Schwarz triangle tessellation

| Mathematical analysis → Complex analysis |

| Complex analysis |

|---|

|

| Complex numbers |

| Complex functions |

| Basic Theory |

| Geometric function theory |

| People |

|

|

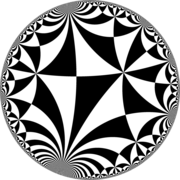

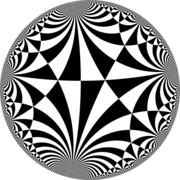

In mathematics, the Schwarz triangle tessellation was introduced by H. A. Schwarz as a way of tessellating the hyperbolic upper half plane by a Schwarz triangle, i.e. a geodesic triangle in the upper half plane with angles which are either 0 or of the form π over a positive integer greater than one. Through successive hyperbolic reflections in its sides, such a triangle generates a tessellation of the upper half plane (or the unit disk after composition with the Cayley transform). The hyperbolic refections generates a discrete group, with an orientation-preserving normal subgroup of index two. Each such tessellation yields a conformal mapping of the upper half plane onto the interior of the geodesic triangle, generalizing the Schwarz–Christoffel mapping, with the upper half plane replacing the complex plane. The corresponding inverse function, first defined by Schwarz, solved the problem of uniformization a hyperbolic triangle and is called the Schwarz triangle function.

Through the theory of complex ordinary differential equations with regular singular points and the Schwarzian derivative, the triangle function can be expressed as the quotient of two solutions of a hypergeometric differential equation with real coefficients and singular points at 0, 1 and ∞. By the Schwarz reflection principle, the reflection group induces an action on the two dimensional space of solutions. On the orientation-preserving normal subgroup, this two-dimensional representation corresponds to the monodromy of the ordinary differential equation and induces a group of Möbius transformations on quotients of hypergeometric functions.

As the inverse function of such a quotient, the triangle function is an automorphic function for this discrete group of Möbius transformations. This is a special case of a general scheme of Henri Poincaré that associates automorphic forms with ordinary differential equations with regular singular points. In the special case of ideal triangles, where all the angles are zero, the tessellation corresponds to the Farey tessellation and the triangle function yields the modular lambda function.

Hyperboloid and Beltrami-Klein models

In this section two different models are given for hyperbolic geometry on the unit disk or equivalently the upper half plane.[1]

The group G = SU(1,1) is formed of matrices

- [math]\displaystyle{ g = \begin{pmatrix} \alpha & \beta \\ \overline{\beta} & \overline{\alpha}\end{pmatrix} }[/math]

with

- [math]\displaystyle{ |\alpha|^2 -|\beta|^2=1. }[/math]

It is a subgroup of Gc = SL(2,C), the group of complex 2 × 2 matrices with determinant 1. The group Gc acts by Möbius transformations on the extended complex plane. The subgroup G acts as automorphisms of the unit disk D and the subgroup G1 = SL(2,R) acts as automorphisms of the upper half plane. If

- [math]\displaystyle{ C=\begin{pmatrix}1 & i \\ i & 1\end{pmatrix} }[/math]

then

- [math]\displaystyle{ G=CG_1C^{-1}, }[/math]

since the Möbius transformation corresponding M is the Cayley transform carrying the upper half plane onto the unit disk and the real line onto the unit circle.

The Lie algebra [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{g} }[/math] of SU(1,1) consists of matrices

- [math]\displaystyle{ X= \begin{pmatrix} ix & w \\ \overline{w} & -ix \end{pmatrix} }[/math]

with x real. Note that X2 = (|w|2 – x2) I and

- [math]\displaystyle{ \det X = x^2 -|w|^2 =-\tfrac12 \operatorname{Tr} X^2. }[/math]

The hyperboloid [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{H} }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{g} }[/math] is defined by two conditions. The first is that det X = 1 or equivalently Tr X2 = –2.[2] By definition this condition is preserved under conjugation by G. Since G is connected it leaves the two components with x > 0 and x < 0 invariant. The second condition is that x > 0. For brevity, write X = (x,w).

The group G acts transitively on D and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{H} }[/math] and the points 0 and (1,0) have stabiliser K consisting of matrices

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{pmatrix}\zeta & 0 \\ 0 & \overline{\zeta}\end{pmatrix} }[/math]

with |ζ| = 1. Polar decomposition on D implies the Cartan decomposition G = KAK where A is the group of matrices

- [math]\displaystyle{ a_t = \begin{pmatrix}\cosh t & \sinh t \\ \sinh t & \cosh t\end{pmatrix}. }[/math]

Both spaces can therefore be identified with the homogeneous space G/K and there is a G-equivariant map f of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{H} }[/math] onto D sending (1,0) to 0. To work out the formula for this map and its inverse it suffices to compute g(1,0) and g(0) where g is as above. Thus g(0) = β/α and

- [math]\displaystyle{ g(1,0)=(|\alpha|^2 +|\beta|^2,-2i\alpha\beta), }[/math]

so that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac\beta\overline{\alpha} = \frac{\alpha\beta} {|\alpha|{}^2} = \frac{2\alpha\beta}{|\alpha|{}^2 + |\beta|{}^2 + 1}, }[/math]

recovering the formula

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(x,w) = \frac{iw}{x + 1}. }[/math]

Conversely if z = iw/(x + 1), then |z|2 = (x – 1)/(x + 1), giving the inverse formula

- [math]\displaystyle{ f^{-1}(z) = (x,w) = \left( \frac{1 + |z|{}^2}{1 - |z|{}^2}, \frac{-2iz}{1 - |z|{}^2} \right). }[/math]

This correspondence extends to one between geometric properties of D and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{H} }[/math]. Without entering into the correspondence of G-invariant Riemannian metrics,[lower-alpha 1] each geodesic circle in D corresponds to the intersection of 2-planes through the origin, given by equations Tr XY = 0, with [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{H} }[/math]. Indeed, this is obvious for rays arg z = θ through the origin in D—which correspond to the 2-planes arg w = θ—and follows in general by G-equivariance.

The Beltrami-Klein model is obtained by using the map F(x,w) = w/x as the correspondence between [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{H} }[/math] and D. Identifying this disk with (1,v) with |v| < 1, intersections of 2-planes with [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{H} }[/math] correspond to intersections of the same 2-planes with this disk and so give straight lines. The Poincaré-Klein map given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ K(z) = iF \circ f^{-1}(z) = \frac{2z}{1 + |z|{}^2} }[/math]

thus gives a diffeomorphism from the unit disk onto itself such that Poincaré geodesic circles are carried into straight lines. This diffeomorphism does not preserve angles but preserves orientation and, like all diffeomorphisms, takes smooth curves through a point making an angle less than π (measured anticlockwise) into a similar pair of curves.[lower-alpha 2] In the limiting case, when the angle is π, the curves are tangent and this again is preserved under a diffeomorphism. The map K yields the Beltrami-Klein model of hyperbolic geometry. The map extends to a homeomorphism of the unit disk onto itself which is the identity on the unit circle. Thus by continuity the map K extends to the endpoints of geodesics, so carries the arc of the circle in the disc cutting the unit circle orthogonally at two given points on to the straight line segment joining those two points. The use of the Beltrami-Klein model corresponds to projective geometry and cross ratios. (Note that on the unit circle the radial derivative of K vanishes, so that the condition on angles no longer applies there.)[3][4]

The group G1 = SL(2,R) is formed of real matrices

- [math]\displaystyle{ g = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ c & d\end{pmatrix} }[/math]

with [math]\displaystyle{ ad -bc =1. }[/math] The action is by Möbius transformations on the upper half-plane. The Lie algebra of G1 is [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{g}_1 }[/math], the space of 2 x 2 real matrices of trace zero,

- [math]\displaystyle{ X = \begin{pmatrix} x & y-t \\ y+t & -x\end{pmatrix}. }[/math]

By transport of construction — conjugating by C — the symmetric bilinear form Tr ad(X)ad(Y) = 4 Tr XY is invariant under conjugation and has signature (2,1). As above X2 = (x2 + y2 – t2) I and

- [math]\displaystyle{ \det X = t^2 - x^2 - y^2 =-\tfrac12 \operatorname{Tr} X^2. }[/math]

By Sylvester's law of inertia,[5] the Killing form (or Cartan-Killing form) is, up to equivalence, the unique symmetric bilinear form of signature (2,1) with corresponding quadratic form –x2 –y2 +t2; and G / {±I} or equivalently G1 / {±I} can be identified with SO(2,1).

