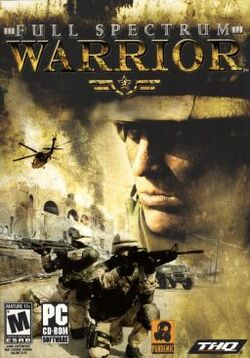

Software:Full Spectrum Warrior

| Full Spectrum Warrior | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Pandemic Studios[lower-alpha 1] |

| Publisher(s) | THQ |

| Director(s) | William Henry Stahl |

| Designer(s) | Laralyn McWilliams |

| Programmer(s) | Fredrik Persson |

| Artist(s) | Rositza Zagortcheva |

| Writer(s) | Paul Robinson |

| Composer(s) | Tobias Enhus |

| Engine | Havok |

| Platform(s) | Xbox, Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 2 |

| Release | XboxMicrosoft WindowsPlayStation 2 |

| Genre(s) | Real-time tactics |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

Full Spectrum Warrior is a real-time tactics video game developed by Pandemic Studios and published by THQ for Xbox, Microsoft Windows and PlayStation 2. A sequel titled Software:Full Spectrum Warrior: Ten Hammers was later released.

Gameplay

Full Spectrum Warrior is a squad-based game in which the player issues commands to two fireteams, Alpha and Bravo. Each fireteam has a Team Leader equipped with an M4 carbine. The Team Leaders also carry a GPS receiver, which can be used to locate mission objectives and enemy locations, and a radio for communication with headquarters. The second team member is the Automatic Rifleman, equipped with an M249 Squad Automatic Weapon, used to lay suppressive fire on the enemy and assigned to take command if the team leader is shot. The third team member is the Grenadier, equipped with an M4 with an M203 grenade launcher attachment. The last team member is the Rifleman, equipped with an M4 carbine. If a member of the team is wounded, another member of the team will carry them. Lieutenant Phillips is the team commander and the player will usually find him with the CASEVACs, which are healing and ammunition points. Each fireteam has a limited amount of fragmentation and smoke grenades, in addition to the M203 grenades. Occasionally throughout the game, there will be a third asset designated as Charlie Team, ranging from anti-armor engineers to US Army Rangers.

Throughout the game, the player does not directly control any of the fireteam members; instead, orders are given using a cursor that projects onto the environment, letting the player tell his/her soldiers to hold a position and set a specific zone to cover with fire. It is also possible to order them to lay down suppressive fire on a given zone to cover the second squad's movement, or to reduce incoming fire.

Gameplay revolves around the concept of fire and movement, with one team providing suppressive fire while the other moves. The basic gameplay mechanics remain the same for the retail version of Full Spectrum Warrior, which was released on the Xbox, PlayStation 2 and Windows platforms. The retail version places much more emphasis on aesthetics; it possesses substantially improved graphics and sound. Cut scenes and voice acting are also characteristics that distinguish the retail version from the military version.

Multiplayer

Full Spectrum Warrior includes a cooperative mode that was designed to take advantage of Microsoft's Xbox Live online gaming service through the use of voice communication. In co-op mode, two players are in command of their own fireteam and must work together to accomplish the goals of the level. Two additional missions were also available to download via Xbox Live.[2]

Plot

Background story

A dramatic wave of terrorist attacks sweeps Europe and Southeast Asia, particularly targeting US and UK interests. After months of intense searching, US intelligence has tracked the source of the attacks to the tiny fictional nation of Zekistan in Central Asia.

U.S.-led operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have forced rebels and loyalists to flee, seeking refuge in the nation of Zekistan by invitation of the nation's dictator, Mohammad Jabbour Al-Afad. His tyrannical regime houses death camps and training centers for the terrorist networks, and promotes cleansing of the ethnic Zeki population. After several failed diplomatic solutions and repeated warning by the UN, NATO votes to invade Zekistan to remove Al-Afad from power.

Pakistan grants US access through its airspace, and the invasion begins. The missing name and missing name launch aircraft to airstrike Al-Afad's air, armor, and bases across the nation. When the dust settles, infantry and armor from seven different NATO countries begin to land at southern Zekistan. Under the cover of darkness, the U.S.-led forces converge on the capital city of Zafarra.

