Physics:Second quantization

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

| History |

Second quantization, also referred to as occupation number representation, is a formalism used to describe and analyze quantum many-body systems. In quantum field theory, it is known as canonical quantization, in which the fields (typically as the wave functions of matter) are thought of as field operators, in a manner similar to how the physical quantities (position, momentum, etc.) are thought of as operators in first quantization. The key ideas of this method were introduced in 1927 by Paul Dirac,[1] and were later developed, most notably, by Pascual Jordan[2] and Vladimir Fock.[3][4] In this approach, the quantum many-body states are represented in the Fock state basis, which are constructed by filling up each single-particle state with a certain number of identical particles.[5] The second quantization formalism introduces the creation and annihilation operators to construct and handle the Fock states, providing useful tools to the study of the quantum many-body theory.

Quantum many-body states

The starting point of the second quantization formalism is the notion of indistinguishability of particles in quantum mechanics. Unlike in classical mechanics, where each particle is labeled by a distinct position vector and different configurations of the set of s correspond to different many-body states, in quantum mechanics, the particles are identical, such that exchanging two particles, i.e. , does not lead to a different many-body quantum state. This implies that the quantum many-body wave function must be invariant (up to a phase factor) under the exchange of two particles. According to the statistics of the particles, the many-body wave function can either be symmetric or antisymmetric under the particle exchange:

- if the particles are bosons,

- if the particles are fermions.

This exchange symmetry property imposes a constraint on the many-body wave function. Each time a particle is added or removed from the many-body system, the wave function must be properly symmetrized or anti-symmetrized to satisfy the symmetry constraint. In the first quantization formalism, this constraint is guaranteed by representing the wave function as linear combination of permanents (for bosons) or determinants (for fermions) of single-particle states. In the second quantization formalism, the issue of symmetrization is automatically taken care of by the creation and annihilation operators, such that its notation can be much simpler.

First-quantized many-body wave function

Consider a complete set of single-particle wave functions labeled by (which may be a combined index of a number of quantum numbers). The following wave function

represents an N-particle state with the ith particle occupying the single-particle state . In the shorthanded notation, the position argument of the wave function may be omitted, and it is assumed that the ith single-particle wave function describes the state of the ith particle. The wave function has not been symmetrized or anti-symmetrized, thus in general not qualified as a many-body wave function for identical particles. However, it can be brought to the symmetrized (anti-symmetrized) form by operators for symmetrizer, and for antisymmetrizer.

For bosons, the many-body wave function must be symmetrized,

while for fermions, the many-body wave function must be anti-symmetrized,

Here is an element in the N-body permutation group (or symmetric group) , which performs a permutation among the state labels , and denotes the corresponding permutation sign. is the normalization operator that normalizes the wave function. (It is the operator that applies a suitable numerical normalization factor to the symmetrized tensors of degree n; see the next section for its value.)

If one arranges the single-particle wave functions in a matrix , such that the row-i column-j matrix element is , then the boson many-body wave function can be simply written as a permanent , and the fermion many-body wave function as a determinant (also known as the Slater determinant).[6]

Second-quantized Fock states

First quantized wave functions involve complicated symmetrization procedures to describe physically realizable many-body states because the language of first quantization is redundant for indistinguishable particles. In the first quantization language, the many-body state is described by answering a series of questions like "Which particle is in which state?". However these are not physical questions, because the particles are identical, and it is impossible to tell which particle is which in the first place. The seemingly different states and are actually redundant names of the same quantum many-body state. So the symmetrization (or anti-symmetrization) must be introduced to eliminate this redundancy in the first quantization description.

In the second quantization language, instead of asking "each particle on which state", one asks "How many particles are there in each state?". Because this description does not refer to the labeling of particles, it contains no redundant information, and hence leads to a precise and simpler description of the quantum many-body state. In this approach, the many-body state is represented in the occupation number basis, and the basis state is labeled by the set of occupation numbers, denoted

meaning that there are particles in the single-particle state (or as ). The occupation numbers sum to the total number of particles, i.e. . For fermions, the occupation number can only be 0 or 1, due to the Pauli exclusion principle; while for bosons it can be any non-negative integer

The occupation number states are also known as Fock states. All the Fock states form a complete basis of the many-body Hilbert space, or Fock space. Any generic quantum many-body state can be expressed as a linear combination of Fock states.