Convex polygons

In this section the main results on convexity of hyperbolic polygons are deduced from the corresponding results for Euclidean polygons by considering the relation between Poincaré's disk model and the Klein model. A polygon in the unit disk or upper half plane is made up of a collection of a finite set of vertices joined by geodesics, such that none of the geodesics intersect. In the Klein model this corresponds to the same picture in the Euclidean model with straight lines between the vertices. In the Euclidean model the polygon has an interior and exterior (by an elementary version of the Jordan curve theorem), so, since this is preserved under homeomorphism, the same is true in the Poincaré picture.

As a consequence at each vertex there is a well-defined notion of interior angle.

In the Euclidean plane a polygon with all its angles less than π is convex, i.e. the straight line joining interior points of the polygon also lies in the interior of the polygon. Since the Poincaré-Klein map preserves the property that angles are less than π, a hyperbolic polygon with interior angles less than π is carried onto a Euclidean polygon with the same property; the Euclidean polygon is therefore convex and hence, since hyperbolic geodesics are carried onto straight lines, so is the hyperbolic polygon. By a continuity argument, geodesics between points on the sides also lie in the closure of the polygon.

A similar convexity result holds for polygons which have some of their vertices on the boundary of the disk or the upper half plane. In fact each such polygon is an increasing union of polygons with angles less than π. Indeed, take points on the edges at each ideal vertex tending to the two edges joining those points to the ideal point with the geodesic joining them. Since two interior points of the original polygon will lie in the interior of one of these smaller polygons, each of which is convex, the original polygon must also be convex.[6]

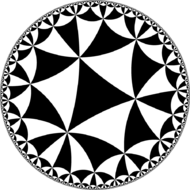

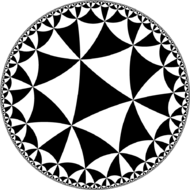

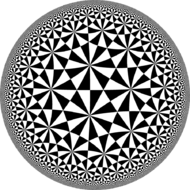

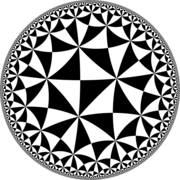

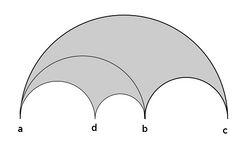

Tessellation by Schwarz triangles

In this section tessellations of the hyperbolic upper half plane by Schwarz triangles will be discussed using elementary methods. For triangles without "cusps"—angles equal to zero or equivalently vertices on the real axis—the elementary approach of (Carathéodory 1954) will be followed. For triangles with one or two cusps, elementary arguments of (Evans 1973), simplifying the approach of (Hecke 1935), will be used: in the case of a Schwarz triangle with one angle zero and another a right angle, the orientation-preserving subgroup of the reflection group of the triangle is a Hecke group. For an ideal triangle in which all angles are zero, so that all vertices lie on the real axis, the existence of the tessellation will be established by relating it to the Farey series described in (Hardy Wright) and (Series 2015). In this case the tessellation can be considered as that associated with three touching circles on the Riemann sphere, a limiting case of configurations associated with three disjoint non-nested circles and their reflection groups, the so-called "Schottky groups", described in detail in (Mumford Series). Alternatively—by dividing the ideal triangle into six triangles with angles 0, π/2 and π/3—the tessellation by ideal triangles can be understood in terms of tessellations by triangles with one or two cusps.

Triangles without cusps

Suppose that the hyperbolic triangle Δ has angles π/a, π/b and π/c with a, b, c integers greater than 1. The hyperbolic area of Δ equals π – π/a – π/b – π/c, so that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac1a + \frac1b + \frac1c \lt 1. }[/math]

The construction of a tessellation will first be carried out for the case when a, b and c are greater than 2.[7]

The original triangle Δ gives a convex polygon P1 with 3 vertices. At each of the three vertices the triangle can be successively reflected through edges emanating from the vertices to produce 2m copies of the triangle where the angle at the vertex is π/m. The triangles do not overlap except at the edges, half of them have their orientation reversed and they fit together to tile a neighborhood of the point. The union of these new triangles together with the original triangle form a connected shape P2. It is made up of triangles which only intersect in edges or vertices, forms a convex polygon with all angles less than or equal to π and each side being the edge of a reflected triangle. In the case when an angle of Δ equals π/3, a vertex of P2 will have an interior angle of π, but this does not affect the convexity of P2. Even in this degenerate case when an angle of π arises, the two collinear edge are still considered as distinct for the purposes of the construction.

The construction of P2 can be understood more clearly by noting that some triangles or tiles are added twice, the three which have a side in common with the original triangle. The rest have only a vertex in common. A more systematic way of performing the tiling is first to add a tile to each side (the reflection of the triangle in that edge) and then fill in the gaps at each vertex. This results in a total of 3 + (2a – 3) + (2b - 3) + (2c - 3) = 2(a + b + c) - 6 new triangles. The new vertices are of two types. Those which are vertices of the triangles attached to sides of the original triangle, which are connected to 2 vertices of Δ. Each of these lie in three new triangles which intersect at that vertex. The remainder are connected to a unique vertex of Δ and belong to two new triangles which have a common edge. Thus there are 3 + (2a – 4) + (2b - 4) + (2c - 4) = 2(a + b + c) - 9 new vertices. By construction there is no overlapping. To see that P2 is convex, it suffices to see that the angle between sides meeting at a new vertex make an angle less than or equal to π. But the new vertices lies in two or three new triangles, which meet at that vertex, so the angle at that vertex is no greater than 2π/3 or π, as required.

This process can be repeated for P2 to get P3 by first adding tiles to each edge of P2 and then filling in the tiles round each vertex of P2. Then the process can be repeated from P3, to get P4 and so on, successively producing Pn from Pn – 1. It can be checked inductively that these are all convex polygons, with non-overlapping tiles. Indeed, as in the first step of the process there are two types of tile in building Pn from Pn – 1, those attached to an edge of Pn – 1 and those attached to a single vertex. Similarly there are two types of vertex, one in which two new tiles meet and those in which three tiles meet. So provided that no tiles overlap, the previous argument shows that angles at vertices are no greater than π and hence that Pn is a convex polygon.[lower-alpha 3]

It therefore has to be verified that in constructing Pn from Pn − 1:[8]

(a) the new triangles do not overlap with Pn − 1 except as already described;

(b) the new triangles do not overlap with each other except as already described;

(c) the geodesic from any point in Δ to a vertex of the polygon Pn – 1 makes an angle ≤ 2π/3 with each of the edges of the polygon at that vertex.To prove (a), note that by convexity, the polygon Pn − 1 is the intersection of the convex half-spaces defined by the full circular arcs defining its boundary. Thus at a given vertex of Pn − 1 there are two such circular arcs defining two sectors: one sector contains the interior of Pn − 1, the other contains the interiors of the new triangles added around the given vertex. This can be visualized by using a Möbius transformation to map the upper half plane to the unit disk and the vertex to the origin; the interior of the polygon and each of the new triangles lie in different sectors of the unit disk. Thus (a) is proved.

Before proving (c) and (b), a Möbius transformation can be applied to map the upper half plane to the unit disk and a fixed point in the interior of Δ to the origin.

The proof of (c) proceeds by induction. Note that the radius joining the origin to a vertex of the polygon Pn − 1 makes an angle of less than 2π/3 with each of the edges of the polygon at that vertex if exactly two triangles of Pn − 1 meet at the vertex, since each has an angle less than or equal to π/3 at that vertex. To check this is true when three triangles of Pn − 1 meet at the vertex, C say, suppose that the middle triangle has its base on a side AB of Pn − 2. By induction the radii OA and OB makes angles of less than or equal to 2π/3 with the edge AB. In this case the region in the sector between the radii OA and OB outside the edge AB is convex as the intersection of three convex regions. By induction the angles at A and B are greater than or equal to π/3. Thus the geodesics to C from A and B start off in the region; by convexity, the triangle ABC lies wholly inside the region. The quadrilateral OACB has all its angles less than π (since OAB is a geodesic triangle), so is convex. Hence the radius OC lies inside the angle of the triangle ABC near C. Thus the angles between OC and the two edges of Pn – 1 meeting at C are less than or equal to π/3 + π/3 = 2π/3, as claimed.

To prove (b), it must be checked how new triangles in Pn intersect.

