Physics:Synchrotron

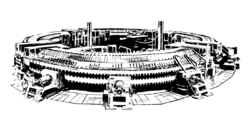

A synchrotron is a particular type of cyclic particle accelerator, descended from the cyclotron, in which the accelerating particle beam travels around a fixed closed-loop path. The strength of the magnetic field which bends the particle beam into its closed path increases with time during the accelerating process, being synchronized to the increasing kinetic energy of the particles.[1]

The synchrotron is one of the first accelerator concepts to enable the construction of large-scale facilities, since bending, beam focusing and acceleration can be separated into different components. The most powerful modern particle accelerators use versions of the synchrotron design. The largest synchrotron-type accelerator, also the largest particle accelerator in the world, is the 27-kilometre-circumference (17 mi) Large Hadron Collider (LHC) near Geneva, Switzerland, completed in 2008 by the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN).[2] It can accelerate beams of protons to an energy of 7 teraelectronvolts (TeV or 1012 eV).

Types

Large synchrotrons usually have a linear accelerator (linac) to give the particles an initial acceleration, and a lower energy synchrotron which is sometimes called a booster to increase the energy of the particles before they are injected into the high energy synchrotron ring. Several specialized types of synchrotron machines are used today:

- A collider is a type in which, instead of the particles striking a stationary target, particles traveling in two countercirculating rings collide head-on, making higher-energy collisions possible.[3][4]

- A storage ring is a special type of synchrotron in which the kinetic energy of the particles is kept constant.[5]

- A synchrotron light source is a combination of different electron accelerator types, including a storage ring in which the desired electromagnetic radiation is generated. This radiation is then used in experimental stations located on different beamlines. Synchrotron light sources in their entirety are sometimes called "synchrotrons", although this is technically incorrect.

Principle of operation

The synchrotron evolved from the cyclotron, the first cyclic particle accelerator. While a classical cyclotron uses both a constant guiding magnetic field and a constant-frequency electromagnetic field (and is working in classical approximation), its successor, the isochronous cyclotron, works by local variations of the guiding magnetic field, adapting to the increasing relativistic mass of particles during acceleration.[6]

While the first synchrotrons and storage rings like the Cosmotron and ADA strictly used the toroid shape, the strong focusing principle independently discovered by Ernest Courant et al.[7][8] and Nicholas Christofilos[9] allowed the complete separation of the accelerator into components with specialized functions along the particle path, shaping the path into a round-cornered polygon. Some important components are given by radio frequency cavities for direct acceleration, dipole magnets (bending magnets) for deflection of particles (to close the path), and quadrupole / sextupole magnets for beam focusing.[10]

Injection procedure

History and development

First generation synchrotrons

The synchrotron principle was proposed by Vladimir Veksler in 1944.[11] Edwin McMillan constructed the first electron synchrotron in 1945, arriving at the idea independently, having missed Veksler's publication (which was only available in a Soviet journal, although in English).[12][13][14]

The first proton synchrotron was designed by Sir Marcus Oliphant[13][15] and constructed at the University of Birmingham in 1952.[13] In 1963, McMillan and Veksler were jointly awarded the Atoms for Peace Prize for the invention of the synchrotron.[13]

One of the early large synchrotrons is the Bevatron, constructed in 1950 at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. The Bevatron can accelerate a proton with an energy of 6.2 GeV[16](then called BeV for billion electron volts; the name predates the adoption of the SI prefix giga-).[17] It can also accelerate heavier ions, such as deuterons, alpha-particles, and nitrogen.[18] A number of transuranium elements, unseen in the natural world, were first created with this instrument. This site is also the location of one of the first large bubble chambers are produced to examine the results of atomic collisions produced here.[19] In 1955, physicists Owen Chamberlain and Emilio Segrè had used the Bevatron to detect evidence for the existence of antiproton, for which they received the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physics.[20] The Bevatron was retired in February 1993.[21]

Another early large synchrotron is the Cosmotron built at Brookhaven National Laboratory which reached 3.3 GeV in 1953.[22]

