morning.[47] Melatonin is sometimes used in children who have sleep onset insomnia.[48] Specifically, the sleep disorder restless legs syndrome has been found to be more common in those with ADHD and is often due to iron deficiency anemia.[49][50] However, restless legs can simply be a part of ADHD and requires careful assessment to differentiate between the two disorders.[51] People with ADHD also have an increased risk of persistent bed wetting.[52] Delayed sleep phase disorder is also quite a common comorbidity of those with ADHD.[53]

There are other psychiatric conditions which are often co-morbid with ADHD, such as substance use disorders. Individuals with ADHD are at increased risk of substance abuse.[11] This is most commonly seen with alcohol or cannabis.[11] The reason for this may be an altered reward pathway in the brains of ADHD individuals.[11] This makes the evaluation and treatment of ADHD more difficult, with serious substance misuse problems usually treated first due to their greater risks.[54] Other psychiatric conditions include reactive attachment disorder,[55] characterized by a severe inability to appropriately relate socially, and sluggish cognitive tempo, a cluster of symptoms that potentially comprises another attention disorder and may occur in 30–50% of ADHD cases, regardless of the subtype.[56]

Non-pyschiatric

Some non-psychiatric conditions are also comorbidities of ADHD. This includes epilepsy,[37] a neurological condition characterized by recurrent seizures. Further, a 2016 systematic review found a well established association between ADHD and obesity, asthma and sleep disorders, and tentative evidence for association with celiac disease and migraine,[57] while another 2016 systematic review did not support a clear link between celiac disease and ADHD, and stated that routine screening for celiac disease in people with ADHD is discouraged.[58]

Suicide risk

Systematic reviews conducted in 2017 and 2020 found strong evidence that ADHD is associated with increased suicide risk across all age groups, as well as growing evidence that an ADHD diagnosis in childhood or adolescence represents a significant future suicidal risk factor.[59][60] Potential causes include ADHD's association with functional impairment, negative social, educational and occupational outcomes, and financial distress.[61][62] A 2019 meta-analysis indicated a significant association between ADHD and suicidal spectrum behaviors (suicidal attempts, ideations, plans, and completed suicides); across the studies examined, the prevalence of suicide attempts in individuals with ADHD was 18.9%, compared to 9.3% in individuals without ADHD, and the findings were substantially replicated among studies which adjusted for other variables. However, the relationship between ADHD and suicidal spectrum behaviors remains unclear due to mixed findings across individual studies and the complicating impact of comorbid psychiatric disorders.[61] There is no clear data on whether there is a direct relationship between ADHD and suicidality, or whether ADHD increases suicide risk through comorbidities.[60]

IQ test performance

Certain studies have found that people with ADHD tend to have lower scores on intelligence quotient (IQ) tests.[63] The significance of this is controversial due to the differences between people with ADHD and the difficulty determining the influence of symptoms, such as distractibility, on lower scores rather than intellectual capacity.[63] In studies of ADHD, higher IQs may be over represented because many studies exclude individuals who have lower IQs despite those with ADHD scoring on average nine points lower on standardized intelligence measures.[64] In individuals with high intelligence, there is increased risk of a missed ADHD diagnosis, possibly because of compensatory strategies in highly intelligent individuals.[65]

Studies of adults suggest that negative differences in intelligence are not meaningful and may be explained by associated health problems.[66]

Causes

ADHD is generally claimed to be the result of neurological dysfunction in processes associated with the production or use of dopamine and norepinephrine in various brain structures, but there are no confirmed causes.[67][68] It may involve interactions between genetics and the environment.[67][68][69]

Genetics

Twin studies indicate that the disorder is often inherited from the person's parents, with genetics determining about 75% of cases in children and 35% to potentially 75% of cases in adults.[70] Siblings of children with ADHD are three to four times more likely to develop the disorder than siblings of children without the disorder.[71]

Arousal is related to dopaminergic functioning, and ADHD presents with low dopaminergic functioning.[72] Typically, a number of genes are involved, many of which directly affect dopamine neurotransmission.[73][74] Those involved with dopamine include DAT, DRD4, DRD5, TAAR1, MAOA, COMT, and DBH.[74][75][76] Other genes associated with ADHD include SERT, HTR1B, SNAP25, GRIN2A, ADRA2A, TPH2, and BDNF.[73][74] A common variant of a gene called latrophilin 3 is estimated to be responsible for about 9% of cases and when this variant is present, people are particularly responsive to stimulant medication.[77] The 7 repeat variant of dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4–7R) causes increased inhibitory effects induced by dopamine and is associated with ADHD. The DRD4 receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor that inhibits adenylyl cyclase. The DRD4–7R mutation results in a wide range of behavioral phenotypes, including ADHD symptoms reflecting split attention.[78] The DRD4 gene is both linked to novelty seeking and ADHD. People with Down syndrome are more likely to have ADHD.[79] The genes GFOD1 and CHD13 show strong genetic associations with ADHD. CHD13's association with ASD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression make it an interesting candidate causative gene.[80] Another candidate causative gene that has been identified is ADGRL3. In zebrafish, knockout of this gene causes a loss of dopaminergic function in the ventral diencephalon and the fish display a hyperactive/impulsive phenotype.[80]

For genetic variation to be used as a tool for diagnosis, more validating studies need to be performed. However, smaller studies have shown that genetic polymorphisms in genes related to catecholaminergic neurotransmission or the SNARE complex of the synapse can reliably predict a person's response to stimulant medication.[80] Rare genetic variants show more relevant clinical significance as their penetrance (the chance of developing the disorder) tends to be much higher.[81] However their usefulness as tools for diagnosis is limited as no single gene predicts ADHD. ASD shows genetic overlap with ADHD at both common and rare levels of genetic variation.[81]

Environment

In addition to genetics, some environmental factors might play a role in causing ADHD.[82][83] Alcohol intake during pregnancy can cause fetal alcohol spectrum disorders which can include ADHD or symptoms like it.[84] Children exposed to certain toxic substances, such as lead or polychlorinated biphenyls, may develop problems which resemble ADHD.[3][85] Exposure to the organophosphate insecticides chlorpyrifos and dialkyl phosphate is associated with an increased risk; however, the evidence is not conclusive.[86] Exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy can cause problems with central nervous system development and can increase the risk of ADHD.[3][87] Nicotine exposure during pregnancy may be an environmental risk.[88]

Extreme premature birth, very low birth weight, and extreme neglect, abuse, or social deprivation also increase the risk[3][89] as do certain infections during pregnancy, at birth, and in early childhood. These infections include, among others, various viruses (measles, varicella zoster encephalitis, rubella, enterovirus 71).[90] There is an association between long term but not short term use of acetaminophen during pregnancy and ADHD.[91][92] At least 30% of children with a traumatic brain injury later develop ADHD[93] and about 5% of cases are due to brain damage.[94]