First consider the tiles added to the edges of Pn – 1. Adopting similar notation to (c), let AB be the base of the tile and C the third vertex. Then the radii OA and OB make angles of less than or equal to 2π/3 with the edge AB and the reasoning in the proof of (c) applies to prove that the triangle ABC lies within the sector defined by the radii OA and OB. This is true for each edge of Pn – 1. Since the interiors of sectors defined by distinct edges are disjoint, new triangles of this type only intersect as claimed.

Next consider the additional tiles added for each vertex of Pn – 1. Taking the vertex to be A, three are two edges AB1 and AB2 of Pn – 1 that meet at A. Let C1 and C2 be the extra vertices of the tiles added to these edges. Now the additional tiles added at A lie in the sector defined by radii OB1 and OB2. The polygon with vertices C2 O, C1, and then the vertices of the additional tiles has all its internal angles less than π and hence is convex. It is therefore wholly contained in the sector defined by the radii OC1 and OC2. Since the interiors of these sectors are all disjoint, this implies all the claims about how the added tiles intersect.

Finally it remains to prove that the tiling formed by the union of the triangles covers the whole of the upper half plane. Any point z covered by the tiling lies in a polygon Pn and hence a polygon Pn +1 . It therefore lies in a copy of the original triangle Δ as well as a copy of P2 entirely contained in Pn +1 . The hyperbolic distance between Δ and the exterior of P2 is equal to r > 0. Thus the hyperbolic distance between z and points not coverered by the tiling is at least r. Since this applies to all points in the tiling, the set covered by the tiling is closed. On the other hand, the tiling is open since it coincides with the union of the interiors of the polygons Pn. By connectivity, the tessellation must cover the whole of the upper half plane.

To see how to handle the case when an angle of Δ is a right angle, note that the inequality

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac1a + \frac1b + \frac1c \lt 1 }[/math].

implies that if one of the angles is a right angle, say a = 2, then both b and c are greater than 2 and one of them, b say, must be greater than 3. In this case, reflecting the triangle across the side AB gives an isosceles hyperbolic triangle with angles π/c, π/c and 2π/b. If 2π/b ≤ π/3, i.e. b is greater than 5, then all the angles of the doubled triangle are less than or equal to π/3. In that case the construction of the tessellation above through increasing convex polygons adapts word for word to this case except that around the vertex with angle 2π/b, only b—and not 2b—copies of the triangle are required to tile a neighborhood of the vertex. This is possible because the doubled triangle is isosceles. The tessellation for the doubled triangle yields that for the original triangle on cutting all the larger triangles in half.[9]

It remains to treat the case when b equals 4 or 5. If b = 4, then c ≥ 5: in this case if c ≥ 6, then b and c can be switched and the argument above applies, leaving the case b = 4 and c = 5. If b = 5, then c ≥ 4. The case c ≥ 6 can be handled by swapping b and c, so that the only extra case is b = 5 and c = 5. This last isosceles triangle is the doubled version of the first exceptional triangle, so only that triangle Δ1—with angles π/2, π/4 and π/5 and hyperbolic area π/20—needs to be considered (see below). (Carathéodory 1954) handles this case by a general method which works for all right angled triangles for which the two other angles are less than or equal to π/4. The previous method for constructing P2, P3, ... is modified by adding an extra triangle each time an angle 3π/2 arises at a vertex. The same reasoning applies to prove there is no overlapping and that the tiling covers the hyperbolic upper half plane.[9]

On the other hand, the given configuration gives rise to an arithmetic triangle group. These were first studied in (Fricke Klein). and have given rise to an extensive literature. In 1977 Takeuchi obtained a complete classification of arithmetic triangle groups (there are only finitely many) and determined when two of them are commensurable. The particular example is related to Bring's curve and the arithmetic theory implies that the triangle group for Δ1 contains the triangle group for the triangle Δ2 with angles π/4, π/4 and π/5 as a non-normal subgroup of index 6.[10]

Doubling the triangles Δ1 and Δ2, this implies that there should be a relation between 6 triangles Δ3 with angles π/2, π/5 and π/5 and hyperbolic area π/10 and a triangle Δ4 with angles π/5, π/5 and π/10 and hyperbolic area 3π/5. (Threlfall 1932) established such a relation directly by completely elementary geometric means, without reference to the arithmetic theory: indeed as illustrated in the fifth figure below, the quadrilateral obtained by reflecting across a side of a triangle of type Δ4 can be tiled by 12 triangles of type Δ3. The tessellation by triangles of the type Δ4 can be handled by the main method in this section; this therefore proves the existence of the tessellation by triangles of type Δ3 and Δ1.[11]

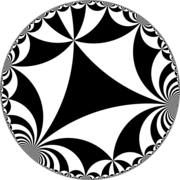

Triangles with one or two cusps

In the case of a Schwarz triangle with one or two cusps, the process of tiling becomes simpler; but it is easier to use a different method going back to Hecke to prove that these exhaust the hyperbolic upper half plane.

In the case of one cusp and non-zero angles π/a, π/b with a, b integers greater than one, the tiling can be envisaged in the unit disk with the vertex having angle π/a at the origin. The tiling starts by adding 2a – 1 copies of the triangle at the origin by successive reflections. This results in a polygon P1 with 2a cusps and between each two 2a vertices each with an angle π/b. The polygon is therefore convex. For each non-ideal vertex of P1, the unique triangle with that vertex can be similar reflected around that vertex, thus adding 2b – 1 new triangles, 2b – 1 new ideal points and 2 b – 1 new vertices with angle π/a. The resulting polygon P2 is thus made up of 2a(2b – 1) cusps and the same number of vertices each with an angle of π/a, so is convex. The process can be continued in this way to obtain convex polygons P3, P4, and so on. The polygon Pn will have vertices having angles alternating between 0 and π/a for n even and between 0 and π/b for n odd. By construction the triangles only overlap at edges or vertices, so form a tiling.[12]

The case where the triangle has two cusps and one non-zero angle π/a can be reduced to the case of one cusp by observing that the trinale is the double of a triangle with one cusp and non-zero angles π/a and π/b with b = 2. The tiling then proceeds as before.[13]

To prove that these give tessellations, it is more convenient to work in the upper half plane. Both cases can be treated simultaneously, since the case of two cusps is obtained by doubling a triangle with one cusp and non-zero angles π/a and π/2. So consider the geodesic triangle in the upper half plane with angles 0, π/a, π/b with a, b integers greater than one. The interior of such a triangle can be realised as the region X in the upper half plane lying outside the unit disk |z| ≤ 1 and between two lines parallel to the imaginary axis through points u and v on the unit circle. Let Γ be the triangle group generated by the three reflections in the sides of the triangle.

To prove that the successive reflections of the triangle cover the upper half plane, it suffices to show that for any z in the upper half plane there is a g in Γ such that g(z) lies in X. This follows by an argument of (Evans 1973), simplified from the theory of Hecke groups. Let λ = Re a and μ = Re b so that, without loss of generality, λ < 0 ≤ μ. The three reflections in the sides are given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_1(z) = \frac1\overline{z},\ R_2(z) = -\overline{z} + \lambda,\ R_3(z)= -\overline{z} + \mu. }[/math]

Thus T = R3∘R2 is translation by μ − λ. It follows that for any z1 in the upper half plane, there is an element g1 in the subgroup Γ1 of Γ generated by T such that w1 = g1(z1) satisfies λ ≤ Re w1 ≤ μ, i.e. this strip is a fundamental domain for the translation group Γ1. If |w1| ≥ 1, then w1 lies in X and the result is proved. Otherwise let z2 = R1(w1) and find g2 Γ1 such that w2 = g2(z2) satisfies λ ≤ Re w2 ≤ μ. If |w2| ≥ 1 then the result is proved. Continuing in this way, either some wn satisfies |wn| ≥ 1, in which case the result is proved; or |wn| < 1 for all n. Now since gn + 1 lies in Γ1 and |wn| < 1,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Im} g_{n+1}(z_{n+1}) = \operatorname{Im} z_{n+1} = \operatorname{Im} \frac{w_n}{|w_n|{}^2} = \frac{\operatorname{Im} w_n}{|w_n|{}^2}. }[/math]

In particular

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Im} w_{n+1} \ge \operatorname{Im} w_n }[/math]

and

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\operatorname{Im} w_{n+1}}{\operatorname{Im} w_n} = |w_n|^{-2} \ge 1. }[/math]

Thus, from the inequality above, the points (wn) lies in the compact set |z| ≤ 1, λ ≤ Re z ≤ μ and Im z ≥ Im w 1. It follows that |wn| tends to 1; for if not, then there would be an r < 1 such that |wm| ≤ r for inifitely many m and then the last equation above would imply that Im wn tends to infinity, a contradiction.