Second generation synchrotrons

In the 1980s, detail about the second generation of synchrotrons began to emerge. These devices were constructed specifically for experiments with producing synchrotron radiation rather than particle physics research[23] The 2 GeV Synchrotron Radiation Source (SRS) at Daresbury, England, which operated in 1981, was the first of these "second-generation" synchrotron sources. Additionally, first generation synchrotrons are upgraded to become second generation sources.[24]

As part of colliders

Until August 2008, the highest energy collider in the world was the Tevatron, at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, in the United States. It accelerated protons and antiprotons to slightly less than 1 TeV of kinetic energy and collided them together. The Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which has been built at the European Laboratory for High Energy Physics (CERN), has roughly seven times this energy (so proton-proton collisions occur at roughly 14 TeV). It is housed in the 27.6 km tunnel which formerly housed the Large Electron Positron (LEP) collider.[25] The LHC will also accelerate heavy ions (such as lead) up to an energy of 1.15 PeV upon collision.[26] As of 2025, it is considered the largest and most powerful particle colldier.[27]

The largest device of this type seriously proposed was the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC), which was to be built in the United States. This design, like others, used superconducting magnets which allow more intense magnetic fields to be created without the limitations of core saturation.[28]: 10 While construction was begun, the project was cancelled in 1994, citing excessive budget overruns due to naïve cost estimation and economic management issues.[28]: 232–233 It can also be argued that the end of the Cold War resulted in a change of scientific funding priorities that contributed to its ultimate cancellation.[28]: 232–233 However, the tunnel built for its placement still remains, although empty.

As part of synchrotron light sources

Synchrotron radiation has a wide range of applications (see synchrotron light) and many second and third generation synchrotrons have been built especially to harness it. The largest of those 3rd generation synchrotron light sources are the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, the Advanced Photon Source (APS) in Lemont, United States, and SPring-8 in Hyōgo, Japan, accelerating electrons up to 6, 7 and 8 GeV, respectively.[29][30][31]

Synchrotrons are large devices, costing tens or hundreds of millions of dollars to construct, and each beamline (there may be 20 to 50 at a large synchrotron) costs another two or three million dollars on average.[32][33] These installations also require a large footprint. More compact models, such as the Munich Compact Light Source, have been developed and tested.[34]

Among the few synchrotrons around the world, 16 are located in the United States. Many of them belong to national laboratories; few are located in universities.[35]

Applications

- Life sciences: protein and large-molecule crystallography

- LIGA based microfabrication

- Drug discovery and research[36]

- X-ray lithography

- X-ray microtomography

- Analysing chemicals to determine their composition

- Observing the reaction of living cells to drugs

- Inorganic material crystallography and microanalysis

- Fluorescence studies

- Semiconductor material analysis and structural studies

- Geological material analysis

- Medical imaging

- Particle therapy to treat some forms of cancer

- Radiometry: calibration of detectors and radiometric standards

See also

- List of synchrotron radiation facilities

- Synchrotron radiation

- Cyclotron radiation

- Computed X-ray tomography

- Energy amplifier

- Superconducting radio frequency

- Coherent diffraction imaging

References

- ↑ Chao, A. W.; Mess, K. H.; Tigner, M. et al., eds (2013). Handbook of Accelerator Physics and Engineering (2nd ed.). World Scientific. doi:10.1142/8543. ISBN 978-981-4417-17-4. https://cds.cern.ch/record/384825.

- ↑ "The Large Hadron Collider" (in en). 2023-12-15. https://home.web.cern.ch/science/accelerators/large-hadron-collider.

- ↑ "The LHC as a photon collider | CMS Experiment". https://cms.cern/news/lhc-photon-collider.

- ↑ "The Large Hadron Collider" (in en). 2024-12-04. https://home.cern/science/accelerators/large-hadron-collider.

- ↑ "Storage Rings | Accelerator Directorate". https://accelerators.slac.stanford.edu/research/storage-rings.

- ↑ McMillan, Edwin M. (February 1984). "A history of the synchrotron" (in en). Physics Today 37 (2): 31–37. doi:10.1063/1.2916080. ISSN 0031-9228. http://physicstoday.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/1.2916080.