Some studies suggest that in a small number of children, artificial food dyes or preservatives may be associated with an increased prevalence of ADHD or ADHD-like symptoms,[3][95] but the evidence is weak and may only apply to children with food sensitivities.[95][82][96] The United Kingdom and the European Union have put in place regulatory measures based on these concerns.[97] In a minority of children, intolerances or allergies to certain foods may worsen ADHD symptoms.[98]

Research does not support popular beliefs that ADHD is caused by eating too much refined sugar, watching too much television, parenting, poverty or family chaos; however, they might worsen ADHD symptoms in certain people.[26]

Society

The youngest children in a class have been found to be more likely to be diagnosed as having ADHD, possibly due to them being developmentally behind their older classmates.[99][100][101] This effect has been seen across a number of countries.[101] They also appear to use ADHD medications at nearly twice the rate of their peers.[102]

In some cases, an inappropriate diagnosis of ADHD may reflect a dysfunctional family or a poor educational system, rather than any true presence of ADHD in the individual.[103] In other cases, it may be explained by increasing academic expectations, with a diagnosis being a method for parents in some countries to get extra financial and educational support for their child.[94] Behaviors typical of ADHD occur more commonly in children who have experienced violence and emotional abuse.[19]

The social construct theory of ADHD suggests that because the boundaries between normal and abnormal behavior are socially constructed (i.e. jointly created and validated by all members of society, and in particular by physicians, parents, teachers, and others), it then follows that subjective valuations and judgements determine which diagnostic criteria are used and thus, the number of people affected.[104] This difference means using DSM-IV criteria could diagnose ADHD at rates three to four times higher than ICD-10 criteria.[10] Thomas Szasz, a supporter of this theory, has argued that ADHD was "invented and then given a name".[105]

Pathophysiology

Current models of ADHD suggest that it is associated with functional impairments in some of the brain's neurotransmitter systems, particularly those involving dopamine and norepinephrine.[106][107] The dopamine and norepinephrine pathways that originate in the ventral tegmental area and locus coeruleus project to diverse regions of the brain and govern a variety of cognitive processes.[106][108] The dopamine pathways and norepinephrine pathways which project to the prefrontal cortex and striatum are directly responsible for modulating executive function (cognitive control of behavior), motivation, reward perception, and motor function;[106][107][108] these pathways are known to play a central role in the pathophysiology of ADHD.[106][108][109][110] Larger models of ADHD with additional pathways have been proposed.[107][109][110]

Brain structure

In children with ADHD, there is a general reduction of volume in certain brain structures, with a proportionally greater decrease in the volume in the left-sided prefrontal cortex.[107][111] The posterior parietal cortex also shows thinning in individuals with ADHD compared to controls.[107] Other brain structures in the prefrontal-striatal-cerebellar and prefrontal-striatal-thalamic circuits have also been found to differ between people with and without ADHD.[107][109][110]

The subcortical volumes of the accumbens, amygdala, caudate, hippocampus, and putamen appears smaller in individuals with ADHD compared with controls.[112] Inter-hemispheric asymmetries in white matter tracts have also been noted in children with ADHD, suggesting that disruptions in temporal integration may be related to the behavioral characteristics of ADHD.[113]

Neurotransmitter pathways

Previously it was thought that the elevated number of dopamine receptors in people with ADHD was part of the pathophysiology but it appears that the elevated numbers are due to adaptation to exposure to stimulants.[114] Current models involve the mesocorticolimbic dopamine pathway and the locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system.[106][107][108] ADHD psychostimulants possess treatment efficacy because they increase neurotransmitter activity in these systems.[107][108][115] There may additionally be abnormalities in serotonergic, glutamatergic, or cholinergic pathways.[115][116][117]

Executive function and motivation

The symptoms of ADHD arise from a deficiency in certain executive functions (e.g., attentional control, inhibitory control, and working memory).[47][107][108][118] Executive functions are a set of cognitive processes that are required to successfully select and monitor behaviors that facilitate the attainment of one's chosen goals.[47][108][118] The executive function impairments that occur in ADHD individuals result in problems with staying organized, time keeping, excessive procrastination, maintaining concentration, paying attention, ignoring distractions, regulating emotions, and remembering details.[47][107][108] People with ADHD appear to have unimpaired long-term memory, and deficits in long-term recall appear to be attributed to impairments in working memory.[47][119] The criteria for an executive function deficit are met in 30–50% of children and adolescents with ADHD.[120] One study found that 80% of individuals with ADHD were impaired in at least one executive function task, compared to 50% for individuals without ADHD.[121] Due to the rates of brain maturation and the increasing demands for executive control as a person gets older, ADHD impairments may not fully manifest themselves until adolescence or even early adulthood.[47]

ADHD has also been associated with motivational deficits in children.[122] Children with ADHD often find it difficult to focus on long-term over short-term rewards, and exhibit impulsive behavior for short-term rewards.[122]

Paradoxical reactions to chemical substances

Additional signs of structurally altered signal processing in the central nervous system are the more frequently observed paradoxical reactions (ca. 10-20 % of Patients) in patients with ADHD. These are contrary (or otherwise deviating) reactions to what would usually be expected in a patient. Neuroactive substances which play a role include local anesthesia (used e. g. at a dental treatment), tranquilizers, caffeine, antihistamine, low-potency neuroleptic as well as central and peripheral pain killers. Since paradoxical reactions may partly have a genetic cause, it has been recommended to ask in a critical situation, like a surgery, if such reactions occurred in the patient or relatives.[123][124]

Diagnosis

ADHD is diagnosed by an assessment of a person's behavioral and mental development, including ruling out the effects of drugs, medications, and other medical or psychiatric problems as explanations for the symptoms.[54] ADHD diagnosis often takes into account feedback from parents and teachers[125] with most diagnoses begun after a teacher raises concerns.[94] It may be viewed as the extreme end of one or more continuous human traits found in all people.[126] Imaging studies of the brain do not give consistent results between individuals, they are only used for research purposes and not a diagnosis.[127]

In North America and Australia, DSM-5 criteria are used for diagnosis, while European countries usually use the ICD-10. The DSM-IV criteria for diagnosis of ADHD is 3–4 times more likely to diagnose ADHD than is the ICD-10 criteria.[10] ADHD is alternately classified as neurodevelopmental disorder[128][11] or a disruptive behavior disorder along with ODD, CD, and antisocial personality disorder.[129] A diagnosis does not imply a neurological disorder.[19]

Associated conditions that should be screened for include anxiety, depression, ODD, CD, and learning and language disorders. Other conditions that should be considered are other neurodevelopmental disorders, tics, and sleep apnea.[130]

Self-rating scales, such as the ADHD rating scale and the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic rating scale, are used in the screening and evaluation of ADHD.[131]

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

As with many other psychiatric disorders, a formal diagnosis should be made by a qualified professional based on a set number of criteria. In the United States, these criteria are defined by the American Psychiatric Association in the DSM. Based on the DSM-5 criteria published in 2013, there are three presentations of ADHD:[1]