Let w be a limit point of the wn, so that |w| = 1. Thus w lies on the arc of the unit circle between u and v. If w ≠ u, v, then R1 wn would lie in X for n sufficiently large, contrary to assumption. Hence w =u or v. Hence for n sufficiently large wn lies close to u or v and therefore must lie in one of the reflections of the triangle about the vertex u or v, since these fill out neighborhoods of u and v. Thus there is an element g in Γ such that g(wn) lies in X. Since by construction wn is in the Γ-orbit of z1, it follows that there is a point in this orbit lying in X, as required.[14]

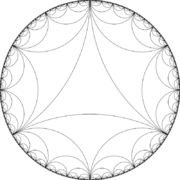

Ideal triangles

The tessellation for an ideal triangle with all its vertices on the unit circle and all its angles 0 can be considered as a special case of the tessellation for a triangle with one cusp and two now zero angles π/3 and π/2. Indeed, the ideal triangle is made of six copies one-cusped triangle obtained by reflecting the smaller triangle about the vertex with angle π/3.

Each step of the tiling, however, is uniquely determined by the positions of the new cusps on the circle, or equivalently the real axis; and these points can be understood directly in terms of Farey series following (Series 2015), (Hatcher 2013) and (Hardy Wright). This starts from the basic step that generates the tessellation, the reflection of an ideal triangle in one of its sides. Reflection corresponds to the process of inversion in projective geometry and taking the projective harmonic conjugate, which can be defined in terms of the cross ratio. In fact if p, q, r, s are distinct points in the Riemann sphere, then there is a unique complex Möbius transformation g sending p, q and s to 0, ∞ and 1 respectively. The cross ratio (p, q; r, s) is defined to be g(r) and is given by the formula

- [math]\displaystyle{ (p, q; r, s) = \frac{(p-r)(q-s)}{(p-s)(q-r)}. }[/math]

By definition it is invariant under Möbius transformations. If a, b lie on the real axis, the harmonic conjugate of c with respect to a and b is defined to be the unique real number d such that (a, b; c, d) = −1. So for example if a = 1 and b = –1, the conjugate of r is 1/r. In general Möbius invariance can be used to obtain an explicit formula for d in terms of a, b and c. Indeed, translating the centre t = (a + b)/2 of the circle with diameter having endpoints a and b to 0, d – t is the harmonic conjugate of c – t with respect to a - t and b – t. The radius of the circle is ρ = (b – a)/2 so (d - t)/ρ is the harmonic conjugate of (c – t)/ρ with respect to 1 and -1. Thus

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{d-t}\rho = \frac\rho{c-t} }[/math]

so that

- [math]\displaystyle{ d = \frac{\rho^2}{r-t} + t = \frac{(c-a)b + (c-b)a}{(c-a) + (c-b)}. }[/math]

It will now be shown that there is a parametrisation of such ideal triangles given by rationals in reduced form

- [math]\displaystyle{ a = \frac{p_1}{q_1},\ b = \frac{p_1 + p_2}{q_1 + q_2},\ c = \frac{p_2}{q_2} }[/math]

with a and c satisfying the "neighbour condition" p2q1 − q2p1 = 1.

The middle term b is called the Farey sum or mediant of the outer terms and written

- [math]\displaystyle{ b = a \oplus c. }[/math]

The formula for the reflected triangle gives

- [math]\displaystyle{ d = \frac{p_1 + 2p_2}{q_1 + 2q_2} = a \oplus b. }[/math]

Similarly the reflected triangle in the second semicircle gives a new vertex b ⊕ c. It is immediately verified that a and b satisfy the neighbour condition, as do b and c.

Now this procedure can be used to keep track of the triangles obtained by successively reflecting the basic triangle Δ with vertices 0, 1 and ∞. It suffices to consider the strip with 0 ≤ Re z ≤ 1, since the same picture is reproduced in parallel strips by applying reflections in the lines Re z = 0 and 1. The ideal triangle with vertices 0, 1, ∞ reflects in the semicircle with base [0,1] into the triangle with vertices a = 0, b = 1/2, c = 1. Thus a = 0/1 and c = 1/1 are neighbours and b = a ⊕ c. The semicircle is split up into two smaller semicircles with bases [a,b] and [b,c]. Each of these intervals splits up into two intervals by the same process, resulting in 4 intervals. Continuing in this way, results into subdivisions into 8, 16, 32 intervals, and so on. At the nth stage, there are 2n adjacent intervals with 2n + 1 endpoints. The construction above shows that successive endpoints satisfy the neighbour condition so that new endpoints resulting from reflection are given by the Farey sum formula.

To prove that the tiling covers the whole hyperbolic plane, it suffices to show that every rational in [0,1] eventually occurs as an endpoint. There are several ways to see this. One of the most elementary methods is described in (Graham Knuth) in their development—without the use of continued fractions—of the theory of the Stern-Brocot tree, which codifies the new rational endpoints that appear at the nth stage. They give a direct proof that every rational appears. Indeed, starting with {0/1,1/1}, successive endpoints are introduced at level n+1 by adding Farey sums or mediants (p+r)/(q+s) between all consecutive terms p/q, r/s at the nth level (as described above). Let x = a/b be a rational lying between 0 and 1 with a and b coprime. Suppose that at some level x is sandwiched between successive terms p/q < x < r/s. These inequalities force aq – bp ≥ 1 and br – as ≥ 1 and hence, since rp – qs = 1,

- [math]\displaystyle{ a + b = (r+s)(ap-bq) + (p+q)(br -as) \ge p+q+r+s. }[/math]

This puts an upper bound on the sum of the numerators and denominators. On the other hand, the mediant (p+r)/(q+s) can be introduced and either equals x, in which case the rational x appears at this level; or the mediant provides a new interval containing x with strictly larger numerator-and-denominator sum. The process must therefore terminate after at most a + b steps, thus proving that x appears.[15]

A second approach relies on the modular group G = SL(2,Z).[16] The Euclidean algorithm implies that this group is generated by the matrices

- [math]\displaystyle{ S=\begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1\\ -1 & 0 \end{pmatrix},\,\,\, T=\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1\\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}. }[/math]

In fact let H be the subgroup of G generated by S and T. Let

- [math]\displaystyle{ g=\begin{pmatrix} a & b\\ c & d\end {pmatrix} }[/math]

be an element of SL(2,Z). Thus ad − cb = 1, so that a and c are coprime. Let

- [math]\displaystyle{ v=\begin{pmatrix}a\\ c\end{pmatrix},\,\,\, u= \begin{pmatrix}1\\ 0\end{pmatrix}. }[/math]

Applying S if necessary, it can be assumed that |a| > |c| (equality is not possible by coprimeness). We write a = mc + r with 0 ≤ r ≤ |c|. But then

- [math]\displaystyle{ T^{-m}\begin{pmatrix} a\\ c \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} r\\ c\end{pmatrix}. }[/math]

This process can be continued until one of the entries is 0, in which case the other is necessarily ±1. Applying a power of S if necessary, it follows that v = h u for some h in H. Hence

- [math]\displaystyle{ h^{-1}g=\begin{pmatrix}1 & p\\ 0 & q\end{pmatrix} }[/math]

with p, q integers. Clearly p = 1, so that h−1g = Tq. Thus g = h Tq lies in H as required.

To prove that all rationals in [0,1] occur, it suffices to show that G carries Δ onto triangles in the tessellation. This follows by first noting that S and T carry Δ on to such a triangle: indeed as Möbius transformations, S(z) = –1/z and T(z) = z + 1, so these give reflections of Δ in two of its sides. But then S and T conjugate the reflections in the sides of Δ into reflections in the sides of SΔ and TΔ, which lie in Γ. Thus G normalizes Γ. Since triangles in the tessellation are exactly those of the form gΔ with g in Γ, it follows that S and T, and hence all elements of G, permute triangles in the tessellation. Since every rational is of the form g(0) for g in G, every rational in [0,1] is the vertex of a triangle in the tessellation.