- ↑ Courant, E. D.; Livingston, M. S.; Snyder, H. S. (1952). "The Strong-Focusing Synchrotron—A New High Energy Accelerator". Physical Review 88 (5): 1190–1196. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.88.1190. Bibcode: 1952PhRv...88.1190C.

- ↑ Blewett, J. P. (1952). "Radial Focusing in the Linear Accelerator". Physical Review 88 (5): 1197–1199. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.88.1197. Bibcode: 1952PhRv...88.1197B.

- ↑ US patent 2736799, Nicholas Christofilos, "Focussing System for Ions and Electrons", issued 1956-02-28

- ↑ Muto, M.; Niki, K.; Mori, Y. (May 1997). "Magnets and their power supplies of JHF 50-GeV synchrotron". Proceedings of the 1997 Particle Accelerator Conference (Cat. No.97CH36167). 3. pp. 3306–3308 vol.3. doi:10.1109/PAC.1997.753190. ISBN 0-7803-4376-X.

- ↑ Veksler, V. I. (1944). "A new method of accelerating relativistic particles". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de l'URSS 43 (8): 346–348. http://lhe.jinr.ru/rus/veksler/wv0/publikacii/1944Veksler.pdf.

- ↑ J. David Jackson and W.K.H. Panofsky (1996). "EDWIN MATTISON MCMILLAN: A Biographical Memoir". National Academy of Sciences. http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/mcmillan-edwin.pdf.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Wilson, E. J. N. (1996). "Fifty Years of Synchrotrons". CERN. http://accelconf.web.cern.ch/accelconf/e96/PAPERS/ORALS/FRX04A.PDF.

- ↑ Zinovyeva, Larisa (10 June 2011). "On the question about the autophasing discovery authorship". Лариса Зиновьева. http://www.larisa-zinovyeva.com/%D0%B0%D0%B2%D1%82%D0%BE%D1%80%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%BE-%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%BA%D1%80%D1%8B%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%8F-%D0%B0%D0%B2%D1%82%D0%BE%D1%84%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BA%D0%B8/.

- ↑ Rotblat, Joseph (2000). "Obituary: Mark Oliphant (1901–2000)". Nature 407 (6803): 468. doi:10.1038/35035202. PMID 11028988.

- ↑ Lofgren, Edward J. (April 1959). "The Bevatron" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 45 (4): 451–456. doi:10.1073/pnas.45.4.451. ISSN 0027-8424. https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.45.4.451.

- ↑ "The Bevatron starts up at Berkeley, California". https://timeline.web.cern.ch/bevatron-starts-berkeley-california.

- ↑ Grunder, H. A.; Hartsough, W. D.; Lofgren, E. J. (1971-12-10). "Acceleration of Heavy Ions at the Bevatron". Science 174 (4014): 1128–1129. doi:10.1126/science.174.4014.1128. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.174.4014.1128.

- ↑ Historic American Engineering Record: University of California Radiation Laboratory, Bevatron. University of California Radiation Laboratory. September 1997. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/ca/ca2200/ca2289/data/ca2289data.pdf.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize for Physics for 1959: Dr. Emilio Segre and Dr. Owen Chamberlain" (in en). Nature 184 (4694): 1189–1189. October 1959. doi:10.1038/1841189a0. ISSN 1476-4687. https://www.nature.com/articles/1841189a0.

- ↑ Bodvarsson, Mary (February 26, 1993). "Bevatron Shutdown In 1993 Ceremony". https://www2.lbl.gov/Science-Articles/Archive/Bevalac-shutdown.html.

- ↑ "The Cosmotron". Brookhaven National Laboratory. http://www.bnl.gov/bnlweb/history/cosmotron.asp.

- ↑ Helliwell, John R. (August 1998). "Synchrotron radiation facilities". Nature Structural Biology 5 (8): 614–617. doi:10.1038/1307. ISSN 1072-8368. https://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/1307.