- ADHD, predominantly inattentive type, presents with symptoms including being easily distracted, forgetful, daydreaming, disorganization, poor concentration, and difficulty completing tasks.[1]

- ADHD, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type, presents with excessive fidgeting and restlessness, hyperactivity, and difficulty waiting and remaining seated.[1]

- ADHD, combined type, is a combination of the first two presentations.[1]

This subdivision is based on presence of at least six out of nine long-term (lasting at least six months) symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity–impulsivity, or both.[1] To be considered, several symptoms must have appeared by the age of six to twelve and occur in more than one environment (e.g. at home and at school or work).[1] The symptoms must be inappropriate for a child of that age[1][132] and there must be clear evidence that they are causing social, school or work related problems.[133]

The DSM-5 also provides two diagnoses for individuals who have symptoms of ADHD but do not entirely meet the requirements. Other Specified ADHD allows the clinician to describe why the individual does not met the criteria, whereas Other Unspecified ADHD is used where the clinician chooses not to describe the reason.[1]

International Classification of Diseases

In the tenth revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) by the World Health Organization, the symptoms of hyperkinetic disorder were analogous to ADHD in the DSM-5. When a conduct disorder (as defined by ICD-10)[33] is present, the condition was referred to as hyperkinetic conduct disorder. Otherwise, the disorder was classified as disturbance of activity and attention, other hyperkinetic disorders or hyperkinetic disorders, unspecified. The latter was sometimes referred to as hyperkinetic syndrome.[33]

In the implementation version of ICD-11, the disorder is classified under 6A05 (Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), and hyperkinetic disorder no longer exists. The defined subtypes are similar to those of the DSM-5: predominantly inattentive presentation (6A05.0); predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentation(6A05.1); combined presentation (6A05.2). However, the ICD-11 includes two residual categories for individuals who do not entirely match any of the defined subtypes: other specified presentation (6A05.Y) where the clinician includes detail on the individual's presentation; and presentation unspecified (6A05.Z) where the clinician does not provide detail.[2]

Adults

Adults with ADHD are diagnosed under the same criteria, including that their signs must have been present by the age of six to twelve. Questioning parents or guardians as to how the person behaved and developed as a child may form part of the assessment; a family history of ADHD also adds weight to a diagnosis.[11] While the core symptoms of ADHD are similar in children and adults, they often present differently in adults than in children: for example, excessive physical activity seen in children may present as feelings of restlessness and constant mental activity in adults.[11]

It is estimated that 2–5% of adults have ADHD.[11] Around 25–50% of children with ADHD continue to experience ADHD symptoms into adulthood, while the rest experience fewer or no symptoms.[11][verification needed] Currently, most adults remain untreated.[134] Many adults with ADHD without diagnosis and treatment have a disorganized life, and some use non-prescribed drugs or alcohol as a coping mechanism.[135] Other problems may include relationship and job difficulties, and an increased risk of criminal activities.[11] Associated mental health problems include depression, anxiety disorders, and learning disabilities.[135]

Some ADHD symptoms in adults differ from those seen in children. While children with ADHD may climb and run about excessively, adults may experience an inability to relax, or may talk excessively in social situations. Adults with ADHD may start relationships impulsively, display sensation-seeking behavior, and be short-tempered. Addictive behavior such as substance abuse and gambling are common. The DSM-5 criteria do specifically deal with adults—unlike those in DSM-IV, which were criticized for not being appropriate for adults. This might lead to those who presented differently as they aged to having outgrown the DSM-IV criteria.[11]

For diagnosis in an adult, having symptoms since childhood is required. Nevertheless, a proportion of adults who meet the criteria for ADHD in adulthood would not have been diagnosed with ADHD as children. Most cases of late-onset ADHD develop the disorder between the ages of 12-16 and may therefore be considered early adult or adolescent-onset ADHD.[136]

Differential diagnosis

| Depression disorder | Anxiety disorder | Bipolar disorder |

|---|---|---|

|

The DSM provides potential differential diagnoses - potential alternate explanations for specific symptoms. Assessment and investigation of clinical history determines which is the most appropriate diagnosis. The DSM-5 suggests ODD, intermittent explosive disorder, other neurodevelopmental disorders (such as stereotypic movement disorder and Tourette's disorder), specific learning disorder, intellectual developmental disorder, ASD, reactive attachment disorder, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, substance use disorder, personality disorders, psychotic disorders, medication-induced symptoms, and dementia.[1] Many but not all of these are also common comorbidities of ADHD.[1]

Symptoms of ADHD, such as low mood and poor self-image, mood swings, and irritability, can be confused with dysthymia, cyclothymia or bipolar disorder as well as with borderline personality disorder.[11] Some symptoms that are due to anxiety disorders, antisocial personality disorder, developmental disabilities or mental retardation or the effects of substance abuse such as intoxication and withdrawal can overlap with some ADHD. These disorders can also sometimes occur along with ADHD. Medical conditions which can cause ADHD-type symptoms include: hyperthyroidism, seizure disorder, lead toxicity, hearing deficits, hepatic disease, sleep apnea, drug interactions, untreated celiac disease, and head injury.[135][58]

Primary sleep disorders may affect attention and behavior and the symptoms of ADHD may affect sleep.[137] It is thus recommended that children with ADHD be regularly assessed for sleep problems.[138] Sleepiness in children may result in symptoms ranging from the classic ones of yawning and rubbing the eyes, to hyperactivity and inattentiveness.[139] Obstructive sleep apnea can also cause ADHD-type symptoms.[139] Rare tumors called pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas may cause similar symptoms to ADHD.[140]

Management

The management of ADHD typically involves counseling or medications, either alone or in combination. While treatment may improve long-term outcomes, it does not get rid of negative outcomes entirely.[141] Medications used include stimulants, atomoxetine, alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists, and sometimes antidepressants.[42][115] In those who have trouble focusing on long-term rewards, a large amount of positive reinforcement improves task performance.[122] ADHD stimulants also improve persistence and task performance in children with ADHD.[107][122]

Behavioral therapies

There is good evidence for the use of behavioral therapies in ADHD. They are the recommended first-line treatment in those who have mild symptoms or who are preschool-aged.[142][143] Psychological therapies used include: psychoeducational input, behavior therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy,[144] interpersonal psychotherapy, family therapy, school-based interventions, social skills training, behavioral peer intervention, organization training,[145] and parent management training.[19] Neurofeedback has been used,[146] but it is unclear whether it is useful.[147] Parent training may improve a number of behavioral problems including oppositional and non-compliant behaviors.[148]

There is little high-quality research on the effectiveness of family therapy for ADHD—but the existing evidence shows that it is similar to community care, and better than placebo.[149] ADHD-specific support groups can provide information and may help families cope with ADHD.[150]

Social skills training, behavioral modification, and medication may have some limited beneficial effects in peer relationships. The most important factor in reducing later psychological problems—such as major depression, criminality, school failure, and substance use disorders—is formation of friendships with non-deviant peers.[151]