The reflection group and tessellation for an ideal triangle can also be regarded as a limiting case of the Schottky group for three disjoint unnested circles on the Riemann sphere. Again this group is generated by hyperbolic reflections in the three circles. In both cases the three circles have a common circle which cuts them orthogonally. Using a Möbius transformation, it may be assumed to be the unit circle or equivalently the real axis in the upper half plane.[17]

Approach of Siegel

In this subsection the approach of Carl Ludwig Siegel to the tessellation theorem for triangles is outlined. Siegel's less elementary approach does not use convexity, instead relying on the theory of Riemann surfaces, covering spaces and a version of the monodromy theorem for coverings. It has been generalized to give proofs of the more general Poincaré polygon theorem. (Note that the special case of tiling by regular n-gons with interior angles 2π/n is an immediate consequence of the tessellation by Schwarz triangles with angles π/n, π/n and π/2.)[18][19]

Let Γ be the free product Z2 ∗ Z2 ∗ Z2. If Δ = ABC is a Schwarz triangle with angles π/a, π/b and π/c, where a, b, c ≥ 2, then there is a natural map of Γ onto the group generated by reflections in the sides of Δ. Elements of Γ are described by a product of the three generators where no two adjacent generators are equal. At the vertices A, B and C the product of reflections in the sides meeting at the vertex define rotations by angles 2π/a, 2π/b and 2π/c; Let gA, gB and gC be the corresponding products of generators of Γ = Z2 ∗ Z2 ∗ Z2. Let Γ0 be the normal subgroup of index 2 of Γ, consisting of elements that are the product of an even number of generators; and let Γ1 be the normal subgroup of Γ generated by (gA)a, (gB)b and (gC)c. These act trivially on Δ. Let Γ = Γ/Γ1 and Γ0 = Γ0/Γ1.

The disjoint union of copies of Δ indexed by elements of Γ with edge identifications has the natural structure of a Riemann surface Σ. At an interior point of a triangle there is an obvious chart. As a point of the interior of an edge the chart is obtained by reflecting the triangle across the edge. At a vertex of a triangle with interior angle π/n, the chart is obtained from the 2n copies of the triangle obtained by reflecting it successively around that vertex. The group Γ acts by deck transformations of Σ, with elements in Γ0 acting as holomorphic mappings and elements not in Γ0 acting as antiholomorphic mappings.

There is a natural map P of Σ into the hyperbolic plane. The interior of the triangle with label g in Γ is taken onto g(Δ), edges are taken to edges and vertices to vertices. It is also easy to verify that a neighbourhood of an interior point of an edge is taken into a neighbourhood of the image; and similarly for vertices. Thus P is locally a homeomorphism and so takes open sets to open sets. The image P(Σ), i.e. the union of the translates g(Δ), is therefore an open subset of the upper half plane. On the other hand, this set is also closed. Indeed, if a point is sufficiently close to Δ it must be in a translate of Δ. Indeed, a neighbourhood of each vertex is filled out the reflections of Δ and if a point lies outside these three neighbourhoods but is still close to Δ it must lie on the three reflections of Δ in its sides. Thus there is δ > 0 such that if z lies within a distance less than δ from Δ, then z lies in a Γ-translate of Δ. Since the hyperbolic distance is Γ-invariant, it follows that if z lies within a distance less than δ from Γ(Δ) it actually lies in Γ(Δ), so this union is closed. By connectivity it follows that P(Σ) is the whole upper half plane.

On the other hand, P is a local homeomorphism, so a covering map. Since the upper half plane is simply connected, it follows that P is one-one and hence the translates of Δ tessellate the upper half plane. This is a consequence of the following version of the monodromy theorem for coverings of Riemann surfaces: if Q is a covering map between Riemann surfaces Σ1 and Σ2, then any path in Σ2 can be lifted to a path in Σ1 and any two homotopic paths with the same end points lift to homotopic paths with the same end points; an immediate corollary is that if Σ2 is simply connected, Q must be a homeomorphism.[20] To apply this, let Σ1 = Σ, let Σ2 be the upper half plane and let Q = P. By the corollary of the monodromy theorem, P must be one-one.

It also follows that g(Δ) = Δ if and only if g lies in Γ1, so that the homomorphism of Γ0 into the Möbius group is faithful.

Hyperbolic reflection groups

The tessellation of the Schwarz triangles can be viewed as a generalization of the theory of infinite Coxeter groups, following the theory of hyperbolic reflection groups developed algebraically by Jacques Tits[21] and geometrically by Ernest Vinberg.[22] In the case of the Lobachevsky or hyperbolic plane, the ideas originate in the nineteenth-century work of Henri Poincaré and Walther von Dyck. As Joseph Lehner has pointed out in Mathematical Reviews, however, rigorous proofs that reflections of a Schwarz triangle generate a tessellation have often been incomplete, his own 1964 book "Discontinuous Groups and Automorphic Forms", being one example.[23][24] Carathéodory's elementary treatment in his 1950 textbook "Funktiontheorie", translated into English in 1954, and Siegel's 1954 account using the monodromy principle are rigorous proofs. The approach using Coxeter groups will be summarised here, within the general framework of classification of hyperbolic reflection groups.[25]

Let r, s and t be symbols and let a, b, c ≥ 2 be integers, possibly ∞, with

- [math]\displaystyle{ {1 \over a} + {1 \over b} + {1 \over c} \lt 1. }[/math]

Define Γ to be the group with presentation having generators r, s and t that are all involutions and satisfy (st)a = 1, (tr)b = 1 and (rs)c = 1. If one of the integers is infinite, then the product has infinite order. The generators r, s and t are called the simple reflections.

Set A = cos π / a if a ≥ 2 is finite and cosh x with x > 0 otherwise; similarly set B = cos π / b or cosh y and C = cos π / c or cosh z.[26] Let er, es and et be a basis for a 3-dimensional real vector space V with symmetric bilinear form Λ such that Λ(es,et) = − A, Λ(et,er) = − B and Λ(er,es) = − C, with the three diagonal entries equal to one. The symmetric bilinear form Λ is non-degenerate with signature (2,1). Define ρ(v) = v − 2 Λ(v,er) er, σ(v) = v − 2 Λ(v,es) es and τ(v) = v − 2 Λ(v,et) et.

Theorem (geometric representation). The operators ρ, σ and τ are involutions on V, with respective eigenvectors er, es and et with simple eigenvalue −1. The products of the operators have orders corresponding to the presentation above (so στ has order a, etc). The operators ρ, σ and τ induce a representation of Γ on V which preserves Λ.

The bilinear form Λ for the basis has matrix

- [math]\displaystyle{ M = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & -C & -B\\ -C & 1 & -A\\ -B & -A & 1\\ \end{pmatrix}, }[/math]

so has determinant 1−A2−B2−C2−2ABC. If c = 2, say, then the eigenvalues of the matrix are 1 and 1 ± (A2+B2)½. The condition a−1 + b−1 < ½ immediately forces A2+B2 > 1, so that Λ must have signature (2,1). So in general a, b, c ≥ 3. Clearly the case where all are equal to 3 is impossible. But then the determinant of the matrix is negative while its trace is positive. As a result two eigenvalues are positive and one negative, i.e. Λ has signature (2,1). Manifestly ρ, σ and τ are involutions, preserving Λ with the given −1 eigenvectors.

To check the order of the products like στ, it suffices to note that:

- the reflections σ and τ generate a finite or infinite dihedral group;

- the 2-dimensional linear span U of es and et is invariant under σ and τ, with the restriction of Λ positive-definite;

- W, the orthogonal complement of U, is negative-definite on Λ, and σ and τ act trivially on W.