Note that besides providing a more efficient language, Fock space allows for a variable number of particles. As a Hilbert space, it is isomorphic to the sum of the n-particle bosonic or fermionic tensor spaces described in the previous section, including a one-dimensional zero-particle space C.

The Fock state with all occupation numbers equal to zero is called the vacuum state, denoted . The Fock state with only one non-zero occupation number is a single-mode Fock state, denoted . In terms of the first quantized wave function, the vacuum state is the unit tensor product and can be denoted . The single-particle state is reduced to its wave function . Other single-mode many-body (boson) states are just the tensor product of the wave function of that mode, such as and . For multi-mode Fock states (meaning more than one single-particle state is involved), the corresponding first-quantized wave function will require proper symmetrization according to the particle statistics, e.g. for a boson state, and for a fermion state (the symbol between and is omitted for simplicity). In general, the normalization is found to be , where N is the total number of particles. For fermion, this expression reduces to as can only be either zero or one. So the first-quantized wave function corresponding to the Fock state reads

for bosons and

for fermions. Note that for fermions, only, so the tensor product above is effectively just a product over all occupied single-particle states.

Creation and annihilation operators

The creation and annihilation operators are introduced to add or remove a particle from the many-body system. These operators lie at the core of the second quantization formalism, bridging the gap between the first- and the second-quantized states. Applying the creation (annihilation) operator to a first-quantized many-body wave function will insert (delete) a single-particle state from the wave function in a symmetrized way depending on the particle statistics. On the other hand, all the second-quantized Fock states can be constructed by applying the creation operators to the vacuum state repeatedly.

The creation and annihilation operators (for bosons) are originally constructed in the context of the quantum harmonic oscillator as the raising and lowering operators, which are then generalized to the field operators in the quantum field theory.[7] They are fundamental to the quantum many-body theory, in the sense that every many-body operator (including the Hamiltonian of the many-body system and all the physical observables) can be expressed in terms of them.

Insertion and deletion operation

The creation and annihilation of a particle is implemented by the insertion and deletion of the single-particle state from the first quantized wave function in an either symmetric or anti-symmetric manner. Let be a single-particle state, let 1 be the tensor identity (it is the generator of the zero-particle space C and satisfies in the tensor algebra over the fundamental Hilbert space), and let be a generic tensor product state. The insertion and the deletion operators are linear operators defined by the following recursive equations

Here is the Kronecker delta symbol, which gives 1 if , and 0 otherwise. The subscript of the insertion or deletion operators indicates whether symmetrization (for bosons) or anti-symmetrization (for fermions) is implemented.

Boson creation and annihilation operators

The boson creation (resp. annihilation) operator is usually denoted as (resp. ). The creation operator adds a boson to the single-particle state , and the annihilation operator removes a boson from the single-particle state . The creation and annihilation operators are Hermitian conjugate to each other, but neither of them are Hermitian operators ().

Definition

The boson creation (annihilation) operator is a linear operator, whose action on a N-particle first-quantized wave function is defined as

where inserts the single-particle state in possible insertion positions symmetrically, and deletes the single-particle state from possible deletion positions symmetrically.

Examples

Hereinafter the tensor symbol between single-particle states is omitted for simplicity. Take the state , create one more boson on the state ,

Then annihilate one boson from the state ,

Action on Fock states

Starting from the single-mode vacuum state , applying the creation operator repeatedly, one finds

The creation operator raises the boson occupation number by 1. Therefore, all the occupation number states can be constructed by the boson creation operator from the vacuum state

On the other hand, the annihilation operator lowers the boson occupation number by 1

It will also quench the vacuum state as there has been no boson left in the vacuum state to be annihilated. Using the above formulae, it can be shown that

meaning that defines the boson number operator.

The above result can be generalized to any Fock state of bosons.

These two equations can be considered as the defining properties of boson creation and annihilation operators in the second-quantization formalism. The complicated symmetrization of the underlying first-quantized wave function is automatically taken care of by the creation and annihilation operators (when acting on the first-quantized wave function), so that the complexity is not revealed on the second-quantized level, and the second-quantization formulae are simple and neat.