Medication

Stimulant medications are the most effective pharmaceutical treatment.[22] They improve symptoms in 80% of people, although improvement is not sustained if medication is ceased.[21][152][153] Methylphenidate appears to improve symptoms as reported by teachers and parents.[21][152][154] Stimulants may also reduce the risk of unintentional injuries in children with ADHD.[155] Magnetic resonance imaging studies suggest that long-term treatment with amphetamine or methylphenidate decreases abnormalities in brain structure and function found in subjects with ADHD.[156][157][158] A 2018 review found the greatest short-term benefit with methylphenidate in children, and amphetamines in adults.[159]

The long-term effects of ADHD medication have yet to be fully determined,[160][161] although stimulants are generally beneficial and safe for up to two years.[18] However, there are side-effects and contraindications to their use.[22] Stimulant psychosis and mania are very rare at therapeutic doses, appearing to occur in approximately 0.1% of individuals, within the first several weeks after starting amphetamine therapy.[162][163][164] Chronic heavy abuse of stimulants over months or years can trigger these symptoms, although administration of an antipsychotic medication has been found to effectively resolve the symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis.[162]

Regular monitoring has been recommended in those on long-term treatment.[165] There are indications suggesting that stimulant therapy for children and adolescents should be stopped periodically to assess continuing need for medication, decrease possible growth delay, and reduce tolerance.[166][167] Long-term misuse of stimulant medications at doses above the therapeutic range for ADHD treatment is associated with addiction and dependence.[168][169] Untreated ADHD, however, is also associated with elevated risk of substance use disorders and conduct disorders.[168] The use of stimulants appears to either reduce these risks or have no effect on it.[11][160][168] The negative consequences of untreated ADHD has led some guidelines to conclude that the dangers of not treating severe ADHD are greater than the potential risks of medication, regardless of age.[14] The safety of these medications in pregnancy is unclear.[170]

There are a number of non-stimulant medications, such as Viloxazine, atomoxetine, bupropion, guanfacine, and clonidine, that may be used as alternatives, or added to stimulant therapy.[22][171] There are no good studies comparing the various medications; however, they appear more or less equal with respect to side effects.[172] For children, stimulants appear to improve academic performance while atomoxetine does not.[173] Atomoxetine, due to its lack of addiction liability, may be preferred in those who are at risk of recreational or compulsive stimulant use.[11] Evidence supports its ability to improve symptoms when compared to placebo.[174] There is little evidence on the effects of medication on social behaviors.[172] Antipsychotics may also be used to treat aggression in ADHD.[175]

Guidelines on when to use medications vary by country. The United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends use for children only in severe cases, though for adults medication is a first-line treatment.[14] Conversely, most United States guidelines recommend medications in most age groups.[15] Medications are especially not recommended for preschool children.[14][19] Underdosing of stimulants can occur, and can result in a lack of response or later loss of effectiveness.[176] This is particularly common in adolescents and adults as approved dosing is based on school-aged children, causing some practitioners to use weight-based or benefit-based off-label dosing instead.[177][178][179]

Other

Regular physical exercise, particularly aerobic exercise, is an effective add-on treatment for ADHD in children and adults, particularly when combined with stimulant medication (although the best intensity and type of aerobic exercise for improving symptoms are not currently known).[180][181][182] In particular, the long-term effects of regular aerobic exercise in ADHD individuals include better behavior and motor abilities, improved executive functions (including attention, inhibitory control, and planning, among other cognitive domains), faster information processing speed, and better memory.[180][181][182] Parent-teacher ratings of behavioral and socio-emotional outcomes in response to regular aerobic exercise include: better overall function, reduced ADHD symptoms, better self-esteem, reduced levels of anxiety and depression, fewer somatic complaints, better academic and classroom behavior, and improved social behavior.[180] Exercising while on stimulant medication augments the effect of stimulant medication on executive function.[180] It is believed that these short-term effects of exercise are mediated by an increased abundance of synaptic dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain.[180]

Dietary modifications are not recommended as of 2019 by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality due to insufficient evidence.[17][14][18] A 2013 meta-analysis found less than a third of children with ADHD see some improvement in symptoms with free fatty acid supplementation or decreased eating of artificial food coloring.[82] These benefits may be limited to children with food sensitivities or those who are simultaneously being treated with ADHD medications.[82] This review also found that evidence does not support removing other foods from the diet to treat ADHD.[82] Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid supplementation was found by a 2018 review to not improve ADHD outcomes.[18] A 2014 review found that an elimination diet results in a small overall benefit in a minority of children, such as those with allergies.[98] A 2016 review stated that the use of a gluten-free diet as standard ADHD treatment is not advised.[58] A 2017 review showed that a few-foods elimination diet may help children too young to be medicated or not responding to medication, while free fatty acid supplementation or decreased eating of artificial food coloring as standard ADHD treatment is not advised.[183] Chronic deficiencies of iron, magnesium and iodine may have a negative impact on ADHD symptoms.[184] There is a small amount of evidence that lower tissue zinc levels may be associated with ADHD.[185] In the absence of a demonstrated zinc deficiency (which is rare outside of developing countries), zinc supplementation is not recommended as treatment for ADHD.[186] However, zinc supplementation may reduce the minimum effective dose of amphetamine when it is used with amphetamine for the treatment of ADHD.[187]

Prognosis

ADHD persists into adulthood in about 30–50% of cases.[188] Those affected are likely to develop coping mechanisms as they mature, thus compensating to some extent for their previous symptoms.[135] Children with ADHD have a higher risk of unintentional injuries.[155] One study from Denmark found an increased risk of death among those with ADHD due to the increased rate of accidents.[189] Effects of medication on functional impairment and quality of life (e.g. reduced risk of accidents) have been found across multiple domains.[190] Rates of smoking among those with ADHD are higher than in the general population at about 40%.[191]

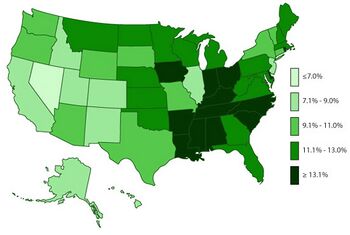

Epidemiology

ADHD is estimated to affect about 6–7% of people aged 18 and under when diagnosed via the DSM-IV criteria.[193] When diagnosed via the ICD-10 criteria, rates in this age group are estimated around 1–2%.[194] Children in North America appear to have a higher rate of ADHD than children in Africa and the Middle East; this is believed to be due to differing methods of diagnosis rather than a difference in underlying frequency.[195][verification needed] If the same diagnostic methods are used, the rates are similar between countries.[6] ADHD is diagnosed approximately three times more often in boys than in girls.[9][10] This may reflect either a true difference in underlying rate, or that women and girls with ADHD are less likely to be diagnosed.[196]