(1) is clear since if γ = στ generates a normal subgroup with σγσ–1 = γ–1. For (2), U is invariant by definition and the matrix is positive-definite since 0 < cos π / a < 1. Since Λ has signature (2,1), a non-zero vector w in W must satisfy Λ(w,w) < 0. By definition, σ has eigenvalues 1 and –1 on U, so w must be fixed by σ. Similarly w must be fixed by τ, so that (3) is proved. Finally in (1)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma ({\mathbf e}_s) = -{\mathbf e}_s,\,\,\,\,\, \sigma({\mathbf e}_t) = 2 \cos(\pi / a) {\mathbf e}_s + {\mathbf e}_t,\,\,\,\,\, \tau({\mathbf e}_s) = 2 \cos(\pi / a) {\mathbf e}_s + {\mathbf e}_t,\,\,\,\,\, \tau({\mathbf e}_t) = -{\mathbf e}_t, }[/math]

so that, if a is finite, the eigenvalues of στ are -1, ς and ς–1, where ς = exp 2πi / a; and if a is infinite, the eigenvalues are -1, X and X–1, where X = exp 2x. Moreover a straightforward induction argument shows that if θ = π / a then[27]

- [math]\displaystyle{ (\sigma\tau)^m({\mathbf e}_s) = [\sin(2m+1)\theta/\sin\theta]{\mathbf e}_s + [\sin 2m\theta/\sin\theta]{\mathbf e}_t, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tau(\sigma\tau)^m({\mathbf e}_s) = [\sin(2m+1)\theta/\sin\theta]{\mathbf e}_s + [\sin (2m+2)\theta/\sin\theta]{\mathbf e}_t }[/math]

and if x > 0 then

- [math]\displaystyle{ (\sigma\tau)^m({\mathbf e}_s) = [\sinh(2m+1)x/\sinh x]{\mathbf e}_s + [\sinh 2mx/\sinh x]{\mathbf e}_t, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \tau(\sigma\tau)^m({\mathbf e}_s) = [\sinh(2m+1)x/\sinh x]{\mathbf e}_s + [\sinh (2m+2)x/\sinh x]{\mathbf e}_t. }[/math][28]

Let Γa be the dihedral subgroup of Γ generated by s and t, with analogous definitions for Γb and Γc. Similarly define Γr to be the cyclic subgroup of Γ given by the 2-group {1,r}, with analogous definitions for Γs and Γt. From the properties of the geometric representation, all six of these groups act faithfully on V. In particular Γa can be identified with the group generated by σ and τ; as above it decomposes explicitly as a direct sum of the 2-dimensional irreducible subspace U and the 1-dimensional subspace W with a trivial action. Thus there is a unique vector w = er + λ es + μ et in W satisfying σ(w) = w and τ(w) = w. Explicitly λ = (C + AB)/(1 – A2) and μ = (B + AC)/(1 – A2).

Remark on representations of dihedral groups. It is well known that, for finite-dimensional real inner product spaces, two orthogonal involutions S and T can be decomposed as an orthogonal direct sum of 2-dimensional or 1-dimensional invariant spaces; for example, this can be deduced from the observation of Paul Halmos and others, that the positive self-adjoint operator (S – T)2 commutes with both S and T. In the case above, however, where the bilinear form Λ is no longer a positive definite inner product, different ad hoc reasoning has to be given.

Theorem (Tits). The geometric representation of the Coxeter group is faithful.

This result was first proved by Tits in the early 1960s and first published in the text of (Bourbaki 1968) with its numerous exercises. In the text, the fundamental chamber was introduced by an inductive argument; exercise 8 in §4 of Chapter V was expanded by Vinay Deodhar to develop a theory of positive and negative roots and thus shorten the original argument of Tits.[29]

Let X be the convex cone of sums κer + λes + μet with real non-negative coefficients, not all of them zero. For g in the group Γ, define ℓ(g), the word length or length, to be the minimum number of reflections from r, s and t required to write g as an ordered composition of simple reflections. Define a positive root to be a vector ger, ges or ger lying in X, with g in Γ.[30]

It is routine to check from the definitions that[31]

- if |ℓ(gq) – ℓ(g)| = 1 for a simple reflection q and, if g ≠ 1, there is always a simple reflection q such that ℓ(g) = ℓ(gq) + 1;

- for g and h in Γ, ℓ(gh) ≤ ℓ(g) + ℓ(h).

Proposition. If g is in Γ and ℓ(gq) = ℓ(g) ± 1 for a simple reflection q, then geq lies in ±X, and is therefore a positive or negative root, according to the sign.

Replacing g by gq, only the positive sign needs to be considered. The assertion will be proved by induction on ℓ(g) = m, it being trivial for m = 0. Assume that ℓ(gs) = ℓ(g) + 1. If ℓ(g) = m > 0, without less of generality it may be assumed that the minimal expression for g ends with ...t. Since s and t generate the dihedral group Γa, g can be written as a product g = hk, where k = (st)n or t(st)n and h has a minimal expression that ends with ...r, but never with s or t. This implies that ℓ(hs) = ℓ(h) + 1 and ℓ(ht) = ℓ(h) + 1. Since ℓ(h) < m, the induction hypothesis shows that both hes and het lie in X. It therefore suffices to show that kes has the form λes + μet with λ, μ ≥ 0, not both 0. But that has already been verified in the formulas above.[31]

Corollary (proof of Tits' theorem). The geometric representation is faithful.

It suffices to show that if g fixes er, es and et, then g = 1. Considering a minimal expression for g ≠ 1, the conditions ℓ(gq) = ℓ(g) + 1 clearly cannot be simultaneously satisfied by the three simple reflections q.

Note that, as a consequence of Tits' theorem, the generators g = st, h = tr and k = rs satisfy ga = 1, hb = 1 and kc = 1 with ghk = 1. This gives a presentation of the orientation-preserving index 2 normal subgroup Γ1 of Γ. The presentation corresponds to the fundamental domain obtained by reflecting two sides of the geodesic triangle to form a geodesic parallelogram (a special case of Poincaré's polygon theorem).[32]

Further consequences. The roots are the disjoint union of the positive roots and the negative roots. The simple reflection q permutes every positive root other than eq. For g in Γ, ℓ(g) is the number of positive roots made negative by g.

Fundamental domain and Tits cone.[33]

Let G be the 3-dimensional closed Lie subgroup of GL(V) preserving Λ. As V can be identified with a 3-dimensional Lorentzian or Minkowski space with signature (2,1), the group G is isomorphic to the Lorentz group O(2,1) and therefore SL±(2,R) / {±I}.[34] Choosing e to be a positive root vector in X, the stabilizer of e is a maximal compact subgroup K of G isomorphic to O(2). The homogeneous space X = G / K is a symmetric space of constant negative curvature, which can be identified with the 2-dimensional hyperboloid or Lobachevsky plane [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{H}^2 }[/math]. The discrete group Γ acts discontinuously on G / K: the quotient space Γ \ G / K is compact if a, b and c are all finite, and of finite area otherwise. Results about the Tits fundamental chamber have a natural interpretation in terms of the corresponding Schwarz triangle, which translate directly into the properties of the tessellation of the geodesic triangle through the hyperbolic reflection group Γ. The passage from Coxeter groups to tessellation can first be found in the exercises of §4 of Chapter V of (Bourbaki 1968), due to Tits, and in (Iwahori 1966); currently numerous other equivalent treatments are available, not always directly phrased in terms of symmetric spaces.

Approach of Maskit, de Rham and Beardon

(Maskit 1971) gave a general proof of Poincaré's polygon theorem in hyperbolic space; a similar proof was given in (de Rham 1971). Specializing to the hyperbolic plane and Schwarz triangles, this can be used to give a modern approach for establishing that the existence of Schwarz triangle tessellations, as described in (Beardon 1983) and (Maskit 1988). The Swiss mathematicians (de la Harpe 1990) and Haefliger have provided an introductory account, taking geometric group theory as their starting point.[35]

Conformal mapping of Schwarz triangles

In this section Schwarz's explicit conformal mapping from the unit disc or the upper half plane to the interior of a Schwarz triangle will be constructed as the ratio of solutions of a hypergeometric ordinary differential equation, following (Carathéodory 1954), (Nehari 1975) and (Hille 1976). The classical account of (Ince 1944) has an account of the monodromy of second order complex order differential equations with regular singular points. The limiting case of ideal triangles, the Farey series and the modular lambda function is explained in (Ahlfors 1966), (Chandrasekharan 1985), (Mumford Series) and (Hardy Wright).