Operator identities

The following operator identities follow from the action of the boson creation and annihilation operators on the Fock state,

These commutation relations can be considered as the algebraic definition of the boson creation and annihilation operators. The fact that the boson many-body wave function is symmetric under particle exchange is also manifested by the commutation of the boson operators.

The raising and lowering operators of the quantum harmonic oscillator also satisfy the same set of commutation relations, implying that the bosons can be interpreted as the energy quanta (phonons) of an oscillator. The position and momentum operators of a Harmonic oscillator (or a collection of Harmonic oscillating modes) are given by Hermitian combinations of phonon creation and annihilation operators,

which reproduce the canonical commutation relation between position and momentum operators (with )

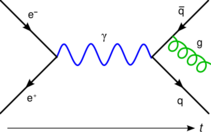

This idea is generalized in the quantum field theory, which considers each mode of the matter field as an oscillator subject to quantum fluctuations, and the bosons are treated as the excitations (or energy quanta) of the field.

Fermion creation and annihilation operators

The fermion creation (annihilation) operator is usually denoted as (). The creation operator adds a fermion to the single-particle state , and the annihilation operator removes a fermion from the single-particle state .

Definition

The fermion creation (annihilation) operator is a linear operator, whose action on a N-particle first-quantized wave function is defined as

where inserts the single-particle state in possible insertion positions anti-symmetrically, and deletes the single-particle state from possible deletion positions anti-symmetrically.

It is particularly instructive to view the results of creation and annihilation operators on states of two (or more) fermions, because they demonstrate the effects of exchange. A few illustrative operations are given in the example below. The complete algebra for creation and annihilation operators on a two-fermion state can be found in Quantum Photonics.[8]

Examples

Hereinafter the tensor symbol between single-particle states is omitted for simplicity. Take the state , attempt to create one more fermion on the occupied state will quench the whole many-body wave function,

Annihilate a fermion on the state, take the state ,

The minus sign (known as the fermion sign) appears due to the anti-symmetric property of the fermion wave function.

Action on Fock states

Starting from the single-mode vacuum state , applying the fermion creation operator ,

If the single-particle state is empty, the creation operator will fill the state with a fermion. However, if the state is already occupied by a fermion, further application of the creation operator will quench the state, demonstrating the Pauli exclusion principle that two identical fermions can not occupy the same state simultaneously. Nevertheless, the fermion can be removed from the occupied state by the fermion annihilation operator ,

The vacuum state is quenched by the action of the annihilation operator.

Similar to the boson case, the fermion Fock state can be constructed from the vacuum state using the fermion creation operator

It is easy to check (by enumeration) that

meaning that defines the fermion number operator.

The above result can be generalized to any Fock state of fermions.

Recall that the occupation number can only take 0 or 1 for fermions. These two equations can be considered as the defining properties of fermion creation and annihilation operators in the second quantization formalism. Note that the fermion sign structure , also known as the Jordan-Wigner string, requires there to exist a predefined ordering of the single-particle states (the spin structure)[clarification needed] and involves a counting of the fermion occupation numbers of all the preceding states; therefore the fermion creation and annihilation operators are considered non-local in some sense. This observation leads to the idea that fermions are emergent particles in the long-range entangled local qubit system.[10]

Operator identities

The following operator identities follow from the action of the fermion creation and annihilation operators on the Fock state,

These anti-commutation relations can be considered as the algebraic definition of the fermion creation and annihilation operators. The fact that the fermion many-body wave function is anti-symmetric under particle exchange is also manifested by the anti-commutation of the fermion operators.

The creation and annihilation operators are Hermitian conjugate to each other, but neither of them are Hermitian operators (). The Hermitian combination of the fermion creation and annihilation operators

are called Majorana fermion operators. They can be viewed as the fermionic analog of position and momentum operators of a "fermionic" Harmonic oscillator. They satisfy the anticommutation relation

where labels any Majorana fermion operators on equal footing (regardless their origin from Re or Im combination of complex fermion operators ). The anticommutation relation indicates that Majorana fermion operators generates a Clifford algebra, which can be systematically represented as Pauli operators in the many-body Hilbert space.