Rates of diagnosis and treatment have increased in both the United Kingdom and the United States since the 1970s.[197] Prior to 1970, it was rare for children to be diagnosed with ADHD while in the 1970s rates were about 1%.[198] This is believed to be primarily due to changes in how the condition is diagnosed[197] and how readily people are willing to treat it with medications rather than a true change in how common the condition is.[194] It is believed that changes to the diagnostic criteria in 2013 with the release of the DSM-5 will increase the percentage of people diagnosed with ADHD, especially among adults.[199]

Due to disparities in the treatment and understanding of ADHD between caucasian and non-caucasian populations, many non-caucasian children go undiagnosed and unmedicated.[200] It was found that within the US that there was often a disparity between caucasian and non-caucasian understandings of ADHD.[201] This led to a difference in the classification of the symptoms of ADHD, and therefore, its misdiagnosis.[201] It was also found that it was common in non-caucasian families and teachers to understand the symptoms of ADHD as behavioural issues, rather than mental illness.[201]

Crosscultural differences in diagnosis of ADHD can also be attributed to the long lasting effects of harmful, racially targeted medical practices. Medical pseudosciences, particularly those that targeted African American populations during the period of slavery in the US, lead to a distrust of medical practices within certain communities.[201] The combination of ADHD symptoms often being regarded as misbehaviour rather than as a psychiatric condition, and the use of drugs to regulate ADHD, result in a hesitancy to trust a diagnosis of ADHD. Cases of misdiagnosis in ADHD can also occur due to stereotyping of non-caucasian individuals.[201] Due to ADHD's subjectively determined symptoms, medical professionals may diagnose individuals based on stereotyped behaviour or misdiagnose due to differences in symptom presentation between Caucasian and non-Caucasian individuals.[201]

History

Hyperactivity has long been part of the human condition. Sir Alexander Crichton describes "mental restlessness" in his book An inquiry into the nature and origin of mental derangement written in 1798.[202][203][page needed] He made observations about children showing signs of being inattentive and having the "fidgets". The first clear description of ADHD is credited to George Still in 1902 during a series of lectures he gave to the Royal College of Physicians of London.[204][197] He noted both nature and nurture could be influencing this disorder.[205]

Alfred Tredgold proposed an association between brain damage and behavioral or learning problems which was able to be validated by the encephalitis lethargica epidemic from 1917 through 1928.[205][206][207]

The terminology used to describe the condition has changed over time and has included: minimal brain dysfunction in the DSM-I (1952), hyperkinetic reaction of childhood in the DSM-II (1968), and attention-deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity in the DSM-III (1980).[197] In 1987, this was changed to ADHD in the DSM-III-R, and in 1994 the DSM-IV in split the diagnosis into three subtypes: ADHD inattentive type, ADHD hyperactive-impulsive type, and ADHD combined type.[208] These terms were kept in the DSM-5 in 2013.[1] Prior to the DSM, terms included minimal brain damage in the 1930s.[209]

In 1934, Benzedrine became the first amphetamine medication approved for use in the United States.[210] Methylphenidate was introduced in the 1950s, and enantiopure dextroamphetamine in the 1970s.[197] The use of stimulants to treat ADHD was first described in 1937.[211] Charles Bradley gave the children with behavioral disorders Benzedrine and found it improved academic performance and behavior.[212][213]

Until the 1990s, many studies "implicated the prefrontal-striatal network as being smaller in children with ADHD".[214][quantify] During this same period,[when?] a genetic component was identified and ADHD was acknowledged to be a persistent, long-term disorder which lasted from childhood into adulthood.[215] ADHD was split into the current three sub-types because of a field trial completed by Lahey and colleagues.[1][216]

Controversy

ADHD, its diagnosis, and its treatment have been controversial since the 1970s.[217][152][218] The controversies involve clinicians, teachers, policymakers, parents, and the media. Positions range from the view that ADHD is within the normal range of behavior[54][219] to the hypothesis that ADHD is a genetic condition.[220] Other areas of controversy include the use of stimulant medications in children,[152][221] the method of diagnosis, and the possibility of overdiagnosis.[221] In 2009, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, while acknowledging the controversy, states that the current treatments and methods of diagnosis are based on the dominant view of the academic literature.[126] In 2014, Keith Conners, one of the early advocates for recognition of the disorder, spoke out against overdiagnosis in a The New York Times article.[222] In contrast, a 2014 peer-reviewed medical literature review indicated that ADHD is under diagnosed in adults.[12]

With widely differing rates of diagnosis across countries, states within countries, races, and ethnicities, some suspect factors other than the presence of the symptoms of ADHD are playing a role in diagnosis.[223] Some sociologists consider ADHD to be an example of the medicalization of deviant behavior, that is, the turning of the previously non-medical issue of school performance into a medical one.[217][94] Most healthcare providers accept ADHD as a genuine disorder, at least in the small number of people with severe symptoms.[94] Among healthcare providers the debate mainly centers on diagnosis and treatment in the much greater number of people with mild symptoms.[23][24][94][222][224][225][excessive citations]

Research directions

Research into positive traits

Possible positive traits of ADHD are a new avenue of research, and therefore limited.[226] Studies are being done on whether ADHD symptoms could potentially be beneficial.

A 2020 review found that creativity may be associated with ADHD symptoms, particularly divergent thinking and quantity of creative achievements, but not with the disorder of ADHD itself – i.e. it has not been found in patients diagnosed with the disorder, only in patients with subclinical symptoms or those that possess traits associated with the disorder.[226] Divergent thinking is the ability to produce creative solutions which differ significantly from each other and consider the issue from multiple perspectives.[226] Those with ADHD symptoms could be advantaged in this form of creativity as they tend to have diffuse attention, allowing rapid switching between aspects of the task under consideration;[226] flexible associative memory, allowing them to remember and use more distantly-related ideas which is associated with creativity; and impulsivity, which causes people with ADHD symptoms to consider ideas which others may not have.[226] However, people with ADHD may struggle with convergent thinking, which is a process of creativity that requires sustained effort and consistent use of executive functions to weed out solutions which aren't creative from a single area of inquiry.[226] People with the actual disorder often struggle with executive functioning.[227]

In entrepreneurship, there has been interest in the traits of people with ADHD.[228][229] This is due in part to a number of high-profile entrepreneurs having traits that could be associated with ADHD.[230] Some people with ADHD are interested in entrepreneurship, and have some traits which could be considered useful to entrepreneurial skills: curiosity, openness to experience, impulsivity, risk-taking, and hyperfocus.[229]

Research into use of biomarkers for diagnosis

Reviews of ADHD biomarkers have noted that platelet monoamine oxidase expression, urinary norepinephrine, urinary MHPG, and urinary phenethylamine levels consistently differ between ADHD individuals and healthy controls.[231] These measurements could potentially serve as diagnostic biomarkers for ADHD, but more research is needed to establish their diagnostic utility.[231] Urinary and blood plasma phenethylamine concentrations are lower in ADHD individuals relative to controls and the two most commonly prescribed drugs for ADHD, amphetamine and methylphenidate, increase phenethylamine biosynthesis in treatment-responsive individuals with ADHD.[232][231] Lower urinary phenethylamine concentrations are also associated with symptoms of inattentiveness in ADHD individuals.[231] Electroencephalography is not accurate enough to make an ADHD diagnosis.[233]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 59–65. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "ICD-11 – 6A05 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f821852937.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 NIMH (2013). "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (Easy-to-Read)". National Institute of Mental Health. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-easy-to-read/index.shtml.