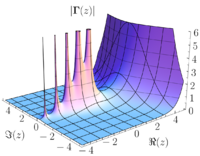

The Schwarz triangle function or Schwarz s-function is a function that conformally maps the upper half plane to a triangle in the upper half plane having lines or circular arcs for edges. Let πα, πβ, and πγ be the interior angles at the vertices of the triangle. If any of α, β, and γ are greater than zero, then the Schwarz triangle function can be given in terms of hypergeometric functions as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ s(z) = z^{\alpha} \frac{_2 F_1 \left(a', b'; c'; z\right)}{_2 F_1 \left(a, b; c; z\right)} }[/math]

where a = (1−α−β−γ)/2, b = (1−α+β−γ)/2, c = 1−α, a′ = a − c + 1 = (1+α−β−γ)/2, b′ = b − c + 1 = (1+α+β−γ)/2, and c′ = 2 − c = 1 + α. This mapping has singular points at z = 0, 1, and ∞, corresponding to the vertices of the triangle with angles πα, πγ, and πβ respectively. At these singular points,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{aligned} s(0) &= 0, \\[5mu] s(1) &= \frac {\Gamma(1-a')\Gamma(1-b')\Gamma(c')} {\Gamma(1-a)\Gamma(1-b)\Gamma(c)},\,\text{and} \\[5mu] s(\infty) &= \exp\left(i \pi \alpha \right)\frac {\Gamma(1-a')\Gamma(b)\Gamma(c')} {\Gamma(1-a)\Gamma(b')\Gamma(c)}. \end{aligned} }[/math]

This formula can be derived using the Schwarzian derivative.

This function can be used to map the upper half-plane to a spherical triangle on the Riemann sphere if α + β + γ > 1, or a hyperbolic triangle on the Poincaré disk if α + β + γ < 1. When α + β + γ = 1, then the triangle is a Euclidean triangle with straight edges: a = 0, [math]\displaystyle{ _2 F_1 \left(a, b; c; z\right) = 1 }[/math], and the formula reduces to that given by the Schwarz–Christoffel transformation. In the special case of ideal triangles, where all the angles are zero, the triangle function yields the modular lambda function.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Poincaré metric on the disk corresponds to the restriction of the G-invariant pseudo-Riemannian metric dx2 – dw2 to the hyperboloid.

- ↑ The condition on tangent vectors x, y is given by det (x,y) ≥ 0 and is preserved because the determinant of the Jacobian is positive.

- ↑ As in the case of P2, if an angle of Δ equals π/3, vertices where the interior angle is π stay marked as vertices and colinear edges are not coallesced.

References

- ↑ See:

- ↑ Note that the Killing form B(X,Y) = Tr[math]\displaystyle{ {}_{\mathfrak g} }[/math] ad X ad Y = 4 Tr XY.Helgason 1978

- ↑ Iversen 1992

- ↑ Magnus 1974

- ↑ Ratcliffe 2019, pp. 52–56

- ↑ Magnus 1974, p. 37

- ↑ Carathéodory 1954, pp. 177–181

- ↑ Carathéodory 1954, pp. 178−180

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Carathéodory 1954, pp. 181–182

- ↑ See:

- ↑ See:

- Threlfall 1932, pp. 20–22, Figure 9

- Weber 2005

- ↑ Carathéodory 1954, p. 183

- ↑ Carathéodory 1954, p. 184

- ↑ See:

- Evans 1973, pp. 108−109

- Berndt & Knopp 2008, pp. 16−17

- ↑ Graham, Knuth & Patashnik 1994, p. 118

- ↑ Series 2015

- ↑ See:

- ↑ Siegel 1971, pp. 85–87

- ↑ For proofs of Poincaré's polygon theorem, see

- Maskit 1971

- de Rham 1971

- Beardon 1983, pp. 242–249

- Iversen 1992, pp. 200–208

- Epstein & Petronio 1994

- Berger 2010, pp. 616–617

- ↑ Beardon 1984, pp. 106–107, 110–111

- ↑ See:

- ↑ See:

- ↑ Lehner 1964

- ↑ Maskit 1971

- ↑ See:

- ↑ Heckman 2017.

- ↑ Howlett 1996

- ↑ In the limit as x tends to 0, (στ)m(es) = (2m+1)es + 2met and τ(στ)m(es) = (2m+1)es + (2m+2)et.

- ↑ See:

- ↑ Here Γ is regarded as acting on V through the geometric representation.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 See:

- ↑ See:

- ↑ See:

- ↑ SL±(2,R) is the subgroup of GL(2,R) with determinant ±1.

- ↑ See:

- Milnor 1975

- Beardon 1983, pp. 242–249

- Iversen 1992, pp. 200–208

- Bridson & Haefliger 1999

- Berger 2010, pp. 616–617

- ↑ Lee, Laurence (1976). Conformal Projections based on Elliptic Functions. Cartographica Monographs. 16. University of Toronto Press. https://archive.org/details/conformalproject0000leel. Chapters also published in The Canadian Cartographer. 13 (1). 1976.

Sources

- Abramenko, Peter; Brown, Kenneth S. (2007). Buildings: Theory and Applications. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 248. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-78834-0.

- Ahlfors, Lars V. (1966), Complex Analysis (2nd ed.), McGraw Hill

- Beardon, Alan F. (1983), "Poincaré's Theorem", The Geometry of Discrete Groups, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 91, Springer, pp. 242–252, ISBN 0-387-90788-2

- Beardon, Alan F. (1984), "A primer on Riemann surfaces", London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series (Cambridge University Press) 78, ISBN 0521271045, https://archive.org/details/primeronriemanns0000bear

- Berger, Marcel (2010), Geometry revealed. A Jacob's ladder to modern higher geometry, Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-70996-1

- Berndt, Bruce C.; Knopp, Marvin I. (2008), Hecke's theory of modular forms and Dirichlet series, Monographs in Number Theory, 5, World Scientific, ISBN 978-981-270-635-5

- Björner, Anders; Brenti, Francesco (2005). Combinatorics of Coxeter groups. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 231. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3540-442387.

- Borel, Armand (1997). "I. Basic material on SL2(R), discrete subgroups, and the upper half-plane". Automorphic forms on SL2(R). Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics. 130. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-58049-8. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/automorphic-forms-on-sl2-r/20CDEAD276B61040B2B9013A21ACC145.

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1968). "Chapitre IV : Groupes de Coxeter et systèmes de Tits • Chapitre V : Groupes engendrés par des réflexions". Groupes et algèbres de Lie. Éléments de mathématique. Paris: Hermann. pp. 1–56, 57–141. Reprinted by Masson in 1981 as ISBN 2-225-76076-4.

- Bridson, Martin R.; Haefliger, André (1999). "I. Basic material on SL2(R), discrete subgroups, and the upper half-plane". Metric spaces of non-positive curvature. Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften. 319. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-64324-9. https://www.math.bgu.ac.il/~barakw/rigidity/bh.pdf.

- Brown, Kenneth S. (1989). Buildings. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96876-8.

- Busemann, Herbert (1955), The geometry of geodesics, Academic Press

- Carathéodory, Constantin (1954), Theory of functions of a complex variable, 2, Chelsea

- Chandrasekharan, K. (1985), Elliptic functions, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften, 281, Springer, ISBN 3-540-15295-4

- Davis, Michael W. (2008), "Appendix D. The Geometric Representation", The geometry and topology of Coxeter groups, London Mathematical Society Monographs, 32, Princeton University Press, pp. 439–447, ISBN 978-0-691-13138-2

- de la Harpe, Pierre (1991). "An invitation to Coxeter groups". Group theory from a geometrical viewpoint (Trieste, 1990). World Scientific. pp. 193–253.

- Deodhar, Vinay V. (1982). "On the root system of a Coxeter group". Comm. Algebra 10: 611–630. doi:10.1080/00927878208822738.

- Deodhar, Vinay V. (1986). "Some characterizations of Coxeter groups". Enseign. Math. 32: 111–120. https://www.e-periodica.ch/cntmng?var=true&pid=ens-001:1986:32::54.

- de Rham, G. (1971). "Sur les polygones générateurs de groupes fuchsiens". Enseign. Math. 17: 49–61. https://www.e-periodica.ch/cntmng?pid=ens-001%3A1971%3A17%3A%3A33.

- Ellis, Graham (2019). "Triangle groups". An Invitation to Computational Homotopy. Oxford University Press. pp. 441–444. ISBN 978-0-19-883298-0.

- Epstein, David B. A.; Petronio, Carlo (1994). "An exposition of Poincaré's polyhedron theorem". Enseign. Math. 40: 113–170. https://www.e-periodica.ch/cntmng?pid=ens-001%3A1994%3A40%3A%3A49.