Quantum field operators

Defining as a general annihilation (creation) operator for a single-particle state that could be either fermionic or bosonic , the real space representation of the operators defines the quantum field operators and by

These are second quantization operators, with coefficients and that are ordinary first-quantization wavefunctions. Thus, for example, any expectation values will be ordinary first-quantization wavefunctions. Loosely speaking, is the sum of all possible ways to add a particle to the system at position r through any of the basis states , not necessarily plane waves, as below.

Since and are second quantization operators defined in every point in space they are called quantum field operators. They obey the following fundamental commutator and anti-commutator relations,

- boson fields,

- fermion fields.

For homogeneous systems it is often desirable to transform between real space and the momentum representations, hence, the quantum fields operators in Fourier basis yields:

Comment on nomenclature

The term "second quantization", introduced by Jordan,[11] is a misnomer that has persisted for historical reasons. At the origin of quantum field theory, it was inappositely thought that the Dirac equation described a relativistic wavefunction (hence the obsolete "Dirac sea" interpretation), rather than a classical spinor field which, when quantized (like the scalar field), yielded a fermionic quantum field (vs. a bosonic quantum field).

One is not quantizing "again", as the term "second" might suggest; the field that is being quantized is not a Schrödinger wave function that was produced as the result of quantizing a particle, but is a classical field (such as the electromagnetic field or Dirac spinor field), essentially an assembly of coupled oscillators, that was not previously quantized. One is merely quantizing each oscillator in this assembly, shifting from a semiclassical treatment of the system to a fully quantum-mechanical one.

See also

- Canonical quantization

- First quantization

- Geometric quantization

- Quantization

- Schrödinger functional

- Scalar field theory

References

- ↑ Dirac, Paul Adrien Maurice (1927). "The quantum theory of the emission and absorption of radiation". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character 114 (767): 243–265. doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0039. Bibcode: 1927RSPSA.114..243D.

- ↑ Jordan, Pascual; Wigner, Eugene (1928). "Über das Paulische Äquivalenzverbot" (in de). Zeitschrift für Physik 47 (9): 631–651. doi:10.1007/bf01331938. Bibcode: 1928ZPhy...47..631J.

- ↑ Fock, Vladimir Aleksandrovich (1932). "Konfigurationsraum und zweite Quantelung" (in de). Zeitschrift für Physik 75 (9–10): 622–647. doi:10.1007/bf01344458. Bibcode: 1932ZPhy...75..622F.

- ↑ Reed, Michael; Simon, Barry (1975). Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics. Volume II: Fourier Analysis, Self-Adjointness. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 328. ISBN 9780080925370.

- ↑ Becchi, Carlo Maria (2010). "Second quantization". Scholarpedia 5 (6): 7902. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.7902. Bibcode: 2010SchpJ...5.7902B.

- ↑ Koch, Erik (2013). "Many-electron states". in Pavarini, Eva. Emergent Phenomena in Correlated Matter. Modeling and Simulation. 3. Jülich: Verlag des Forschungszentrum Jülich. pp. 2.1–2.26. ISBN 978-3-89336-884-6. http://hdl.handle.net/2128/5389.

- ↑ Mahan, Gerald D. (2000). Many-Particle Physics. Physics of Solids and Liquids (3rd ed.). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-5714-9. ISBN 978-1-4757-5714-9.

- ↑ Pearsall, Thomas P. (2020). Quantum Photonics. Graduate Texts in Physics (2nd ed.). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. pp. 301–302. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-47325-9. ISBN 978-3-030-47325-9. Bibcode: 2020quph.book.....P.

- ↑ Book "Nuclear Models" of Greiner and Maruhn p53 equation 3.47 : http://xn--webducation-dbb.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Walter-Greiner-Joachim-A.-Maruhn-D.A.-Bromley-Nuclear-Models-Springer-Verlag-1996.pdf

- ↑ Levin, M.; Wen, X. G. (2003). "Fermions, strings, and gauge fields in lattice spin models". Physical Review B 67 (24): 245316. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.67.245316. Bibcode: 2003PhRvB..67x5316L.

- ↑ Todorov, Ivan (2012). "Quantization is a mystery". Bulgarian Journal of Physics 39 (2): 107–149.

|