- ↑ "Does Bad Parenting Cause ADHD?". https://www.webmd.com/add-adhd/childhood-adhd/parenting-role-in-adhd#1.

- ↑ Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (17 October 2020). "Global Burden of Disease Study 2019: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—Level 3 cause". The Lancet 396 (10258). https://www.thelancet.com/pb-assets/Lancet/gbd/summaries/diseases/adhd.pdf.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Ch. 25: Epidemiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". Textbook of Psychiatric Epidemiology (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. 2011. pp. 450. ISBN 9780470977408. https://books.google.com/books?id=fOc4pdXe43EC&pg=PA450.

- ↑ Young, Susan; Adamo, Nicoletta; Ásgeirsdóttir, Bryndís Björk; Branney, Polly; Beckett, Michelle; Colley, William; Cubbin, Sally; Deeley, Quinton et al. (December 2020). "Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in girls and women" (in en). BMC Psychiatry 20 (1): 404. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02707-9. ISSN 1471-244X. PMID 32787804.

- ↑ Crawford, Nicole (February 2003). "ADHD: a women's issue". Monitor on Psychology 34 (2): 28. http://www.apa.org/monitor/feb03/adhd.aspx.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "[Structural and functional neuroanatomy of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)]" (in FR). L'Encephale 35 (2): 107–14. April 2009. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2008.01.005. PMID 19393378.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "Beyond polemics: science and ethics of ADHD". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 9 (12): 957–64. December 2008. doi:10.1038/nrn2514. PMID 19020513.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 "European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD". BMC Psychiatry 10: 67. September 2010. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-10-67. PMID 20815868.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Underdiagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adult patients: a review of the literature". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders 16 (3). 2014. doi:10.4088/PCC.13r01600. PMID 25317367. "Reports indicate that ADHD affects 2.5%–5% of adults in the general population,5–8 compared with 5%–7% of children.9,10 ... However, fewer than 20% of adults with ADHD are currently diagnosed and/or treated by psychiatrists.7,15,16".

- ↑ "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". March 2016. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/index.shtml.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2019). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. NICE Guideline, No. 87. London: National Guideline Centre (UK). ISBN 978-1-4731-2830-9. OCLC 1126668845. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87/.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines". Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance. http://www.caddra.ca/cms4/pdfs/caddraGuidelines2011Introduction.pdf.

- ↑ "Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Recommendations". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 24 June 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/guidelines.html.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Wolraich, ML; Hagan JF, Jr; Allan, C; Chan, E; Davison, D; Earls, M; Evans, SW; Flinn, SK et al. (October 2019). "Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents.". Pediatrics 144 (4): e20192528. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-2528. PMID 31570648.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Kemper, Alex R.; Maslow, Gary R.; Hill, Sherika; Namdari, Behrouz; Allen LaPointe, Nancy M.; Goode, Adam P.; Coeytaux, Remy R.; Befus, Deanna et al. (2018-01-25). "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Treatment in Children and Adolescents" (in en). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. doi:10.23970/ahrqepccer203.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2009). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and Adults. NICE Clinical Guidelines. 72. Leicester: British Psychological Society. ISBN 978-1-85433-471-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53652/.

- ↑ "Effect of treatment modality on long-term outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review". PLOS ONE 10 (2): e0116407. February 2015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116407. PMID 25714373. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1016407A.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 "The long-term outcomes of interventions for the management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Psychology Research and Behavior Management 6: 87–99. September 2013. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S49114. PMID 24082796. "Results suggest there is moderate-to-high-level evidence that combined pharmacological and behavioral interventions, and pharmacological interventions alone can be effective in managing the core ADHD symptoms and academic performance at 14 months. However, the effect size may decrease beyond this period. ... Only one paper examining outcomes beyond 36 months met the review criteria. ... There is high level evidence suggesting that pharmacological treatment can have a major beneficial effect on the core symptoms of ADHD (hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity) in approximately 80% of cases compared with placebo controls, in the short term.22".

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 "Efficacy and safety limitations of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder pharmacotherapy in children and adults". CNS Drugs 23 Suppl 1: 21–31. 2009. doi:10.2165/00023210-200923000-00004. PMID 19621975.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (3rd ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. 2004. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-1-58562-131-6.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: complexities and controversies". Current Opinion in Pediatrics 18 (2): 189–95. April 2006. doi:10.1097/01.mop.0000193302.70882.70. PMID 16601502.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Diagnosis and management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in primary care for school-age children and adolescents". 2012. pp. 79. http://guidelines.gov/content.aspx?f=rss&id=36812.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 CDC (6 January 2016), Facts About ADHD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html, retrieved 20 March 2016

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Cognitive behavioral therapy for adult ADHD. Routledge. 2007. pp. 4, 25–26. ISBN 978-0-415-95501-0.

- ↑ "A meta-analytic review of gender differences in ADHD". Journal of Attention Disorders 5 (3): 143–54. January 2002. doi:10.1177/108705470200500302. PMID 11911007.

- ↑ "Emotional dysregulation in adult ADHD: What is the empirical evidence?". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 12 (10): 1241–51. October 2012. doi:10.1586/ern.12.109. PMID 23082740.

- ↑ "Social competence and friendship formation in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Adolescent Medicine 19 (2): 278–99, x. August 2008. PMID 18822833.

- ↑ "ADHD Anger Management Directory". Webmd.com. http://www.webmd.com/add-adhd/adhd-anger-management-directory.

- ↑ "Handwriting performance in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". Journal of Child Neurology 23 (4): 399–406. April 2008. doi:10.1177/0883073807309244. PMID 18401033.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 "F90 Hyperkinetic disorders", International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision, World Health Organisation, 2010, http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en#/F90, retrieved 2 November 2014

- ↑ "Language disturbances in ADHD". Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 20 (4): 311–5. December 2011. doi:10.1017/S2045796011000527. PMID 22201208.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "[The school child with ADHD"] (in DE). Therapeutische Umschau 69 (8): 467–73. August 2012. doi:10.1024/0040-5930/a000316. PMID 22851461. https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/74507/1/Schulkind_mit_ADHS_Final_Manuskript.pdf.

- ↑ Young, Susan; Hollingdale, Jack; Absoud, Michael; Bolton, Patrick; Branney, Polly; Colley, William; Craze, Emily; Dave, Mayuri et al. (2020-05-25). "Guidance for identification and treatment of individuals with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder based upon expert consensus". BMC medicine (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 18 (1). doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01585-y. ISSN 1741-7015. PMID 32448170.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 "ADHD Symptoms". 20 October 2017. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/symptoms/#related-conditions-in-children-and-teenagers.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Bailey, Eileen. "ADHD and Learning Disabilities: How can you help your child cope with ADHD and subsequent Learning Difficulties? There is a way.". Remedy Health Media, LLC.. http://www.healthcentral.com/adhd/education-159625-5.html.