Campaign storyline

The story starts at the MOUT (if the player chooses to play the tutorial) in Fort Benning, as fireteams Alpha and Bravo of squad Charlie 90, B Company, 159th Light Infantry goes through the training at Fort Benning, Georgia as they prepare for their deployment to Zekistan as part of the NATO Invasion force sent to invade the country. When they arrived Zekistan, their first objective is to help secure the airfield, the main airport in the city, but the route to the airport is crawling with resistance; the first few hours after they arrived, they were ambushed.

After the Airport is successfully captured, Charlie 90 is tasked with infiltrating Al-Afad's palace and eliminating him. They trek through the city and make it to the palace. While they manage to capture one of Afad's top lieutenants, Afad escapes. The members of Charlie 90 also witness one of the Joint STARS planes crashing into the city. The squad is then ordered to rescue the crew of the downed plane before they can be captured by Afad's men.

Charlie 90 secures the crash site, but the crew of the plane is taken hostage by Afad's men. Charlie 90, with the assistance of two Ranger snipers, finds and rescues the crew. Charlie 90 then track Afad down and find his SUV in an old train yard. Charlie 90 must then call in an airstrike on the SUV before it escapes. If the player orders the strike in time, U.S. gunships swoop down and destroy the SUV, eliminating Al-Afad.

Epilogue missions

Despite the death of Al-Afad, propaganda broadcasts were made by a surviving group of Al-Afad soldiers called the Black Wind Brigade, headed by one of Al-Afad's sons Al-Hamal. As a way of repaying the Army Rangers from Mike 25 a debt for saving them in a parking lot, both Alpha and Bravo team from Charlie 90 were "on loan" to them to participate in unofficial assignments. In the first mission, both teams were to mark a radio tower for an airstrike to end the propaganda broadcasts. On the second epilogue mission, both fireteams, with assistance from Staff Sergeant Hackett, were sent to a mosque to take out the Black Wind Brigade. Although Al-Hamal is killed by an airstrike during a firefight, the younger brother, Colonel Samir who was presumed to be dead assumes the role as ruler, willing to work towards democracy and stray away from his father and brother's tyrannical regime.

These missions were released as DLC for the Xbox version and are included in the PC and PS2 versions by default and unlocked from the start, but the game still goes to credits after the last "Normal" mission and the player must manually start them from the level select.

Development

In 2000, the U.S. Army's Science & Technology community was curious to learn if commercial gaming platforms could be leveraged for training. Recognizing that a high percentage of incoming recruits had grown up using entertainment software products, there was interest in determining whether software game techniques and technology could complement and enhance established training methods.

Having established a U.S. Army University Affiliated Research Center (the Institute for Creative Technologies – ICT) in 1999 for the purpose of advancing virtual simulation technology, work began in May 2000 on a project entitled C4 under ICT Creative Director James Korris with industry partners Sony Imageworks and their teammate, Pandemic Studios, represented by co-founders Josh Resnick and Andrew Goldman.

At the time, there was a great deal of interest in leveraging the stability, low cost and computational/rendering power of the new generation of game consoles, chiefly Sony's PlayStation 2 and Microsoft's Xbox, for training applications. Legal restrictions on the PlayStation (using the platform for a military purpose) combined with the default Xbox configuration "persistence" (i.e. missions recorded on the embedded hard drive for after-action review) led to the final selection of the Xbox platform for development.

A commercial release of the game was required for Xbox platform access. The team, however, quickly concluded that a viable entertainment title might differ from a valid training tool. The exaggerated physics of entertainment software titles, it was believed, could produce a negative training effect in the Soldier audience. Accordingly, the team developed two versions of the game. The Army version was accessible through a static unlock code; the entertainment version played normally.

The most radical decision in the game's development was to limit first-person actions to issuing orders and directions to virtual Fire Teams and Squad members (see Gameplay). Given the popularity of the first-person shooter genre, it was assumed that all tactical-level military gameplay necessarily involved individual combat action. The application defied conventional wisdom, winning both awards and commercial acceptance. The game's working title evolved to C-Force (2001) and ultimately Full Spectrum Warrior (2003).