- ↑ Willmott, Philip (March 2019) (in en). An Introduction to Synchrotron Radiation: Techniques and Applications (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781119280453.ch1. ISBN 978-1-119-28039-2. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781119280453.

- ↑ Brüning, O.; Burkhardt, H.; Myers, S. (July 2012). "The large hadron collider" (in en). Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 67 (3): 705–734. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2012.03.001. Bibcode: 2012PrPNP..67..705B. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0146641012000695.

- ↑ Jowett, John M (October 1, 2008). "The LHC as a nucleus–nucleus collider". Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics 35 (10). doi:10.1088/0954-3899/35/10/104028. ISSN 0954-3899. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0954-3899/35/10/104028.

- ↑ Castelvecchi, Davide (2025-03-19). "The biggest machine in science: inside the fight to build the next giant particle collider" (in en). Nature 639 (8055): 560–563. doi:10.1038/d41586-025-00793-x. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 40108320. Bibcode: 2025Natur.639..560C. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00793-x.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Riordan, Michael; Hoddeson, Lillian; Kolb, Adrienne W. (2015). Tunnel visions: the rise and fall of the superconducting super collider. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-29479-7.

- ↑ Bruno, Patrick; Biasci, Jean-Claude; Detlefs, Carsten et al. (2024-10-24). "X-ray science using the ESRF—extremely brilliant source" (in en). The European Physical Journal Plus 139 (10): 928. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-024-05719-6. ISSN 2190-5444. Bibcode: 2024EPJP..139..928B.

- ↑ Galayda, J.N. (1995). "The Advanced Photon Source". Proceedings Particle Accelerator Conference. 1. pp. 4–8. doi:10.1109/PAC.1995.504556. ISBN 0-7803-2934-1.

- ↑ Kamitsubo, H. (1998-05-01). "SPring-8 Program". Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 5 (3): 162–167. doi:10.1107/S0909049597018517. ISSN 0909-0495. PMID 15263472. Bibcode: 1998JSynR...5..162K. https://journals.iucr.org/paper?S0909049597018517.

- ↑ Swinbanks, David (1996-12-01). "Costs cloud Korea's synchrotron expansion" (in en). Nature 384 (6608): 394–394. doi:10.1038/384394a0. ISSN 1476-4687. https://www.nature.com/articles/384394a0.

- ↑ Scott, Alex (2025-01-21). "U.K. Seeks To Enhance Its Synchrotron" (in en). https://cen.acs.org/articles/93/i36/UK-Seeks-Enhance-Synchrotron.html.

- ↑ Eggl, Elena; Dierolf, Martin; Achterhold, Klaus; Jud, Christoph; Günther, Benedikt; Braig, Eva; Gleich, Bernhard; Pfeiffer, Franz (September 1, 2016). "The Munich Compact Light Source: initial performance measures". Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 23 (5): 1137–1142. doi:10.1107/S160057751600967X. ISSN 1600-5775. https://journals.iucr.org/paper?S160057751600967X.

- ↑ "Synchrotron - All Items". https://nucleus.iaea.org/sites/accelerators/lists/synchrotron/allitems.aspx.

- ↑ Li, Fengcheng; Liu, Runze; Li, Wenjun; Xie, Mingyuan; Qin, Song (December 2024). "Synchrotron Radiation: A Key Tool for Drug Discovery" (in en). Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 114. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2024.129990. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0960894X24003925.

External links

- ESRF (European Synchrotron Radiation Facility)

- National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC) in Taiwan

- Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste - Elettra and Fermi lightsources

- Canadian Light Source

- Australian Synchrotron

- French synchrotron Soleil

- Diamond UK Synchrotron

- Lightsources.org

- IAEA database of electron synchrotron and storage rings

- CERN Large Hadron Collider

- Synchrotron Light Sources of the World

- A Miniature Synchrotron: room-size synchrotron offers scientists a new way to perform high-quality x-ray experiments in their own labs, Technology Review, February 4, 2008

- Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory

- Podcast interview with a scientist at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility

- Indian SRS

- Spanish ALBA Light Source

- The tabletop synchrotron MIRRORCLE

- SOLARIS synchrotron in Poland

|