- ↑ "Evaluation and diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children". Uptodate. Wolters Kluwer Health. 5 December 2007. http://www.uptodate.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=behavior/8293#5.

- ↑ "Continuity of aggressive antisocial behavior from childhood to adulthood: The question of phenotype definition". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 32 (4): 224–34. 2009. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.04.004. PMID 19428109. http://lup.lub.lu.se/search/ws/files/5190474/1430656.pdf.

- ↑ ""Cool" inferior frontostriatal dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder versus "hot" ventromedial orbitofrontal-limbic dysfunction in conduct disorder: a review". Biological Psychiatry 69 (12): e69-87. June 2011. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.023. PMID 21094938.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 "Understanding attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from childhood to adulthood". Postgraduate Medicine 122 (5): 97–109. September 2010. doi:10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2206. PMID 20861593.

- ↑ "[Bipolar disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: differential diagnosis or comorbidity]" (in fr). Revue Médicale Suisse 7 (297): 1219–22. June 2011. PMID 21717696.

- ↑ "The intersection of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse". Current Opinion in Psychiatry 24 (4): 280–5. July 2011. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328345c956. PMID 21483267.

- ↑ "A framework for the assessment and treatment of sleep problems in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Pediatric Clinics of North America 58 (3): 667–83. June 2011. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.004. PMID 21600348.

- ↑ "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sleep disorders in children". The Medical Clinics of North America 94 (3): 615–32. May 2010. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2010.03.008. PMID 20451036.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 47.5 "ADD/ADHD and Impaired Executive Function in Clinical Practice". Current Psychiatry Reports 10 (5): 407–11. October 2008. doi:10.1007/s11920-008-0065-7. PMID 18803914.

- ↑ "Melatonin treatment for insomnia in pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 44 (1): 185–91. January 2010. doi:10.1345/aph.1M365. PMID 20028959.

- ↑ "[Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and restless legs syndrome in children]" (in es). Revista de Neurología 52 Suppl 1: S85-95. March 2011. PMID 21365608.

- ↑ "Advances in pediatric restless legs syndrome: Iron, genetics, diagnosis and treatment". Sleep Medicine 11 (7): 643–51. August 2010. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2009.11.014. PMID 20620105.

- ↑ "[Restless-legs syndrome]" (in fr). Revue Neurologique 164 (8–9): 701–21. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2008.06.006. PMID 18656214.

- ↑ "Prevalence of enuresis and its association with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among U.S. children: results from a nationally representative study". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 48 (1): 35–41. January 2009. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e318190045c. PMID 19096296.

- ↑ Wajszilber, Dafna; Santisteban, José Arturo; Gruber, Reut (December 2018). "Sleep disorders in patients with ADHD: impact and management challenges" (in en). Nature and Science of Sleep 10: 453–480. doi:10.2147/NSS.S163074. ISSN 1179-1608. PMID 30588139. PMC 6299464. https://www.dovepress.com/sleep-disorders-in-patients-with-adhd-impact-and-management-challenges-peer-reviewed-article-NSS.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2009). "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and Adults. NICE Clinical Guidelines. 72. Leicester: British Psychological Society. pp. 18–26, 38. ISBN 978-1-85433-471-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53663/.

- ↑ Storebø, Ole Jakob; Rasmussen, Pernille Darling; Simonsen, Erik (2016-02-01). "Association Between Insecure Attachment and ADHD: Environmental Mediating Factors" (in en). Journal of Attention Disorders 20 (2): 187–196. doi:10.1177/1087054713501079. ISSN 1087-0547. PMID 24062279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713501079.

- ↑ 2014.pdf "Sluggish cognitive tempo (concentration deficit disorder?): current status, future directions, and a plea to change the name". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 42 (1): 117–25. January 2014. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9824-y. PMID 24234590. https://psychology.uiowa.edu/sites/psychology.uiowa.edu/files/groups/nikolas/files/Barkley, 2014.pdf.

- ↑ "Adult ADHD and Comorbid Somatic Disease: A Systematic Literature Review". Journal of Attention Disorders 22 (3): 203–228. February 2018. doi:10.1177/1087054716669589. PMID 27664125.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 "Association of ADHD and Celiac Disease: What Is the Evidence? A Systematic Review of the Literature". Journal of Attention Disorders 24 (10): 1371–1376. January 2016. doi:10.1177/1087054715611493. PMID 26825336. "Up till now, there is no conclusive evidence for a relationship between ADHD and CD. Therefore, it is not advised to perform routine screening of CD when assessing ADHD (and vice versa) or to implement GFD as a standard treatment in ADHD. Nevertheless, the possibility of untreated CD predisposing to ADHD-like behavior should be kept in mind. ... It is possible that in untreated patients with CD, neurologic symptoms such as chronic fatigue, inattention, pain, and headache could predispose patients to ADHD-like behavior (mainly symptoms of inattentive type), which may be alleviated after GFD treatment. (CD: celiac disease; GFD: gluten-free diet)".

- ↑ Balazs, Judit; Kereszteny, Agnes (2017). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and suicide: A systematic review". World Journal of Psychiatry 7 (1): 44–59. doi:10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.44. PMID 28401048.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Garas, Peter; Balazs, Judit (21 December 2020). "Long-Term Suicide Risk of Children and Adolescents With Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder—A Systematic Review". Frontiers in Psychiatry 11: 15–17. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.557909. 557909. PMID 33408650.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Septier, Mathilde; Stordeur, Coline; Zhang, Junhua; Delorme, Richard; Cortese, Samuele (August 2019). "Association between suicidal spectrum behaviors and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 103: 109–118. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.05.022. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 31129238. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/431399/1/Septier_et_al_ADHD_SUICIDE_R2_CLEANED.docx.

- ↑ Beauchaine, Theodore P.; Ben-David, Itzhak; Bos, Marieke (September 2020). "ADHD, financial distress, and suicide in adulthood: A population study". Science Advances 6 (40): eaba1551. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba1551. eaba1551. PMID 32998893. Bibcode: 2020SciA....6.1551B.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 "Meta-analysis of intellectual and neuropsychological test performance in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Neuropsychology 18 (3): 543–55. July 2004. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.18.3.543. PMID 15291732.

- ↑ "Rethinking Intelligence Quotient Exclusion Criteria Practices in the Study of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". Frontiers in Psychology 7: 794. 2016. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00794. PMID 27303350.

- ↑ "An evidenced-based perspective on the validity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the context of high intelligence". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 71: 21–47. December 2016. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.032. PMID 27590827.