As work progressed on Full Spectrum Warrior, ICT developed another real-time tactical decision-making game with Quicksilver Software entitled Full Spectrum Command for the US Army's Infantry Captains Career Course, with the first-person perspective of a Company Commander. As the application was designed to play on a desktop PC (unlike the Xbox), no commercial release was necessary. Full Spectrum Command gave rise to a sequel developed for the US Army and Singapore Armed Forces (version 1.5). A related ICT/Quicksilver title, Full Spectrum Leader, simulates the first person perspective of a Platoon Leader.

Full Spectrum Warrior relates to the Army's program of training soldiers to be flexible and adaptable to a broad range of operational scenarios.

The game's budget was $5 million.[3]

Reception

| Reception | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

At the Game Critics Awards of E3 2003, Full Spectrum Warrior was awarded "Best Original Game" and "Best Simulation Game". The staff of X-Play nominated Full Spectrum Warrior for their 2004 "Best Strategy Game" award,[30] which ultimately went to Software:Rome: Total War.[31] It was also a runner-up for Computer Games Magazine's 2004 "Best Interface" award,[32] and for GameSpot's annual "Most Innovative Game" prize.[33] During the 8th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards, the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences nominated Full Spectrum Warrior for "Console Action/Adventure Game of the Year" and "Computer Action/Adventure Game of the Year".[34]

The Xbox and PC versions received "favorable" reviews, while the PlayStation 2 version received "average" reviews according to video game review aggregator Metacritic.[29][27][28] According to the NPD Group, Full Spectrum Warrior sold roughly 190,000 units on the Xbox by the end of its debut month. Analyst Michael Pachter described this as a commercial success.[35]

The game sold nearly 1 million copies for Xbox and PC.[3]

Full Spectrum Warrior became the subject of some controversy shortly after it was released. The two primary complaints aired were that the United States Army was not using their training version of the game because it was not "realistic enough".[36] Secondly, the United States Army had been short-changed.[37] There was some discussion in the press regarding whether the government had either wasted money on the project, or if they had been taken advantage of by Pandemic Studios, and Sony Pictures Imageworks, their partner on the project.

Notes

- ↑ Ported to PlayStation 2 by Mass Media Games.

References

- ↑ Adams, David (March 22, 2005). "Full Spectrum Warrior Deployed" (in en). https://www.ign.com/articles/2005/03/22/full-spectrum-warrior-deployed.

- ↑ Adams, David (2004-10-05). "Full Spectrum Warrior Gets Fuller" (in en). https://www.ign.com/articles/2004/10/05/full-spectrum-warrior-gets-fuller.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Army". February 20, 2005. p. 12. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/96545933/tampa-bay-times/. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ↑ Edge staff (July 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior (Xbox)". Edge (138): 98. http://gamesradar.msn.co.uk/reviews/default.asp?pagetypeid=2&articleid=30716&subsectionid=1606. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ↑ EGM staff (June 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior (Xbox)". Electronic Gaming Monthly (179). http://www.egmmag.com/article2/0,2053,1606403,00.asp. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ↑ Reed, Kristan (October 4, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior (PC)". http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/r_fsw_pc.

- ↑ Bramwell, Tom (July 2, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior (Xbox)". http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/r_fullspectrumwarrior_x.

- ↑ Kato, Matthew (July 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior (Xbox)". Game Informer (135): 119. http://www.gameinformer.com/Games/Review/200407/R04.0719.1620.45333.htm. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ↑ Four-Eyed Dragon (June 1, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior Review for Xbox on GamePro.com". GamePro. http://www.gamepro.com/microsoft/xbox/games/reviews/35832.shtml. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ↑ Sanders, Shawn (June 16, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior Review (Xbox)". Game Revolution. http://www.gamerevolution.com/review/full-spectrum-warrior.

- ↑ Kasavin, Greg (September 22, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior Review (PC)". http://www.gamespot.com/reviews/full-spectrum-warrior-review/1900-6108173/.

- ↑ Kasavin, Greg (March 24, 2005). "Full Spectrum Warrior Review (PS2)". http://www.gamespot.com/reviews/full-spectrum-warrior-review/1900-6121041/.

- ↑ Kasavin, Greg (June 2, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior Review (Xbox)". http://www.gamespot.com/reviews/full-spectrum-warrior-review/1900-6099719/.

