Monodromy

In mathematics, monodromy is the study of how objects from mathematical analysis, algebraic topology, algebraic geometry and differential geometry behave as they "run round" a singularity. As the name implies, the fundamental meaning of monodromy comes from "running round singly". It is closely associated with covering maps and their degeneration into ramification; the aspect giving rise to monodromy phenomena is that certain functions we may wish to define fail to be single-valued as we "run round" a path encircling a singularity. The failure of monodromy can be measured by defining a monodromy group: a group of transformations acting on the data that encodes what happens as we "run round" in one dimension. Lack of monodromy is sometimes called polydromy.[1]

Definition

Let X be a connected and locally connected based topological space with base point x, and let be a covering with fiber . For a loop γ: [0, 1] → X based at x, denote a lift under the covering map, starting at a point , by . Finally, we denote by the endpoint , which is generally different from . There are theorems which state that this construction gives a well-defined group action of the fundamental group π1(X, x) on F, and that the stabilizer of is exactly , that is, an element [γ] fixes a point in F if and only if it is represented by the image of a loop in based at . This action is called the monodromy action and the corresponding homomorphism π1(X, x) → Aut(H*(Fx)) into the automorphism group on F is the algebraic monodromy. The image of this homomorphism is the monodromy group. There is another map π1(X, x) → Diff(Fx)/Is(Fx) whose image is called the topological monodromy group.

Example

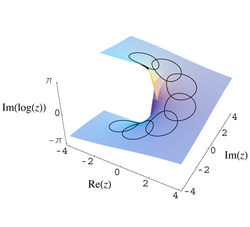

These ideas were first made explicit in complex analysis. In the process of analytic continuation, a function that is an analytic function F(z) in some open subset E of the punctured complex plane may be continued back into E, but with different values. For example, take

then analytic continuation anti-clockwise round the circle

will result in the return, not to F(z) but

In this case the monodromy group is infinite cyclic and the covering space is the universal cover of the punctured complex plane. This cover can be visualized as the helicoid (as defined in the helicoid article) restricted to ρ > 0. The covering map is a vertical projection, in a sense collapsing the spiral in the obvious way to get a punctured plane.

Differential equations in the complex domain

One important application is to differential equations, where a single solution may give further linearly independent solutions by analytic continuation. Linear differential equations defined in an open, connected set S in the complex plane have a monodromy group, which (more precisely) is a linear representation of the fundamental group of S, summarising all the analytic continuations round loops within S. The inverse problem, of constructing the equation (with regular singularities), given a representation, is called the Riemann–Hilbert problem.

For a regular (and in particular Fuchsian) linear system one usually chooses as generators of the monodromy group the operators Mj corresponding to loops each of which circumvents just one of the poles of the system counterclockwise. If the indices j are chosen in such a way that they increase from 1 to p + 1 when one circumvents the base point clockwise, then the only relation between the generators is the equality . The Deligne–Simpson problem is the following realisation problem: For which tuples of conjugacy classes in GL(n, C) do there exist irreducible tuples of matrices Mj from these classes satisfying the above relation? The problem has been formulated by Pierre Deligne and Carlos Simpson was the first to obtain results towards its resolution. An additive version of the problem about residua of Fuchsian systems has been formulated and explored by Vladimir Kostov. The problem has been considered by other authors for matrix groups other than GL(n, C) as well.[2]

Topological and geometric aspects

In the case of a covering map, we look at it as a special case of a fibration, and use the homotopy lifting property to "follow" paths on the base space X (we assume it path-connected for simplicity) as they are lifted up into the cover C. If we follow round a loop based at x in X, which we lift to start at c above x, we'll end at some c* again above x; it is quite possible that c ≠ c*, and to code this one considers the action of the fundamental group π1(X, x) as a permutation group on the set of all c, as a monodromy group in this context.

In differential geometry, an analogous role is played by parallel transport. In a principal bundle B over a smooth manifold M, a connection allows "horizontal" movement from fibers above m in M to adjacent ones. The effect when applied to loops based at m is to define a holonomy group of translations of the fiber at m; if the structure group of B is G, it is a subgroup of G that measures the deviation of B from the product bundle M × G.

Monodromy groupoid and foliations

Analogous to the fundamental groupoid it is possible to get rid of the choice of a base point and to define a monodromy groupoid. Here we consider (homotopy classes of) lifts of paths in the base space X of a fibration . The result has the structure of a groupoid over the base space X. The advantage is that we can drop the condition of connectedness of X.

Moreover the construction can also be generalized to foliations: Consider a (possibly singular) foliation of M. Then for every path in a leaf of we can consider its induced diffeomorphism on local transversal sections through the endpoints. Within a simply connected chart this diffeomorphism becomes unique and especially canonical between different transversal sections if we go over to the germ of the diffeomorphism around the endpoints. In this way it also becomes independent of the path (between fixed endpoints) within a simply connected chart and is therefore invariant under homotopy.

Definition via Galois theory

Let F(x) denote the field of the rational functions in the variable x over the field F, which is the field of fractions of the polynomial ring F[x]. An element y = f(x) of F(x) determines a finite field extension [F(x) : F(y)].

This extension is generally not Galois but has Galois closure L(f). The associated Galois group of the extension [L(f) : F(y)] is called the monodromy group of f.

In the case of F = C Riemann surface theory enters and allows for the geometric interpretation given above. In the case that the extension [C(x) : C(y)] is already Galois, the associated monodromy group is sometimes called a group of deck transformations.

This has connections with the Galois theory of covering spaces leading to the Riemann existence theorem.

See also

- Braid group

- Monodromy theorem

- Mapping class group (of a punctured disk)

Notes

- ↑ König, Wolfgang; Sprekels, Jürgen (2015) (in de). Karl Weierstraß (1815–1897): Aspekte seines Lebens und Werkes – Aspects of his Life and Work. Springer-Verlag. pp. 200–201. ISBN 9783658106195. https://books.google.com/books?id=7IHDCgAAQBAJ&q=Karl+Weierstra%C3%9F+(1815%E2%80%931897). Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ V. P. Kostov (2004), "The Deligne–Simpson problem — a survey", J. Algebra 281 (1): 83–108, doi:10.1016/j.jalgebra.2004.07.013 and the references therein.

References

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Monodromy", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=M/m064700

- "Group-groupoids and monodromy groupoids", O. Mucuk, B. Kılıçarslan, T. ¸Sahan, N. Alemdar, Topology and its Applications 158 (2011) 2034–2042 doi:10.1016/j.topol.2011.06.048

- R. Brown Topology and Groupoids (2006).

- P.J. Higgins, "Categories and groupoids", van Nostrand (1971) TAC Reprint

- H. Żołądek, "The Monodromy Group", Birkhäuser Basel 2006; doi: 10.1007/3-7643-7536-1

|