- ↑ "Intellectual functioning in adults with ADHD: a meta-analytic examination of full scale IQ differences between adults with and without ADHD". Psychological Assessment 18 (1): 1–14. March 2006. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.1. PMID 16594807.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Millichap, J. Gordon (2010). "Chapter 2: Causative Factors". Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer Science. pp. 26. doi:10.1007/978-104419-1397-5. ISBN 978-1-4419-1396-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=KAlq0CDcbaoC&pg=PA26.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "What have we learnt about the causes of ADHD?". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 54 (1): 3–16. January 2013. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02611.x. PMID 22963644.

- ↑ Scerif, Gaia; Baker, Kate (2015). "Annual Research Review: Rare genotypes and childhood psychopathology - uncovering diverse developmental mechanisms of ADHD risk". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 56 (3): 251–273. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12374. PMID 25494546.

- ↑ Brikell, Isabell; Kuja-Halkola, Ralf; Larsson, Henrik (2015-06-30). "Heritability of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 168 (6): 406–413. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.32335. ISSN 1552-4841. PMID 26129777.

- ↑ Abnormal Psychology (Sixth ed.). 2013. pp. 267. ISBN 978-0-07-803538-8.

- ↑ Hinshaw, Stephen P. (2018-05-07). "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Controversy, Developmental Mechanisms, and Multiple Levels of Analysis". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 14 (1): 291–316. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084917. ISSN 1548-5943. PMID 29220204.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Gizer, Ian R.; Ficks, Courtney; Waldman, Irwin D. (2009-06-09). "Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review". Human Genetics 126 (1): 51–90. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0694-x. ISSN 0340-6717. PMID 19506906.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 Kebir, Oussama; Joober, Ridha (2011-03-16). "Neuropsychological endophenotypes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review of genetic association studies". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 261 (8): 583–594. doi:10.1007/s00406-011-0207-5. ISSN 0940-1334. PMID 21409419.

- ↑ Berry, M. (2007-01-01). "The Potential of Trace Amines and Their Receptors for Treating Neurological and Psychiatric Diseases". Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials 2 (1): 3–19. doi:10.2174/157488707779318107. ISSN 1574-8871. PMID 18473983.

- ↑ Sotnikova, Tatyana D.; Caron, Marc G.; Gainetdinov, Raul R. (2009-04-23). "Trace Amine-Associated Receptors as Emerging Therapeutic Targets: TABLE 1". Molecular Pharmacology 76 (2): 229–235. doi:10.1124/mol.109.055970. ISSN 0026-895X. PMID 19389919.

- ↑ Arcos-Burgos, Mauricio; Muenke, Maximilian (2010-10-16). "Toward a better understanding of ADHD: LPHN3 gene variants and the susceptibility to develop ADHD". ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders 2 (3): 139–147. doi:10.1007/s12402-010-0030-2. ISSN 1866-6116. PMID 21432600.

- ↑ Nikolaidis, Aki; Gray, Jeremy R. (2009-12-17). "ADHD and the DRD4 exon III 7-repeat polymorphism: an international meta-analysis". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 5 (2–3): 188–193. doi:10.1093/scan/nsp049. ISSN 1749-5024. PMID 20019071.

- ↑ Ekstein, Sivan; Glick, Benjamin; Weill, Michal; Kay, Barrie; Berger, Itai (2011-05-31). "Down Syndrome and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)". Journal of Child Neurology 26 (10): 1290–1295. doi:10.1177/0883073811405201. ISSN 0883-0738. PMID 21628698.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 Grimm, Oliver; Kranz, Thorsten M.; Reif, Andreas (2020-02-27). "Genetics of ADHD: What Should the Clinician Know?". Current Psychiatry Reports 22 (4): 18. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-1141-x. ISSN 1523-3812. PMID 32108282.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Zayats, Tetyana; Neale, Benjamin M (2020-02-12). "Recent advances in understanding of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): how genetics are shaping our conceptualization of this disorder". F1000Research 8: 2060. doi:10.12688/f1000research.18959.2. ISSN 2046-1402. PMID 31824658.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 "Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments". The American Journal of Psychiatry 170 (3): 275–89. March 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070991. PMID 23360949. "Free fatty acid supplementation and artificial food color exclusions appear to have beneficial effects on ADHD symptoms, although the effect of the former are small and those of the latter may be limited to ADHD patients with food sensitivities...".

- ↑ CDC (16 March 2016), Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/research.html, retrieved 17 April 2016

- ↑ "[How does maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy affect the development of attention deficit/hyperactivity syndrome in the child]" (in de). Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie 79 (9): 500–6. September 2011. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1273360. PMID 21739408.

- ↑ "Lead and PCBs as risk factors for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Environmental Health Perspectives 118 (12): 1654–67. December 2010. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901852. PMID 20829149.

- ↑ "Does perinatal exposure to endocrine disruptors induce autism spectrum and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders? Review". Acta Paediatrica 101 (8): 811–8. August 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02693.x. PMID 22458970.

- ↑ "Smoking during pregnancy: lessons learned from epidemiological studies and experimental studies using animal models". Critical Reviews in Toxicology 42 (4): 279–303. April 2012. doi:10.3109/10408444.2012.658506. PMID 22394313.

- ↑ Tiesler, Carla M. T.; Heinrich, Joachim (21 September 2014). "Prenatal nicotine exposure and child behavioural problems". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 23 (10): 913–929. doi:10.1007/s00787-014-0615-y. PMID 25241028.

- ↑ "What causes attention deficit hyperactivity disorder?". Archives of Disease in Childhood 97 (3): 260–5. March 2012. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2011-300482. PMID 21903599.

- ↑ "Etiologic classification of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Pediatrics 121 (2): e358-65. February 2008. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1332. PMID 18245408.

- ↑ "Prenatal Exposure to Acetaminophen and Risk of ADHD". Pediatrics 140 (5): e20163840. November 2017. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3840. PMID 29084830.

- ↑ "An Association Between Prenatal Acetaminophen Use and ADHD: The Benefits of Large Data Sets". Pediatrics 140 (5): e20172703. November 2017. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2703. PMID 29084834.

- ↑ "ADHD: an integration with pediatric traumatic brain injury". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 12 (4): 475–83. April 2012. doi:10.1586/ern.12.15. PMID 22449218.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 94.2 94.3 94.4 94.5 Medicating Children: ADHD and Pediatric Mental Health (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. 2009. pp. 4–24. ISBN 978-0-674-03163-0.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 "The diet factor in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Pediatrics 129 (2): 330–7. February 2012. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2199. PMID 22232312. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/129/2/330.long.

- ↑ Tomaska, Luba D.; Brooke-Taylor, S. (2014). "Food Additives – General". in Motarjemi, Yasmine; Moy, Gerald G.; Todd, Ewen C.D.. Encyclopedia of Food Safety. 3 (1st ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 449–54. ISBN 978-0-12-378613-5. OCLC 865335120.

- ↑ FDA (March 2011), Background Document for the Food Advisory Committee: Certified Color Additives in Food and Possible Association with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/FoodAdvisoryCommittee/UCM248549.pdf