- ↑ Lopez, Miguel (September 23, 2004). "GameSpy: Full Spectrum Warrior (PC)". GameSpy. http://pc.gamespy.com/pc/full-spectrum-warrior/550641p1.html.

- ↑ Lopez, Miguel (June 2, 2004). "GameSpy: Full Spectrum Warrior (Xbox)". GameSpy. http://xbox.gamespy.com/xbox/full-spectrum-warrior/520711p1.html.

- ↑ Raymond, Justin (October 11, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior - PC - Review". GameZone. http://www.gamezone.com/reviews/full_spectrum_warrior_pc_review.

- ↑ Bedigian, Louis (April 10, 2005). "Full Spectrum Warrior - PS2 - Review". GameZone. http://www.gamezone.com/reviews/full_spectrum_warrior_ps2_review.

- ↑ Bedigian, Louis (June 12, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior - XB - Review". GameZone. http://www.gamezone.com/reviews/full_spectrum_warrior_xb_review.

- ↑ Adams, Dan (September 24, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior Review (PC)". https://www.ign.com/articles/2004/09/25/full-spectrum-warrior-review.

- ↑ Sulic, Ivan (March 22, 2005). "Full Spectrum Warrior (PS2)". https://www.ign.com/articles/2005/03/23/full-spectrum-warrior-2.

- ↑ Perry, Douglass C. (May 31, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior (Xbox)". https://www.ign.com/articles/2004/06/01/full-spectrum-warrior-6.

- ↑ "Full Spectrum Warrior". Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine. June 2005. http://www.1up.com/reviews/full-spectrum-warrior. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ↑ McCaffrey, Ryan (August 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior". Official Xbox Magazine (34): 74–75.

- ↑ "Full Spectrum Warrior". PC Gamer: 70. December 2004.

- ↑ Walk, Gary Eng (June 18, 2004). "Full Spectrum Warrior (Xbox)". Entertainment Weekly (770): L2T 20. https://www.ew.com/article/2004/06/18/full-spectrum-warrior. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ↑ Herold, Charles (August 5, 2004). "GAME THEORY: O.K., Private, Give Me 50, Then Play This Video Game". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/08/05/technology/game-theory-ok-private-give-me-50-then-play-this-video-game.html.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Full Spectrum Warrior for PC Reviews". https://www.metacritic.com/game/full-spectrum-warrior/critic-reviews/?platform=pc.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Full Spectrum Warrior for PlayStation 2 Reviews". https://www.metacritic.com/game/full-spectrum-warrior/critic-reviews/?platform=playstation-2.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Full Spectrum Warrior for Xbox Reviews". https://www.metacritic.com/game/full-spectrum-warrior/critic-reviews/?platform=xbox.

- ↑ X-Play Staff (January 18, 2005). "X-Play's Best of 2004 Nominees". X-Play. http://www.g4tv.com:80/xplay/features/50787/XPlays_Best_of_2004_Nominees.html.

- ↑ X-Play Staff (January 27, 2005). "X-Play's Best of 2004 Winners Announced!". X-Play. http://www.g4tv.com:80/xplay/features/50882/XPlays_Best_of_2004_Winners_Announced.html.

- ↑ Staff (March 2005). "The Best of 2004; The 14th Annual Computer Games Awards". Computer Games Magazine (172): 48–56.

- ↑ "Best and Worst of 2004". GameSpot. January 5, 2005. http://www.gamespot.com/gamespot/features/all/bestof2004/.

- ↑ "D.I.C.E. Awards By Video Game Details Full Spectrum Warrior". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. https://www.interactive.org/games/video_game_details.asp?idAward=2005&idGame=222.

- ↑ Feldman, Curt (July 20, 2004). "NPD: June game sales up 12 percent". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com:80/news/2004/07/20/news_6103066.html.

- ↑ "Playing to win". The Economist. December 4–10, 2004. https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2004/12/04/playing-to-win.

- ↑ Adair, Bill (February 20, 2005). "Did the Army get Out-Gamed?". St. Petersburg Times. http://www.sptimes.com/2005/02/20/Worldandnation/Did_the_Army_get_out_.shtml.

External links

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

|