- Evans, Ronald (1973), "A fundamental region for Hecke's modular group", Journal of Number Theory 5 (2): 108–115, doi:10.1016/0022-314x(73)90063-2

- Fricke, Robert; Klein, Felix (1897) (in de), Vorlesungen über die Theorie der automorphen Functionen. Erster Band; Die gruppentheoretischen Grundlagen, B. G. Teubner, ISBN 978-1-4297-0551-6, https://archive.org/details/vorlesungenber01fricuoft

- Graham, Ronald L.; Knuth, Donald E.; Patashnik, Oren (1994), Concrete mathematics (2nd ed.), Addison-Wesley, pp. 116–118, ISBN 0-201-55802-5

- Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (2008), An introduction to the theory of numbers (6th ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-921986-5

- Hatcher, Allen (2013). "1. The Farey Diagram". Topology of Numbers. Cornell University. https://pi.math.cornell.edu/~hatcher/TN/TNbook.pdf. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- Hecke, E. (1935), "Über die Bestimmung Dirichletscher Reihen durch ihre Funktionalgleichung" (in de), Mathematische Annalen 112: 664–699, doi:10.1007/bf01565437

- Heckman, Gert J. (2018). "Coxeter Groups". Radboud University Nijmegen. https://www.math.ru.nl/~heckman/CoxeterGroups.pdf.

- Helgason, Sigurdur (1978), Differential geometry, Lie groups and symmetric spaces, Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-338460-5

- Helgason, Sigurdur (2000), Groups and geometric analysis. Integral geometry, invariant differential operators, and spherical functions, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, 83, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-2673-5

- Hille, Einar (1976), Ordinary differential equations in the complex domain, Wiley-Interscience

- Hiller, Howard (1982). Geometry of Coxeter groups. Research Notes in Mathematics. 54. Pitman. ISBN 0-273-08517-4.

- Howlett, Robert (1996). "Introduction to Coxeter Groups". Australian National University Geometric Group Theory Workshop. Sydney. https://www.maths.usyd.edu.au/u/ResearchReports/Algebra/How/1997-6.html.

- Humphreys, James E. (1990). Reflection groups and Coxeter groups. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. 29. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37510-X.

- Ince, E. L. (1944), Ordinary Differential Equations, Dover

- Iversen, Birger (1992), Hyperbolic geometry, London Mathematical Society Student Texts, 25, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43508-0

- Iwahori, Nagayoshi (1966). "On discrete reflection groups on symmetric Riemannian manifolds". Proc. U.S.-Japan Seminar in Differential Geometry (Kyoto, 1965). Tokyo: Nippon Hyoronsha. pp. 57–62.

- Johnson, Norman W. (2018). Geometries and Transformations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-10340-5. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/geometries-and-transformations/94D1016D7AC64037B39440729CE815AB.

- Magnus, Wilhelm (1974), Noneuclidean tesselations and their groups, Pure and Applied Mathematics, 61, Academic Press, https://www.sciencedirect.com/bookseries/pure-and-applied-mathematics/vol/61/suppl/C

- Magnus, Wilhelm; Karrass, Abraham; Solitar, Donald (1976). Combinatorial group theory: Presentations of groups in terms of generators and relations (Second revised ed.). Dover Books.

- Maskit, Bernard (1971), "On Poincaré's theorem for fundamental polygons", Advances in Mathematics 7 (3): 219–230, doi:10.1016/s0001-8708(71)80003-8, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0001870871800038?via%3Dihub

- Maskit, Bernard (1988). "Poincaré's theorem". Kleinian groups. Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften. 287. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-17746-9.

- Maxwell, George (1982). "Sphere packings and hyperbolic reflection groups". J. Algebra 79: 78–97.

- McMullen, Curtis T. (1998), "Hausdorff dimension and conformal dynamics. III. Computation of dimension", American Journal of Mathematics 120: 691–721, doi:10.1353/ajm.1998.0031

- Matsumoto, Hideya (1964). "Générateurs et relations des groupes de Weyl généralisés". C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 258: 3419–3422. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4011c/f1029.item.

- Milnor, John (1975). "On the 3-dimensional Brieskorn manifolds M(p,q,r)". Knots, groups, and 3-manifolds (Papers dedicated to the memory of R. H. Fox). Ann. of Math. Studies. 84. Princeton University Press. pp. 175–225.

- Mumford, David; Series, Caroline; Wright, David (2015), Indra's pearls. The vision of Felix Klein, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-56474-9

- Nehari, Zeev (1975), Conformal mapping, Dover

- Ratcliffe, John G. (2019). Foundations of hyperbolic manifolds. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 149 (Third ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-31597-9.

- Schlag, Wilhelm (2014). "Uniformization". A course in complex analysis and Riemann surfaces. Graduate Studies in Mathematics. 154. American Mathematical Society. pp. 305–351. ISBN 978-0-8218-9847-5.

- Series, Caroline (2015), Continued fractions and hyperbolic geometry, Loughborough LMS Summer School, http://homepages.warwick.ac.uk/~masbb/HypGeomandCntdFractions-2.pdf, retrieved 15 February 2017

- Siegel, C. L. (1971), Topics in complex function theory, II. Automorphic functions and abelian integrals, Wiley-Interscience, pp. 85–87, ISBN 0-471-60843-2

- Steinberg, Robert (1968). Endomorphisms of linear algebraic groups. Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society. 80. American Mathematical Society. https://bookstore.ams.org/memo-1-80/9.

- Szenthe, J. (1993). "A significant property of real hyperbolic spaces". Proceedings of Symposium in Geometry (Cluj-Napoca and Tîrgu Mureş, 1992). pp. 153–161.

- Takeuchi, Kisao (1977a), "Arithmetic triangle groups", Journal of the Mathematical Society of Japan 29: 91–106, doi:10.2969/jmsj/02910091

- Takeuchi, Kisao (1977b), "Commensurability classes of arithmetic triangle groups", Journal of the Faculty of Science, The University of Tokyo, Section IA, Mathematics 24: 201–212

- Threlfall, W. (1932), "Gruppenbilder", Abhandlungen der Mathematisch-physischen Klasse der Sachsischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Hirzel) 41: 1–59, http://digital.slub-dresden.de/fileadmin/data/304910686/304910686_tif/jpegs/304910686.pdf

- Tits, Jacques (2013). "Groupes et géométries de Coxeter". Œuvres/Collected works, Volume I. Heritage of European Mathematics. Zürich: European Mathematical Society. pp. 803–817. ISBN 978-3-03719-126-2. https://www.ems-ph.org/books/book.php?proj_nr=168. This manuscript was the foundational text for the theory of Coxeter groups, used for preparing Chapter IV of Bourbaki's Groupes et Algèbres de Lie; it was first published in 2001.

- Vinberg, Ernest B. (1971). "Discrete linear groups generated by reflections". Mathematics of the USSR-Izvestiya 5: 1083–1119.

- Vinberg, Ernest B. (1985). "Hyperbolic reflection groups". Russian Mathematical Surveys (London Mathematical Society) 40: 31–75. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1070/RM1985v040n01ABEH003527/pdf.

- Vinberg, Ernest B.; Shvartsman, O. V. (1993). "Discrete groups of motions of spaces of constant curvature". Geometry II: Spaces of Constant Curvature. Encyclopaedia Math. Sci.. 29. Springer-Verlag. pp. 139–248. ISBN 3-540-52000-7.

- Weber, Matthias (2005), "Kepler's small stellated dodecahedron as a Riemann surface", Pacific Journal of Mathematics 220: 167–182, doi:10.2140/pjm.2005.220.167, http://msp.org/pjm/2005/220-1/p09.xhtml

- Wolf, Joseph A. (2011), Spaces of constant curvature (6th ed.), AMS Chelsea, ISBN 978-0-8218-5282-8

- Yoshida, Masaaki (1987). Fuchsian differential equations, with special emphasis on the Gauss-Schwarz theory. Aspects of Mathematics. E11. Friedr. Vieweg & Sohn. ISBN 3-528-08971-7.

Further reading

- Ford, Lester R. (1951), Automorphic Functions, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0821837419

- Lehner, Joseph (1964), Discontinuous groups and automorphic functions, Mathematical Surveys, 8, American Mathematical Society. (Note that Lehner has pointed out that his proof of Poincaré's polygon theorem is incomplete. He has subsequently recommended de Rham's 1971 exposition.)

- Sansone, Giovanni; Gerretsen, Johan (1969), Lectures on the theory of functions of a complex variable. II: Geometric theory, Wolters-Noordhoff

- Series, Caroline (1985), "The modular surface and continued fractions", Journal of the London Mathematical Society 31: 69–80, doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-31.1.69

- Thurston, William P. (1997), Silvio Levy, ed., Three-dimensional geometry and topology. Vol. 1., Princeton Mathematical Series, 35, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08304-5